George H.W. Bush: Diplomats Remember

As the January-February issue went to press, President George H.W. Bush passed away. Throughout his life—as a member of Congress, ambassador to the United Nations and U.S. representative to the People’s Republic of China, and as CIA director, vice president and president, and well into his 90s—he crossed paths with and left an impression on so many in the diplomatic community.

Here is a sampling of Foreign Service recollections, including our own.

–The Editors

A Man of Character

BY PARKER W. BORG

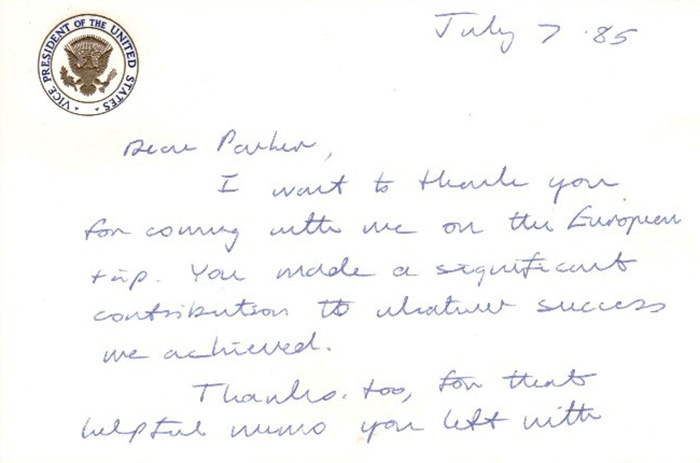

A handwritten note from Vice President George H.W. Bush to Parker Borg.

Courtesy of Parker Borg

I was late—as I still often am. I needed to catch a plane at Andrews Air Force Base at 6:30 a.m., but wasn’t quite sure how to get to the terminal. Anna couldn’t believe I could get both the timing and the directions so confused. In my defense, I had been working hard the past few days, and the trip was a last-minute add-on to my schedule. Still, no excuse. I made it planeside about 10 minutes late. The aircraft was still on the ground, but took off as soon as I boarded. According to the protocol for such flights, the plane leaves when the head of the delegation arrives and has been seated, not when a minor staff member (me) shows up. After all, this was Air Force II (Air Force I being the president’s plane).

It was June 1985. I was then working on counterterrorism at the State Department. On June 14, Palestinian hijackers had seized an American aircraft (TWA Flight 847) on its leg between Athens and Rome. The incident continued for the next 17 days as the hijackers shuttled the plane among Mediterranean capitals to avoid capture before landing it in Beirut. Over those days the hijackers had killed one U.S. serviceman, beat up some travelers, attempted to identify Jews on the plane and released a few passengers, all females. In Beirut, they still held 40 male passengers and the crew. From Day One, we were working daily 12- to 14-hour shifts in the State Department’s Task Force area, attempting to track the movements of the plane and the status of the passengers, while working with the Special Operations Command of the Defense Department to find ways to bring the hijacking to an end. The work was stressful and the conditions chaotic. Each day we were more exhausted.

Vice President George H.W. Bush had previously scheduled an official visit to seven European capitals for the last week of June. Terrorism was not on the agenda, but this endless hijacking suddenly added a new dimension to his trip. Whether desired or not, counterterrorism would be a topic at each stop. A few days before the June 23 departure date, the vice president’s office had asked the State Department for a terrorism expert to join the delegation. Since my boss, Robert Oakley, was the head of the task force, he couldn’t leave. He designated me, as his deputy, to join the vice president. And so at the last minute I was rushing to catch Air Force II to Europe.

The trip got off to a rough start, but there was never a harsh word from the vice president or his staff about my late arrival. Now part of the delegation, I was included in all the meetings with foreign leaders, attended the audience with Pope John Paul II and had a seat at the table for meals at the PM’s office at 10 Downing Street in London and the Élysée Palace in Paris. When asked, I explained U.S. policy and actions, stressing the importance of international cooperation; but I wasn’t asked for my thoughts very often. About midway through the trip, the crisis ended and some 40 hostages were permitted to return to the United States. When the Air Force plane carrying them back touched down at Rheine Main Air base for debriefing and medical exams, Vice President Bush was present. We returned to the States in the early hours of July 4, having been away for nearly two weeks.

At some point during the trip, probably feeling the pressure to show the White House was engaged on terrorism, President Ronald Reagan issued a statement saying he had asked Vice President Bush to chair a new interagency group to review counterterrorism policy. On the last leg of the trip, I put together my thoughts on the key interagency counterterrorism questions and gave them to Don Gregg, Bush’s assistant for national security affairs.

Three days after we landed I received a handwritten note from Vice President Bush, thanking me for my support and for the memo I’d presented about the work of his new task force. Whether he ever looked at my memo, I’ll never know; but he remembered it and made a point of thanking me for it.

Bush was famous for his notes to leaders and people who had been helpful to him. It was his way of developing personal relationships with leaders around the world, but there was no particular reason for him to send me a message. Such was the graciousness of George H. W. Bush.

‘Ah, Yes, I Know Ambassador Borg’

I had first met George Bush in late 1972, when he was U.S. ambassador to the United Nations and I was working as special assistant to the Director General. As ambassador, he was concerned that diplomats assigned to work at the United Nations couldn’t afford the rent near the U.S. mission in midtown Manhattan. Unlike foreign postings where supplemental allowances helped cover costs for expensive places like London or Tokyo, there were no such allowances for diplomats living in expensive American cities.

Bush thought this was wrong and detrimental to U.S. goals. He wanted to fix it. To my knowledge, no previous U.S. ambassador in New York had raised this issue. After our delegation met with him to hear his concerns, we went back to Washington and arranged that all U.S. diplomats assigned to New York would receive new cost-of-living allowances. That was yet another example of Bush’s graciousness.

I had several other occasions to meet with him, most memorably when Terry Waite, the Anglican priest who was trying to broker the release of hostages in Lebanon, returned from one of his first trips to the region and briefed the White House on his observations.

I crossed paths with him again in Hawaii on Dec. 7, 1991, at the ceremony commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Having been appointed by President Bush as ambassador-designate to Myanmar/Burma, I was attending the East Asia Chief of Mission Conference scheduled for that weekend. In a session with the president, each of us made a brief statement. Mine was especially brief because the Senate was still holding my nomination in limbo. When he came around to shake each of our hands, President Bush said, “Ah, yes, I know Ambassador Borg.”

Friends and former adversaries have written much about George H. W. Bush as president—a man committed to service to his nation and a courageous political figure who worked easily on both sides of the aisle. Bush 41 oversaw the end of the Cold War without claiming credit or belittling the Soviets, pushed the Iraqis out of Kuwait with a broad international coalition, and raised U.S. taxes when it was necessary and when he probably recognized it could mean he would only be a one-term president.

Such was the character of George H.W. Bush. I proudly voted for him in 1988—the last time I voted for a Republican presidential candidate.

Ambassador Parker Borg was in the Foreign Service from 1965 to 1996. Among his overseas postings were ambassador to Mali and Iceland; he never went to Burma/Myanmar because the Senate after many months denied his appointment because of human rights issues in the country. He later worked on national security issues at the Center for International Policy and taught international relations at American universities in Rome and Paris.

A Moment That Will Always Make Me Smile

BY JENNIFER DAVIS

I was posted in Beijing and just starting out as a professional photographer. I had the honor of being selected as the official photographer when George H.W. Bush and his wife visited the embassy in 2008. I was clicking away as he walked in front of me down the middle of the aisle lined with all the visitors there to see him.

Suddenly he stopped, mid-walk, and said: “Dear, I don’t think that flash is working.”

I died on the spot—but I cherish what was an insignificant moment to a great man, yet one I will never forget and that will always make me smile.

Jennifer Davis is a former FS family member and professional photographer.

Presidential: George and Barbara in the House

BY JIM NEALON

George H.W. Bush with his granddaughter in Beijing, 2008.

U.S. State Department / Jennifer Davis

It was 2002, and my family and I were living in Budapest. I was the public affairs officer at the U.S. embassy there. We were privileged to live in a beautiful pink house next door to our ambassador’s residence. And that’s how we first met George and Barbara Bush.

The Bushes were good friends of our ambassador, Nancy Brinker, and they’d come to visit her. Hosting a former president and first lady was a big logistical lift for the residence staff. Along with the former first couple, there was the Secret Service security detail and others who had to be housed and fed; there were receptions to be hosted and meetings to be arranged. When the ambassador proposed a tea so that Mrs. Bush could meet the spouses of embassy officers, my wife, Kristin, offered to host. Our house was convenient for Mrs. Bush, and it would take some of the entertaining load off of the ambassador. She readily agreed.

Embassy spouses gathered in our house at the appointed hour, and Mrs. Bush and the ambassador walked over from the residence. But surprise: When they entered our house, they had the former president in tow.

In his remarks to the group he said that, as a former ambassador who knew and appreciated the work of embassy officers and especially the unpaid but important work of their spouses, he couldn’t resist the temptation to join the party.

It was vintage George Bush. In his impromptu remarks to the group he was short on syntax but long on heart and sincerity.

“Walking over here, saw the bicycles in the yard, family, pride... Served in China, know what you do, nothing more important...” and so on. It didn’t matter that it wasn’t a great speech. What mattered is that the Bushes exuded sincerity, and it seemed to all of us that there was no place they’d rather be, nothing they’d rather be doing.

They stayed longer than they had to. They shook every hand; engaged every guest in conversation; and in those pre-selfie days, posed for pictures, taken by a real photographer, with each and every one of us.

When the last picture was taken, President Bush took the camera, handed it to me, and told me to take a picture of him posing with the photographer. Then he and Mrs. Bush went into the kitchen to greet the staff, and he posed for pictures with them, as well.

That, ladies and gentlemen, is presidential. Quiet, natural, unforced decency and dignity, an acknowledgement that the work of others is important, a recognition of the service and sacrifice of others.

Godspeed, George H.W. Bush. Godspeed, Barbara Bush.

Ambassador James D. Nealon, a retired career FSO, is currently a Wilson Center Global Fellow.

Holey Sweaters in Kenya

BY AMBASSADOR (RET.) WILLIAM “BILL” HARROP

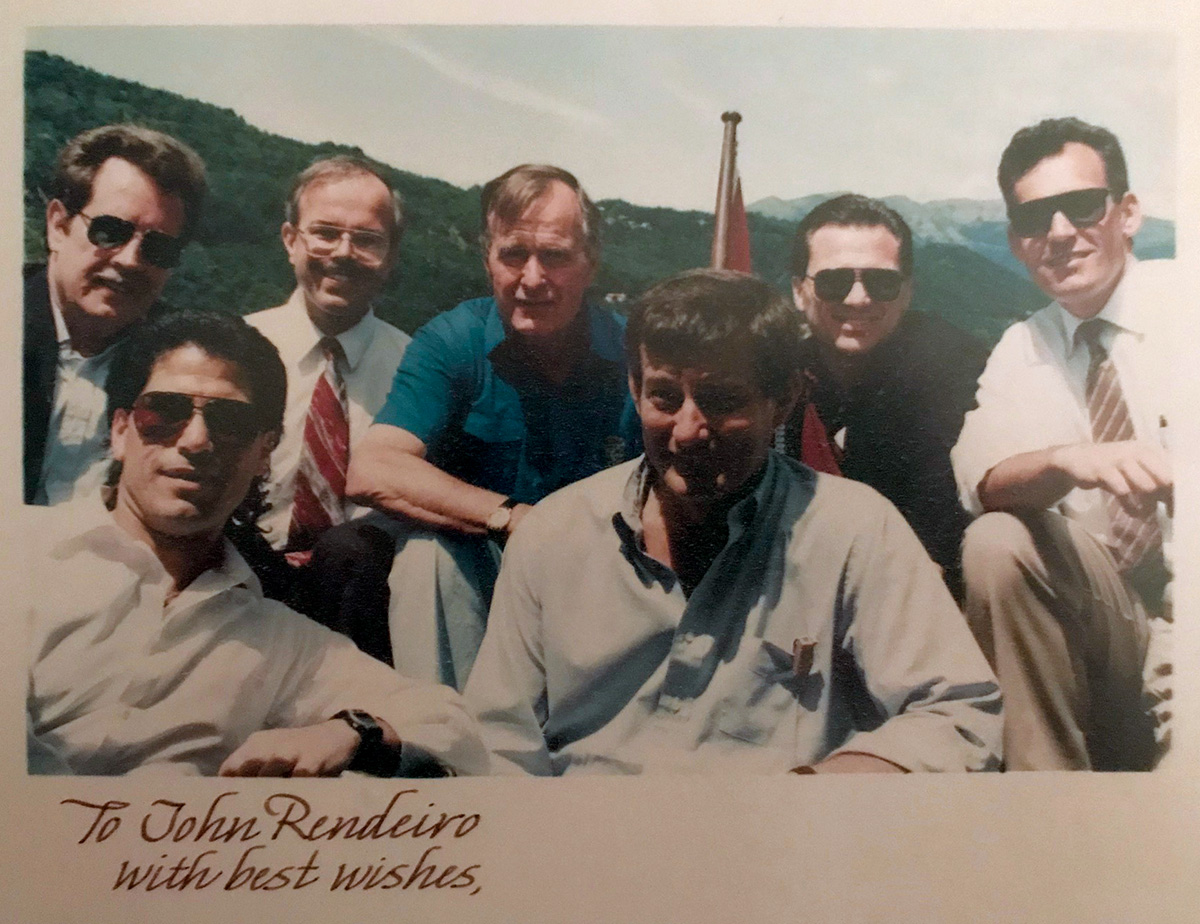

The 1993 boat ride on Lake Lugano. President George H.W. Bush (back row, center) and RSO John Rendeiro (to his right) are accompanied by Secret Service agents.

Courtesy of John Rendeiro

In 1982 George and Barbara Bush—he was then vice president—spent three days with my wife, Ann, and me in Nairobi. They were the most gracious houseguests we ever had.

One morning at breakfast, as Barbara was about to set off on a day trip to the highlands to visit Peace Corps Volunteers with Phil and Loret Ruppe (then Peace Corps director), we realized that Phil was not warmly enough dressed. Ann asked our steward to get out one of my sweaters to lend him.

On the party’s return that evening, Barbara said they had had a wonderful day but it was rather embarrassing since Phil Ruppe was wearing the most disgraceful sweater, full of holes. Then she realized to her embarrassment that the sweater was mine.

Two weeks later we received a handsome new sweater, sent from Bermuda where the Bushes had stopped to refuel on the way back to Washington. The card read, “From Old Foot-in-the-Mouth Bush.” On returning to Washington the Bushes telephoned each of our four sons to report that they had been with us in Kenya, and that we were fine.

They were a truly grand American couple we were honored to have met.

Ambassador William “Bill” Harrop served as ambassador four times during his 30-year Foreign Service career and was the recipient of the 2015 Lifetime Contributions to American Diplomacy award from AFSA.

A Professional Approach to Foreign Affairs

BY SUSAN B. MAITRA

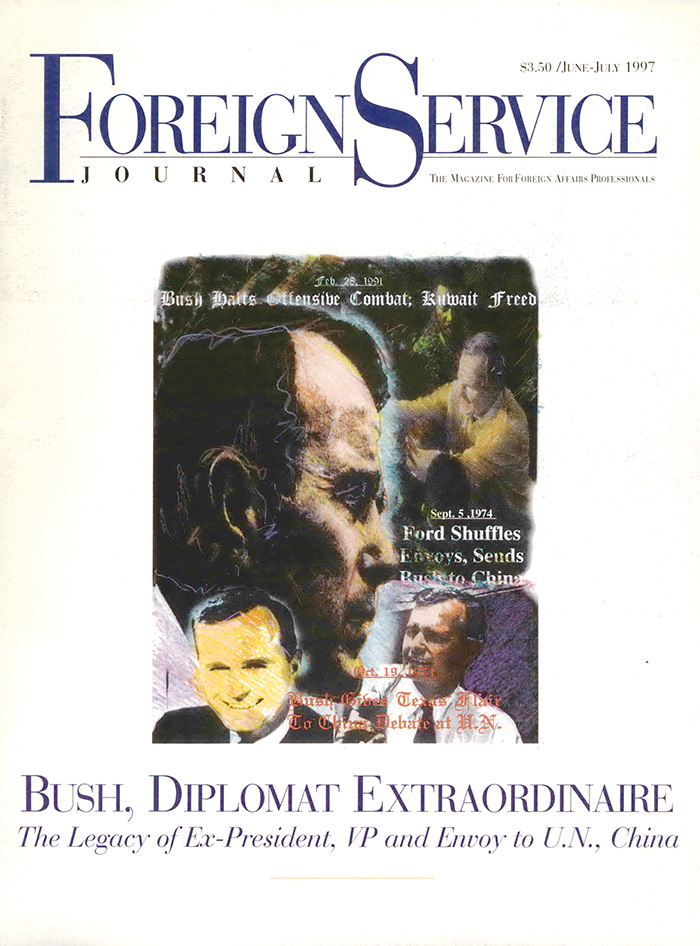

On June 26, 1997, in the Benjamin Franklin Room at the State Department, George H.W. Bush received AFSA’s Award for Lifetime Contributions to Diplomacy in recognition of his outstanding achievements in a series of high-level posts dealing with foreign affairs. The man and his achievements were discussed in detail in the Journal’s June-July 1997 focus honoring Bush’s legacy, “Diplomat Extraordinaire.” AFSA’s citation for the award particularly noted Bush’s professional approach to foreign policy and his regard for the professionalism and integrity of members of the Foreign Service.

In 2011, when the FSJ published a special focus on the breakup of the Soviet Union, we asked George H.W. Bush to weigh in. Then in his late 80s, Bush graciously offered his insights and reflections on those momentous times in an interview, “Charting a Path through Global Change.”

When AFSA’s executive director wrote to Bush, thanking him for the interview, the former president sent a personal note back: “Your letter was most thoughtful; but, I assure you, the pleasure was mine. I don’t accept many interview requests these days, but I was happy to be invited to interview for this issue of the FSJ. Your warm sentiments meant a lot to me. When you get to be an old guy, kind words go a long, long way. Warmest regards to you.”

Susan B. Maitra is the Journal’s managing editor.

The Measure of a Person

BY JOHN RENDEIRO

Warmth, friendliness and concern for all others were qualities for which President George H.W. Bush was rightly renowned. I had the good fortune to experience them firsthand on a couple occasions.

The first time was in Moscow, during the summer of 1991, when President Bush came to Moscow on an official visit for summit meetings with Mikhail Gorbachev and Boris Yeltsin. During that visit, the president met with the entire embassy staff in the embassy compound gymnasium, shaking hands and mingling with everyone. After that, he and Mrs. Bush met separately with the security staff; he took his time and in a very relaxed fashion spoke with each of us.

I mentioned that I had escorted his son Jeb on a post-earthquake visit to Armenia in 1988, at Christmastime when, as president-elect, Bush had sent Jeb and his grandson George to convey his condolences, concern and offers of assistance to the Armenian people. The president told us he had spoken at length to Jeb about that visit and thanked us for helping him with the trip.

Later, in June 1993, after leaving office, President Bush visited Lugano, Switzerland. As regional security officer in Bern, I coordinated security aspects of the visit with the Secret Service and the president’s staff. I met the president at his hotel, where he was, as usual, very friendly and chatted with me about his visit to Moscow.

The next day he visited Villa Favorita, where Baroness Francesca von Habsburg showed him her father’s art collection, said to be the largest private collection in the world after that of Queen Elizabeth II. Then we went to the dock on Lake Lugano for a boat ride that included the president, Secret Service agents, staffers and myself.

My memory of that boat ride, and my most enduring memory of President Bush, came when he, his staffers and Secret Service agents gathered up on the stern of the boat for a group picture. I was standing off to the side, by myself, at some distance from the group. The president saw me standing down there and said, “Hey, John, get up here!” He motioned me to sit right next to him, and the picture was taken.

If, as has been said, the measure of a person is how they treat those who can do nothing for them, that incident, for me, shows the unparalleled character of George H. W. Bush. I was a very small part of his visit, and he certainly didn’t need to pay me any notice at all; yet in that moment he treated me as if I were a VIP.

John Rendeiro, a retired Diplomatic Security agent, is currently a member of the FSJ Editorial Board.