The Marginalization of Career Diplomats

New data on chiefs of mission suggests that the power and influence of career members of the U.S. Foreign Service are on the decline.

BY THOMAS SCHERER AND DAN SPOKOJNY

A new analysis suggests the extent of political-appointee control over U.S. foreign policy—and conversely, the decline of career-diplomat authority—is deeper than previously understood.

The ambassadors who lead our embassies overseas play a vital role in shaping and implementing U.S. foreign policy. While it has been common practice for decades for presidents to fill roughly 30 percent of chief-of-mission positions with political appointees, notably including donors, this ratio obscures a worrying decline of influence for career members of the U.S. Foreign Service.

According to a different measure—namely, the total gross domestic product (GDP) of host nations that have U.S. ambassadors who are members of the Foreign Service—the sway of career diplomats is vastly smaller.

This trend and its implications are important to keep in mind as we transition to a new administration in the coming months.

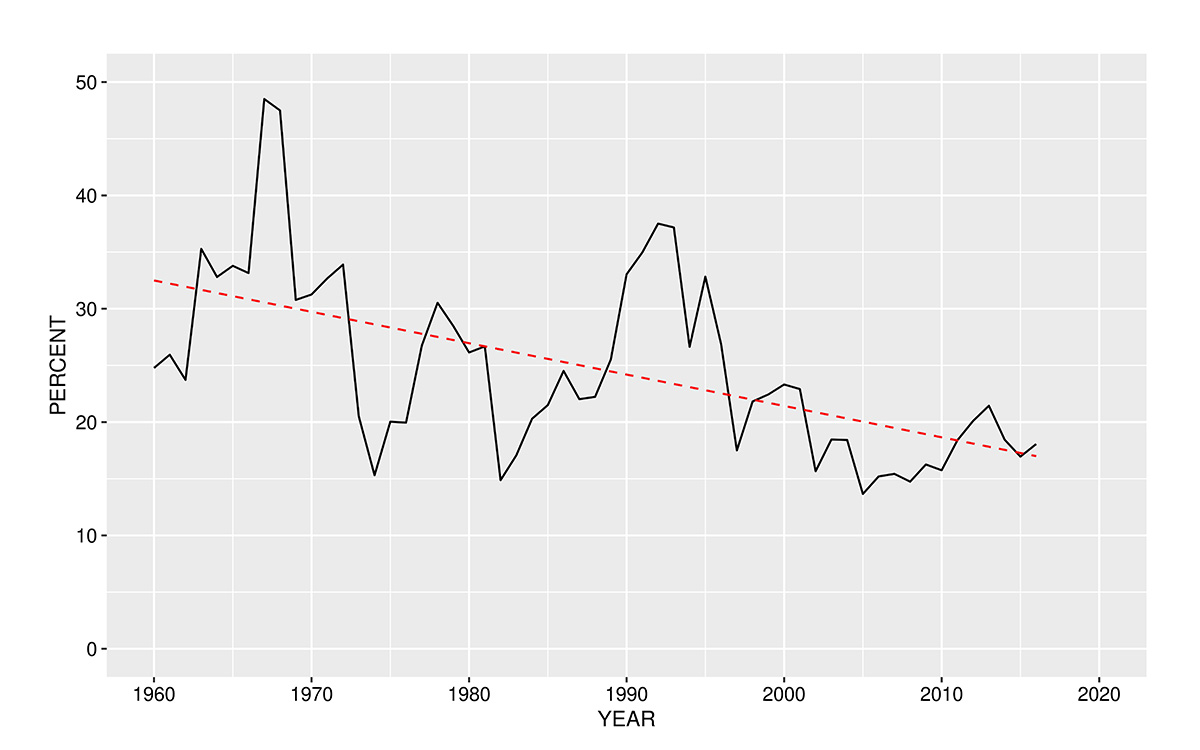

Figure 1: Aggregate GDP of Countries with Career FS U.S. Ambassadors.

Created by Thomas Scherer; data from Matt Malis

A Shrinking Sphere of Influence

A new analysis by fp21 shows that career FSOs have chief-of-mission authority in countries that, combined, are responsible for less than 20 percent of the world’s GDP, a portion that has steadily decreased in recent decades. In other words, if you add up the GDP of all nations in which politically appointed ambassadors lead U.S. embassies, it equals more than four-fifths of the world’s GDP (excluding the United States). This percentage does not account for influential multilateral ambassadorships also typically filled by political appointees, such as NATO, the United Nations, the European Union, and the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe.

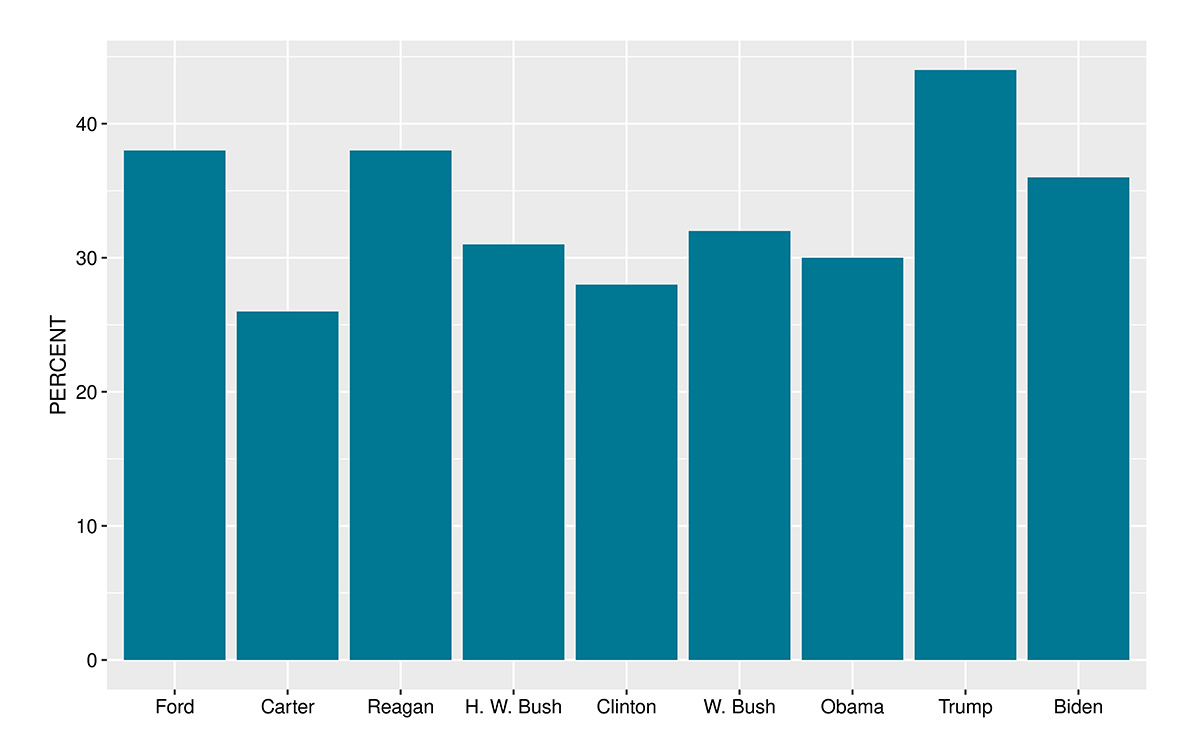

Data collected by scholar Matt Malis for the period from 1960 to 2015 shows no evidence that the trend of empowering political appointees over career members of the Foreign Service has significantly abated in recent years (see figure above). If anything, it may be on the rise. Data from the American Foreign Service Association suggests the Trump and Biden administrations have had the highest ratios of political appointees since Reagan (see figure below).

Host-country GDP is, of course, an imperfect measure of the influence of career diplomats. The collective influence of ambassadors depends on the complicated interaction between the power of the host government, the flow of current events, the strength of the individual ambassador, and more. Nevertheless, the trend identified here is noteworthy.

This trend and its implications are important to keep in mind as we transition to a new administration in the coming months.

Why It Matters

The choice of who leads our embassies has a measurable impact on the quality and capacity of our foreign policy institutions. Research has demonstrated that career officials, according to some metrics, are on average more effective leaders who oversee higher performance compared with their political-appointee counterparts. Career ambassadors, on average, have more of the desired qualifications, as defined by Congress, according to a study published in the Duke Law Journal in 2019.

The career diplomatic service was created to ensure presidents had access to nonpartisan experts who were insulated from political pressures so that they could speak truth to power. The State Department’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research, for instance, famously dissented against the incorrect claim that Saddam Hussein’s Iraq possessed weapons of mass destruction.

Some fear that the reliance on political appointees at the helm of U.S. embassies risks returning our country to the pre-Pendleton Act, pre-Rogers Act spoils system. The law governing diplomacy, the Foreign Service Act of 1980, directs that “positions as chief of mission should normally be accorded to career members of the Service, though circumstances will warrant appointments from time to time of qualfied individuals who are not career members of the Service.”

Worryingly, many talented young foreign policy aspirants no longer believe that joining the career Foreign Service is the most viable pathway to influence in U.S. foreign policy. The sacrifices of public service loom larger when one’s influence wanes. Morale inside the institution suffers.

Figure 2: Political-Appointee Ambassadors by Administration.

Created by Thomas Scherer; data from AFSA

What Career Diplomats Can Do

The next president of the United States, whether it be Kamala Harris or Donald Trump, will have experience in the White House. We hope that experience has taught them that the successful execution of their goals will depend, at least in part, on the career officials who serve at the cutting edge of U.S. foreign policy.

Yet, we also believe that career diplomats deserve some of the blame for their own diminishment (this is said with utmost respect; one of us is a proud former career diplomat). Career diplomats have done an ineffective job proving to presidents that their skills are superior and sufficiently differentiated from political appointees.

The definition of a profession is “a paid occupation, especially one that involves prolonged training and a formal qualification.” One must question whether the U.S. Foreign Service rises to this standard. Precious little intellectual capital has been produced from within the institution to advance meaningful professional standards or doctrine. The Foreign Service’s muted response to the State Department’s new Core Curriculum for diplomacy is a case in point. One might have expected the institution to leap at the opportunity to set a high bar for itself.

We also believe that career diplomats deserve some of the blame for their own diminishment.

The Foreign Service’s ethos of self-assuredness and habit of eschewing rigorous training not only jeopardizes the quality of U.S. foreign policy but is also politically ineffective. The evidence presented here suggests the influence of the Foreign Service has been on a steady decline for decades. We are particularly disappointed when Foreign Service luminaries claim that foreign policy is “an art, not a science.” It is not merely anachronistic; it is an invitation for outsiders to join diplomacy’s ranks with little formal training.

Most observers would agree that there is a role for both political appointees and highly professionalized career officials in leading the State Department. We believe that the next president can identify a more reasonable balance between career and political appointees. Ultimately, what matters is the strength of our national security and the United States’ ability to contribute to a more just and stable world.

The apparent marginalization of career diplomats is good for neither.

When sharing or linking to FSJ articles online, which we welcome and encourage, please be sure to cite the magazine (The Foreign Service Journal) and the month and year of publication. Please check the permissions page for further details.

Read More...

- “American Needs a Professional Foreign Service” by Charles A. Ray, The Foreign Service Journal, July-August 2015

- “Why U.S. Ambassadors Should Be Career Professionals” by Edward L. Peck, The Foreign Service Journal, January-February 2017

- “Career Diplomats Matter” by Julie Nutter, The Foreign Service Journal, May 2019

- “Toward a More Modern Foreign Service: Next Steps” by Marc Grossman and Marcie Ries, The Foreign Service Journal, March 2023