Spy vs. Spy, Romanian Style

Reflections

BY LUCIANO MANGIAFICO

Well before 1977, when I was assigned to Bucharest to head the embassy’s consular section, I was already well aware that Securitate, the state security service, kept close tabs on all foreigners, both at work and home. They also used a medical clinic across the street from the embassy to observe our visitors and intercept communications.

When I arrived, our ambassador was Harry G. Barnes Jr., a Foreign Service legend who was famous for having had a shoe bugged by Romanian intelligence while he was deputy chief of mission in Bucharest years before. The Bureau of Diplomatic Security subsequently exhibited the shoe during Washington security briefings to illustrate the lengths to which hostile powers would go to obtain intelligence.

As Barnes later recounted, “Dick Davis (his ambassador at the time) wrote back to State: ‘Don’t you think you ought to reimburse Harry for the price of new shoes?’ The department’s response was, ‘We will replace the one shoe.’ He finally persuaded them to pay for a pair.”

We came up with a crazy solution that worked for months, until Securitate finally caught on.

In Romania, consular services often involved human rights issues. For instance, in 1979 German Chancellor Helmut Schmidt signed an agreement with Romanian President Nicolae Ceausescu that granted about $368 million in trade credits in exchange for the yearly emigration of some 10,000 to 13,000 ethnic Germans. Deviously, however, the Romanians refused to issue them exit visas to West Germany, but instead indicated the United States as their destination.

At first, we issued them tourist visas, assured that German officials would get them off the plane in Frankfurt. Alas, a couple of them ended up in New York and the Immigration and Naturalization Service raised Cain about it, so the department told us to stop doing that.

Fortunately, State left us a loophole by saying nothing about issuing other kinds of visas. So we switched to transit visas, as if the bearers were traveling to Frankfurt via New York. In cooperation with West German officials, who closely monitored the whereabouts of the “transit passengers,” that stratagem worked.

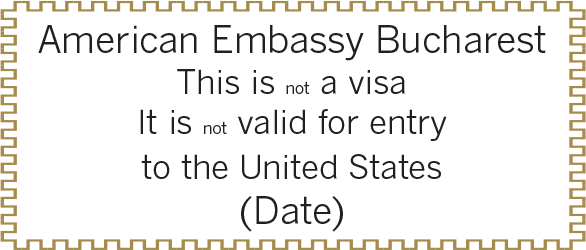

To help Romanians who were ineligible for U.S. refugee status travel to other countries, we came up (in cooperation with Canadian diplomats) with a crazy solution that worked for months, until Romanian security finally caught on. We had rubber stamps made in Vienna that read:

After we stamped their passports, we advised the bearers to take the afternoon train to Belgrade so that they would arrive at the border crossing point into Yugoslavia in the middle of the night. Frontier guards who were not fluent in English and sleep-deprived tended to miss seeing the word “not” since it was in much smaller type, or did not understand the significance of that disclaimer.

Either way, they usually assumed the bearer was bound for the United States (or Canada, which employed the same trick for its visas). Instead, the refugees then made their way to the refugee camp at Traiskirchen, near Vienna.

I also played postman for Constantin Rauta, a Romanian intelligence officer who had defected to the United States while on an advance trip for the 1974 visit of Pres. Ceausescu to Washington, D.C. Rauta had left behind his young wife and child, so I regularly delivered mail from him to them, and collected letters she wanted sent to him. She was finally allowed to leave Romania late in 1979, nearly six years after her husband had defected.

The guidance of my superiors and colleagues, the trust and camaraderie we developed, and the experience I gained during my two years in Bucharest all proved invaluable to me, both from a personal and a professional standpoint.