Our Woman in Havana

Even in hostile environments, FSOs effectively represent U.S. interests through open communication. Here is one case study.

BY VICKI J. HUDDLESTON

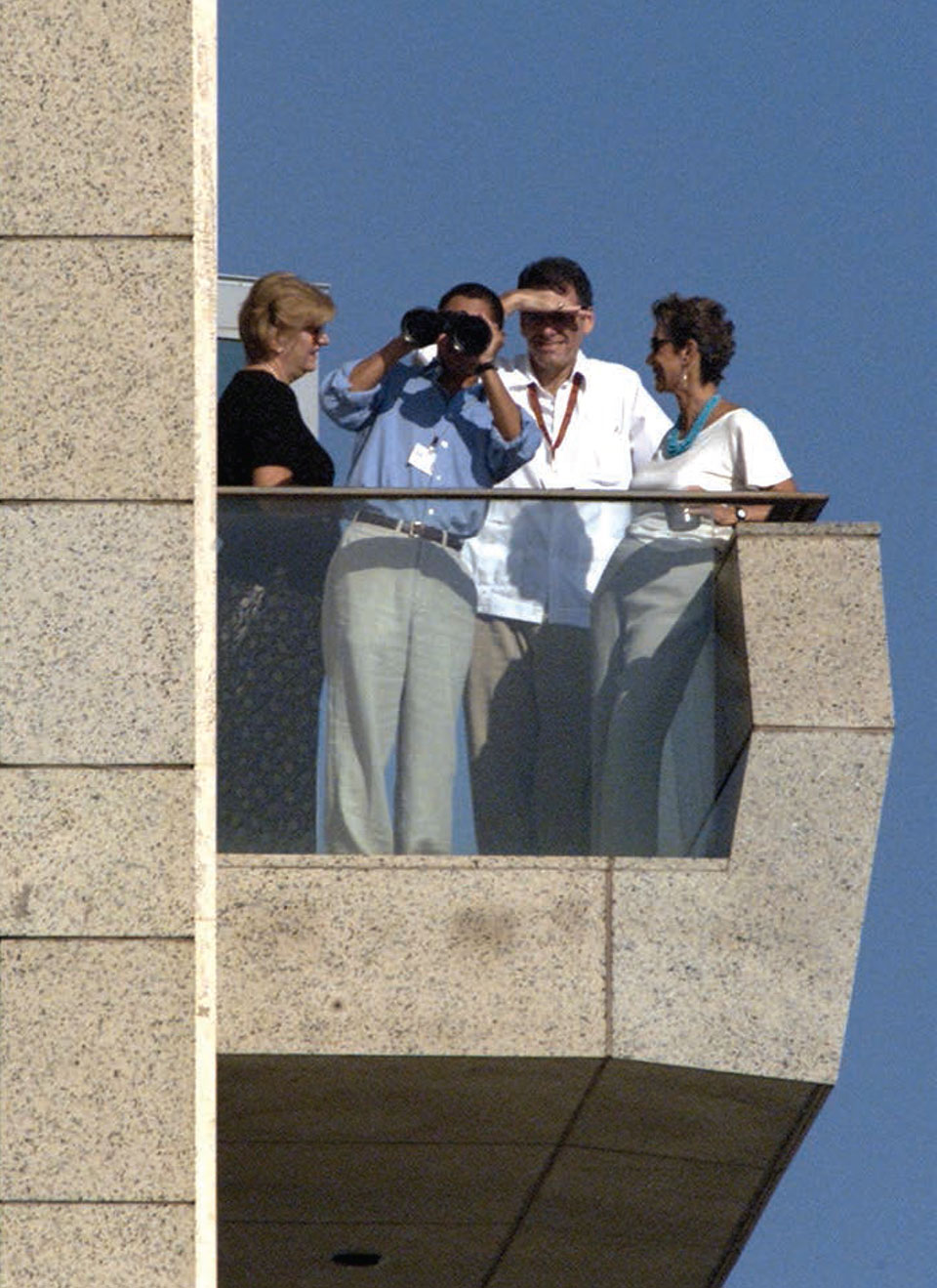

Vicki Huddleston, at right, and other U.S. diplomats on a balcony of the U.S. Interests Section that overlooks the “Jose Marti Open Court,”a huge outdoor amphitheater used for political rallies, five floors below. This photo was taken on June 29, 2001, when 30,000 Cubans led by President Fidel Castro rallied to protest the jailing of five Cuban agents in Florida on spying-related charges.

Reuters / Rafael Perez / Hulton Archive

It would be an understatement to say that my three years (1999-2002) as principal officer of the U.S. Interests Section in Havana were full of ups and downs. At one point, Fidel Castro threatened to designate me persona non grata for distributing AM/FM/shortwave radios. Yet some years later Ricardo Alarcon, then president of the Cuban National Assembly, told a forum of American, Canadian and Cuban scholars that I had done a good job there.

And while I became the darling of Miami’s Cuban-American community for strongly defending the country’s internal human rights groups, they sharply criticized me for my role in resolving the Elian Gonzalez saga.

What my various critics either didn’t see, or didn’t accept, was that I consistently sought to cultivate a professional relationship of trust and respect throughout my time in Havana, even when our bilateral relations were in conflict. Admittedly, it helped that I liked everything about Cuba: the people, the place and the officials with whom I dealt. But even if I hadn’t enjoyed my time there, I had no doubt that my job was to represent the interests of my government through open, continuous communication and compromise.

Toward that end, I accepted the Cuban government as legitimate. After all, it is a voting member of the United Nations. And more governments have diplomatic representatives resident in Havana, a leader of the developing world, than in Mexico City or Brasilia.

I also made it a rule never to personally insult or denigrate Fidel Castro. After all, if I incurred his enmity I would no longer be able to effectively represent my country.

I was honored to be the eighth principal officer sent to Havana after President Jimmy Carter reopened diplomatic relations in 1977, and both governments opened interests sections in their former embassies, which had been closed since 1961.

President Bill Clinton and his advisers selected me to lead the U.S. Interests Section in 1999 with the expectation that my years of experience working on Cuba equipped me to improve relations. I had been deputy director and subsequently director of the Office of Cuban Affairs at the State Department from 1989 to 1993. I had also been an ambassador to Madagascar, so we hoped that title might indicate that we were serious about change. We also knew that Fidel preferred to deal with women.

But just two months after my arrival in Havana in September 1999, the miraculous rescue of a 6-year-old child in the Florida Straits put our countries on a collision course.

Soon after my arrival in Havana, the miraculous rescue of a 6-year-old child in the Florida Straits put our countries on a collision course.

The Elian Gonzalez Saga

Fleeing Cuba in an unseaworthy boat, Elian Gonzalez’s mother had tied him to an inner tube before losing her own life. Days later, he was rescued by a fisherman, taken to a Miami hospital by the Coast Guard, and then turned over to relatives who, despite his father’s pleas, refused to return him to his family in Cardenas, Cuba.

Over the next six months, the Elian saga dominated U.S.-Cuban relations, as Fidel and Raul Castro led “million man” marches demanding Elian’s immediate return. When a State Department spokesman said that the United States would hold Cuba responsible for the safety of its personnel in Havana, Fidel sent schoolchildren arrayed in their Pioneer uniforms to “protect” us. Hand in hand they surrounded the Interests Section, making the United States look like a helpless giant.

Next, in just three months Castro turned the overgrown and neglected area in front of the chancery into a giant outdoor amphitheater: the Jose Marti Tribuna Abierta (open court), built to condemn the United States for allegedly “stealing Cuba’s child.”

Ironically, during the construction one of our Cuban guards found buried in the rubble a bronze plaque commemorating the dedication of the “Fourth of July Park.” We hung it on the outside wall of USINT facing the Tribuna Abierta, where a once-close friendship had dissolved into bitterness over the embargo, migration policy and Guantanamo Base.

For their part, Cuban-Americans were equally adamant that right was on their side. Not only was Elian Gonzalez entitled to remain in America; Washington had no right to send him back.

In their eyes, the boy couldn’t possibly be returned to that “prison island,” even if it was into the arms of a loving father, for he was an embodiment of themselves, their dreams and hopes. Even worse, his repatriation would be a victory for their nemesis, Fidel Castro. But in the end, Elian did return, giving Cubans a younger and more modern hero than bearded revolutionaries of the past and present.

A Peaceful Resolution Pays Dividends

Meanwhile, behind the scenes my staff and I worked quietly with Ricardo Alarcon and the head of the North American division of the Cuban Foreign Ministry, Dagoberto Rodriguez. With the White House’s blessing, we agreed on a strategy that would return Elian to Cuba. USINT personnel would visit his father, Juan Miguel Gonzalez, to determine whether he had a strong bond with his son. If so, then Washington would uphold in state and federal courts the father’s right to be reunited with Elian.

The Cubans remained suspicious and uneasy. Elian and the dysfunctional relatives with whom he was living were constantly in the public eye. As some members of Congress considered introducing legislation to make the boy an American citizen, Elian’s rather unpleasant grandmothers visited him in Miami. Throughout a process that took much longer than either capital anticipated, my job was to keep relations on an even keel.

When Elian finally returned to Cuba in June 2000, Fidel Castro and his seldom-seen spouse, Dalia, joined Juan Miguel Gonzalez and his family in the front row of the Tribuna Abierta. They were there with most of the Cuban hierarchy to watch schoolchildren stage a production welcoming the boy home.

From our office balcony, my staff and I also enjoyed the spectacle, but no one acknowledged our presence five stories above. We were such a close and trusted enemy that Cuba’s leadership sat below without ever imagining that we might pose a danger.

Fidel Castro was not pleased with our outreach, to put it mildly; he hated my little radios.

In fact, our two countries are not real enemies, though it serves the interests of some people to pretend we are. The Cuban-American community continues to seek retribution for Castro’s takeover more than a half-century ago, while Havana uses U.S. sanctions as a scapegoat for its multitude of homegrown ills.

The professional relationship that we fostered with the Cubans during the Elian saga built good will. It may even have contributed to Fidel Castro’s decision to cooperate with the U.S. military at Camp X-Ray at Guantanamo Base.

In early 2002, my bosses at State told me that we would begin imprisoning illegal combatants from the war in Afghanistan at Guantanamo Bay. I immediately informed Alarcon, who complained that it was clear that his government had no say in the matter. I replied that while that might be true, public objections would make many people think that Cubans were on the side of the terrorists who had perpetrated the tragic 9/11 attacks.

Castro bought the argument. He not only refrained from criticizing our actions, but ordered the Cuban military to help us ensure that the base was secure from outside attack. They even turned over a portion of Cuban airspace to U.S. air controllers.

Little Radios, Big Symbols

In late 2000 my staff and I created an outreach program designed to empower the Cuban people and, particularly, the dissidents. We distributed hundreds of thousands of books and radios all over the island to libraries run by the Catholic Church, the Masons and independent journalists. We also invited dissidents into our homes so they could meet with other activists, as well as visiting members of Congress and journalists.

The most important visitor was former President Jimmy Carter, who courageously endorsed Osvaldo Paya’s Project Varela (advocating democratic political reforms) in a speech at the University of Havana. Fidel Castro and the Cuban hierarchy sitting in the front row were dismayed when he recommended that they allow a vote to change the constitution, as Project Varela called for.

Since so many Cubans had heard Carter’s words on radio and television, Fidel chose to counter them by organizing his own nationwide petition. He succeeded in making the Cuban Constitution immutable by ordering block committees to go door to door collecting signatures of every adult in the country. But we didn’t have to be successful; we simply had to do what we could to support the activists and give them hope for change.

Fidel Castro was not pleased with our outreach, to put it mildly; he hated my little radios. But Cubans loved them because for the first time in decades, they had access to information not controlled by the state. They now had a choice between tuning into Fidel’s speeches, or the BBC or Voice of America. Dissidents could also listen to Radio Marti simply by taking the portable radios to a location where jamming was ineffective.

Castro demanded that we cease distributing the radios. When I refused, he retaliated by gathering some 20,000 people together at Miramar—a large public housing complex on the other side of Havana Bay—to condemn our actions. Undaunted, I attended the rally alongside the chief of the consular section and our human rights officer. Castro was so shocked that for the first time ever, he did not speak at the rally even though he was on stage.

When I returned to the office after the event, which was carried on Cuban radio and TV, prominent human rights activist Felix Bonne was waiting for me. Bonne had been a professor of engineering at the University of Havana before being fired for views incompatible with those of the Communist Party hierarchy. He was then sent to jail for writing and publishing, along with three other well-known, respected Cuban dissidents, a book titled La Patria Es de Todos (The Country Is for Everyone).

Felix began with praise and then delivered a warning. He told me that though I seemed to him like a colonel leading her troops, I had better be sure I had chosen a battle I could win. He reminded me that I must protect our bilateral relationship.

I knew that he was right. If the Cuban government closed USINT, as Fidel had threatened, we could no longer speak on behalf of the dissidents. Nor would we be able to effectively advocate for them if they were abused or jailed. So, to defuse the conflict, I lowered my profile. But we continued distributing our “little radios”—just more quietly.

Castro was so shocked I attended the rally that, for the first time ever, he did not speak even though he was on stage.

Bilateral Relations Today

My team and I successfully balanced doing things the Cuban government disliked—handing out radios and books around the country, and supporting human rights activists—with maintaining a professional and productive relationship that gained Fidel Castro’s cooperation with our military at Guantanamo Base. I am not sure how much longer we could have maintained this delicate balance. But one thing is certain: it did not last long after my departure.

Although President George W. Bush had initially maintained and even expanded the Clinton measures that allowed people-to-people travel, the policy had already begun to change as Jeb Bush sought the support of the Cuban-American community for a second term as governor of Florida. My successor as principal officer was encouraged to publicly confront the Cuban government, even as the administration began to reduce travel licenses to Cuba. Hostile rhetoric from both sides increased.

The distribution of radios and books was significantly reduced when the Cuban government curtailed travel by U.S. diplomats to Havana, in response to our government’s decision to restrict Cuban diplomats to within 25 miles of Washington, D.C. Then, as tensions heightened, the Cuban government jailed 75 committed human rights activists, independent journalists and trade unionist.

Bilateral relations did not begin to thaw until after the Obama administration took office in 2009, when Havana began releasing some of the human rights activists who had been detained. Currently, our relationship is constructive, and travel to Cuba by Americans exceeds the levels reached during the Clinton administration. But we have never regained the momentum that led to the Cuban Spring of 2002.

An Amazing Job

I consider myself very fortunate to have been selected to manage our relations with Cuba in Havana 15 years ago. While leading the interests section was an adventure, and great fun, it was also frustrating and infuriating. Yet the assignment afforded me opportunities to make difficult decisions, and to make a real difference.

It also taught me—and perhaps some Cubans and Cuban-Americans, as well—that despite our fundamentally different points of view on many topics, there was no reason we could not work together to resolve some of our differences.

All in all, it was an amazing job—the best of my Foreign Service career.