Jimmy Carter: Diplomats Remember

Katie Koehler with Ambassador to Nepal Peter W. Bodde and President Jimmy Carter at the embassy in Kathmandu, 2014.

Courtesy of Katie Koehler

The President’s Control Officer

NEPAL, 2014

My first-ever opportunity to serve as control officer came during my first tour in Kathmandu, where I was serving as the pol/econ office management specialist (OMS). President Carter had visited Nepal several times to support the Carter Center. I remember telling anyone who would listen that if he came to the embassy, I wanted to be his control officer. My family has strong connections to Georgia, and I really wanted to meet him. Everyone said he wasn’t going to come, but then at the last minute, he did! So, I think they felt like they had to let me be the control officer. He gave a great speech, without notes, and shook everyone’s hands, and took photos with the Marines before he left. I remember thinking, “Wow, I don’t know why everyone complains about being control officer, this was so easy!” Ha. One of my first Foreign Service memories.

Katie Koehler

Vice Consul

U.S. Consulate Guadalajara

Monitoring Elections in Port-au-Prince

HAITI, 1990

Jean-Bertrand Aristide with Jimmy Carter in Port-au-Prince, 1990.

Courtesy of Steve Kashkett

Most Foreign Service officers have stories about their experiences with prominent people during their careers. One of my most memorable ones is of Jimmy Carter, who came to Haiti in 1990, a decade after leaving office, as the head of an observer mission for the historic first free elections in that country. As the embassy political officer in charge of our election monitoring efforts, I spent the day escorting the former president to dusty polling places in the slums of Port-au-Prince. He was gracious, inquisitive, and tireless under difficult conditions and security threats—a true statesman. At his request, we took Carter to meet popular but controversial leftist presidential candidate Jean-Bertrand Aristide, who subsequently surprised most foreign observers by winning the election in a landslide. Sad to see him pass on …

Steve Kashkett

Senior FSO, retired

New Year’s Eve in Tehran

IRAN, 1977

My first and only contact with President Carter was during his overnight visit to the Shah of Iran on New Year’s Eve in 1977, when he praised Iran as “an island of stability” in an unstable Middle East. I had received a personal letter of thanks from the woman directing State’s new Bureau of Human Rights for something I had done as political counselor in Tehran, and I enjoyed a handshake and pleasantries as the president saluted the embassy’s senior officers and their spouses before climbing into Air Force One.

In retrospect (I am now 93 years old), President Carter had the misfortune to be pressured by many Rockefellers and others to let the shah into the United States for medical treatment. He was honest but could never convince a suspicious Ayatollah Khomeini—whose own maneuvers and half-truths had convinced Washington that he was the right foil to the Soviets—to admit the shah. Khomeini had, after all, released us Americans from the first takeover of the embassy back in February 1979. So, despite repeated warnings from our embassy in Tehran that we could never convince Khomeini, the second embassy takeover in November 1979 lasted 14 months—and lost Carter his reelection.

Happily, we all know this defeat did not stop President Carter from his unique lifelong devotion to truth, peace, and support of human rights around the world.

George B. Lambrakis

Senior FSO, retired

Brighton/Hove, England

The “Anti-Hero” with a Heroic Legacy

WASHINGTON, D.C., 1977

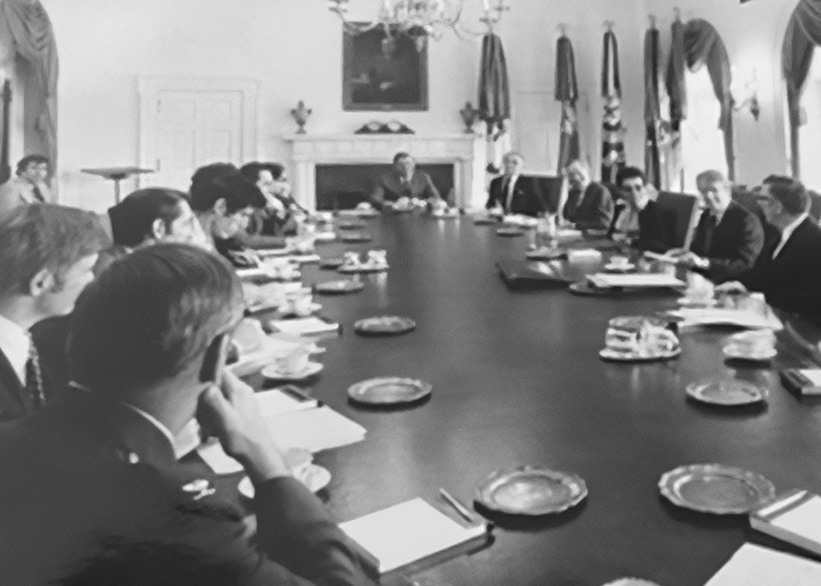

Kenneth Quinn was the interpreter and junior-most member of the delegation for the first postwar mission to Vietnam, led by Amb. Leonard Woodcock in March 1977. He is in the left corner of the photo, next to the window.

Courtesy of Kenneth M. Quinn

When Jimmy Carter entered hospice care in February 2023, Taylor Swift’s song “Anti-Hero” was atop the pop music charts. That caused me to reflect that “Anti-Hero” might have seemed the most appropriate appellation for the 39th president, when I first encountered him at a meeting in the Cabinet Room in March 1977. As an FSO with five years of experience in Vietnam, I had been selected as a member of the first postwar mission to be sent by the new president to Hanoi.

As I entered the West Wing, I noticed the absence of any photos of the new president, which made the White House feel bland and devoid of its prior grandeur. Carter’s informal attire, along with his refusal to have “Hail to the Chief” played when he entered the room during formal events, reinforced that anti-hero image.

At that meeting, however, I had the opportunity to observe President Carter’s “heroic” inner character. With deep empathy, he articulated the pain that families of the more than 2,500 U.S. military personnel who were still missing in Vietnam were enduring. Our mission was to begin accounting for those MIAs—a process that continues in 2025, the 50th anniversary of the end of the Vietnam War.

In July 1979, I again saw that empathy with the president’s decision to reopen America’s doors to the “Boat People” refugees from Vietnam, who were tragically dying at sea as they desperately sought freedom. I will never forget witnessing the spontaneous standing ovation that America received at the UN Conference in Geneva, when Vice President Walter Mondale announced President Carter’s decision to accept 168,000 Indochina refugees a year, thus saving the Boat People.

It is the ultimate irony that at what was arguably the most significant humanitarian achievement of his presidency, perhaps reflecting his anti-hero instincts, Jimmy Carter was not present.

Ambassador Kenneth M. Quinn

U.S. Ambassador to Cambodia, 1996-1999

President Emeritus, the World Food Prize Foundation

Des Moines, Iowa

President Jimmy Carter and Human Rights

BUENOS AIRES, 1976

I joined the Foreign Service in late 1975 and was assigned as the junior political officer in Buenos Aires in mid-1976. Legislation mandating a human rights office, annual report, and compliance at the State Department, championed by my home-state congressman, Don Fraser (D-Minn.), had been recently enacted, and Jimmy Carter’s election as president later that year raised human rights as a prominent bilateral issue. His election changed my life.

As the embassy’s first designated human rights officer, I met with victims of the Argentine junta’s repression and disappearances campaign, reported on abuses, drafted statements, and briefed diplomats and U.S. officials, including newly appointed Human Rights Coordinator Patt Derian.

In 1977 prominent Argentine human rights activist Adolfo Pérez Esquivel was kidnapped. I was among the first contacted by his family for help, and the embassy, under holdover Ambassador Robert Hill, applied intense pressure to force the junta to acknowledge his whereabouts. Tortured and held without trial for more than a year, he was eventually released. In 1980 he won the Nobel Peace Prize.

Human rights under President Carter became a significant issue in many, albeit not all, U.S. bilateral relationships, including the collapse of the Soviet Union, the move toward democratic rule in Latin America and Eastern Europe, humanitarian and refugee assistance, and U.S.-China relations. It changed my career trajectory as I found purpose in assignments managing refugee assistance in Central America, anti-narcotics, Kosovo, and, after retirement, 20 more years of work in refugee resettlement and assistance in Cuba, Jordan, Lebanon, and throughout the United States.

President Carter brought morality, dignity, and pride to representing the United States abroad and at home. May he rest in peace.

Yvonne Thayer

FSO, retired

Meeting My Role Model

PLAINS, GEORGIA, 2014

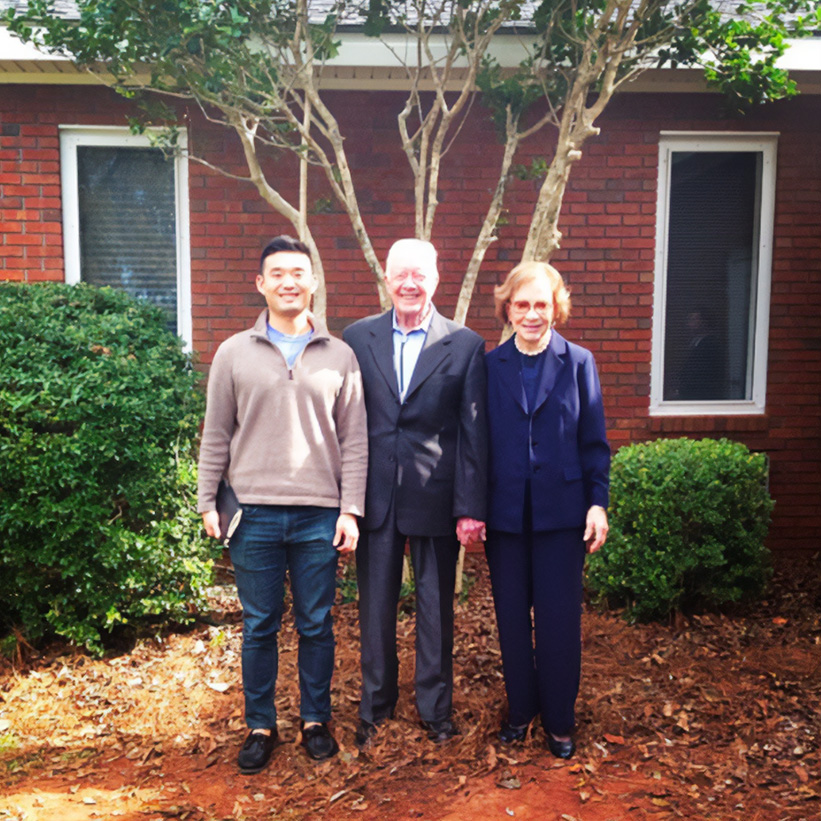

Jason Taehee Lee stands with President and Mrs. Carter in front of Maranatha Baptist Church in Plains, Georgia, 2014.

Courtesy of Jason Taehee Lee

During college, I wanted to give some percentage of my work-study earnings to causes I believed in, and the Carter Center was one of the foundations I selected. The more I learned about President Jimmy Carter and the Carter Center, the more inspired I grew to pursue public service. After graduation, I was commissioned as an officer in the U.S. Navy and served in the Navy’s Nuclear Propulsion Program, where President Carter had served during his naval career. Upon learning that President Carter would turn 90 years old in 2014, I realized I might have only a few more years to meet my role model, so I made my way from Washington, D.C., to the Maranatha Baptist Church in Plains, Georgia, to meet him and his lovely wife, Rosalynn. After the church service, I was able to meet and take a picture with my role model, and I was so thankful for his graciousness and encouraging demeanor.

His pursuit of truth and service to those around him are principles I try to embody in my personal and professional life. His life was truly one fully lived.

Jason Taehee Lee

Vice Consul

U.S. Embassy Phnom Penh

Giving Voice to the Voiceless

EGYPT, 2010

President Jimmy Carter with Maryum Saifee, 2010.

Courtesy of Maryum Saifee

This photo with President Carter was taken in 2010 during my first Foreign Service posting in Cairo. I was in charge of taking his son, Jack, and daughter-in-law, Elizabeth, to the pyramids while President Carter met with then-President Hosni Mubarak. I couldn’t help but reflect on President Carter’s leadership in crafting one of the most durable peace agreements in the region.

As someone who has spent most of my Foreign Service career working in public affairs, I often write into talking points “the U.S. needs to lead by example on [insert lofty goal].” It’s a way to acknowledge that while we aren’t perfect, we are actively trying to be better. President Carter spent a moment in time—how lucky for us it was a century—where he embodied this talking point. He lived it quietly and with humility, but he also used his platform loudly—no matter the blowback—to advocate for those who had no voice.

In reflecting on Carter’s legacy, I’m reminded our diplomacy has the power to build trust, and we have the capacity to be our better selves, to lead by example. The fact that every living president showed up in the front row of the National Cathedral at his funeral felt like a possibility only President Carter could manifest.

More than anything, President Carter’s consistency of character and commitment to framing human rights as not just a nice-to-have but a national security imperative will be the lessons from his legacy I’ll carry with me throughout my life and career.

Maryum Saifee

FSO

New York, New York

Honoring a Life Well Lived

ILLINOIS, 1976; SUDAN, 1993

In 1976 Jimmy Carter campaigned for president at the Foellinger Auditorium on the University of Illinois campus in Champaign–Urbana. I was fortunate to witness his speech. Many students felt his words encouraging following Watergate and the Vietnam War. America, similarly responding, brought him into office soon afterward.

During his presidency, human rights, environmental matters, and energy issues gained salience as not only U.S. policy priorities but also, gradually, as global concerns. No one can forget the breakthrough of the Camp David Accords in 1979. Inspired, the following year I joined the Peace Corps and went to serve as a community health development worker in the Philippines, which led to my interest in becoming a Foreign Service officer.

President Jimmy Carter was a good and decent man who cared deeply about humanity and devoted his life to making this world a better place.

In 1993, during my second tour as a Foreign Service officer, in Khartoum, I saw President Carter again, when he and his wife, Rosalynn, visited the embassy, where he posed for a photo with my children, Ginger and Jordan. Over the years, Jimmy Carter came to three other countries in Africa while we served there—Ethiopia, Mali, and Mozambique. In all, he had a heart for Africa and made an amazing 44 trips there.

We were delighted to brief him and to gain insights regarding his work to eradicate Guinea worm, support electoral processes, and construct affordable housing. I found great encouragement through my work as a diplomat in advancing our priorities and engaging foreign audiences.

The Carter Center, which was founded in 1982, collaborated with us and other like-minded partners to observe elections and promote human rights, and its work continues around the world today. Jimmy Carter, a sincere Christian who lived his enduring faith and values, stands out among heads of state as a servant leader. We, along with the world, honor his life well lived.

Ambassador Eric P. Whitaker

Department of State

Washington, D.C.

Welcome to Belgrade, President Carter!

YUGOSLAVIA, 1980

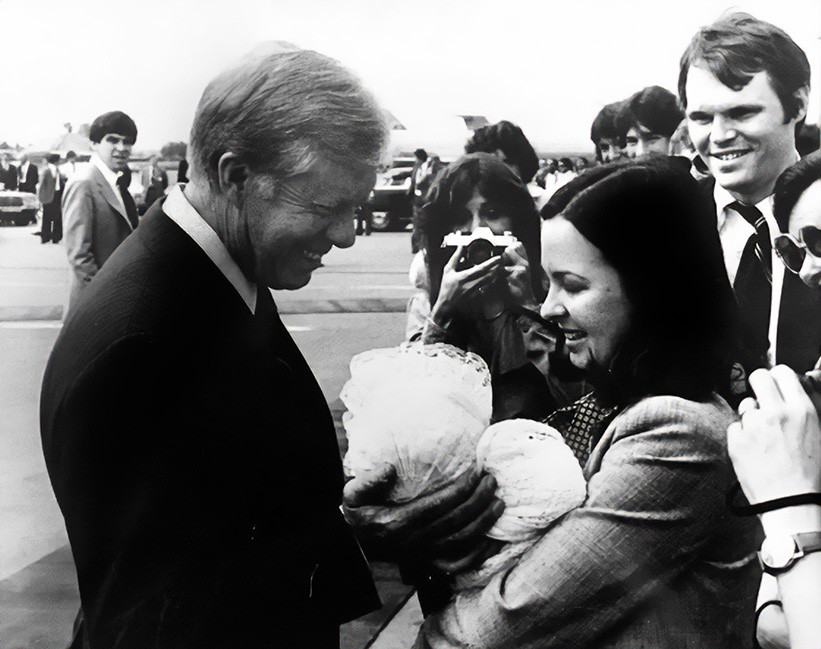

President Jimmy Carter greets FSO Anne Chermak and her 7-week-old daughter, Vanessa, on arrival in Belgrade, 1980.

Courtesy of Anne Chermak

President Carter made an official visit to Belgrade from June 24 to 25, 1980, a month after the death of longtime Yugoslav President Josip Broz Tito.

My husband, Mark Dillen, and I had been serving at the U.S. embassy in Belgrade as press and cultural officers since summer 1977. I gave birth to our first child, daughter Vanessa, on May 1, 1980, at the U.S. military hospital in Vicenza, Italy, and was still on maternity leave when President Carter’s visit to Belgrade was announced.

As the embassy’s deputy press officer, Mark was fully engaged with visit preparations. Meanwhile, I, as a first-time mom, was sleep-deprived and still adjusting to my newborn’s feeding schedule. I sent an SOS to my highly experienced mother, who had eight children of her own, to please come and help me. She took her very first flight, from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to Belgrade, arriving a couple of weeks before the big presidential visit.

Embassy staff were invited to greet President and Mrs. Carter upon their early morning arrival at the Belgrade airport, and my mother convinced me that we should go with 7-week-old Vanessa. We took a taxi from our home in Belgrade’s residential diplomatic colony, me cradling the baby in my arms—there were no seat belts or baby car seats back then—and took our place in line on the tarmac.

President and Mrs. Carter descended the stairs of Air Force One, and when he saw me standing there with a baby in my arms, all dressed up in a lacy dress and bonnet, the president made a beeline straight for us. Carter smiled broadly, asked how old my baby was, caressed her bonnet, and said to me in his Southern drawl, “You take good care o’ her now.”

As has been recounted by so many since his death at age 100, President Jimmy Carter was a good and decent man who cared deeply about humanity and devoted his life to making this world a better place. Thank you, President Carter!

Anne M. Chermak

Minister Counselor, retired

Denver, Colorado

When sharing or linking to FSJ articles online, which we welcome and encourage, please be sure to cite the magazine (The Foreign Service Journal) and the month and year of publication. Please check the permissions page for further details.