The Real Heroes in Getting Out of Saigon: U.S. Foreign Service Officers

A young banker’s firsthand account of the unofficial evacuation when Saigon fell.

BY D.Z. STONE

Ralph White, author of the recently published memoir, Getting Out of Saigon: How a 27-Year-Old American Banker Saved 113 Vietnamese Civilians (Simon & Schuster, 2023), noticeably flinches when asked if he considers himself a hero. “The heroes,” White says, “were the Foreign Service officers [FSOs] who defied U.S. policy and their delusional ambassador, risking their careers and their own lives to evacuate thousands of at-risk Vietnamese who had worked for Americans. The only Vietnamese officially allowed to leave the country were intelligence assets and dependents of Americans.”

Indeed, if White had not chanced upon a clandestine evacuation program operated out of the U.S. embassy by a small group of FSOs without Ambassador Graham Martin’s knowledge, he never would have found a way out for the entire Chase Manhattan Bank Saigon staff and their families—113 people. “What’s interesting,” White notes, “is that getting everyone out was never part of my mission.”

During an evening-long conversation, I asked Ralph White about his Saigon experience. Remarkably, I had first met White more than 20 years ago at Columbia University and never had a clue until recently that he had saved these people.

A Temporary Assignment

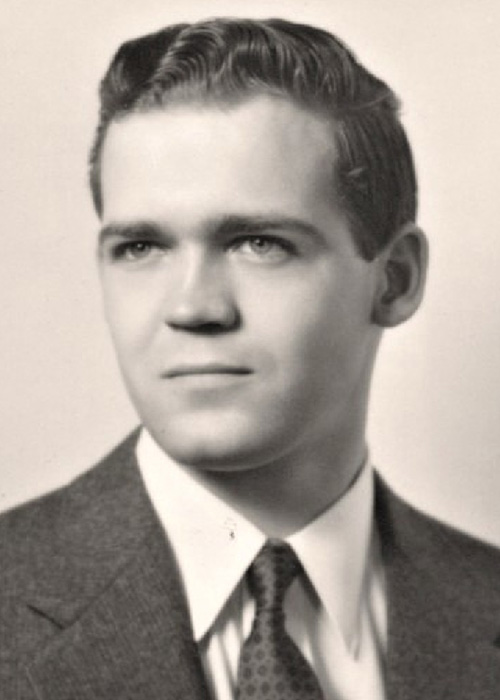

Shepard “Shep” Lowman.

1953 Harvard Law School Yearbook

White’s Saigon assignment began in mid-April 1975, just two weeks before the fall of the city, when he was an entry-level banking officer with Chase in Bangkok. Asked to temporarily head up the Saigon branch, this young man from a small New England town who enjoyed scuba diving, riding motorcycles, and piloting small planes welcomed the stint as an adventure. “I already knew the country and spoke some Vietnamese, thanks to my first job out of college, a year managing the American Express Bank on a military base in Pleiku.” White would replace Cornelius “Cor” Termijn, Chase Saigon’s country manager. Termijn was leaving while there were still daily Pan Am flights out. He feared if he stayed too long, his Dutch passport made it less likely the U.S. embassy would help him evacuate.

White was tasked with keeping the Chase Saigon branch open for as long as possible and to close it only if necessary: “I was told if I had to close, I was to contact the embassy for help in getting the four top bank officers and their families out of the country.” At first, he didn’t see any reason to be too concerned. “I was pretty casual about it. I was drinking beer and going to girly bars. I went to ‘Luau Night’ at the embassy. I really bought the bank’s story that eventually the embassy was going to help us.”

On his first full day in Saigon, April 15, 1975, White made his initial visit to the U.S. embassy. Termijn and John Linker, the Chase senior executive for Asia, went with the young banker to introduce him to the relevant U.S. diplomats. First, White met James “Jim” Ashida, the commercial attaché. When White asked about his banking counterparts, Ashida said both the Bank of America and First National City Bank had already pulled their American staff. “Not a comforting thought to be the last American banker in Saigon,” White later noted.

Next, White met Shepard “Shep” Lowman, the embassy’s political attaché. Both Termijn and Linker made it clear to Lowman that Chase wanted its Saigon branch to remain open as long as possible and didn’t want their employees to leave yet. They supported the ambassador’s position on this. They needed assurance, however, that the U.S. embassy would help evacuate their top banking officers, all Vietnamese nationals, when the time came. Lowman was direct: The embassy could not promise them that the U.S. government would help their Vietnamese Chase staff leave the country.

“I wondered what was going on. I didn’t quite understand,” says White. “Cor and Linker took it in stride, so I didn’t make a fuss. … At some point it became clear that the U.S. embassy was not going to be our friend. Ambassador Graham Martin and Deputy Chief of Mission Wolfgang Lehmann were both dead set against (a) the bank closing and (b) evacuating unrelated Vietnamese.”

White was tasked with keeping the Chase Saigon branch open for as long as possible and to close it only if necessary.

Because the Chase staff were “unrelated” Vietnamese—not married to or dependents of Americans—they did not qualify for the exit visas their government required to leave the country. Both Ambassador Martin and DCM Lehmann insisted on complying with South Vietnam’s stance on exit visas. However, as Lowman revealed, there were exceptions: Unrelated Vietnamese who were considered intelligence assets were being taken out of the country on CIA transports.

“If all they [Martin and Lehmann] did was slavishly adhere to the host country’s exit visa law, then they have a prima facie defense,” White explains. “The problem with this is they failed to recognize that the war was irretrievably lost, making early no-doc escape essential for all Vietnamese vulnerable to reprisal for their employment by Americans. They didn’t really care about those people who were intelligence assets. They cared about what they would reveal under torture.”

Stumbling upon a Secret

What White still did not know was that Shep Lowman, whose wife was Vietnamese, was running a clandestine program to help evacuate her family and the embassy’s doctor and 20 members of the doctor’s Vietnamese wife’s family—and who knows who else. “Why didn’t Lowman tell me? Well, if you’re running a secret evacuation operation under the nose of your ambassador, who refuses to face the reality that the war is over and there’s a need for evacuations, that’s not something you reveal to someone on first meeting. I eventually stumbled upon the clandestine operation when I started looking for ways to get Chase staff out,” says White.

Two days after his initial visit to the embassy, White had a message that Lucien Kinsolving, a first secretary, would like to speak to him. White went straight to the embassy.

“Have you met Ken Moorefield?” Kinsolving asked.

Moorefield, an aide to Ambassador Martin, headed up the new Evacuation Control Center (ECC) at Tan Son Nhat Airport. Every couple of hours, a C-130 would land to fly out Americans and their dependents as well as Vietnamese. The next day, White shared a taxi to the airport with Cor Termijn, who was leaving on a Pan Am flight from the civil aviation terminal. White let Termijn assume he rode along as a last chance to speak to the departing country manager. But he had another stop in mind, as well.

White knew that evacuating employees was impossible, so he told the vice consul they were his family.

Housed in a former gymnasium on the air base, the ECC was packed with former GIs looking to marry their Vietnamese girlfriends and adopt their children so they could get them out on Pacific Air Command military transports. “The ECC was the brainchild of idealist Harvard Law School graduate Shep Lowman,” says White. “It was a massive undertaking, brilliantly located, efficiently executed, and despite its veneer of propriety, its document requirements were ‘flexible.’ It was on the air base where there was nothing but an abandoned pool, abandoned bowling alley, and abandoned gym. When Ambassador Martin heard about it, I’m sure he heard control, and assumed its purpose was to prevent unauthorized evacuation, that exit visas were required. God bless Shep Lowman.”

Not finding Moorefield at the ECC, White went outside to explore. At Tiger Air, a commercial airline operating in Asia, he entered an unlocked DC-3 and considered “borrowing” the plane to fly himself and the top Chase banking officers and their families to Thailand. “I don’t know why I thought that was viable,” says White. “I had a pilot’s license to fly single engines and had only flown two-seat Cessnas and Pipers. I was young and quite confident that I could fly the cargo plane from Tan Son Nhat with Chase staff and families. But that would have killed us all.”

Later that evening, White went to the Chase Saigon offices to make sure the account settlement calculations were done. This is when he made an irresponsible promise. “Mr. Cuong, the deputy bank manager, was supervising a group of clerical workers,” White relates. “I knew they viewed me as David Rockefeller’s man who was going to get them out. Otherwise they’d have joined the refugee trails. They feared a retributive bloodbath for working for Americans.” One of the young women clerical workers asked White what would happen to them. Will he take them with him, or will they end up in a pile of dead bodies?

The words fell from White’s mouth. He said, “I’m not leaving without you,” then directed Cuong to make a list of all employees as well as the names of their spouses and children.

The next day he went to the U.S. mission warden’s office at the embassy to find out what short wave frequency they’d be using in an emergency. There he found the deputy warden typing Vietnamese names into a flight manifest. “That’s the first evidence I had that there was a clandestine program to evacuate undocumented Vietnamese. When I saw the flight manifest, I was stunned. It was totally by chance that I found out,” says White.

The Way Out

U.S. Army Captain Kenneth Moorefield (left) and his Vietnamese counterpart Captain Ngan. Moorefield was an Army captain in Vietnam when he was badly wounded. White says the Chase Manhattan Bank can be grateful that he then joined the U.S. Foreign Service.

Courtesy of Ralph White

So began White’s frantic effort to get the Chase staff out via the clandestine program. “There was new urgency as Xuan Loc had fallen, and the North Vietnamese Army was expected to enter Saigon in a matter of days,” he explains.

White’s quest led him to Colonel William Madison, head of the political section in the defense attaché office. Madison told White he would need military buses to get his people past the airport checkpoints. His advice was to get them on buses and into the airport, then shelter them at the ECC until exit policies were changed, which he expected would be soon. Madison warned White to be discreet about this, as Lowman was putting himself on the line.

On April 24, 1975, White got the call from Jim Ashida. He had 70 seats on a bus to the airport for Chase people leaving that night. Even though White needed more seats, 70 would cover the priority list Cuong had drawn up. He told Cuong, then followed procedure to close down Chase Saigon. White himself also needed to be on that bus because Pan Am was flying its last commercial flight out of Saigon that very day.

Once on the air base, White found a shady place for the Chase staff to wait and went into the ECC gymnasium. He got in a line for people without papers. The line ended at a table labeled “Vice Consul.” White knew that evacuating employees was impossible, so he told the vice consul they were his family. The vice consul asked if White was willing to take financial responsibility and make them his wards. White said yes, and the vice consul asked him how many. When White said 68, the vice consul handed him a stack of papers. White filled out a form for each Chase staff member.

“Ken Moorefield, standing behind the consul, took responsibility for the unconventional adoption,” says White. “I’ve received recognition for the rescue of my employees, but without Ken Moorefield’s ‘flexible’ interpretation of the regulations, they could all have been executed.”

Leaving the gymnasium, White ran into Ashida, who had another bus for the next day that could fit 70 more. Was White interested? He was. He left a bank officer in charge of the group at the airport and went back to Saigon. The remaining employees were notified they would leave the next day. At the ECC, White would do it again, filling out a form for each staff member. All in all, the 27-year-old adopted 113 people.

After spending a night sleeping on the ground, White and the second group left on April 26, 1975. On April 28, 1975, Tan Son Nhat Airport was bombed. Saigon fell on April 30, 1975.

After Saigon, FSO Shep Lowman worked with Vietnamese resettlement and became the State Department’s Deputy Assistant Secretary for Refugee Programs. He passed away in 2013. Ken Moorefield remained in the Foreign Service, rising in rank to become our ambassador to Gabon (2002-2004). From December 2005 to 2007, Moorefield served as senior State Department representative on the Iraq/Afghanistan Transition Planning Group. He subsequently joined the Department of Defense Office of Inspector General as Deputy General Inspector for Special Plans and Operations. In May 2022, Ralph White nominated Moorefield for a Presidential Medal of Freedom.

When sharing or linking to FSJ articles online, which we welcome and encourage, please be sure to cite the magazine (The Foreign Service Journal) and the month and year of publication. Please check the permissions page for further details.

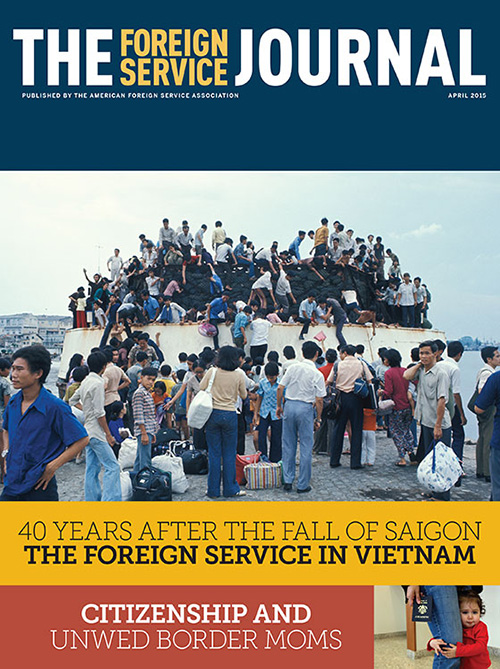

The Foreign Service in Vietnam

In addition to Lowman and Moorefield in Saigon, to save at-risk Vietnamese, a small group of FSOs also operated outside normal working channels at the State Department. In his 2015 piece for the Foreign Service Journal, “Mobilizing for South Vietnam’s Last Days,” Ambassador (ret.) Parker W. Borg detailed this under-the-radar effort.

According to Borg: “The core group included, Frank Wisner (Director for Management in Public Affairs), Paul Hare (Deputy Director of Press Relations), Craig Johnstone (Director of the Secretariat Staff), Lionel Rosenblatt (on the Deputy Secretary’s staff), Jim Bullington (who worked on the Vietnam desk and could keep us informed about desk-level actions) and myself (who had been working on Secretary Kissinger’s staff).”

Remarkably, two members of this group, Lionel Rosenblatt and Craig Johnstone, even flew to Saigon on their own to help save former colleagues. Borg says the men “stashed some 200 Vietnamese former work colleagues in vehicles, slipped them past Vietnamese security and pushed them aboard departing aircraft.”

The FSJ’s April 2015 special edition on the 40th anniversary of the fall of Saigon spotlights “The Foreign Service in Vietnam” and contains first-person accounts of the unofficial evacuation effort and other reflections from diplomats on the ground.

—The Editors

Read More...

- “On the Foreign Service in Vietnam,” The Foreign Service Journal, April 2015

- “Viet Cong Attack on Embassy Saigon, 1968” by Allan Wendt, The Foreign Service Journal, April 2015

- “Saigon Sayonara” by Joseph McBride, The Foreign Service Journal, April 2015

- “This 27-year-old American saved 113 Vietnamese civilians during the fall of Saigon” by Todd Farley, New York Post, May 2023