FS Institution Builder and Africa Hand

A CONVERSATION WITH AMBASSADOR HANK COHEN

2019 RECIPIENT OF THE AWARD FOR LIFETIME CONTRIBUTIONS TO AMERICAN DIPLOMACY

Career Ambassador Herman Jay Cohen (universally known simply as Hank) received the American Foreign Service Association’s 2019 Lifetime Contributions to American Diplomacy Award at an Oct. 16 ceremony in the Dean Acheson Auditorium at the Department of State. (For coverage of the ceremony, see AFSA News, p. 62.)

AFSA / Joaquin Sosá

He is the 25th recipient of the award, given annually in recognition of a distinguished practitioner’s career and enduring devotion to diplomacy. Past recipients of this award include George H.W. Bush, Thomas Pickering, Ruth Davis, George Shultz, Richard Lugar, Joan Clark, Ronald Neumann, Sam Nunn, Rozanne Ridgway, Nancy Powell and William Harrop.

Hank Cohen was born in New York City, New York, on Feb. 10, 1932. He earned a B.A. in political science from the City College of New York in 1952, and an M.A. in international relations from American University in 1962. Mr. Cohen served in the United States Army as a second lieutenant infantry platoon leader in Germany from 1953 to 1955, receiving an officer’s commission via the Reserve Officer’s Training Corps.

Mr. Cohen joined the Foreign Service in 1955 and served as a consular officer in Paris for three years. In 1958 he returned to Washington, D.C., as the first Foreign Service officer to work in the Bureau of Educational and Cultural Exchange. He remained there until 1961.

Next came six months of labor training, followed by four consecutive assignments as a labor attaché (often with ancillary duties as a consular, economic or political officer) in Africa: Kampala, Uganda (1962-1963); Salisbury, Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe, 1963-1965); Lusaka, Zambia (1965-1966); and Kinshasa, Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo, 1966-1969).

From 1969 to 1974, Mr. Cohen directed the State Department’s Office of Central African Affairs. After three years as political counselor in Paris (1974-1977), he was named ambassador to Senegal and The Gambia, based in Dakar, where he served from 1977 to 1980.

Ambassador Cohen then returned to Washington to serve as principal deputy assistant secretary of State for intelligence and research (1980-1984) and principal deputy assistant secretary for personnel (1984-1987). In 1987, Amb. Cohen was appointed as special assistant to the president and senior director for Africa at the National Security Council, a position he held for two years.

That is the beauty of the Foreign Service. One can be both part of the workforce and part of management.

From 1989 to 1993, he served as assistant secretary of State for African affairs and was promoted to the rank of Career Ambassador in 1992.

After retiring from the Foreign Service in 1993, Amb. Cohen served as a senior adviser to the Global Coalition for Africa, an intergovernmental body assisting African governments to adopt sound economic policies, through 1998. He then became a professorial lecturer in Africa studies at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies, a position he held until 2010.

Hank Cohen, State Department, 1977.

Since 1994, he has been president and chief executive officer of Cohen and Woods International, an international consulting firm specializing in providing services to American companies interested in doing business in Africa. Amb. Cohen was also a member of the board of directors of Hyperdynamics Oil and Gas from 2009 to 2016.

He is the author of two books: Intervening in Africa: Superpower Peacemaking in a Troubled Continent (Macmillan, 2000) and The Mind of the African Strong Man: Conversations with Dictators, Statesmen and Father Figures (New Academia, 2015). He is also co-author of an audiobook, Who Lost Congo? The Consequences of Covert Action (Foreign Affairs, 2015).

In addition to Hank Cohen’s Africa Blog (http://www.cohenonafrica.com/publications), he has a Twitter account—@cohenonafrica—where he tweets in English and French. It currently has more than 21,000 followers.

AFSA conferred its Christian A. Herter Award for Constructive Dissent by a Senior Officer on Amb. Cohen in 1982. And in 1999, it presented him with a Special Achievement Award in recognition of his many contributions to the organization over the previous three decades—from his role as one of the “Young Turks” who helped AFSA modernize and unionize in the early 1970s to his multiple terms as a member of the association’s Governing Board.

Before AFSA had a large Labor Management Office, Mr. Cohen chaired the Members’ Interests Committee for many years, negotiating with the State Department for benefits and allowances to improve the quality of life for personnel serving overseas. Later he chaired AFSA’s Insurance Committee during the period when the union sponsored a variety of insurance policies for members, and chaired other committees that obtained many of the benefits and allowances that Foreign Service personnel and their families now take for granted.

For instance, Mr. Cohen led AFSA’s successful effort to obtain the first educational allowances for kindergartners; he was instrumental in getting housing and shipment allowances for Foreign Service specialists raised to match those of FSOs and in resolving long battles with State about overtime pay for secretaries, communicators and other staff in their favor. He also wrote the first state tax guide for The Foreign Service Journal, an annual feature that is always very popular with members.

When I saw that 35 African colonies were about to become independent just as I was beginning my career, I saw an opportunity to apply economic theory to the real developing world.

Amb. Cohen has received the Distinguished Foreign Service Presidential Award, the Foreign Service Director General’s Cup, the Douglas Dillon Award for Best Writing on Diplomatic Practice, the French Legion of Honor and the Belgian Order of Leopold II. He is currently a member of the Council on Foreign Relations, the American Academy of Diplomacy and AFSA.

Mr. Cohen is married to the former Suzanne Karpman, who worked for the Voice of America as a French-language correspondent and for the Foreign Service Institute and the Central Intelligence Agency as a French-language instructor. The couple have two sons, Marc and Alain, who are technology entrepreneurs.

FSJ Editor Shawn Dorman conducted the following interview with Amb. Cohen via email in October.

Hank Cohen (at right) and Secretary of State James Baker meet with President Kenneth Kaunda of Zambia in 1990.

Courtesy of Herman J. Cohen

FSJ: Congratulations on receiving AFSA’s lifetime contributions to diplomacy award, which is well deserved. You’ve had a fascinating career, both inside and outside government. I understand you decided to apply to the Foreign Service in 1953, while you were still an undergraduate at City College. What was the impetus for that decision?

HJC: My favorite subjects were “Theory of International Relations” and “Comparative European Governments.” My professor for both courses was Bernard E. Brown. He encouraged me to take the Foreign Service examination, arguing that hardly any City College graduates were in the Foreign Service. In any event, I wanted to have a career in the international sphere, possibly in business or journalism. When I was informed that I had been successful in the examination, I decided to pursue a career in the State Department.

FSJ: What were your impressions of the Foreign Service application process? Did it involve both a written exam and oral assessment at that time?

HJC: It was quite a comprehensive and very long exam in those days. It lasted three days, with lots of essay writing. There was also an oral assessment. Unlike today, the retired FSOs who administered the oral examination did not have a script. They asked whatever questions they considered suitable for each individual. For example, they asked me major league baseball questions, including who played third base for the Pittsburgh Pirates. They also asked me to describe the differences between the British Labor Party and the British Conservative Party. I expressed the view that there was virtually no difference. This set off a rather heated discussion among the examiners. In general, they appeared to appreciate my “American-ness.”

FSJ: What were your impressions of orientation and entry-level training?

HJC: I considered the A-100 course to be quite comprehensive with respect to the varied functions of the Foreign Service. There was also a lot of practical advice on the side from the senior officers with lots of experience, during coffee breaks. The detail on consular work was particularly useful.

Overseas Assignments

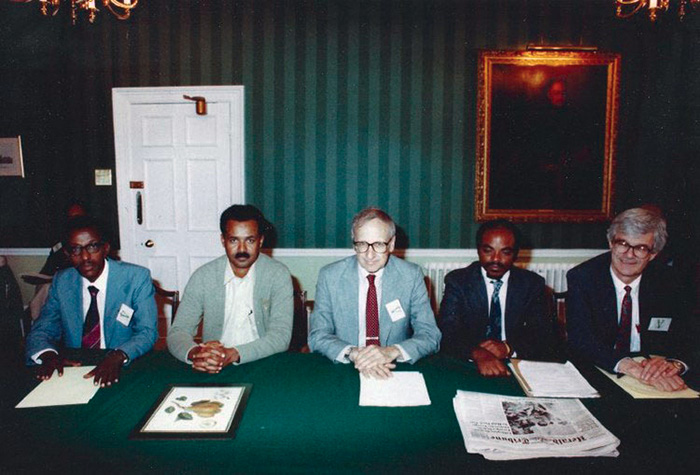

Ending the war for Eritrean independence: London, England, May 31, 1991. Hank Cohen is at the center. To his left is Prime Minister Meles Zenawi of Ethiopia. To his right is President Isayas Afwerki of Eritrea.

Courtesy of Herman J. Cohen

FSJ: Your colleagues must have been jealous when you got assigned to Paris as your first Foreign Service posting. Was that because you were fluent in French?

HJC: On the contrary. After several weeks of French training, I flunked the language examination. For that reason, I was sent to Paris to improve. Most of my colleagues went to Palermo and Naples to do refugee relief processing. Their jealousy was palpable.

FSJ: Did your three years as a consular officer in Paris give you a good introduction to the Service?

HJC: I served in the Paris visa section. Every embassy section had an interest in visas because so many of their key contacts were traveling to the United States. With so many people having been members of the Communist Party, we were constantly working to get visa waivers for important travelers. Because of my embassy contacts, I decided to take training to be a labor attaché.

FSJ: How different was France when you returned 16 years later to serve as political counselor?

HJC: The progress of economic development was remarkable. Where there was very little automobile traffic in 1955, traffic jams were abundant in 1974. There were many new buildings in Paris, especially apartment houses. Tourism was massive.

FSJ: Tell us a bit about your assignment as chief of mission to Senegal and The Gambia.

HJC: Senegal and The Gambia have Muslim-majority populations. The people are very tolerant and welcoming. At Christmastime they celebrate with lights and gift giving. The educated people are quite sophisticated and a pleasure to talk to.

FSJ: You spent nearly all of the 1960s as a labor attaché. What led you to focus on labor issues?

HJC: I come from a blue-collar family associated with labor unions. I grew up in a working-class neighborhood in New York. In my first assignment in Paris, working with the embassy labor attaché on visa issues, I saw how important labor movements are with respect to both politics and economics. Labor unions are a separate and unique window into the political system.

FSJ: You are, of course, best known as an Africa hand. What made you decide to concentrate on that part of the world?

HJC: While majoring in international affairs in college, I did a thesis comparing economic planning in India and Brazil. That gave me a new interest in the economics of the developing world. And when I saw that 35 African colonies were about to become independent just as I was beginning my career, I saw an opportunity to apply economic theory to the real developing world.

FSJ: What were some of the opportunities and challenges you’ve experienced working in that region, both as an FSO and now?

HJC: The fact that the new African political leadership was so open to ideas constituted a great opportunity for an American diplomat because the United States had a strong reputation as a proponent of ending colonialism. The American voice was trusted. As an American diplomat, I felt proud that I was constantly being called on for advice.

FSJ: Do you feel Africa is coming into its own on the world stage? Should the United States be doing more to promote political and economic reform there? If so, how?

HJC: Africa has not moved ahead rapidly, neither in economic development nor political democracy. Africa is far less successful than Southeast Asia and Latin America. I attribute this mainly to poor governance. I am pleased that U.S. policy started to emphasize good governance in Africa when I was assistant secretary. Progress has been much too slow, however.

FSJ: You were able to get to know every first-generation African leader (Mandela, Mobutu, Gaddafi and many others). I know you wrote a whole book about this, but could you tell us something of what you learned through those relationships?

HJC: Most of the African leaders whom I got to know well did not wake up in the morning and ask themselves, “What am I going to do for my people today?” Most of them were more interested in enhancing their personal power. Mandela was a notable exception, as were several other leaders in southern Africa. I attribute this to the presence of Christianity in Southern Africa for more than 400 years. In the rest of Africa, Judeo- Christian values have yet to become strong. Washington Assignments

Curiosity is probably the most important element of successful diplomacy. I spent most of my career abroad asking questions.

FSJ: When you came back to Washington from Kinshasa in 1969, it was to head the Office of Central African Affairs, right? What were some of the main issues you handled during five years with the African Affairs Bureau?

HJC: We had to cope with some crises. For example, there was a major genocide in the Republic of Burundi in 1972. Minority Tutsis, who were in power, became frightened by educated persons in the majority Hutu community who were demanding political equality. They started to murder educated Hutus, as vividly reported by Embassy Bujumbura at the time. What astonished me was that there was so little interest in this unfolding tragedy. The press, the U.S. Congress, the nongovernmental organizations were indifferent. I was going crazy trying to galvanize higher levels.

Finally, I persuaded the president of neighboring Tanzania to cut off Burundi’s railway to the port of Dar es Salaam. That ended the genocide. But there was a follow-up. Congressional hearings, at which I was the chief witness, resulted in legislation in 1976 requiring the State Department to produce an annual human rights report on every country receiving U.S. development assistance. That annual report still exists, and is as important as ever.

FSJ: You helped guide U.S. policy toward Africa, both at the National Security Council and then as head of AF. Could you compare those experiences?

HJC: In the NSC, I was special assistant to President Ronald Reagan for Africa. I had to be careful not to let it go to my head. There was the State Department assistant secretary for Africa and counterparts from every agency. I decided to coordinate policy, rather than make policy. That worked out very well, with a major achievement in the December 1988 accords resulting in the independence of Namibia, the departure of both Cuban and South African troops from Angola. I found President Reagan to be very smart about foreign policy, and quite willing to listen to advice.

FSJ: What would you identify as your main challenges and achievements during your four years as head of the Bureau of African Affairs?

HJC: There were four major civil wars going on in four important African countries when I arrived to head up the Africa bureau in April 1989. We decided that nothing good could happen while those wars were going on. We decided to make conflict resolution our highest priority. Mediation by the AF Bureau brought peace to Ethiopia/Eritrea, Angola and Mozambique. We were very proud of our achievement.

FSJ: How was your time as principal deputy assistant secretary for the Bureau of Intelligence and Research in the early 1980s? (Ron Spiers was INR’s head, right? What was it like to work for him?)

HJC: I started as principal deputy assistant secretary under Ron Spiers, a great professional and extremely insightful about U.S. foreign policy and what was doable and not doable. Ron left shortly to be U.S. ambassador to Turkey, and his successor was Hugh Montgomery, a senior CIA officer. As directed by Secretary of State Al Haig, he spent most of his time trying to prove that the Soviets tried to assassinate the Pope. That left me in charge. When President Reagan decided to send troops to Lebanon in 1982 as a goodwill gesture, I sent the INR analysis that the U.S. troops would be seen as enemies and not friends. I kept repeating it until Secretary of State George Shultz told us to shut up. The endgame was tragic. For my warnings, I received AFSA’s Christian A. Herter Award for Constructive Dissent by a member of the Senior Foreign Service in 1982. I wish it had been different.

In March 1990, Nelson Mandela, recently released after 27 years in prison, enters the State Department with Hank Cohen at the beginning of his first official visit to the United States.

Courtesy of Herman J. Cohen

The Role of AFSA

FSJ: You’ve been a large figure in AFSA’s history. When did you join the association?

HJC: I joined AFSA in 1955 when I entered the Service.

FSJ: How did you get involved with Lannon Walker and the “Young Turks” who were trying to reform and strengthen AFSA?

HJC: When I became active in 1971-1974, the “Young Turk” leadership consisted of Bill Harrop, Tex Harris and Tom Boyatt. Lannon came later. I had known Bill Harrop when we were both assigned to the Congo. He asked me to take over members’ interests in 1972. I accepted the challenge with enthusiasm.

FSJ: Given your many years negotiating with State on behalf of AFSA members, was it awkward to sit across the table from AFSA’s leaders during your years as Deputy Director General of the Foreign Service? If so, how did you handle that?

HJC: That is the beauty of the Foreign Service. One can be both part of the workforce and part of management. When I was Deputy Director General, there were not many difficult issues on the table. I believe the issue of promotion precepts was somewhat difficult, but not overwhelming. Where I innovated was to have a strong grievance officer who was under my orders to find solutions at the first level, and not permit grievances to rise to higher levels. We had very few grievances go to appeals boards.

FSJ: In your view, is AFSA still strong today? Has its role changed? Should it?

HJC: AFSA became a professional organization about 100 years ago. It became a collective bargaining agent nearly 50 years ago. I believe that AFSA’s role as a collective bargaining agent has made it stronger as a professional association.

FSJ: What should AFSA’s primary focus be today?

HJC: AFSA needs to concentrate on upholding professional standards and, above all, to protecting the professionals in the Service from being dragged into domestic politics that are leaking into foreign relations. I believe that AFSA is currently involved in real-time issues of this nature and is courageously fighting back.

Life after the FS

FSJ: Instead of taking a well-deserved break when you retired from the Foreign Service in 1993, you became a senior adviser to the Global Coalition for Africa almost right away. What did that position entail?

HJC: The GCA was an intergovernmental body bringing together African finance ministers and donor nations. Our mission was to discuss, at a high level, how to make African economies stronger and speed up their growth. It was chaired by Robert McNamara, who was a pleasure to work with. He was full of wisdom. My life did not change much from State because I was meeting with the same senior African leaders I had known as assistant secretary. From them I learned how difficult it is to overcome cultural impediments to progress. Corruption was extremely strong in most countries, and hard for even determined politicians to stop.

FSJ: Your long interest in Africa is obviously as strong as ever. What are some of the main issues you track there today? Are there any trends you can point to that we should watch?

HJC: A major phenomenon is a massive youth bulge. Thirty percent of Africans are under 30. Major reforms are needed to create jobs for them, and agriculture must be modernized to feed them. I see some leadership understanding this, for example, in Ghana, South Africa, Côte d’Ivoire and Kenya. They have enlightened leadership. Unfortunately, in the biggest African countries—Congo, Nigeria and Sudan—corruption continues to prevail. This is a prelude to real trouble in those countries.

Ambassador Hank Cohen at Washington, D.C.’sWorld Affairs Council in 2015.

Courtesy of Herman J. Cohen

FSJ: For 25 years, you have led Cohen and Woods International, an international consulting firm that advises and assists U.S. companies doing business in Africa. What can you tell us about that work?

HJC: We advise American companies that want to do business in Africa. A good example is the ContourGlobal company of New York, which invests in power generation. The investment is totally private. The host government signs a contract to purchase power for 20 years. The host government invests nothing. It is a great way to overcome Africa’s power deficit. I have negotiated six such investments for ContourGlobal: three in Nigeria, one in Rwanda, one in Togo and one in Senegal.

We are also working with a U.S. company, GFS Solutions, to do affordable housing. They produce houses that sell for $40,000 to civil servants and Army officers, who take out mortgages. We help with government negotiations and the search for finance.

When a friendly African government asks us to lobby for them in Washington, we usually accept. Our emphasis is not so much on defending their interests with the U.S. government, but on advising them on what the policy challenges are and how to define their own approach.

FSJ: You say on your blog that when you have found “that clients who I hoped would follow my guidance did not move in that direction, I ended my relationships with them.” Is that what happened with Robert Mugabe?

HJC: Yes, I advised Robert Mugabe to accept an International Monetary Fund stabilization program. Instead he started to seize white-owned farms, resulting in a total decline of the economy within a few years. With that action, I decided there was no reason for me to continue trying to help him.

FSJ: Many believed the situation in Zimbabwe would improve with Robert Mugabe out of office, but that does not seem to have happened. What can the United States do, if anything, to help in that crisis?

HJC: The Zimbabwean army took control of the main sources of state revenue about 10 years ago. Mugabe’s overthrow in a coup was engineered by the minister of defense who is backed by the army. Post-Mugabe has really been the same as Mugabe, with the army monopolizing state revenue.

FSJ: I understand you have a new book coming out shortly. Can you tell us about it? What is the central theme of the book?

HJC: The book is titled U.S. Policy Toward Africa: Eight Decades of Realpolitik. In it I describe U.S. policy toward Africa beginning in 1942 and going all the way to Trump. I reached several conclusions as a result of the research: (1) The Cold War never had any influence on U.S. policy toward Africa. Economic development was consistently our priority in Africa in every administration. (2) With respect to economic development, we were constantly experimenting because most of the programs were not working. Growth has been very slow. (3) The key reform that the Africans need to adopt is to create an enabling environment for private investment. After all these years, the rule of law and other requirements for investments continue to be absent in most of the countries.

Diplomacy and the Foreign Service Today

FSJ: Is the United States being “outplayed” in Africa by China? By Russia? How can the United States best compete for influence and business in Africa?

HJC: The United States is not being “outplayed” in Africa by China and Russia. China is doing a lot of infrastructure work in Africa financed by soft loans. The amount of debt toward China is now so large, there is no way the Africans can pay it back. In addition, the work done by Chinese state-owned companies is often shoddy. Roads wear out in two years. As for Russia, they have nothing to offer beside arms and mercenaries. They like, of course, to take control of gold mines to pay for their services. U.S., European and Japanese investors are all doing far more good work in Africa than China and Russia. The big problem remains the absence of security for investors. Despite this, the United States is in Africa in a big way and is highly respected.

FSJ: What are the essential ingredients for a successful diplomat?

HJC: The successful diplomat should be interested mainly in absorbing the culture of other nations in order to better understand why they make certain decisions and say what they do. Curiosity is probably the most important element of successful diplomacy. I spent most of my career abroad asking questions.

FSJ: Is the Foreign Service as an institution strong today? How has the role of the Foreign Service changed?

HJC: The Foreign Service is more important and more essential than ever. The world is very diverse and very complicated. CNN and Al-Jazeera cannot tell the policymaker what is really going on abroad. The Foreign Service, on the ground abroad, is the main instrument for Washington to be able to decide on policies toward countries and regions. Also, with so many U.S. government agencies having personnel abroad in U.S. embassies, the Foreign Service is needed to coordinate so that everyone is on the same page.

[Members of the Foreign Service] need to continue speaking the truth to power, and make sure that policymakers understand the negative foreign policy consequences of politicizing professional diplomacy.

FSJ: What areas, either functional or regional, would you point to that may require increased focus for American diplomacy in the coming years?

HJC: The Middle East will continue to be unstable for years to come, and will require close U.S. attention. Action must be taken to stabilize Libya, which is a major source of Islamic terrorism in the African Sahel countries. In the long run, the major issue facing U.S. foreign policy will be climate change. I believe that all new U.S. Foreign Service classes should provide extensive knowledge about climate change. Should the United States be playing a leadership role in climate change diplomacy? Yes.

FSJ: Are you optimistic about the future of professional diplomacy?

HJC: Yes. Professional diplomacy is more indispensable than ever. U.S. foreign policy cannot be made rationally without the in-depth knowledge of foreign cultures that only the Foreign Service can provide.

FSJ: There’s no denying the last few years have been hard on diplomats and diplomacy, and many senior diplomats have left the Service. What’s your advice to those wondering whether to stay or leave?

HJC: Foreign Service life is very difficult. Moving families around the world is not a picnic. Add to that efforts by administrations to politicize the career Service, and the stress level is high. Some senior diplomats cannot accept working under those conditions. I hope that most will remain because their expertise and wisdom are needed even more during periods such as the one we are currently experiencing.

FSJ: How should active-duty FS members protect the Foreign Service and State Department, and each other, as they find themselves in the crosshairs of an impeachment inquiry related to U.S. relations with Ukraine?

HJC: They need to continue speaking the truth to power, and make sure that policymakers understand the negative foreign policy consequences of politicizing professional diplomacy.

FSJ: What would be your advice to college students and recent graduates seeking to enter the Foreign Service or government service more generally?

HJC: There can be no more rewarding experience than professional government service that is protecting U.S. interests around the world. The U.S. Foreign Service is truly on the front line of U.S. national security.