Love in Tiflis, Death in Tehran: The Tragedy of Alexander Sergeyevich Griboyedov

This story of power politics, warfare and diplomacy in 19th-century Iran and the Caucasus is a rich slice of history. It is also a cautionary tale that transcends its time and place.

A monument to Alexander Sergeyevich Griboyedov in St. Petersburg.

Galexandrova [CC by SA4.0] / Wikimedia Commons

BY JOHN LIMBERT

On June 11, 1829, the young Russian poet Alexander Pushkin was traveling through the Caucasus Mountains to meet his brother, who was serving on the Turkish front. At Besobdal, on the Armenian- Georgian border, he describes the following scene:

…Having rested a few minutes, I set out again and saw opposite me on the high bank of the river the fortress of Gergery. Three streams plunged down the high bank, plunging noisily. I crossed the river. Two oxen harnessed to a cart were descending the steep road. Some Georgians were accompanying the cart.

“Where do you come from?” I asked them.

“From Teheran.”

“What do you have on your cart?”

“Girboyed.”

This was the body of the slain Griboyedov, which they were taking to Tiflis.

This grim encounter in the mountains of northern Armenia (recorded in Pushkin’s A Journey and quoted in Laurence Kelly’s Diplomacy and Murder in Tehran) took place six months after the murder of the young Russian emissary to Persia, Alexander Sergeyevich Griboyedov. The diplomat had been in Tehran only a month in 1828 when a mob stormed the Russian mission, murdering all of the Russians there except the first secretary, Ivan Mal’tzov, who managed to escape. The tragedy put an end to the remarkable career of a Russian intellectual, diplomat, poet and playwright. It is also a rich source of lessons and insights for contemporary diplomats and students of international affairs.

Griboyedov had been closely involved with the power politics, warfare and diplomacy that accompanied the Czarist Empire’s expansion into the southern Caucasus and its humiliation of the feeble Qajar dynasty of Persia. He was one of the negotiators who concluded the famous 1828 Treaty of Turkmanchai between Russia and Persia, a one-sided agreement that Iranians have long viewed as the symbol of their victimization and exploitation by foreigners.

The young diplomat’s fate can be traced to shortsighted Russian nationalism that insisted on imposing the harshest and most humiliating conditions on the Qajar rulers; simmering Iranian resentments that took only a small spark to become murderous mob violence; personal grudges by individuals who found a chance to insult religious feelings and the honor of high-ranking Iranians; as well as his own obliviousness to the explosive situation in Tehran, the provocative actions of his underlings, the power of insults to Persian honor and the extent to which the people of Tehran sought to avenge their country’s debasement.

Further, Griboyedov’s blind obedience to his instructions to enforce every provision of Turkmanchai led him to reject all lastminute offers of compromise, which would very likely have saved him and his mission members.

This drawing by Hippolyte Bellangé depicts Crown Prince Abbas Mirza (1789-1833), the son of Fath-Ali Shah, reviewing his infantry. Intelligent and possessed of some literary taste, he was an early modernizer of Persia’s armed forces and institutions. Yet with Abbas Mirza as the military commander of the Persian forces, Iran lost all of its territories in the Caucasus to Russia in conformity with the 1813 Treaty of Gulistan and the 1828 Treaty of Turkmanchai, following the outcomes of the 1804–1813 and 1826–1828 wars.

Wikimedia Commons / repository.library.brown.edu

First Assignment to Persia

This miniature portrait of Fath-Ali Shah Qajar (1772-1834), the second Qajar king of Persia, was painted by Ahmad in 1811. It is part of the David Collection in Copenhagen.

Wikimedia Commons / www.davidmus.dk

Born in 1795 into a family of minor Russian nobility, Griboyedov joined the Russian diplomatic service in 1817 after four years of military service. His early service in St. Petersburg seemed to include mostly parties, gambling, flirtations and debts. Involvement in a duel between colleagues led to his semi-exile to Persia in 1818 as deputy to S.N. Mazarovich, emissary to the court of Fath-Ali Shah Qajar (1797-1834).

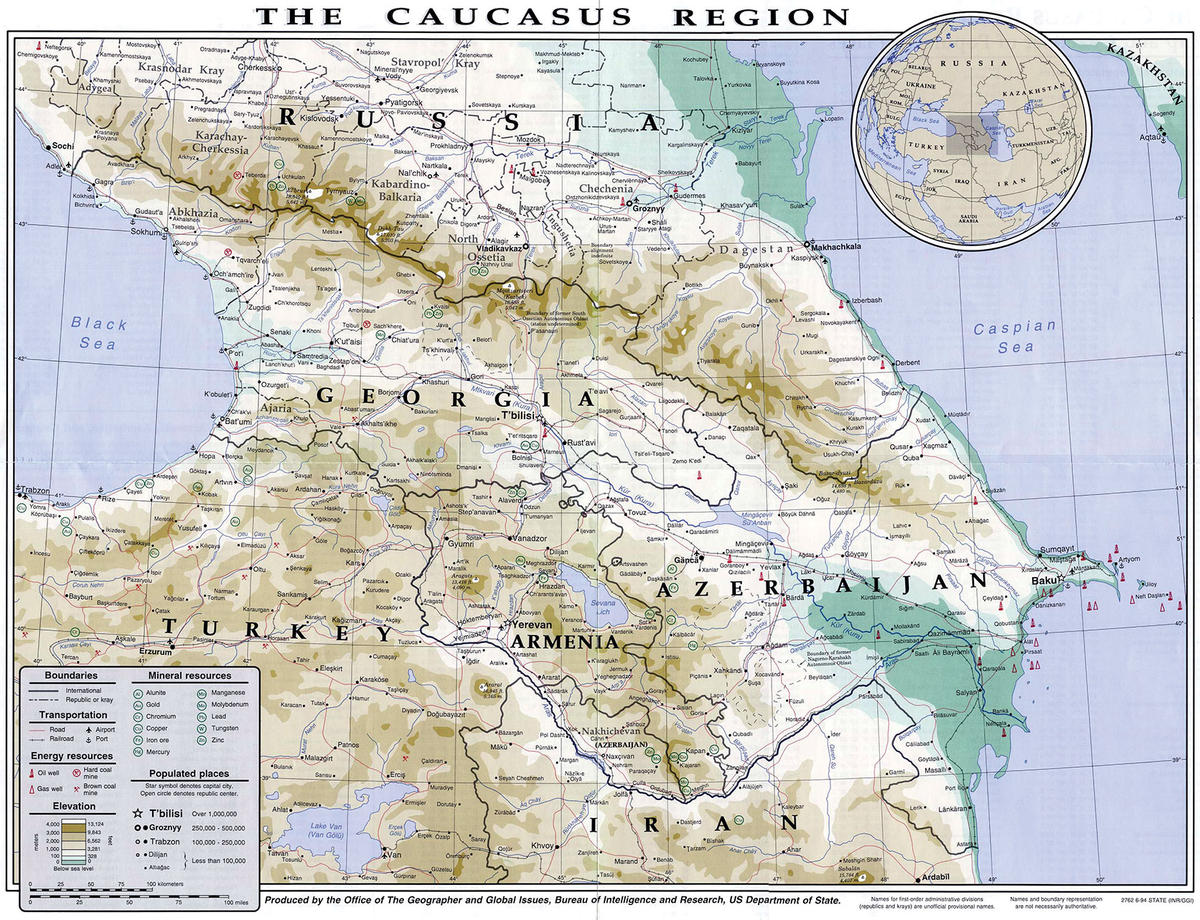

It had been five years since the Treaty of Gulistan ended the first Russo-Persian war. The two unequal empires came into direct conflict early in the nineteenth century, following Russia’s annexation of the ancient Orthodox Christian kingdom of Georgia in 1801. Along with the Ottoman Empire, Russia and Persia vied for influence over the semi-independent khanates of the southern Caucasus in the regions of Karabakh, Nakhchivan, Derbent (Darband), Talesh and Shirvan. The war that broke out between Russians and Persians in 1804 ended with military disaster in 1813. Under the Treaty of Gulistan, Persia recognized Russian control of most of today’s Georgia and the Republic of Azerbaijan. North of the Aras (Araxes) River, the Persians retained only the regions of Yerevan (in modern Armenia) and Nakhchivan (today an Azeri enclave inside Armenian territory).

Mazarovich’s mission was to deal with the aftermath of Gulistan, including the return of Russian deserters, unresolved border issues and Russian commercial activities in Persia. When the mission reached Tiflis (today’s Tbilisi) in October 1818, Griboyedov met the aggressive Russian viceroy and military commander of the Caucasus, Alexis Petrovich Yermolov, who was to be his protector and patron until the former’s dismissal in 1827. Yermolov was known for his brutality against the Muslim population of the Caucasus and for his provocations against the Persians in the disputed border areas— incidents that would goad the Qajar rulers into unwisely renewing war against the Russians in 1825.

Still a headstrong young man, Griboyedov fought a duel while in Tiflis. The incident was smoothed over thanks to the indulgence of both Yermolov and Griboyedov’s civilian boss, Mazarovich, and the mission travelled on to Tabriz in early 1819. Ruling there as governor was the 26-year-old Qajar Crown Prince Abbas Mirza, who received the Russian mission with respect. Mazarovich observed reciprocal diplomatic courtesies toward his hosts in an effort to undo the damage done by the tactless Yermolov.

Griboyedev’s first sojourn in Persia (1819-1821) was less than a personal or diplomatic triumph. Always the Russian nationalist, he resented serving under the Catholic and non-Russian Mazarovich. While Mazarovich mostly remained at the shah’s court in Tehran and on the cooler plains of Soltaniyeh, Griboyedov remained mostly in Tabriz, where a monastic lifestyle did not suit the young bachelor. His main accomplishment was to escort a group of several hundred Russian deserters from Tabriz to Tiflis, where, despite reassurances, they received a less than friendly welcome. While in Tabriz he occupied himself with studying Persian, attempts at commercial ventures and work on his most famous composition, the verse comedy “Woe from Wit.”

In 1821 he succeeded in getting himself attached to Yermolov’s staff in Tiflis, and was able to leave Tabriz. The years 1823 to 1825 found him on extended leave in St. Petersburg enjoying the capital’s literary circles and completing his play. In late 1825 he returned to Tiflis and Yermolov’s staff, but the failed “Decembrist” revolt of that year led to his arrest and forced return to St. Petersburg. By June 1826 an investigation had cleared him of complicity in the uprising. Despite the fact that a new war had broken out between Russia and Persia, he made a leisurely return to his post on Yermolov’s staff in Tiflis, arriving there late in the year.

His fortunes improved when the new czar, Nicholas I, replaced Yermolov with his deputy, Ivan Paskievich, in March 1827. Paskievich was related to Griboyedov by marriage and made the young official his close adviser on matters related to the Persians and the peoples of the Caucasus. Paskievich combined military victories against Abbas Mirza and the weak Qajar armies with diplomatic success, thanks to strategic alliances with the autonomous Muslim rulers of the Caucasus.

Negotiating Turkmanchai

Following a string of Persian defeats, Abbas Mirza approached Paskievich in the summer of 1827 seeking an armistice. The latter sent Griboyedov to lead the Russian negotiating team at Tabriz, although what happened there was less a negotiation than a series of ultimatums from the victorious Russians to the defeated Persians. Russia demanded the cession of Yerevan and Nakhchevan provinces to Russia and reimbursement for the full cost of the war plus a substantial indemnity. The meetings ended inconclusively, and Griboyedov predicted that the Persians would accept the Russian terms only after the fall of Yerevan. By October 1827, the Russian armies had not only captured Yerevan, but had occupied Tabriz and Ardabil as Persian resistance collapsed.

In February 1828 Persian and Russian envoys, including Griboyedov, concluded what became famous as the Treaty of Turkmanchai. Its provisions were:

• Cession to Russia of territory north of the Aras River, including Yerevan and Nakhchevan. Establishment of the Talesh frontier (near Astara on the Caspian).

• Payment of 20 million silver rubles to Russia in reparations. Russian troops would gradually withdraw from Iranian Azerbaijan as installments were paid.

• Russia to have exclusive right of trade and navigation (including maintaining a navy) on the Caspian Sea.

• Persia to remain neutral in case of war between Russia and Turkey.

• Free emigration of Persian citizens, Armenians in particular, who wished to settle in new Russian territory.

• Russia to recognize Abbas Mirza as heir to the Qajar throne.

• Russia to open consulates to protect her merchants in Persia, who were subject only to Russian law.

This one-sided treaty was a humiliation that in the Iranian political vocabulary became the Iranian Munich, synonymous with appeasement and surrender. The indemnity bankrupted an already depleted Qajar treasury; the loss of wealthy provinces in the southern Caucasus brought foreign forces to the border of Azerbaijan, Iran’s richest and most strategic region. In the longer term, the treaty gave Russia a voice in Persia’s royal succession and gave foreign private citizens, through the hated “capitulations,” immunity from local law. In the short term, the provisions for repatriating Armenians were to prove deadly for Griboyedov and his colleagues.

If Griboyedov understood the implications of this treaty, there is no sign that he cared. He received a hero’s welcome when he delivered it to St. Petersburg in March 1828. Czar Nicholas I gave him a decoration and a cash reward and appointed him resident minister plenipotentiary—one step below ambassador—to the Persian court.

Last Mission to Tehran

Princess Nina Chavchavadze

Wikimedia Commons

Alexis Petrovich Yermolov, by E.A. Dimitriev Mamonov

Wikimedia Commons / Shakko

Ivan Paskievich

Wikimedia Commons / Friedrich Randell

By July 1828 Griboyedov was back in Tiflis. A month later he married the 16-year-old Georgian princess, Nina Chavchavadze, and in the autumn the envoy’s entourage, with the pregnant Nina, made the difficult trip to Tabriz. There he had the unpleasant task of extracting installments of the indemnity from Abbas Mirza, whose father, the shah, refused to help. Finally, leaving Nina in the care of the English consul and his wife, Griboyedov traveled in hard winter weather to Tehran, arriving on Dec. 30.

He quickly completed his two missions. He presented his credentials to Fath-Ali Shah and, at a second meeting with the shah, presented a ratified copy of the Treaty of Turkmanchai. Although both sides kept up diplomatic appearances, the mood in Tehran was ugly, as people digested the extent of the mortification inflicted on Persia. Griboyedov, apparently unaware of the simmering resentment, played the role of conquerors’ envoy and thought only of leaving Tehran as soon as possible to rejoin his wife at a country house near Tiflis. He planned to depart on Jan. 31, 1829.

In late January a distracted Griboyedov was caught by surprise when a seemingly trivial incident involving Armenians became a firestorm. One of the shah’s eunuchs, an Armenian convert to Islam named Mirza Yakub, sought asylum at the Russian mission. The desertion of such an important person, with access to intimate matters at the shah’s court, was a major embarrassment to the Persians. Griboyedov could not ignore his role as protector of Iranian- Armenians, but he failed to recognize the sensitivities in a case involving both the fugitive’s religious conversion and his access to private matters of the Qajar court.

Things took a turn for the worse when Mirza Yakub, abetted by Griboyedov’s Georgian quartermaster, Rustem-Bek, sought other Armenian converts for Russian protection. Both men’s motive seems to have been a desire to continue humiliating the Persians and rubbing their faces in the recent defeat. The pair found two female candidates for protection in the harem of Allahyar Khan, a Persian nobleman who had encouraged the original (and disastrous) attacks on Russia and who bore personal grudges against both Griboyedev and Rustem-Bek. After some hesitation, the two women took asylum in the Russian embassy. Despite attempts by both Russians and Persians to find a solution, Mirza Yakub refused to back down and the seemingly oblivious Griboyedov, although angry at Rustem- Bek’s troublemaking, insisted on his right to carry out the letter of the peace treaty, including keeping Allahyar Khan’s women at the embassy.

On Jan. 29, 1829, Rustem-Bek lit the last fire when he ordered the two women taken to a bathhouse near the embassy. The message was: they are being prepared for marriage, yet another insult to the honor of their Iranian Muslim husband, Allahyar Khan. Throughout the day reports spread in the city that Mirza Yakub had betrayed Islam, and that the Russians were not only holding two Muslim women taken from their husband but were making them convert to Christianity. The next morning a crowd gathered at the city’s main mosque, where preachers ordered the people to seize Mirza Yakub and rescue the two women. In the ensuing clash at the embassy—the Persian guards had disappeared— Mirza Yakub, a Cossack guard, several servants and several attackers were killed. Allahyar Khan’s men seized the two women.

Angered by the deaths of their compatriots, the mob reappeared later in the day. When a Cossack guard disobeyed Griboyedov’s orders and killed an attacker, the mob stormed the building and murdered every Russian they found there—including Griboyedov. Persian authorities were helpless against the mob; when the governor of Tehran attempted to disperse them, they told him: “Go pander your wives to the Russians.” For four days, the shah and his court remained locked in their palaces. Order was finally restored when the insurrection ran out of steam.

The Aftermath

The Russians’ reaction to the murders was restrained. In hindsight, it is clear they had little desire to jeopardize the advantageous terms of Turkmanchai or to prolong their military occupation of Persian territory while they were engaged in a war with the Ottomans in both Europe and Asia. Viceroy Paskievich and Foreign Minister Karl Vasilyevich Nesselrode found it convenient to accept the abject apologies of the shah and crown prince and their explanations that they had nothing to do with the outburst of the Tehran mob.

The Qajars—who seemed unable either to conduct a war or control their own population—sent Prince Khosrow Mirza, the son of Crown Prince Abbas Mirza, on a mission to St. Petersburg with a letter of apology from Fath-Ali Shah. Perhaps more effective in placating the czar were gifts from the shah—essentially Griboyedov’s blood money—including an enormous diamond looted from Delhi a century earlier. For his part, Czar Nicholas announced he was ready to forget the matter and even forgave the last installment of war indemnity, for the sake of which Griboyedov had alienated so many of his Persian hosts.

Griboyedov’s widow, Nina, remained at Tabriz where no one would tell her of her husband’s fate. In her last trimester of pregnancy, she returned to Tiflis and there heard the tragic news. Overwhelmed by grief, she lost her child. She never remarried and died of cholera in 1857. She was buried beside her husband at the Monastery of St. David near Tiflis. She had had the following words engraved on his monument: “Your spirit and your works remain eternally in the memory of Russians: Why did my love for thee outlive thee?”

The final tragic irony of Griboyedov’s diplomatic career is that in May 1828, when he presented his foreign ministry bosses in St. Petersburg recommendations for future Russian policy toward Persia, he had proposed a course of mildness and leniency and of flexibility in the matter of the indemnity. When his superiors rejected his proposals, Griboyedov did not follow his own advice and best instincts. Instead, as a Russian nationalist and obedient civil servant, he had no hesitation in carrying out the harsher policy his superiors ordered—a policy they softened only after he and his colleagues were murdered.