The Swedish Cannonball

Reflections

BY JONATHAN B. RICKERT

Jonathan Rickert

In June 1995, while I was still serving in Bucharest before taking over as director in the State Department’s Office of North Central European Affairs, I made a brief familiarization visit to Warsaw. Though Poland was by far the most populous and, in some ways, most important country in what was to be my new portfolio, I had never been there before.

Among those whom I encountered at the embassy during my orientation meetings was my old friend, U.S. Defense Attaché Col. Branko Marinovich. It was a pleasure to see the Montenegro-born Branko again—he had been our next-door neighbor in Bucharest for about two years and was an enthusiastic antiquer. He kindly offered to show me around town a bit after I had finished my program for the day.

While perambulating, Branko took me to an antique store in the completely and beautifully rebuilt old town area of Warsaw. He wanted to show me something special there, he said, with a twinkle in his eye. On the floor of the store was a large carton filled with baseball-sized, old-looking iron spheres: cannonballs.

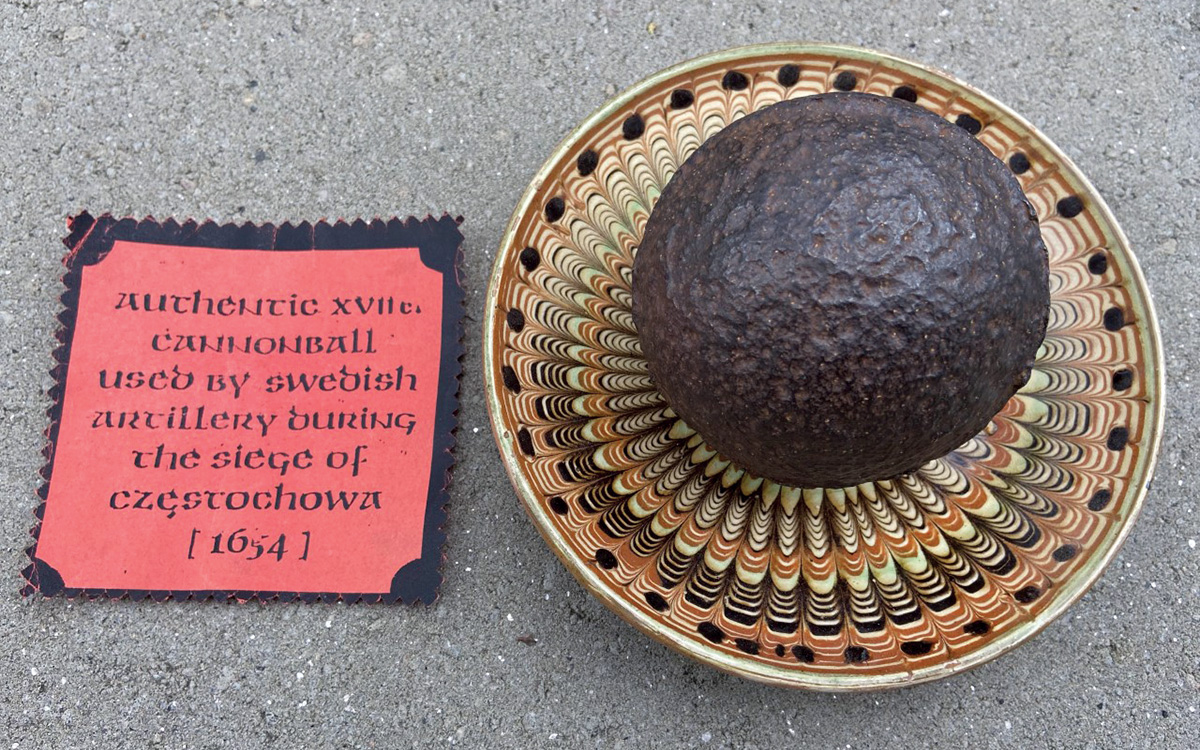

Branko pointed to the English-language, photocopied “certificate of authenticity” accompanying each projectile. It read: “Authentic XVII c. cannonball used by Swedish artillery during the siege of Czestochowa [1654, sic].” The price of each was the equivalent of about $5. Knowing of my Swedish connections (my wife, Gerd, hails from there), Branko urged me to buy one.

As I learned subsequently through some online research, the Swedish siege of Czestochowa (more accurately, the siege of the Jasna Gora Monastery), which took place in late 1655 during the Second Northern War or Deluge (1655-1660), was an important event in Polish history. It pitted the Protestant Swedes and their allies against the Roman Catholic Poles and theirs. The fortified monastery and home to the famous Black Madonna icon was stoutly defended by a small band of monks and volunteers.

This band successfully held off a much more numerous Swedish-led force, largely comprising German and other mercenaries. Both sides used cannons, mainly four- and six-pounders on the Swedish side (the cannonball I obtained weighs just over four pounds). The Protestant forces withdrew after five weeks or so without having achieved their objective, proving a significant victory for the Poles.

Someone with a small forge on the outskirts of Warsaw must be turning out the authentic-looking projectiles for the Scandinavian tourist trade, I speculated.

Though intrigued, I told Branko that I thought cannonballs available in that quantity and at that price had to be fakes. Someone with a small forge on the outskirts of Warsaw must be turning out the authentic-looking projectiles for the Scandinavian tourist trade, I speculated. Au contraire, exclaimed Branko.

His Danish military attaché colleague had taken one of the cannonballs back to Copenhagen to a government ordnance lab for evaluation. Its analysts told him that while there was no definitive way to establish the age of such metal objects, they had examined the interior structure of the projectile and found it to be the same as that of known Swedish cannonballs from the 17th century. If someone were producing fakes, they were going to a great deal of trouble to do so.

Branko’s explanation was good enough for me, so I bought one, which now sits on my desk at our summer home in Sweden (a homecoming of sorts?). On a subsequent trip to Warsaw, I purchased one for each of our two children. Though Gerd remains skeptical about the authenticity of my cannonball, I like to think that I own a small bit of Swedish (and Polish) history, as well as a happy memory of my friend Branko.

Afterword: In June 2019, Gerd and I visited Huseby Bruk, an ancient estate and museum located in south-central Sweden (Småland). We learned there that the bruk, or “works,” had begun smelting iron in 1629 and was a major manufacturer of canons and cannonballs for the Swedish military by the 1630s.

Thus, it is entirely possible, but in no way provable, that my cannonball, if authentic, was produced at Huseby, about an hour’s drive from Gerd’s hometown. Yet another twist in the saga of the Swedish cannonball.