East Africa Embassy Bombings, 25 Years Later: Reflections from Ambassadors Prudence Bushnell and John E. Lange

Two ambassadors look back on what happened and what it means now.

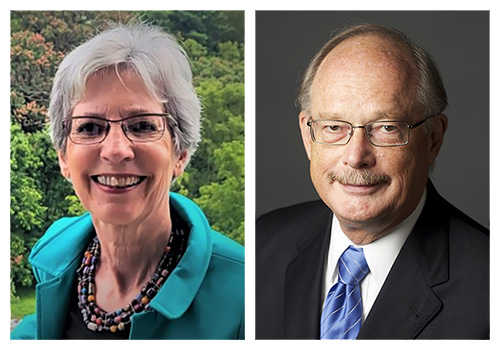

Ambassadors Prudence Bushnell and John Lange

A tragic anniversary is upon us. Aug. 7, 2023, will be 25 years since the al-Qaida terrorist bombing attack on the U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania.

To mark the 20th anniversary in 2018, the FSJ reached out to survivors and compiled reflections from 40 people who were on the ground in Nairobi or Dar when the unthinkable happened. Please return to those powerful stories in the July-August 2018 FSJ to better understand that seminal moment and the way the mission communities came together and carried on.

On the occasion of the 25th anniversary, we check back in with Ambassadors Prudence Bushnell and John Lange, distinguished retired career members of the Senior Foreign Service, who both contributed to the 2018 collection. Pru Bushnell was serving as U.S. ambassador to Kenya and John Lange as chargé d’affaires in Tanzania at the time of the bombings.

In a conversation with the Journal, they shared their thoughts looking back.

This memorial in Arlington National Cemetery honors the victims of the East Africa embassy bombings.

Patricia Wagner

FSJ: What do you think today’s generation of the Foreign Service should remember about the 1998 events and the people we lost and the survivors?

Ambassador Prudence Bushnell: There was a time when U.S. embassies were located on busy urban street corners, across from rail and bus stations, amid bustling commuters, hustling vendors, and awaiting visa applicants.

At mid-morning on Friday, Aug. 7, 1998, Osama bin Laden’s al-Qaida operatives detonated a thousand pounds of explosives in the rear parking lot of one such embassy, this one in Nairobi, Kenya. Minutes later another truck bomb exploded outside the gate of the U.S. embassy in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.

In Nairobi, 218 people were instantly killed: One hundred and seventy-two were neighbors or passersby. In the embassy, the dead included 46 colleagues: 34 Kenyans and 12 Americans.

The blast injured more than 4,000 people: 400 were severely disabled; 164 endured acute bone and muscle injuries; 38 adults and children were blinded; 15 were totally deafened; 75 suffered severely impaired vision; 49 were left with hearing disabilities. Hundreds of businesses were destroyed or damaged, many of them mom-and-pop stores with little or no insurance.

All this because they were near an American embassy that foreign terrorists wanted to destroy.

U.S. embassies are now housed in fortresses. Most are unbecoming and inconvenient. But they safeguard the neighbors, as well as the people inside.

Ambassador John Lange: The loss was enormous: More than 200 innocent people lost their lives, and thousands were injured, in simultaneous terrorist attacks aimed at two U.S. embassies. U.S. Embassy Nairobi, in a vulnerable downtown location with high-rise buildings, suffered the most. At U.S. Embassy Dar es Salaam, in a suburban location with low-rise buildings, 11 people died and more than 85 were injured.

The deaths included American, Kenyan, and Tanzanian Foreign Service personnel doing what the Foreign Service does every day: promote peace, support prosperity, and protect American citizens while advancing a broad range of U.S. interests in countries all over the world.

Twenty-five years later, the trauma of that experience still haunts the survivors and the families of those who died or were injured. Some still suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder. There are those who may be able to achieve psychological closure by putting such a tragic experience behind them, but for many of us the intense events of Aug. 7, 1998, are seared into our memories and cannot be forgotten or minimized.

Secretary of State Antony Blinken lays a wreath at the Nairobi memorial in 2021.

U.S. Department of State

FSJ: How have your thoughts about the 1998 bombings changed over time?

Amb. Bushnell: The August 7th Memorial Park, which we founded on the site of the former embassy, becomes increasingly meaningful. A green oasis on a busy street corner, it recognizes by name those who died and underscores the importance of peace and community. It is also, for me, the visible and culminating act of achievement of a traumatized and courageous Kenyan and American community that pulled itself out of the rubble, re-created its organizations, and helped one another to heal in the aftermath of a vicious terrorist attack.

We did not want the world to forget what happened, so we left our own mark. Every U.S. president who has come to Kenya has laid a wreath in front of the arched wall etched with the names of those who perished. Pole Sana (field of dreams).

As to thoughts about the bombing, the more I researched how it could have happened given the scrutiny that bin Laden and al-Qaida were under at the time, the more disturbed I became that I had been told by State Department colleagues to stop “nagging” about concerns of our embassy’s vulnerability just months before we were blown up. Weeks after the bombing, the world had moved on. Other than the mandatory Accountability Review Board dispatched by the Secretary of State, no after-action review or congressional hearing was held.

When al-Qaida struck the homeland three years later, the world forever changed. In the words of the 9/11 Commission: “The tragedy of the embassy bombings provided an opportunity for the full examination across government, of the national security threat that bin Laden posed. Such an examination could have made clear to all that issues were at stake that were much larger than the domestic politics of the moment.”

The title of the book that resulted from my research became Terrorism, Betrayal, and Resilience: My Story of the 1998 U.S. Embassy Bombings (2018).

We did not want the world to forget what happened, so we left our own mark.

—Ambassador Pru Bushnell

Amb. Lange: The single biggest day that affected me since the 1998 bombings was 9/11, when al-Qaida attacked the U.S. homeland. Those attacks brought back all of the terrible memories from 1998 combined with anger. Al-Qaida had planted a truck bomb beneath the World Trade Center in February 1993, bombed two U.S. embassies in 1998, and set off explosives next to the USS Cole during its fuel stop in Yemen in 2000. Why hadn’t the U.S. government taken the threat posed by Osama bin Laden more seriously and done more to prevent him from ever again attacking the United States?

In email exchanges on 9/11, survivors of the Dar bombing described themselves as “dysfunctional” and “incapacitated.” We were reliving the trauma. The day 9/11/2001 deeply affected those of us who had survived 8/7/1998.

Fittingly, commemorations of the East Africa embassy bombings continue to this day. I was pleased that Vice President Kamala Harris, during her March 2023 visit to Dar es Salaam, went to the Hope Out of Sorrow memorial at the National Museum of Tanzania to honor the victims and shook hands with staff who had been present during the attack.

Every Aug. 7, at 10:30 a.m., many of the survivors of the Nairobi and Dar bombings and their families assemble at Arlington National Cemetery at the memorial plaque dedicated to those who lost their lives in the embassy bombings. The gathering brings back painful memories but also reinforces our bonds of friendship and community from shared experiences.

One of two permanent exhibits at the Dar es Salaam memorial honoring victims of the 1998 East Africa embassy bombings.

Vivian Walker

FSJ: What should we learn (or have learned) from this tragedy?

Amb. Bushnell: The importance of leadership. On Aug. 7, survivors of the blast who made it out of the building regrouped on the front steps and returned as first responders. Our medical team set up triage on the glass-strewn sidewalk, using good Samaritans to send the most severely wounded to the hospital. Kenyan colleagues from USAID formed teams with Americans to scour neighborhoods, hospitals, and morgues for the missing. USAID drivers formed an emergency motor pool that ran for the next 10 months. Others initiated the emergency task force. No one waited to be told what to do; we did what was necessary.

Take care of your people, and the rest will take care of itself. These words that Don Leidel, a mentor, wrote when I became chief of mission popped into my brain the day after the bombing. I could see a stalwart community taking care of everything from storing bodies for the FBI to initiating medical and death claims for grieving families. My job was to take care of them. That meant asking the right questions, actively listening to answers, eliminating obstacles, and securing resources.

Amb. Lange: At all levels: Take care of our people, take care of security, and prepare for the unexpected.

As I wrote in a March 2001 Foreign Service Journal article, “Crisis Response: The Human Factor,” American Foreign Service generalists and specialists, locally employed staff, and family members all have a huge impact on crisis management and embassy security. That makes personnel recruitment and retention vitally important.

There are many aspects to taking care of people, but one that comes to mind in this context is the importance of recognizing and dealing with the lingering effects of such devastating events on active and retired personnel and their family members.

On security, we knew that U.S. Embassy Dar es Salaam had vulnerabilities, including an antiquated building with a 30-foot setback. But it was considered a low-threat post, and we had no advance warning of the devastating attack. Many new, and much more secure, embassies have been built since 1998. But for anyone serving abroad, it is important to be vigilant and not to make assumptions about security, no matter where one is stationed.

For anyone serving abroad, it is important to be vigilant and not to make assumptions about security, no matter where one is stationed.

—Ambassador John E. Lange

And one needs to be willing to take on responsibilities that were never anticipated. In the immediate aftermath of the bombing in Dar, Foreign Service personnel and their family members valiantly took on roles they were never expected or trained to do: arranging hospital visits and medical evacuations for those who were badly injured; running the airport operation for the planeloads of people and assistance that arrived; finding hotel rooms for hundreds of temporary duty personnel; giving up their residence so we could establish a temporary embassy; organizing a commemorative ceremony for our colleagues who had died; working with the Tanzanian government to help the FBI pursue its investigation; and much, much more.

Finally, I have my own message for deputy chiefs of mission: Do not assume when you serve as chargé d’affaires that you are just a caretaker until the ambassador is present in-country. I was a mid-level officer assigned to be DCM, but I served as chargé in Dar es Salaam from my arrival in December 1997 until the arrival of the new ambassador in mid-September 1998. I never anticipated having to lead an embassy following a devastating and deadly bombing, but that leadership role fell upon me—and the American and Tanzanian staff and family members responded heroically. DCMs need to be well trained and well prepared.

When sharing or linking to FSJ articles online, which we welcome and encourage, please be sure to cite the magazine (The Foreign Service Journal) and the month and year of publication. Please check the permissions page for further details.

Read More...

- “1990s—Prelude to a Disaster” by Prudence Bushnell, The Foreign Service Journal, March 2014

- “The Bombing of U.S. Embassy Dar es Salaam, Tanzania,” ADST, July 2016

- “A Day of Terror: From the FSJ Archive,” The Foreign Service Journal, July-August 2018

- “Reflections on the U.S. Embassy Bombings in Kenya and Tanzania,” The Foreign Service Journal, July-August 2018