This is How We Tweet

Twitter meets the State Department bureaucracy.

BY BEN EAST

Assistant Secretary Crickshaw wants to tweet. His request (order) reaches us in Electronic Media via the staff aides in the front office, setting in motion a whole series of actions that repeat the actions of the day before and the day before that, all the way back to the day we first tweeted, which nobody knows exactly when that was.

First, we initiate the Interagency Process to gather the Briefing Checklist, the Scene Setter, the Draft Remarks and all other documents related to the event the assistant secretary wants to have us tweet for him about. We then consult the lead office (in this case, Youth Rights/Worldwide Engagement/ Sports Organizations/Diplomacy for Underserved Males—YR/WE/SO/DUM) for an analysis of the pros and cons of tweeting. The analysis is strictly pro forma, of course: we have our orders. So we will complete the process per the standard operating procedure, right down to tweeting at the exact second of the precise minute of the chosen hour, no sooner and no later, as presented in the Tweet Strategy Timeline, which we are about to draft.

While YR/WE/SO/DUM completes the analysis, there is time for a quick cup of coffee and lemon pound cake from one of the many Starbucks within acceptable range (7 minutes) of the office. Upon return, we open the requested documents, unless they haven’t arrived, in which case we send a second (but not yet shrill) request, and then call the staff aides or drafters or clearers for bootleg copies that might be stuck somewhere in the process.

The Scene Setter tells us why the assistant secretary is involved in a particular program, and should contain the nuts and bolts on audience and message. Without reading the Scene Setter we have no idea when, where, why or how the assistant secretary is giving a speech, signing an accord, lobbying for war, etc., and therefore can make no logical recommendation about possible tweets in the Tweet Recommendation Package that has been requested (ordered).

Next we review the Draft Remarks, which are probably different from what will become the Cleared Remarks, which we will only get at the very last minute. But draft remarks will give us an idea of what the assistant secretary wants us to say for him about a particular issue, which we already probably know from previous clearances, but want to confirm because of what happened to us the last time we made an assumption. Finally, we consult the timeline in the program and decide on a suitable point at which to tweet the key message.

Justification

Now we are ready to draft, in rank order, three to five proposed tweets of 140 characters or less each, using no symbols, slang, acronyms (except USA and USG), emoticons or other non-standard American English grammar constructions (contractions and ampersands are OK, but “OK” is not). For each proposed tweet, we assign a proposed time for the tweet to be sent, with a brief explanation in 50 words or fewer of how the order creates a holistic message consistent with other messaging—even though we know that only one tweet has been requested and that therefore only one tweet will be used. This document is called the Tweet Strategy Timeline.

The next part is tricky. In the next part we draft the Justification. We must justify this request from the assistant secretary through the staff aides to us, for him. It’s not the assistant secretary’s job to justify his own requests. Justification is necessary, however, in the event that someone else of significant rank asks about the tweet.

For the clearances that haven’t come in, it is time to send that shrill e-mail demanding clearance as soon as possible.

The tricky part is that the assistant secretary must approve all justifications done for him by others. Devising justifications requires guesswork and, in the absence of strategy, assumptions, which as we’ve noted can be hazardous. The danger exists that the rationale won’t be strong enough to convince the assistant secretary (who had the idea in the first place) that it was a good one, which in principle is like saying it is a bad idea, which is a definite no-no.

Once we have a strong justification, we send the Tweet Recommendation Package around to every section and agency with a stake in the program, always including the regional bureaus for approval at the country desk level, since everything we do is scrutinized for potential insult to our partner nations; to the public affairs office; and to our colleagues in Print, YR/WE/SO/DUM and all the substantive principal deputy assistant secretaries and deputy assistant secretaries. We copy the staff aides so they can track the progress and not call us for updates while we wait.

There is no waiting in this office, even after we send around our Tweet Recommendation Packages for clearance. While the Package is out for clearance, we begin clearing the dozen or so other Packages that have come in from other sections and agencies, including Briefing Checklists, Scene Setters and the dreaded press releases from the guys in Print.

The Print Shop

Boy, do they have it rough over in Print! While our products are limited to 140 characters, the Print guys’ pieces run between 500 and 1,000 words. This leaves more than enough room for criticism from everyone in the clearance process—from those already too busy with their own drafting of Packages to catch any errors all the way up to the assistant secretary himself, who isn’t busy at all and therefore easily picks apart the 1,000-word press releases without even reading them, since he has his staff aides for that.

True, the folks in Print aren’t doing Strategies, Timelines or Justifications. But in addition to their press releases (of which there can be half a dozen per day), they are creating Packages for op-eds, public remarks and advertisements soliciting funds to support our various public-private partnerships. The folks in Print spend hours on the telephone with staffers from our embassies and consulates and with host governments, gathering quotes, bilateral agreement, photos, and so on, for inclusion in their releases. As a rule we clear on all of Print’s stuff first, since they are our brethren and we feel their pain most acutely. Sometimes we have to fill in for them.

Next we clear on Packages from Culture, since they are our next closest kin in public affairs, and we know their programs—youth exchanges such as the one we’re working up this tweet for, visiting scholars, artists on tour and American thematic experts on core topics like the spread of democracy (tempered by a respect for the sovereignty of nations), the assurance of human rights (tempered by respect for animal and environmental rights) and prosperity for all (tempered by the understanding that prosperity is simply not possible for all). Then we take on the clearances from other sections and agencies in rank order by deadline, avoiding the most poorly written material for as long as we can.

The Afternoon Rush

By the time lunch is over (sandwich, apple and water at the desk), it is time to follow up with others for their clearance on our Tweet Recommendation Package. Hopefully we have most clearances by now and we can just send the Package forward, marked FOR EXECUTIVE CLEARANCE, for the staff aides to print and put on the assistant secretary’s desk. The assistant secretary only clears on hard copy, which is then sent back down electronically as a PDF filled with scrawled notes that require us to squint and hold up the pages to the light for interpretation. But we are getting ahead of ourselves.

For the clearances that haven’t come in, it is time to send that shrill e-mail demanding clearance as soon as possible and putting a default clearance time in the subject of the e-mail, followed by a phone call. It can be useful to paste the contents of the package into the body of the e-mail. This is so the material can be read and cleared more easily via BlackBerry, or smartphone, in the unlikely event that someone in the clearance process actually managed to leave the building to interact with contractors, think-tank experts or foreign diplomats assigned to the embassies all around town.

Once the default hour has elapsed, we walk around our own office to confirm our internal clearances, saving the acting office director for last. The later we get to her, the more likely it is that she’ll be lost at the bottom of a pile of other clearances from all her work as deputy director, in addition to the added responsibilities of being the acting head of office. Getting her clearance then will be as simple as looking through her office door to confirm that she is still alive.

With messages of 140 characters or less, we are usually the first in line at the front office suite when the staff aides invite us to review our Tweet Recommendation Package with the assistant secretary. If we have fallen behind, then by the time we get there, the assistant secretary’s suite on the Sixth Floor is a maelstrom of nervous energy emitted by the other bureaucrats knocking the parquet floors with the heels of their patent-leather shoes as they wait their turn for review.

Nobody makes eye contact or shares more than a few innocuous words of greeting as they pace, until the office management specialist appears at the entrance and invites in the next victim. It can be tragic to watch successive officers emerge, increasingly sullen as the afternoon wears on—except, of course, for the political counselor approaching retirement who is already numb from a lifetime of criticism.

To the Inner Sanctum

But if, as usual, we are invited early, we cruise across the parquet floors past the staff aides’ watchful eyes and enter the Inner Sanctum of U.S. Policy Formulation and Implementation (as the assistant secretary himself refers to his office). The large, woodlined room is filled with the evidence of a lifetime of schmoozing in foreign capitals.

Most prominent are the rusty spur of a Paraguayan general killed in the Chaco War, a copy of the Bible from the Vatican signed by the Pope, a folded Old Glory that once flew over the embassy in Berlin and is now retired to a tricorner case and, next to the sofas lining the informal seating area, the model trains and airplanes that clutter the surface of an end table built by the General Services Office for that express purpose. On the floor are Persian carpets and on the walls are plaques, portraits, framed news clips, photos of the assistant secretary with leaders of the world and other evidence of his grandeur.

Seated behind his desk, the man himself waits for the door to be pulled shut by the Office Management Specialist before clearing his throat. He says nothing, for it is our duty to begin.

“We liked your recommendations, sir,” is a good place to start.

“On the contrary. You’ve written a very good Twitter.”

We thank the assistant secretary. We are not smug, and we do not correct him on “tweet” vs. “Twitter.” We are well aware that his satisfaction goes only so far, and we hold our breath in anticipation of qualifiers like “however” and “but.”

“But, do you think there’s room to include a democracy message?” he asks.

“If you want one, sir, there is room.”

“What about economic growth and prosperity?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Environment? Energy? Peace? Security?”

“All of them, sir.”

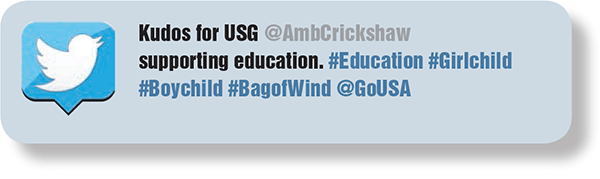

“I see this tweet is limited to U.S. support for educating male youths. Do you think it’s possible to work in something about educating the girl-child?” (The assistant secretary never says “boys” or “girls.”)

“If you would like, sir, we can develop a master message that covers all of our top-line messages.” We know from past experience, from just yesterday in fact, and the day before that and the day before that, that the assistant secretary is keen on jargon and enjoys knowing our team can create such things as top-line messages. We are pleased, though still not smug, to see him nod.

“Very well,” he says. “For Twitter?”

“For such a lengthy message, we may need to use Facebook.”

“Facebook?”

Tomorrow will be the first day in a long line of forgettable days in which the assistant secretary sends a “request” for us to use Facebook on his behalf.