J. Rives Childs in Wartime Tangier

Despite the wealth of material generated by and about U.S. diplomat J. Rives Childs, he remains an enigma a quarter-century after his death.

BY GERALD LOFTUS

J. Rives Childs’ official portrait, which hangs in the legation next to the text of Renée Reichmann’s Holocaust letter.

Courtesy of the Tangier Legation

On July 16, 1987, the New York Times noted the passing of J. Rives Childs (1893-1987), a “former American diplomat and authority on Casanova.”

Childs had led many lives: volunteer ambulance driver à la Hemingway and U.S. Army cryptographer in France during World War I (he later received the Medal of Freedom for cracking German codes); postwar White House correspondent; American Relief Administration official (one of “Hoover’s Boys”) in the famine-stricken USSR of the 1920s; and a Foreign Service officer whose 30-year career culminated with ambassadorships to Saudi Arabia and Ethiopia after World War II.

He also wrote 14 books, ranging from definitive studies of Casanova and French writers of the 18th century (some written in French) to several works touching on his Foreign Service career. His final memoir, Let the Credit Go (1983), recounts his tenure as chargé d’affaires at the American Legation in Tangier, Morocco, between 1941 and 1945.

Despite the wealth of material generated by and about Childs, he remains an enigma. Was it just luck that he came unscathed through the McCarthy-era witch hunts despite some unconventional views on the Soviet Union? Just how effective a diplomat was a man some called an “insufferable prig” for driving his staff up the wall—including agents from the wartime Office of Strategic Services who were just trying to do their job?

And is Childs an unsung hero of the Holocaust, whose name belongs among the “righteous gentiles” at Israel’s Yad Vashem memorial? Or all of the above?

Franco’s Spain and Petain’s France Meet in Morocco

For sheer complexity and strategic importance, Childs’ service in Tangier as chargé d’affaires (1941-1945) overshadows his later assignments as ambassador.

Though he resided at the American legation in the city’s International Zone, Childs was accredited to Morocco, which was divided into French and Spanish protectorates. The U.S. had never recognized the Spanish zone, and the situation was further complicated when the forces of General Francisco Franco, recently victorious in the Spanish Civil War, occupied the International Zone after France fell to German forces in June 1940.

For sheer complexity and strategic importance, Childs’ service in World War II-era Tangier as chargé d’affaires overshadows his later ambassadorships.

The U.S. continued to recognize the Petain government in Vichy, and American policy was to cultivate relations with Vichy representatives in North Africa. Childs applied himself energetically to that task, cultivating officials favorable to the Allied cause and probing French and Spanish officials about their attitudes on a hypothetical Allied landing.

In particular, would Franco abandon his official neutrality and allow German forces to sweep down from Spain and through Morocco once American troops landed (as they did in November 1942’s Operation Torch)? (Franco did maintain Spanish neutrality, angering Adolf Hitler.)

These concerns were shared by the new clandestine service set up in the wake of Pearl Harbor, the Office of Strategic Services. This precursor to the CIA chose the American legation in Tangier as its headquarters for Mediterranean operations, and recruited a Harvard anthropologist, Carleton Coon, who was given diplomatic cover as a vice consul. Coon’s anthropological fieldwork in the northern Moroccan Rif Mountains in the 1920s and 1930s gave him an entrée with the Berber tribes who had rebelled against Spanish occupation.

The OSS plan was to furnish financial support and weapons so the Berbers would be ready to rise up in rebellion should Franco join the Axis and threaten the Allies (which, happily, he never did). Vice Consul Coon invented fanciful code names for his chief Moroccan contacts like “Tassels” and “Strings.” He later described his cloak-and-dagger work in North Africa Story, an entertaining compilation of his wartime reports.

Coon’s exploits did not amuse Childs, however. Though he didn’t name Coon, the chargé later wrote that one of his vice consuls had harbored delusions of becoming “a second Lawrence of Arabia.”

For his part, Coon paints a damning picture of Childs as so out of touch about the nature of clandestine work that he had the OSS communication operation moved out of the legation because the tapping of the telegraph kept his wife awake at night. Retired Ambassador Carleton Coon Jr. recalls: “This appeared treasonable to my father, and after I started on my own diplomatic career, my father swore he would never allow his son to serve under ‘that SOB’.”

Whether this was “treasonable” conduct or just extreme micromanagement is a matter of opinion. What is less debatable is that many of Childs’ colleagues saw him as priggish. For instance, he proudly recounted his success in prohibiting female American dependents from wearing slacks and shorts within the residential compound in Addis Ababa, his last diplomatic posting, in the early 1950s. When the women protested this vestige of Puritanism, Childs threatened to have any offenders and their husbands transferred out of Ethiopia.

One of Childs’ vice consuls in Morocco, Carleton Coon, portrays him as woefully out of touch about the nature of clandestine work.

Fascist Visas Save Jewish Lives

The cover of the invitation to Childs’ farewell dinner in June 1945.

Courtesy of the Tangier Legation

During his time in Spanish-occupied Tangier of the 1940s, Chargé Childs had initially approached the Spanish authorities with circumspection, assuming that High Commissioner General Luis Orgaz was a Franco fascist. But working contacts fostered warmer relations, which would lead to an important humanitarian action.

Tangier, like the Casablanca depicted in the film of that title, was an important hub for refugees fleeing both the war and the Holocaust. Renée Reichmann, herself a refugee from Hungary, was a key figure in relief efforts from Tangier, and was affiliated with the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee.

Reichmann’s efforts in sending tons of food parcels to occupied Europe were herculean, and she even performed the unimaginable: a trip back through fascist Europe to Hungary in 1942 to see her parents for what proved to be the last time. By early 1944, the Jewish community of Hungary was targeted for the Final Solution, and her focus shifted from relief to rescue.

She approached Childs to enlist his help in extricating hundreds of Jews in Budapest from the clutches of the Nazis. Reichmann’s request came just after the Roosevelt administration created the War Refugee Board, a belated attempt to intervene on behalf of Jews and other threatened populations. Childs was therefore able to add official U.S. government weight to what was initially a personal, humanitarian gesture.

It turns out that Spanish High Commissioner General Orgaz was not the fascist that Childs had assumed him to be. He issued several tranches of visas for Tangier, which was sufficient for the Nazis to consider the threatened Jews to be protected by a friendly power. On the eve of Childs’ departure from Tangier in June 1945, Reichmann wrote him to express thanks “for your extremely noble and generous assistance in the affair of the entry visas for Tangier. ... Thus, 1,200 innocent souls owe their survival to Your Excellency.”

At the Tangier American Legation’s museum, we display the full text of Reichmann’s letter, and note the fact that J. Rives Childs kept the letter in his pocket for years afterwards. For this action, worthy of Raoul Wallenberg and other World War II diplomats who saved Jews by the thousand, Childs—as in the title of his autobiography—“let the credit go” to Reichmann for proposing the action and to Orgaz for issuing the visas.

Childs, as in the title of his autobiography, “let the credit go” to others for saving 1,200 Jews in Budapest from the clutches of the Nazis.

An Arabist, but Not an Anti-Semite

The operation, however, clearly left its mark on the seemingly stiff diplomat. Responding to Reichmann, he wrote: “I do not know of any work which I have done in my whole career which has given me greater personal satisfaction than the efforts made on behalf of these friendless persons.”

At the same time, Childs’ motivation for keeping Reichmann’s letter went beyond sentiment. In his mind, it refuted any potential accusations that he was sympathetic to the cause of anti-Semitism.

His sensitivity to such charges presumably grew over the course of a succession of assignments in the Arab world. He served as consul in Jerusalem during the 1920s and as a desk officer for the Palestine Mandate and mid-level diplomat in Cairo in the 1930s, followed by assignments to Tangier and Jeddah in the 1940s.

“There is not the least doubt in my mind,” he commented in reflecting on his 30 years’ experience in the Middle East, “that so long as our unconditional support of Israel continues, there will be no peace in that area.” In 1952, in what he called his “swan song,” he sent a telegram responding to a question about Arab support for U.S. policy as follows: “United States support of Israel has undermined the confidence and trust which we once enjoyed in the Arab world.” He retired from the Foreign Service that same year.

Anti-Zionism, of course, does not equate to anti-Semitism, and there is no evidence at all that Childs was anti-Semitic. But we don’t have to take his own word for that. In his book, The Reichmanns, Anthony Bianco describes that family’s efforts to have Childs recognized at Yad Vashem as a “righteous gentile.”

The Reichmanns launched that campaign even though they understood full well how unlikely they were to succeed. Not only was Israel loath to give any credit to Franco’s Spain for issuing the Tangier visas, but Childs’ years spent conducting diplomacy in the Middle East were enough to disqualify him from such recognition. It also did not help that Robert Satloff, who devotes his book, Among the Righteous, to the search for “Arab Schindlers” in North Africa in the 1940s, makes no mention of the American diplomat’s role in saving 1,200 Jews.

Is Childs an unsung hero of the Holocaust, whose name belongs among the “righteous gentiles” at Israel’s Yad Vashem memorial?

“Unduly Interested” in Soviet Russia?

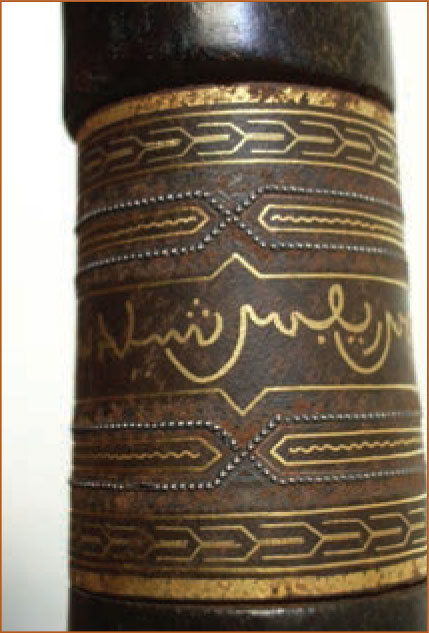

The hilt of Childs’ sword-cane, a gift from legation staff, was inscribed with his name in Arabic.

Courtesy of the Tangier Legation

Childs had cause to fear political attacks on another front, as well. As early as 1931, Childs recalled, “I received a letter from the State Department saying that attention had been drawn to me for being unduly interested in Soviet Russia.”

Presumably this criticism was based on the fact that Childs had spent two years in the Soviet Union as a relief worker a decade earlier, and had married a Russian woman. Even so, Childs always felt that his interest in the USSR was justified on an intellectual basis, as well as for personal reasons. At one point he commented: “One of the quirks of [the] American character is the pathological reaction, bordering on mental disorder, toward anything touching the Russian Revolution or communism.”

In 1939, Childs learned that he had been recommended for promotion, but the move was later rescinded. He never learned exactly why, but assumed it was because “I was believed to entertain unorthodox opinions about Soviet Russia.” Of course, he went on to become chargé in Tangier and a two-time ambassador, so the episode was clearly not a career-ender.

Jamie Cockfield, editor of Childs’ memoir of the Russian famine years, The Black Lebeda, saw him as a “limousine socialist.” Perhaps so. But in his intellectual embrace of Casanova and other 18th-century writers, Childs primarily seems a man from a bygone age, one who decried the end of the ancien régime in the wake of World War I.

Writing in 1983, he saw many of the modern world’s troubles—World War II, the Arab-Israeli standoff—as rooted in that traumatic war in the trenches. “The end is not yet in sight, nor is it ever likely to be.”

J. Rives Childs may well have been a flawed hero. But then again, so was Oskar Schindler.