Helping Europe Help Itself: The Marshall Plan

On the eve of its 70th anniversary, the Marshall Plan remains one of the most successful foreign policy initiatives in U.S. history and a model of effective diplomacy.

BY AMY GARRETT

From left to right, President Harry S Truman, General George Marshall, Paul Hoffman and Averell Harriman in the Oval Office discussing the Marshall Plan, Nov. 29, 1948.

Abbie Rowe / Wikimedia Commons

The European Recovery Program, better known as the Marshall Plan, is often cited as one of the most effective U.S. foreign policies of modern times. When there is a natural disaster, a humanitarian crisis or a national struggle with a social or economic challenge that demands immediate attention, American politicians and opinion-makers often call for “another Marshall Plan.”

Announced on June 5, 1947, by Secretary of State George C. Marshall and signed into law by President Harry Truman on April 3, 1948, this famous initiative—which offered assistance to help European nations recover from the massive infrastructural and economic damage wrought by World War II—will soon celebrate its 70th anniversary. Yet even though it is widely considered successful today, many Americans were highly skeptical in the late 1940s that spending billions of dollars to help pull Western Europe out of economic distress was in the U.S. interest.

Formulating the Marshall Plan

In contrast with the massive direct food assistance the United States had shipped to starving Europeans immediately after the war ended, the Marshall Plan at its core was focused on the intricate, sometimes obscure details of long-term economic restructuring, industrial and agricultural infrastructure, international finance and trade. The legislation setting up the European Recovery Program consisted of a relatively complex set of stipulations and interventions formulated by economists, technocrats and industrialists to rebuild European money markets and economic infrastructure.

In its simplest terms, then, the Marshall Plan was, as its official title implies, an economic recovery program rather than a humanitarian relief effort. It grew out of a consensus that developed within the Truman administration that, without help, struggling European economies with dwindling reserves of hard currency would be unable to participate in an international economy based on increased production, an efficient global distribution of products and an integrated global economy governed by liberal trade policies. That handicap, in turn, would render those governments vulnerable to communist takeovers.

Conceptually, the plan was rooted in a neoliberal world view advanced by powerful corporate interests that played a key role in Washington’s postwar planning. These proponents supported free markets, limited government intervention in the economy, and sustained economic growth. President Harry Truman, like Franklin Delano Roosevelt before him, drew the likes of W. Averell Harriman of the Union Pacific fortune, Edward Stettinius Jr. of U.S. Steel and James Forrestal of Dillon Reed into their innermost circles and appointed them to important government positions: Secretary of Commerce, Secretary of State and Secretary of Defense, respectively. Both FDR and Truman also sought input from a number of committees populated by influential members of the private sector, including the Committee for Economic Development, to develop economic plans for the postwar period.

It would be an oversimplification, however, to state that the Marshall Plan sprang only from the minds of these scions of industry and was primarily designed to benefit their narrow interests.

The CED, in particular, was intimately connected to the implementation of the Marshall Plan. Its chairman, Paul Hoffman, was the president of the Studebaker Automobile Company, and would go on to become the chief administrator of the agency that oversaw the program. The committee’s vice chairman, advertising executive William Benton, had been assistant secretary of State for public affairs from 1945 to 1947, while another key member, William Clayton, had served as under secretary of State for economic affairs from 1946 to 1947. Other CED members included top executives at General Foods, the Coca-Cola Company, Scott Paper, Quaker Oats, General Electric and Goldman Sachs, many of whom testified before Congress in support of assistance to Europe.

These leaders argued that unless Washington helped bolster European currency markets, to ensure that those nations would be able to purchase American-made goods on the global markets, the U.S. economy would suffer. This group of well-placed executives represented the interests of large consumer-goods corporations and favored large, capital-intensive units, global flows of capital and expanded international markets that would allow for easy accumulation of capital, increased consumer demand and more individual prosperity. This model, they argued, was crucial to sustaining the U.S. balance of trade, preserving American wealth and establishing a stable global market system.

It would be an oversimplification, however, to state that the Marshall Plan sprang only from the minds of these scions of industry and was primarily designed to benefit their narrow interests. Foreign Service officers within the Department of State also saw great promise in this approach to rebuilding Europe. In their view, the economic crisis in wartorn Europe represented an opportunity not just to assist key allies, but to remake the political and economic makeup of the region. The Marshall Plan’s efforts to integrate European markets and create a common trading area were the economic counterpart to the Department of State’s, and also the Pentagon’s, geopolitical policies focused on encouraging European political and military integration, policies that were ultimately embodied in such arrangements as the North Atlantic Treaty Organization.

Under the leadership of Foreign Service Officer George Kennan, who had recently returned from Embassy Moscow, the State Department Policy Planning staff participated in the detailed groundwork for European recovery planning. A variety of interagency committees staffed by junior Foreign Service officers sprang up around this effort and informed the work of the Policy Planning staff, and ultimately the department’s senior leadership—including William Clayton and George Marshall, who became Secretary of State in early 1947.

Kennan and other members of the Foreign Service’s rank and file agreed that Western European integration was the key to achieving an economically and strategically stronger continent. Specifically, this would require rebuilding the German economy while assuaging French concerns about a resurgent Germany. Both the Marshall Plan and military security arrangements like NATO required a balance of power within Europe, one that would reassure French concerns about a renewed Germany and also build a European political, strategic and economic infrastructure that would compel the United Kingdom to play a more direct role in European affairs. As a bonus, the plan was designed to lessen the appeal of communism and socialism in Western Europe.

Given general agreement within the executive branch and leadership circles that European recovery was essential to both U.S. economic and international security interests, Secretary of State George C. Marshall officially announced the Truman administration’s intent to pursue a major foreign assistance program in Europe during a brief commencement address at Harvard University on June 5, 1947. It would not be signed into law until nearly a year later.

Enacting the Marshall Plan

Rebuilding in Germany, circa 1948. The sign on the wall says “Berlin Emergency Program, with Marshall Plan help.”

U.S. National Archives and Records Administration / Wikimedia Commons

Despite its popularity in later years, the European Recovery Act generated genuine political opposition in the United States. Even within the executive branch, there was no consensus yet on how to administer European assistance, or even which agency should take the lead. So attaining congressional approval was no easy task.

While there was some general discomfort in Congress and other circles with the idea of the United States committing to sustained international involvement following a major war, the most vocal and specific opposition to the Marshall Plan came from a conservative coalition of Midwestern and Western members of the Republican Party, including Ohio Senator Robert Taft and former President Herbert Hoover, who were non-interventionist isolationists. But opposition also emerged in sectors of the U.S. economy whose interests did not align with the vision presented by Truman’s economic advisers.

For instance, owners of U.S.-based, labor-intensive manufacturing businesses and Midwestern agricultural interests, with strong Republican representation in Congress, initially favored protectionist tariffs over liberalized trade and argued that the United States should revert to a more isolationist economic stance after the war. Midterm elections in 1946 had delivered a Republican Congress in 1947 and caused some concern in the Truman administration that this setback would interfere with passing legislation for European recovery on the Hill.

However, Secretary of State George Marshall’s speech unveiling the plan had been well-timed. It came less than three months after President Truman had gone before Congress on March 12, 1947, to articulate what came to be known as the Truman Doctrine. In the course of asking Congress for support for the governments of Greece and Turkey against the threat of communist uprisings, Truman had announced that the United States was compelled to assist “free peoples” in their struggles against “totalitarian regimes,” because the spread of authoritarianism would “undermine the foundations of international peace and, hence, the security of the United States.”

In the words of the Truman Doctrine, it became “the policy of the United States to support free peoples who are resisting attempted subjugation by armed minorities or by outside pressures.” This stance would dominate U.S. foreign policy for decades to come and played a large role in providing a compelling argument for strong bipartisan support in Congress for U.S. assistance, both military and economic, to nations that might be susceptible to communist influence sponsored by the Soviet Union.

Congressional debate on the legislation that would fund the Marshall Plan began in the last weeks of 1947. By February 1948, polls suggested that 56 percent of the population surveyed viewed the proposal favorably. The business community, many farmers, internationalist “elites” and other groups favored it, recognizing the importance of European recovery for American prosperity. But isolationist Republicans, along with some conservative Southern Democrats, initially opposed the plan, arguing that vigorous overseas investment abroad would sideline key domestic priorities like the tax cut many Republicans wanted Truman to pass.

Despite its popularity in later years, the European Recovery Act generated genuine political opposition in the United States.

At Harvard, Marshall had promised that the U.S. commitment to reconstructing Europe would not only restore markets for American goods, but would ameliorate “poverty, desperation and chaos” and promote “economic health in the world, without which there can be no political stability.” This framing, as well as a number of other factors, served to mitigate the objections of the stronger voices of opposition. Sen. Taft and other legislators endorsed the use of aid to strengthen Europe against Soviet aggression but, being less susceptible to the argument that it would help sustain U.S. prosperity, argued that it should be limited in scope and not place an undue burden on American taxpayers.

The final authorization placed much of the onus of planning on the Europeans themselves, restricted the plan geographically, limited its scope and prescribed a delimited appropriation and duration for the disbursement of funds. This approach brought congressional Republicans on board as stakeholders in the plan.

The deep involvement of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, chaired by Senator Arthur Vandenberg (R-Mich.), was critical. Vandenberg permitted the committee hearings to be a forum for dissenting views, which enabled senators on both sides to hear from many experts. It also demonstrated the close partnership between Vandenberg and Marshall in forging the legislation.

Ultimately, congressional Republicans, including key isolationists like Taft, calculated that accepting a modified Marshall Plan, with a final allocation cut down from Truman’s request of $17 billion to $13 billion, and implementation mechanisms external to the State Department, like the Economic Cooperation Administration and the Organization for European Economic Cooperation, was better than opposing the ERP outright.

Thanks to bipartisanship and the Truman administration’s willingness to make some concessions, the legislation passed overwhelmingly in both houses. The Marshall Plan represented not only a moment of consensus within the executive branch on foreign policy, but also a domestic U.S. political success.

Implementing the Marshall Plan

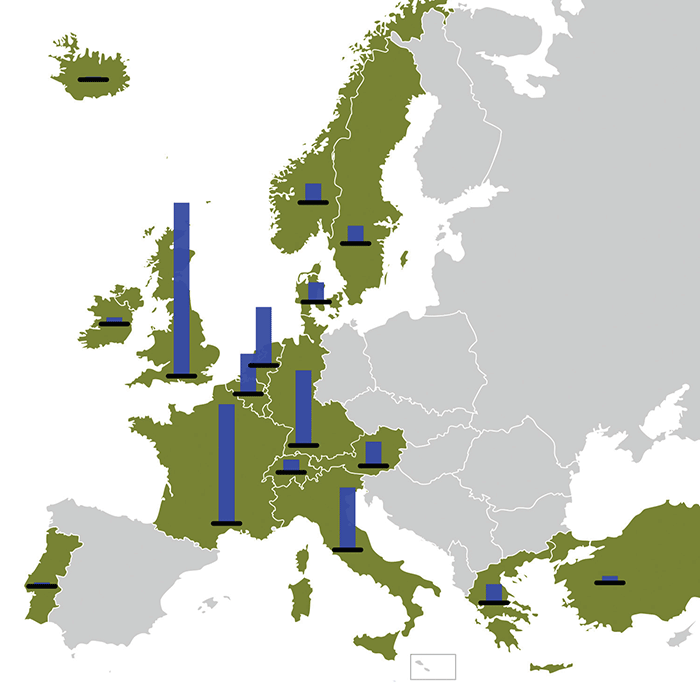

Map of Cold War–era Europe showing countries that received Marshall Plan aid. The blue columns show the relative amount of total aid per nation.

U.S. National Archives and Records Administration / Wikimedia Commons

Given that the Marshall Plan was an important diplomatic venture, the State Department had originally assumed that it would take the lead in the administration of the recovery program, both in Washington and overseas. High-ranking officials, including Under Secretary of State Robert Lovett (who held the second-ranking position at State at the time), recommended establishing a new bureau within the department, led by a new assistant secretary, to oversee Marshall Plan operations and other foreign assistance programs.

Initial State Department recommendations also envisioned U.S. embassy staff administering the program, with Marshall Plan personnel falling under the direct purview of the Foreign Service. However, interagency competition and the threat that congressional pushback might result in restrictions on funding led to the decision to locate the European Recovery Program bureaucracy within the independent European Cooperation Administration, rather than within the State Department or the Foreign Service.

Thus the ECA’s administrator, Paul Hoffman, oversaw all operational aspects of the Marshall Plan with the assistance of the Office of the Special Representative, which was based in Paris to orchestrate the various ECA missions in the 16 aid-recipient countries. Former Secretary of Commerce W. Averell Harriman served as the first Special Representative and oversaw the work of more than 600 Americans and 800 locally employed staff in Europe. Although it did not directly oversee implementation of the Marshall Plan, the State Department played an important role continuing the usual business of maintaining bilateral relations with host nations and negotiating the bilateral agreements necessary to set up each of the ECA country missions.

The ERP also required that the European aid recipients play an active role in their own recovery. The 16 Marshall Plan nations established the Organization for European Economic Recovery as a regional organization to help coordinate the assistance program, and also to present a coherent assessment of their individual and regional needs. Each recipient country established its own national unit, responsible for liaising with the OEEC in Paris and with the relevant ECA office country director. Their job was to advise the two entities of their specific needs in various sectors so that the OEEC could make allocation recommendations to Washington.

The final authorization placed much of the onus of planning on the Europeans themselves, restricted the plan geographically, limited its scope and prescribed a delimited appropriation and duration for the disbursement of funds.

As with the initial assessment of assistance needs, the recipient nations each played a large role in requesting and processing the disbursement of Marshall Plan aid—a setup Congress specified in the empowering legislation to save administrative costs. While the various ECA country units evaluated each request against the OEEC allotments, local European entities processed the approved procurements and met local banking and transportation needs.

Although the ECA paid U.S. suppliers of commodities in dollars, the program required aid recipients to pay for any goods received in local currency and deposit them in national counterpart funds. A small portion of these funds paid for ECA administrative costs, while the remainder became available to recipient governments for rebuilding their industrial, agricultural and financial infrastructure.

Evaluating the Marshall Plan

All told, the U.S. provided $13.3 billion (about $140 billion in 2017 dollars) in assistance between 1948 and 1951 to 16 Western European countries through the ECA, with the vast majority of funds allotted to commodity purchases. Historians have generally agreed that the Marshall Plan contributed to reviving the Western European economies by controlling inflation, reviving trade and restoring production. It also helped rebuild infrastructure through the local currency counterpart funds.

What is notable about this assistance is that the Europeans themselves played a major role in the planning and implementation of the ERP. U.S. assistance may have provided the margin the recipient countries needed to help themselves get on a path to stable postwar recovery, but the fact that Europeans generally agreed with the basic stipulations of the assistance package—that some form of capitalism should inform postwar economics and governance—ultimately made the Marshall Plan a success.

Congress did not renew Marshall Plan funding beyond its originally legislated end date of 1952. With strides already made, it was harder for supporters to argue for additional assistance funds under the ERP. Moreover, following the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950, American interest in international assistance turned away from a focus on economic development toward defense funding, and supporting military strength and rearmament in Europe as a bulwark against the Soviet Union and international communism.

Even so, there is no denying that the Marshall Plan played a major role in setting Western Europe on a long-term path to recovery and political and economic stability.