Toward a More “Geopolitically Driven” Relationship: Reflections of the U.S. Ambassador to Vietnam, 2011-2014

Moving beyond legacy war issues required building trust in the U.S. commitment to a strong, prosperous, and independent Vietnam.

BY DAVID B. SHEAR

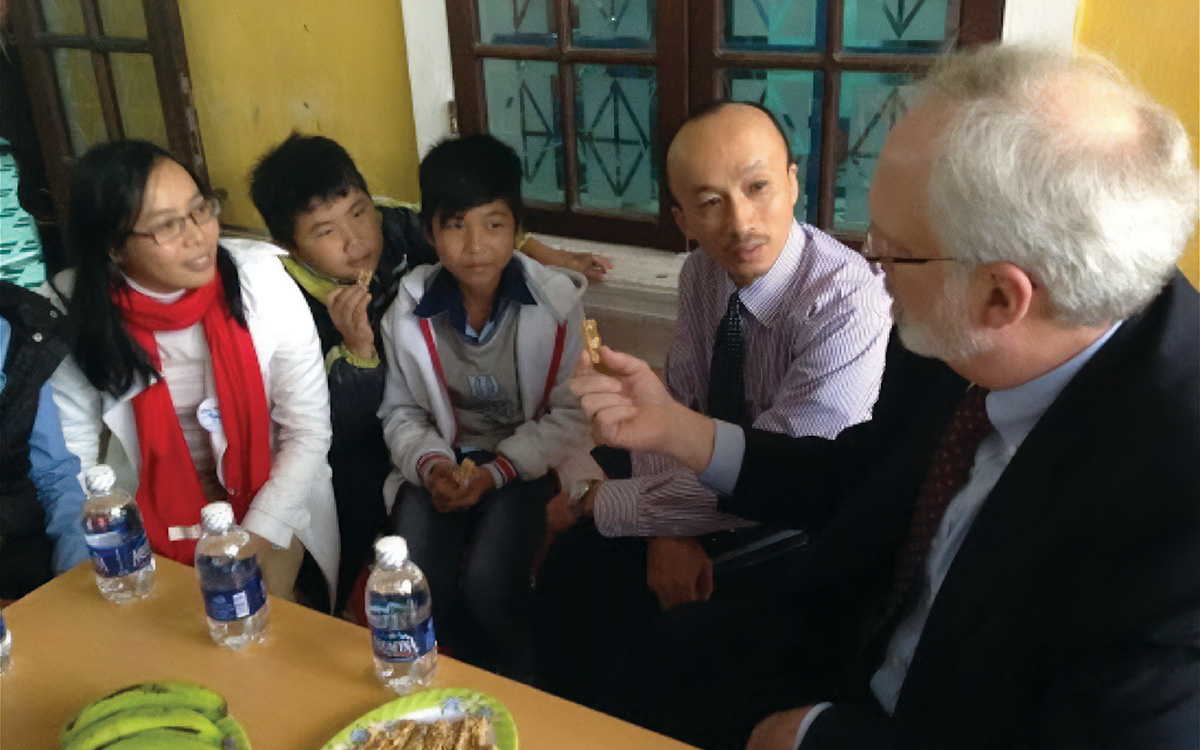

Ambassador David Shear chats with rescued child laborers at the Blue Dragon NGO headquarters in Quang Nam province with embassy interpreter Nguyen Duy Minh in March 2013.

Courtesy of David Shear

It became clear to me as I prepared to depart Washington for Hanoi in summer 2011 that Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and East Asia and the Pacific Assistant Secretary Kurt Campbell did not want me to just continue strengthening bilateral U.S.-Vietnam ties in the tradition of post-1995 ambassadors. They agreed with my conviction, developed during my 2008-2011 role as China desk director and China deputy assistant secretary, that the United States needed to establish a geopolitically driven relationship with the Vietnamese that would strengthen our position in the region vis-à-vis an increasingly assertive China.

The time was right for a geopolitical approach. Now that we were drawing down in Iraq and South Asia, President Barack Obama wanted to shift our attention to East Asia and to a rising China. He would not unveil our “rebalance” to the region until a November 2011 speech, but Secretary Clinton and Assistant Secretary Campbell had already begun laying the groundwork.

The Secretary had articulated an American strategic interest in the South China Sea in a widely reported July 2010 speech to the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Regional Forum in Hanoi. In fall 2010, we had participated in the East Asia Summit (EAS) as a guest, against the wishes of the Russians and the Chinese but with the strong support of Vietnam—that year’s ASEAN chair. We would join EAS formally the next year. So, building a regional role for the relationship driven by common U.S.-Vietnam geopolitical interests made strong sense, and my previous experience with Japan, China, and Southeast Asia had prepared me well for the task.

But what would establishing a more “geopolitically driven relationship” require? Vietnamese political elites have a saying: “If you get too close to the Americans, you lose the [Communist] Party; if you get too close to the Chinese, you lose the country.” My goal as ambassador was to help the Vietnamese walk the tightrope between the United States and China in a way that recognized local realities and suited American interests.

Those interests required that Vietnam participate effectively in a Southeast Asian balance of power that would maximize Hanoi’s room to maneuver, limit Chinese regional influence, and allow the United States and our allies to play the strongest possible role in an area of growing strategic and economic importance to us.

For a Strong and Independent Vietnam

Ambassador David Shear visits an orphanage in Bac Ninh province in March 2012.

Courtesy of David Shear

Common interests notwithstanding, an outright alliance with Vietnam was unlikely any time soon. The Chinese invaded Vietnam in 1979, partly in response to Hanoi’s conclusion of an alliance with Moscow, and I doubted that the Vietnamese leadership, many of whom had suffered through that war, would want to risk another such conflict. Moreover, China was geographically too close and offered too many economic opportunities for the Vietnamese to turn away from the big northern neighbor in favor of the U.S., a distant power with a reputation for bugging out.

“Why should we rely on the U.S. for our security,” a Vietnamese general exclaimed to me after the 2012 Scarborough Shoal incident, “when you’re unwilling to defend your ally the Philippines in the South China Sea?” So, a more incremental approach, within which I could manage growing Washington expectations, seemed wise.

We could still pursue a more vigorous diplomacy with Vietnam right away using all the tools of statecraft, not to establish a new alliance, but to buttress a balance of power that could assure our continued economic, diplomatic, and military access to the region. Vietnam’s size and population may have paled in comparison to the big powers with interests in the region, but this proud and growing middle power had agency, its leadership had pluck, and its people craved autonomy. Our Vietnamese interlocutors were astute observers of regional power relations and of the ebbs and flows of Chinese influence. Senior American officials liked talking to them.

At my first press conference as ambassador, I hit on a statement that would sum up our approach to Vietnam in words that would resonate with publics on both sides of the Pacific: “The United States seeks a strong, prosperous, and independent Vietnam that respects human rights and supports the rule of law.” Our two countries had significant common interests in free trade, freedom from coercion, and freedom of navigation in the South China Sea, and I hoped we could build a cooperative relationship on that basis.

To cooperate effectively with Hanoi, we had to build greater bilateral trust. This meant energetically continuing to address the legacies of war, including the search for American personnel missing in action (MIAs), the remediation of Agent Orange contamination at key sites, the removal of unexploded ordnance throughout the country, and assistance to those Vietnamese people with Agent Orange–related and other disabilities. I was proud to have watched over the construction of USAID’s project to incinerate soil heavily contaminated by Agent Orange at Da Nang Airport. I joined the congressional father of this program, Senator Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.), in Da Nang to open this facility in April 2014.

Ambassador David Shear (second from left) with (from left) Dr. Le Ke Son and Hill staffer Tim Rieser, both active in Agent Orange remediation, Michael DiGregorio from the Asia Foundation, and Charles Bailey from the Aspen Institute during Senator Patrick Leahy’s visit to Vietnam in April 2014.

Courtesy of David Shear

Legacy War Issues and Beyond

My predecessors had labored diligently on war legacy issues, including the search for MIAs. My Washington colleagues and I added a new task: removing the now outdated arms embargo on Vietnam. This would generate increased bilateral trust, build a closer military-to-military relationship, and help open a market for American military sales. I worked closely with my Washington counterparts to partially lift the embargo in late 2014, which we fully ended in 2016 while I was assistant secretary of Defense.

Building trust also required closer relations between the embassy and Vietnamese Communist Party headquarters. After all, the party ran the country, made all the important foreign policy decisions, and managed Vietnam’s day-to-day relations with China. Political Counselor Mark Lambert developed a useful relationship with the party’s Foreign Affairs Department. We sent party officials on International Visitor programs and briefed party officials generally on our approach to major developments in the region. Senior Vietnamese officials later informed me that this effort contributed directly to the decision to send then–Party General Secretary Nguyễn Phú Trọng to the U.S. in 2015.

Before departing for post, I was instructed to persuade the Vietnamese to join negotiations for the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) free trade agreement. That both countries would benefit from the TPP economically was obvious. It was also obvious that U.S. regional economic policy could bolster our geopolitical strategy not only by building Vietnam’s economic base but also by diversifying its international economic options.

The TPP would make it easier for Vietnam to avoid having to accommodate themselves completely to Beijing’s economic interests. It would also offer more opportunities for American firms looking to invest outside China. Our Economic Counselor Laura Stone made these points to our Vietnamese and American counterparts at every opportunity and smoothed the way for the U.S. Trade Representative’s talks with the Vietnamese. They joined the TPP negotiations in 2013.

On my 2011 introductory calls in Hanoi, I had told my hosts that both sides wanted Vietnamese TPP membership but that we had a problem: Congress would be less likely to support Vietnam’s participation in the agreement without demonstrable progress on human rights. Vietnam should not only agree to strong labor provisions within the TPP text itself but also show progress in other areas. My Vietnamese colleagues understood this and agreed to embark on an effort to explore with our embassy realistic steps the government could take.

We decided on a list that included, inter alia, Vietnam’s accession to the United Nations Convention Against Torture, registration of more unofficial house churches, and the release of political prisoners. By the time I left post, the Vietnamese had shown improvements in all these areas. (Our geopolitical and geoeconomic strategies diverged, and much of our leverage on human and labor rights evaporated with our departure from TPP in 2017, to my great disappointment and to the utter chagrin of our Vietnamese partners.)

Security Cooperation

Ambassador David Shear (fourth from right) accompanies an MIA recovery mission to Son La, northwest Vietnam, in July 2013.

Courtesy of David Shear

My able predecessor, Mike Michalak, had initiated negotiations on a military-to-military agreement during his tenure. In September 2011, a month after my arrival at post, the two sides concluded a Memorandum of Understanding on Advancing Bilateral Security Cooperation under which both sides pledged to upgrade collaboration in maritime security, military medicine, UN peacekeeping operations, humanitarian assistance and disaster relief, and exchanges between our defense universities.

We increased naval ship visits to Vietnam, including to Cam Ranh Bay, and intensified bilateral defense policy exchanges. We also added a civilian capacity building component to Vietnam’s maritime security program by agreeing to transfer six fast patrol boats to Vietnam’s Coast Guard. This was the precursor of the 2015 Maritime Security Initiative, a five-year, $450 million program designed to build capacity throughout the region that the Congress authorized during my tenure as assistant secretary of Defense.

“When the Chinese know the United States is engaged in the region, they treat us better,” a senior Vietnamese official once told me. During my tenure, the Vietnamese hosted visits by Secretaries of State Clinton and Kerry, the Secretaries of Defense, Treasury, Commerce, Health and Human Services, the Environmental Protection Agency administrator, and the Pacific commander, among others.

My mission also worked hard to bolster congressional support for an activist policy on Vietnam. Senators McCain (R-Ariz.), Leahy (D-Vt.), Carden (D-Md.), Corker (R-Tenn.), Whitehouse (D-R.I.), Ayotte (R-N.H.), and Lieberman (D-Conn.) and multiple congressmen visited Hanoi. As one might expect, Senator McCain was particularly supportive of our effort to take the relationship in a geopolitical direction. Increased exchanges like these paved the way for a successful 2013 visit to the U.S. by President Trương Tấn Sang, during which we announced the launch of a comprehensive partnership.

The Chinese provided the drama that marked the end of my already eventful tour. In early May 2014, the state-owned Chinese National Offshore Oil Company (CNOOC) moved an oil rig into disputed waters south of the Paracel Islands. This action sparked a stand-off between the two sides’ coast guard vessels, multiple sharply worded responses from Hanoi, and anti-Chinese rioting across Vietnam. Long-standing U.S. policy on territorial disputes prevented us from supporting the Vietnamese claim, but we did make our displeasure with the Chinese known and used the event to strengthen our ties to Vietnam’s national security community, particularly its coast guard. The Chinese action drew strong negative reactions throughout the region, and CNOOC withdrew the rig a month ahead of schedule, a modest victory for those opposed to Chinese adventurism in the South China Sea.

Any gains for U.S. interests in Vietnam during my tenure were the result of a team effort, also led by Deputy Chief of Mission Claire Pierangelo. A strong, collegial country team allowed us to use all the tools of statecraft in a systematic way. I tried to ensure that my team had everything it needed to do what American diplomats do best, which is to discover opportunities to advance U.S. interests and exploit them.

When sharing or linking to FSJ articles online, which we welcome and encourage, please be sure to cite the magazine (The Foreign Service Journal) and the month and year of publication. Please check the permissions page for further details.

Read More...

- “Foreign Policy and the Complexities of Corruption: The Case of South Vietnam” by Stephen Randolph, The Foreign Service Journal, June 2016

- “Beyond the Embargo: The Way Ahead for U.S.-Vietnam Strategic Relations” briefing by David B. Shear, Asia Society, July 2016

- “Machiavelli on How to Be a Good Diplomat” by David B. Shear, The Foreign Service Journal, November 2022