It Deserved an Oscar

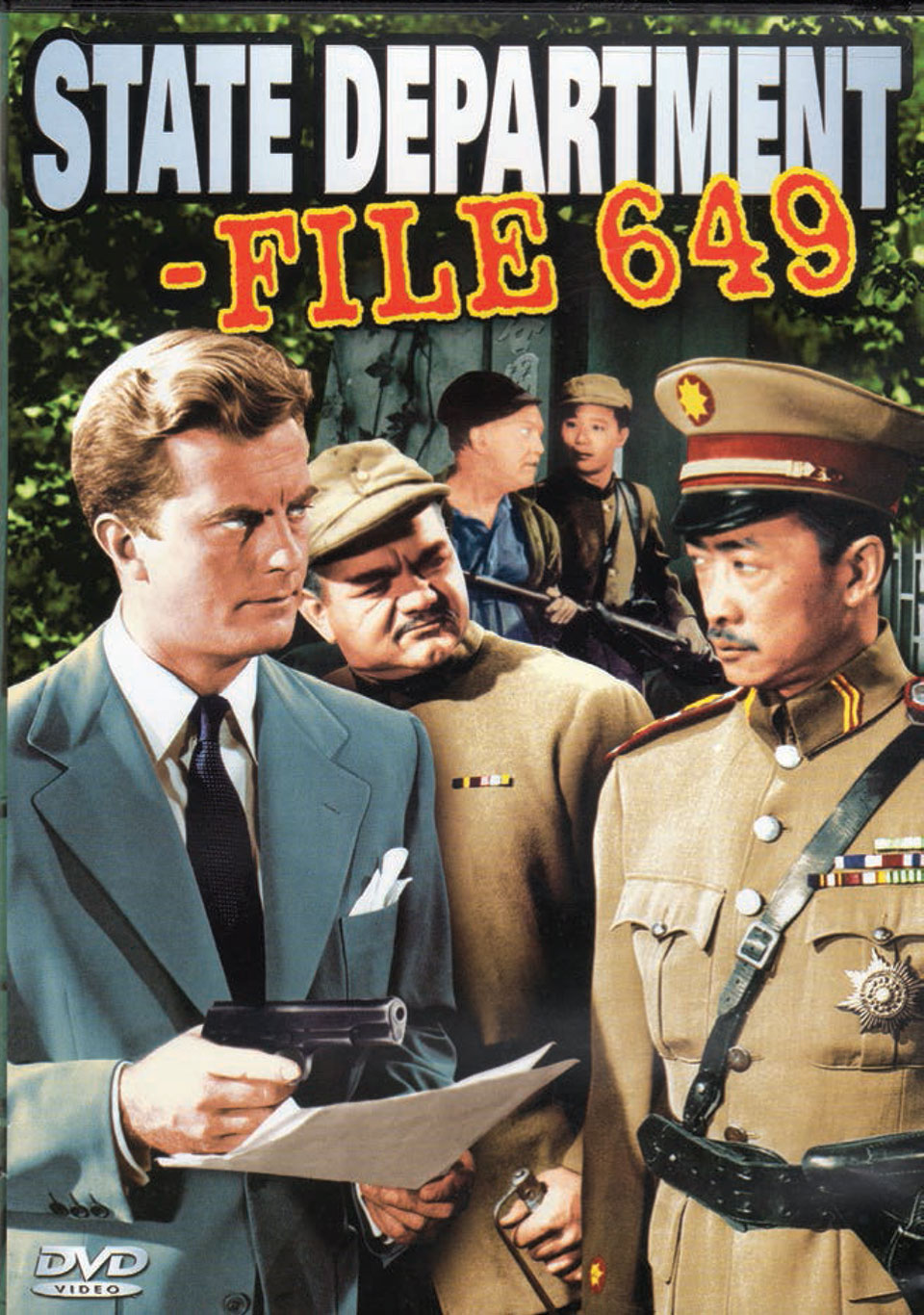

For those of us in the Foreign Service, “State Department File 649” is our cinematic showcase, William Lundigan our star, and Virginia Bruce our Best Actress.

BY DONALD M. BISHOP

Ah, the movies! They entertain. They make us cry, or cheer. They lead us down the paths of love, or fear. In front of the big screen our blood runs cold, or rushes in anticipation. Films introduce us to the regions of America and the countries of the world. They take us to places—prisons, courtrooms, airline cockpits, mines, ranches, submarines—we are unlikely ever to visit in real life.

Films also portray and introduce professions, giving visibility, dignity and, perhaps, adventure to many walks of life. What fisherman does not see something of himself in Spencer Tracy (in “Captains Courageous”) or George Clooney (in “The Perfect Storm”)? Robin Williams in “Dead Poets Society” and Richard Dreyfuss in “Mr. Holland’s Opus” surely make every teacher walk a little taller. What American can see a locomotive without thinking of Denzel Washington (“Unstoppable”) or Barbara Stanwyck (“Union Pacific”)? Tell lawyer jokes if you will, but who does not admire Gregory Peck in “To Kill a Mockingbird” and Jimmy Stewart in “Anatomy of a Murder”?

Once upon a time, Hollywood helped Americans get to know our diplomatic corps through magnetic, attractive and well-tailored actors like William Lundigan and Virginia Bruce. I refer, of course, to the stars of that classic film directed by Sam Newfield, “State Department File 649.” I’m still hoping that Denzel, Kevin, Keanu or Leonardo, paired with Sandra, Angelina, Renee or Lucy, will star in a similar diplomatic blockbuster.

Yes, “Argo” gave us a slice of embassy life and quiet courage, but the hero worked for the CIA. For those of us in the Foreign Service, “State Department File 649” is our cinematic showcase, William Lundigan our star, and Virginia Bruce our Best Actress.

This 1949 indie classic long lay in undeserved obscurity, until Alpha Video recently made it—original, unedited, unenhanced, unrestored—available in its rich, original CineColor on DVD and online. Netflix can send you the film, or you can find it on YouTube (or publicdomainflicks.com). For those of you in Washington, there’s a copy at the Ralph Bunche Library. Wherever you view it, “State Department 649” deserves pride of place at the next Foggy Bottom Film Festival. Let’s look, then, at the motion picture, its casting and what makes it such an enduring portrait of the United States Foreign Service.

Dramatis Personae

Playing our Foreign Service hero, Ken Seeley, was the handsome William Lundigan (1914-1975). While studying at Syracuse University Law School, he worked part-time as a radio announcer. A Universal Studios executive heard his voice, and signed him in 1937. His many prewar screen credits included “Dodge City” (1939), “The Fighting 69th” (1940) and “The Sea Hawk” (1940). In “Santa Fe Trail,” also released in 1940, he joined Ronald Reagan in the cast.

During the war, Lundigan enlisted and took his place behind, rather than in front of, the camera. He was a Marine Corps combat cameraman in the battles of Peleliu and Okinawa. Returning to Hollywood, he starred in “Pinky” (1949), “Love Nest” (1951), “The House on Telegraph Hill” (1951), “I’d Climb the Highest Mountain” (1951), “Inferno” (1953) and many other movies.

Like his friend Ronald Reagan, Lundigan leaned conservative in his politics. In the 1964 presidential campaign, he, Walter Brennan, Chill Wills and Efrem Zimbalist Jr. were a celebrity Hollywood foursome supporting the Republican candidate, Barry Goldwater, in his run against President Lyndon Johnson.

Playing opposite Lundigan in our Foreign Service blockbuster was Virginia Bruce (1910-1982). As the more famous star, she received top billing. She had already played the title role in the 1934 version of “Jane Eyre,” and in 1936 she introduced the Cole Porter song, “I’ve Got You Under My Skin” in “Born to Dance,” melting Jimmy Stewart’s heart. Her long list of other film masterpieces includes “The Mighty Barnum” (1934), “The Great Ziegfeld” (1936) and “Pardon My Sarong” (1942), in which she starred with screen greats Abbott and Costello. Her performances in “Adventure in Washington” (1941), “Action in Arabia” (1944) and “Brazil” (1944) no doubt informed and shaped her work in “State Department File 649.”

Other Hollywood deities appeared in the cast, as well. Jonathan Hale surely deserved a statuette for his best-ever portrayal of “the Director General.” Philip Ahn and Richard Loo were unjustly neglected at the Oscars as Best Oriental Heavies. And it’s inexplicable that the 1949 award for Actor with the Best Makeup did not go to the professional wrestler Henry “Bomber” Kulky, appearing as one of the Mongolian “bandits.”

Story Line

The film opens with a stirring narrative introduction, referring to the Foreign Service as “unsung and unhonored heroes;” “the Silent Service that works under the most difficult and dangerous conditions, which require tact, diplomacy and courage;” and “men and women who have given their health and their lives in obscurity,” often “tortured, maimed, stricken by disease, disaster and death.” I thought that Navy submariners were “The Silent Service,” but who am I to dispute such plain words of truth, so well deserved? From the platen of a scriptwriter, pure inspiration!

The film’s nonpareil plot then follows Seeley (Lundigan) as he appears before the examination board, enters the Foreign Service, learns Chinese at the Foreign Service Institute and is assigned to a faraway consulate in postwar north China, “Mingu,” somewhere near Mongolia. In Washington, he meets Marge Waldon (Bruce), and they meet again when she visits Mingu as a rover.

There’s trouble up north—but from “bandits,” not communists. A local strongman, Marshal Yun Usu (Richard Loo) hopes for recognition by the government in Nanking, but our brave American diplomats know him to be a smuggler and a power-mad scoundrel. When he and his uniformed thugs take over the consulate and kill the loyal Chinese radio operator, Johnny Han (Victor Sen Yun, in one of his most memorable roles), Ken must use his Marine veteran’s knowledge of explosives and his Foreign Service courage to foil the warlord’s plan. The film closes with Ken’s name being chiseled on the AFSA memorial wall at the State Department.

The entire staff of Consulate Mingu consists of a consul, a vice consul, a secretary and a Foreign Service National.

Immortal Lines

Alas, none of the lines in Milton Raison’s boffo script have become as common as “Make my day” or “I’m shocked, shocked to find that gambling is going on here.” But members of the Foreign Service can well appreciate these quotes:

Consul Reither: “I think I’d better inform Washington.”

Ken: “I’m just a vice consul, a dime a dozen.”

Marge: “This happens to be a post where the clerical work is quite superior.”

Colonel Aram: “The marshal is very angry. He has broken your radio.”

Pay no attention to the crabby review on the Fandango website: “The characterizations are of the cardboard variety and the dialogue is straight out of Fu Manchu.”

Not a Foreign Policy Primer

“How many modern viewers will understand the backdrop of what the script refers to as “the present crisis”—the fact that, in 1949, this meant the communist takeover of China, with Mao Tse-tung wresting control from the pro-American Generalissimo Chiang Kai-Shek? Communism might have made a credible opposing force to the heroic American men and women of the State Department, but the filmmakers apparently wanted to play it safe. Not knowing which way the cats were gonna jump in old Peiping, they inserted a stereotypical ‘Mongolian warlord’ figure as the opponent to America’s interests, a ‘Yellow Peril’ threat that was dated at the time and hasn’t aged well since.”

Promoting exports is one Foreign Service role that could not fit in the film, but there is a subtle message on behalf of American products. When the warlord comes, he arrives in a sleek, long trailer, obviously made in the USA. Its arrival—with cavalry escort, no less—never fails to evoke laughter among 21st-century viewers. No doubt that reaction expresses joy at the successful promotion of American vehicles in north China markets.

The Enduring Spirit of the Foreign Service

Still, as the film comes to its conclusion, our brave vice consul confronts the warlord and expresses the spirit of the Foreign Service and America: “I am on the winning side, Marshal. I represent an ideology that recognizes the dignity of the individual, that holds all men to be free and equal under God. You represent murder, rape and slavery in the name of the law. You’re a mad dog that must and will be destroyed.”

Admittedly, these flag-waving lines now seem corny and anything but “diplomatic.” The whole tone is dated, oh so 1940s. Yet ... don’t murder, rape and slavery still stalk the world? Don’t “dignity of the individual” and “free and equal under God” still express the best American sentiments, no matter how imperfectly we advance them? Don’t we still believe in—and represent—these old values?

So here’s to you, Virginia! Here’s to you, Bill! And here’s to “State Department File 649!” Surely, Mr. Spielberg, this classic deserves a remake.