Enhancing Resilience

The ability to adapt in the presence of risk and adversity is crucial for members of the Foreign Service. Happily, it’s a talent that can be learned.

BY BETH PAYNE

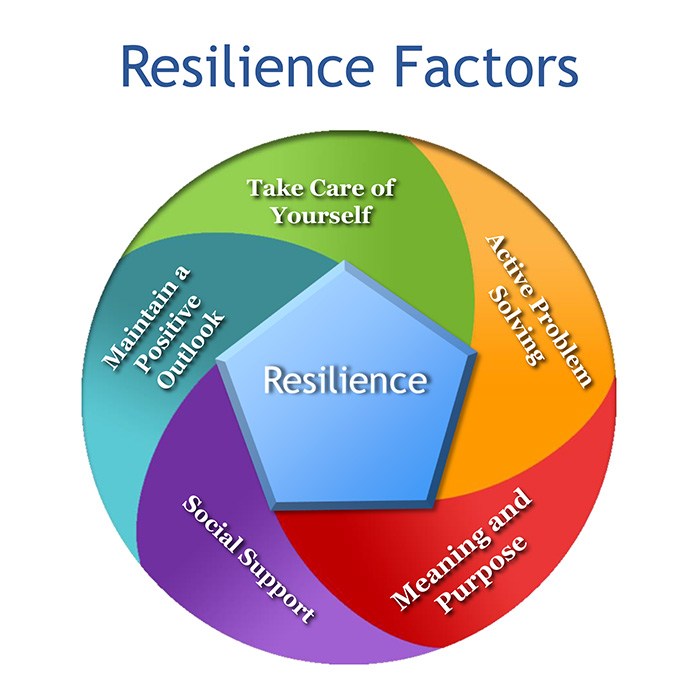

There are five basic factors that contribute to personal resilience.

U.S. State Department / FSI / CEFAR

Research shows that resilience—the capacity to adapt successfully in the presence of risk and adversity and to bounce back from setbacks, trauma and high stress—is an important attribute often found in highly successful individuals. This has obvious implications for Foreign Service professionals since resilient people and teams are able to innovate and thrive despite stressful, rapidly changing or high threat environments.

People with low resilience often display common characteristics, including irritability, anger, persistent illness, trouble sleeping, moodiness, poor memory, reckless behavior and lack of hope. Teams with low resilience may have low productivity, office conflict and lots of sick leave; they may lack innovation, problem solving and future planning. These behaviors often interfere with our ability to achieve foreign policy goals, particularly when an embassy or consulate is hit by an unanticipated crisis.

Fortunately, resilience is not just an innate trait you are either born with or not. Rather, it is a state of being that people and organizations can develop by engaging in resilience building behaviors and activities. Resilient leaders have high energy and motivate staff; when they foster resilience in their workplaces, their teams are more innovative, collaborative and productive.

As director of the Office of Children’s Issues from 2011 to 2014, I saw this firsthand. We became more proactive and effective as the resilience of the team improved. With high resilience, we were better able to work with colleagues in other agencies and across the State Department to achieve ambitious goals, such as passing adoption fraud legislation and persuading intransigent countries to join the Hague Convention on child abduction.

I now run the Foreign Service Institute’s Center of Excellence in Foreign Affairs Resilience (FSI/TC/CEFAR), where we developed a personal resilience model that draws from leading resilience research in the fields of organizational development, psychiatry, neuroscience, social/cognitive science and disaster relief. We’ve identified five leading indicators of a person’s resilience. Intentionally enhancing these aspects of one’s life will increase personal resilience and, in turn, bolster the capacity to handle challenges.

Five Leading Indicators of Resilience

Self Care. Daily physical activity, healthy eating, sufficient sleep and taking time to recover are essential for both shortterm and long-term resilience. We often overlook the need to recover—which can be as simple as taking a walk in a park, meditating or working on a jigsaw puzzle. This can be a challenge in the Foreign Service, which is definitely not a 40-houra- week job. If you face long workdays and overwhelming workloads, build in short breaks and vacation days that allow time to recover from periods of high-intensity work.

Study your daily and weekly routines and schedule the time you need to focus on each of the following four components. Prepare someone to act for you when you’re on vacation, and then resist the temptation to stay engaged when you should be disconnecting.

Active Problem-Solving. Your level of resilience directly correlates to your ability to maintain a sense of control, even over the smallest things. Spend time and mental energy on issues you can control and influence, while letting go of things that are outside of your control. If you can’t influence larger foreign policy goals, find aspects of foreign policy you can influence, and focus on those smaller pieces so you have a sense of control.

Establish goals for yourself, and work toward these goals with intention. Every time I bid, I start by setting goals for my next post, both personal and professional, and then bid on those countries that best meet my goals rather than getting distracted by myriad pros and cons that come with each potential bid.

Set clear boundaries; communicate them to colleagues, friends and family, and then use your boundaries to turn down requests and work that would otherwise overwhelm you. You can say no diplomatically, explaining why your refusal will best achieve the foreign policy goals you are focused on. Remember that it is better to disappoint someone early by saying no than later by being so overwhelmed you either submit substandard work or don’t keep your promise.

Ask “why” multiple times to get to the root of a problem. We often try to solve the wrong problem because we fail to see the root causes. We expend a lot of energy and then wonder why we haven’t achieved results. Take the time to find out the real problem before developing your strategy.

Spend time and mental energy on issues you can control and influence, while letting go of things that are outside of your control.

Ask for help when you need it. In the Foreign Service, there is a strong culture of going it alone, which is unfortunate. All of us need support from time to time—reaching out for help is a sign of strength.

Positive Outlook. Maintaining a positive outlook is essential to personal resilience. Consciously focus on what is going well in your life, and positively reframe the parts that aren’t going so well. Positive reframing might require you to zoom your perspective in or out, or look at an issue from a different angle. I’ll never forget how upset I was when I didn’t get my dream job, but then I broadened my perspective and ended up with a great opportunity at FSI, which led to my current job.

Spend time every day thinking about what you are grateful for, and then express that gratefulness to colleagues, friends and family. Write a thank-you note to someone to whom you are grateful at the end of each day. Spending a few minutes thinking about the good things that happen each day is healthier than focusing on the negatives.

Laugh often. If you’ve had a particularly stressful day, watch a funny YouTube video or sitcom. Keep yourself humble by engaging in self-deprecating humor.

Meaning and Purpose. Research indicates that a person’s sense of meaning and purpose directly links to their personal resilience. Find ways to routinely insert meaning and purpose into your life. While many of us in the Foreign Service find significant meaning in our work, we often overlook other areas such as religion, family, service projects, volunteer work or hobbies. When we have a crisis of meaning at work, we have no other purpose to fall back on. Make time for activities that give purpose to your life outside of work. Be passionate about something. Be helpful to others.

The Center of Excellence in Foreign Affairs Resilience was established in 2016.

Social Support. In-person social interactions and meaningful relationships are essential to your well-being and personal resilience. The depth of individual relationships outweighs the number of connections one has. Life in the Foreign Service can take its toll on social support networks, which means you have to be more intentional about building and maintaining relationships.

Nurture your friendships and family relationships by making time for visits and phone calls. Spend some of your R&R and vacation visiting friends and family, and encourage them to visit you at post.

Build support among your work colleagues. One of my best friends is someone I never would have gotten to know in Washington, D.C. But when we found ourselves at a small post with few single women, we overlooked our differences and built a lasting bond.

For my fellow introverts: Resist the temptation when feeling down to isolate yourself, and instead spend time with a close friend who won’t drain you of energy.

Building and maintaining resilience will not only prepare you for the unexpected. It will also help you adapt to change, succeed despite uncertainty and achieve difficult foreign policy goals. You’ll become a better Foreign Service professional, friend and family member, as well.

For more information about how to build resilience, individuals with State Department Open Net access can subscribe to CEFAR’s blog at: http://cas.state.gov/fosteringresilience or contact CEFAR at FSITCresilience@state.gov.