Henry of the Tower Revisited

It’s time to take another look at how we remember 18th-century American envoy Henry Laurens.

BY THOMAS N. HULL

A portrait of Henry Laurens by John Singleton Copley, 1782.

National Portrait Gallery

“On a crisp London day in the autumn of 1780 a thickset, firm-jawed South Carolinian stood unhappily beside the Thames River, looking upward at the stones of the ancient fortress known as the Tower of London.”

A historical snapshot often does not capture the full picture. This certainly applies to the article “Henry of the Tower” by former Foreign Service Officer Ralph Hilton, published in the June 1969 Foreign Service Journal and excerpted in the June 2019 edition. Hilton introduces the American envoy Henry Laurens in a heroic pose, as described above, and proceeds to tell his saga, asserting that “with honor and sacrifice,” Laurens helped “to lay the cornerstone” of our Foreign Service. Revisited today, Hilton’s assessment does not stand up to scrutiny.

Hilton’s article relates how Laurens, en route to the Netherlands to negotiate a commercial treaty during the Revolutionary War, was captured by the British Royal Navy and incarcerated in the Tower of London. Upon being released, he participated in negotiation of the Treaty of Paris that officially recognized American independence from Britain. Although obscure today, Laurens was no ordinary envoy: He had been president of the Continental Congress when the Articles of Confederation establishing our first national government were enacted.

Hilton’s sympathetic portrayal of Laurens as a model of loyalty, suffering, and professional perseverance for modern Foreign Service officers to emulate may have seemed appropriate when written more than a half century ago. Now we view our country’s Founding Fathers through a wider lens as we reconcile our past with our ideals. In the case of Laurens, these aspects would include his leading role in slavery, how that was reflected in the Treaty of Paris, and how it affected U.S. foreign relations in the decades to follow.

“A Cosmopolitan Product of the Times”

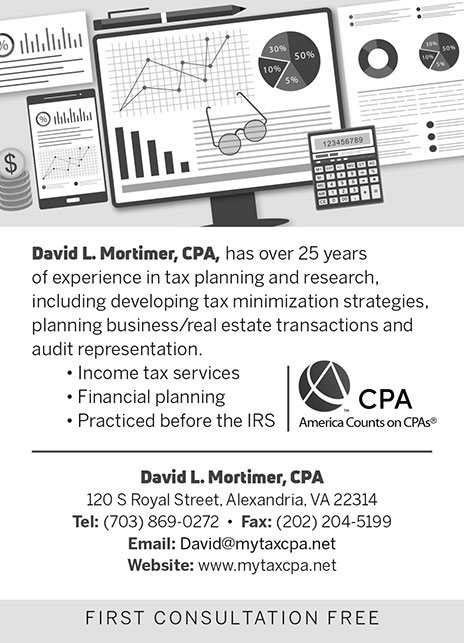

Laurens and his associates published this newspaper advertisement for the sale of enslaved people at Ashley Ferry outside Charleston, South Carolina, on April 26, 1760.

Library of Congress

Hilton tells us vaguely that Laurens was “a cosmopolitan product of the South Carolina plantation and mercantile society of the times.” This phrase smoothly obfuscates that Laurens owned six plantations with hundreds of slaves and was the largest slave importer in the American colonies in the 1750s and into the 1760s, thereby making him one of the wealthiest Americans at the time of the Revolution, according to Edward Ball’s Slaves in the Family (1998).

Hilton also informs us that while Laurens was in the tower, “his imprisonment … brought pressure from influential Englishmen for his release” without specifying who they were. The most influential was Richard Oswald, a wealthy merchant, financier, and confidant to the prime minister. He was also a prominent slave trader.

Sir Simon Schama describes Oswald in his book Rough Crossings: Britain, the Slaves and the American Revolution (2005) as “a slave trader who had made a cool fortune from his slaving entrepôt of Bance Island at the mouth of the Sierra Leone river, where he bought slaves from the Temne people. And when those human cargoes had docked at Charleston en route to being auctioned for the low country plantations of South Carolina it was none other than Henry Laurens who took a nice ten per cent of the transaction.”

These slaves were the economic engine of the Carolinas and Georgia in the 1700s because they brought skills from West Africa’s Rice Coast that the British lacked. Rice was the primary product of those colonies long before cotton and was the main source of wealth for Laurens and other plantation owners.

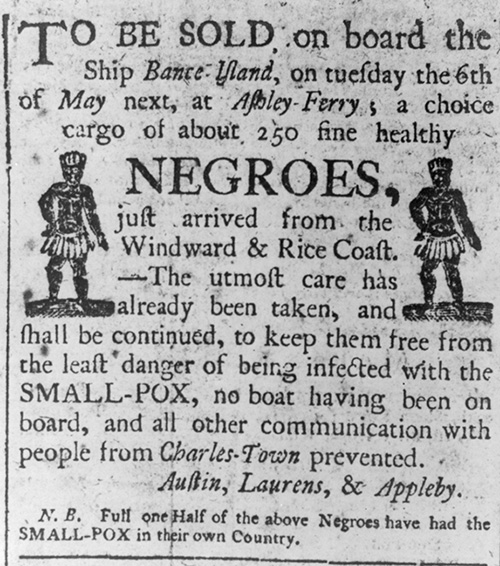

This commercial relationship proved significant when Oswald was named the lead British negotiator of the Treaty of Paris and Laurens was added to the American delegation. Due to poor health exacerbated by the damp chill and foul air while in the tower, Laurens went to the south of France to recuperate and only joined fellow peace commissioners Benjamin Franklin, John Jay, and John Adams on the final day of negotiations, Nov. 29, 1782.

Laurens’ Obfuscations

This unfinished painting by Benjamin West depicts (from left) John Jay, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Henry Laurens, and William Temple Franklin at the signing of the Treaty of Paris, 1783.

Album / Alamy Stock Photo

Hilton, citing Adams, makes the point that Laurens put forth, and the negotiators accepted, a proposal that the British reimburse the Americans for any property that they took when withdrawing. Again, Hilton obfuscated an important point—namely, that Laurens was equating human beings with property in a founding document of the United States.

A more forthright description of what occurred is provided by David McCullough in his biography John Adams (2001): “Laurens’s one contribution to the proceedings was to provide a line to prevent the British army from ‘carrying away any Negroes or other property’ when withdrawing from America. Oswald, who had done business with Laurens in former years, when they were both in the slave trade, readily agreed.”

The Laurens amendment protecting the interests of slave owners became a point of contention between the British and Americans almost immediately upon the signing of the Preliminary Treaty of Paris on Jan. 20, 1783. At that time, the remaining British troops under General Sir Guy Carleton had retreated to New York along with 3,000 liberated slaves. During the Revolutionary War, the British had offered freedom to any enslaved person, male or female, who deserted a rebel owner and crossed into British-held territory. Thousands did so, including those of prominent patriots George Washington, James Madison, and Patrick Henry.

“Prophets and Rebels”

When General Carleton met with General Washington in May 1783 to discuss the terms of the British withdrawal from America, the first item on Washington’s agenda was “the preservation of Property from being carried off, and especially the Negroes.” According to Adam Hochschild’s account in his book Bury the Chains: Prophets and Rebels in the Fight to Free an Empire’s Slaves (2005), Washington was infuriated to learn that some had already embarked and insisted that the remaining be turned over in accordance with the terms of the peace treaty. Carleton refused, contending that the liberated slaves were not property covered by the treaty because of the earlier British proclamation giving them freedom, but he conceded that slave owners might eventually be compensated for their losses.

Southern slave owners, encouraged by the Laurens provision, descended on New York in gangs to recapture their human property. Terror and violence ensued, forcing Carleton to evacuate the former enslaved to the nearest British territory, which was Nova Scotia. However, Nova Scotia proved inhospitable, and in 1792 most of them sailed back to Africa with the support of the British antislavery movement and government where they settled Freetown, the capital of present-day Sierra Leone.

Laurens was equating human beings with property in a founding document of the United States.

The issue of compensation for human beings as property sparked by Laurens lasted for decades with strong resistance from Britain where the antislavery movement was strong. The matter was not resolved until arbitrated by the tsar of Russia in 1826, with the British agreeing to pay American slave owners or their heirs half the market value of their former slaves.

A Misleading Vestige

The significance of the enslaved Africans shipped from Bance Island (now known as Bunce Island) to Charleston has not been lost—but not in ways that Laurens would have anticipated. The contributions by their American descendants to our country’s development and diversity have been significant. To recognize that connection and to bear witness to the horrors of the slave trade in which Laurens and Oswald engaged, the Department of State made grants from the Ambassadors Fund for Cultural Preservation to Syracuse University in 2007 and the World Monuments Fund in 2017 to protect the remaining ruins on Bunce Island.

As former Secretary of State Colin Powell wrote in his 1995 autobiography My American Journey, when visiting Bunce Island in 1992: “I felt something stirring in me that I had not thought much about before. … I am an American. … But today I am something more. I am an African too. I feel my roots, here in this continent.”

Hilton’s portrayal of Laurens as a hero of American diplomacy and a precursor to the Foreign Service that rests in the archives of The Foreign Service Journal is a misleading vestige of an era when the complicity of our Founding Fathers in slavery was overlooked. This needs to be rectified by telling the truth of who Henry Laurens was and what he represented. His values were not the “cornerstone” of the Foreign Service. Although it has been asserted that he renounced slavery at the end of his life, he still owned 298 slaves shortly before he died in 1794.

When sharing or linking to FSJ articles online, which we welcome and encourage, please be sure to cite the magazine (The Foreign Service Journal) and the month and year of publication. Please check the permissions page for further details.

Read More...

- “Henry of the Tower” by Ralph Hilton, The Foreign Service Journal, June 1969

- “Robert C. Schenck: Political Ambassador and Scoundrel” Stephen H. Muller, The Foreign Service Journal, November 2014

- The Papers of Henry Laurens, National Archives: National Historical Publications and Records Commission