A Day of Terror: From the FSJ Archive

The following are selected excerpts from articles, columns and letters to the editor on the East Africa bombings over the years since 1998.

Preventing More Needless Deaths

At Washington area Metro stations, they now play an airportstyle announcement asking passengers not to leave bags or parcels unattended, due to “recent international incidents.” It is another striking example of how events abroad affect the daily lives of Americans at home. In the Foreign Service, our mission is to shape and manage those events. We cannot achieve our mission unless we can work in safety.

In the aftermath of the tragic embassy bombings in Nairobi and Dar es Salaam, AFSA has been working to bring this message to the administration, the Congress and the American people. Our central theme is: Never Again. Many of us remember how much more attention we gave security issues following the 1983 embassy bombings in Beirut. Those murders taught us that you lose the struggle for peace if you can’t protect your diplomatic troops.

As memories of Beirut faded, interest in security waned. So did funding. …As this issue of the Foreign Service Journal goes to press, we are awaiting the administration’s funding request. AFSA has one final message on impending security upgrades: focus on people. We need to invest in human capital also. That means providing adequate training for our employees so that they are better prepared to deal with security matters.

—Dan Geisler, AFSA president, from “President’s Views,”

FSJ, October 1998.

Who’s Responsible for Embassy Security?

October 1998 FSJ.

In the wake of the embassy bombings in East Africa Aug. 7, many journalists have been asking why those buildings, especially the Nairobi embassy, were so vulnerable.

CNN revealed Aug. 13 that U.S. Ambassador to Kenya Prudence Bushnell had warned the State Department in cables sent in December 1997 and April or May 1998 that embassy security in Nairobi needed to be upgraded.

One of Bushnell’s cables said, “The location is problematic, always has been. It’s in one of the busiest streets in Nairobi, the intersection of two major streets.” In December [1997] Bushnell told Washington she needed a new embassy.

CNN reports that a team from Diplomatic Security visited the Nairobi embassy last year and agreed its location was far from ideal. But on June 1 [1998], Bushnell got a written reply from Under Secretary for Management Bonnie Cohen.

CNN reports that Cohen wrote, “In light of the current threat level and comparative recent construction of the building, a new building was ranked low in relative priority to the needs of other embassies.”

—From Clippings, FSJ, October 1998.

Through Terrorists’ Eyes

On Friday, Aug. 7, President Clinton vowed to hunt down those responsible for the bombings of our embassies in Nairobi and Dar es Salaam. “No matter what or how long it takes,” he said. But can we Americans—and especially the relatives of those who died in the attacks—hope that this time we will respond more effectively than before?

We should use our imagination. Put ourselves in the shoes of those who want to hurt and humiliate us. In Beirut and al-Khobar, the threats and dangers were visibly present. Our viewers, however, were unable really to see them. So it’s not just more information that we need, but rather the ability to look at it afresh, to place our data in a new series of relationships, to undergo a transposition of the mind. And I wonder: might it even be especially difficult for our carefully screened diplomatic and security professionals to apprehend, really to imagine, threats from sources so weird, so distant from their intellectual and social coordinates?

—Hume Horan, retired ambassador, Washington, D.C.,

from his Letter to the Editor, FSJ, October 1998.

USAID and Terrorism

The Nairobi and Dar es Salaam attacks have taken their terrible human toll. Programs and actions are proposed by all—State Department, FBI, White House, Congress.

Still, it seems like the cowardly and inhuman attackers have stripped common sense from those who should have learned from similar terrible tragedies of the past. Reportedly, the embassy in Cairo is closing the separate USAID office and moving it into the embassy. This will result in improved security? For whom?

The very nature of USAID’s work (as well as some embassy tasks) cannot be conducted from a secure fortress and to attempt to do so will hobble the agency.

The ambassador and the embassy are the symbols of our nation overseas and need to be protected. But don’t, in the name of security, subject all official Americans to the same constraints and restrictions. We all recognize that some risks and insecurity are a necessary part of a foreign affairs career.

—Arthur M. Handly, retired FSO, USAID, Port Kent, N.Y.,

from his Letter to the Editor, FSJ, October 1998.

Going Home

Tribute

Names can fade over time

for tomorrow brings new

victims and villains.

Yet we will never forget the

impact made through

your service.

The tears of a shocked nation

shed in honor to you—

Our precious sacrifice to a

cowardly aggressor.

May God embrace you as you

return home with the

prayers of a grateful nation.

—Daniel Fowler, AFSA associate member, Old Orchard Beach, Maine, from FSJ October 1998.

As the flag-draped caskets of the American staff killed in the embassy bombings in Africa were carried from the Air Force plane, a military band played the “Going Home” theme by Dvorak. The music seemed especially appropriate since these colleagues were going home for the last time. Along with hundreds of others, I had come not only to mourn, but also to show how proud I was of those colleagues who had given their lives for our country.

While standing in that crowd, I thought how little those watching this event on television knew about what we in the Foreign Service do. Our work is little understood and therefore distrusted by both political parties, each of which sees us in league with the other. Yet both parties will agree that we are responsible for every perceived foreign policy blunder. We are an easy target because we have no broad American constituency.

There is AFSA, and there are our families and friends to speak up for us. As retired FSO David T. Jones wrote in a letter printed on the editorial page of the Washington Post on Aug. 15, 1998: “It is bitterly amusing that the only time Foreign Service personnel are noticed by the American public and Congress is when we are murdered or held hostage.”

—Riley Sever, USIA vice president,

from his AFSA News column, FSJ, October 1998.

A Grateful Nation Mourns Its Dead

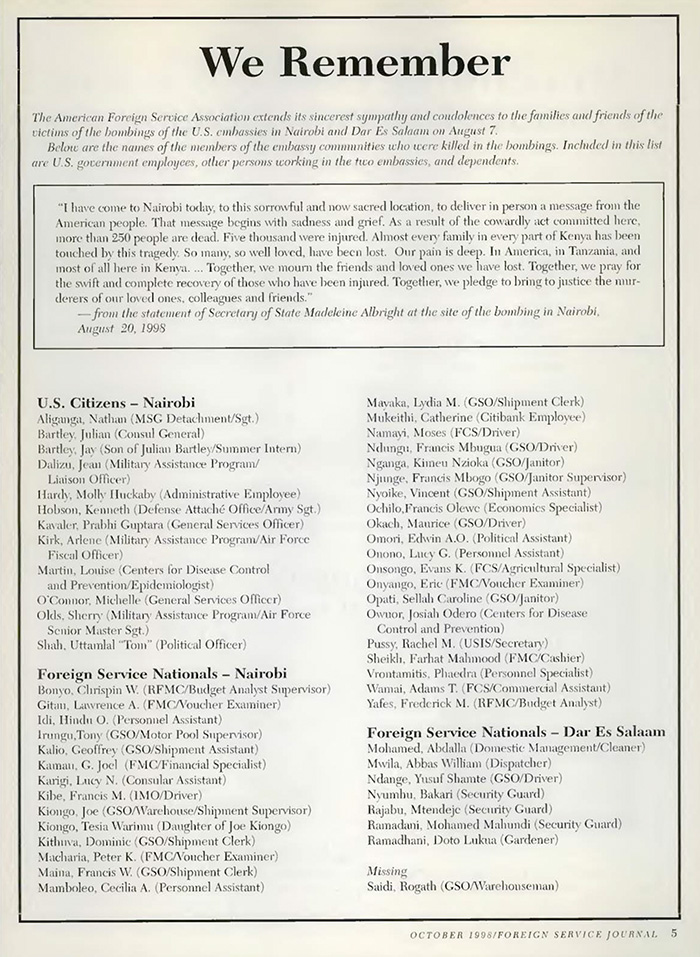

On Thursday, Aug. 13, President [Bill] Clinton led over a thousand mourners—members of the Cabinet, the Congress, the diplomatic community and the armed forces; friends and colleagues from America’s foreign affairs agencies; and family members—in a tearful tribute to the 12 American victims of the terrorist bombings in Kenya and Tanzania.

President Clinton and Secretary [Madeleine] Albright also honored the Foreign Service National employees who perished protecting American interests in Kenya and Tanzania, as well as private citizens of both countries who were killed.

After the ceremony, William Harrop, an AFSA board member and a former U.S. ambassador to Kenya, stated that everyone there, whether they were part of the foreign affairs agencies or not, felt a loss. He noted that more people now understand that diplomacy is a high-risk profession.

The Department of State sent a cable to all diplomatic and consular posts requesting donations to support our Foreign Service Nationals (FSNs) who suffered in the bombings. FSNs are an essential part of our foreign policy team, often risking their personal safety to promote America overseas. Many of those FSNs who died were the sole supporters of large extended families.

These families do not have the survivor benefits available to American victims. Contributions qualify as a charitable deduction for federal income tax purposes.

—Frank Miller, USAID vice president,

from his AFSA News column, FSJ, October 1998.

Protecting Americans Overseas

After the bombings, the Secretary of State convened an Accountability Review Board to investigate the bombings and make recommendations for improving essential security for overseas missions. Chaired by former Ambassador and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Adm. William J. Crowe, the ARB reported a “failure by several administrations and Congresses over the past decade to invest adequate efforts and resources to reduce the vulnerability of U.S. diplomatic missions around the world to terrorist attacks.” It stated the United States must spend $1.4 billion per year for the next 10 years to upgrade facilities and training.

The ARB made clear in its report that the security situation is getting worse, not better: “The emergence of sophisticated and global terrorist networks aimed at U.S. interests abroad have dramatically changed the threat environment. In addition, terrorists may in the future use new methods of attack of even greater destructive capacity, including biological or chemical weapons.”

The administration should commit itself now to meeting Adm. Crowe’s recommendations, and the Congress should support it.

—Marshall P. Adair, AFSA president,

from “President’s Views,” FSJ, November 1999.

Eyewitness to Terror: Nairobi’s Day of Infamy

July-August 1999 AFSA News.

The rough outline of what happened is easy to relate, but how can one render the texture of the events? All those who lived through the bombing own their own piece of the hell that called on us that day—a compound of the specific sights, sounds and smells each of us had seared into our memories, and of the emotions they stirred.

With the first rescue operations set in place, I walked to the rear of the building where the bomb had gone off to assess the damage there. It was a scene Dante might have conjured for his Inferno. The whole back side of the chancery was rubble. In the back parking lot the wrecks of several vehicles were ablaze. Charred corpses, black and shriveled, their hands outstretched in what looked like a last, futile supplication to ward of their demise, were strewn about. Hundreds of survivors were struggling out of the towering Cooperative Bank building behind the chancery. All that was left of a smaller building that flanked it was a heap of concrete slabs. One man staggered by silently, the left side of his face ripped away, strips of flesh hanging from his bones. …

How does it appear to me today? Muted pain lingers on. You carry on, absorbed by the kaleidoscope of daily life, but part of you cannot forget. The memories force themselves upon you when they choose.

It would be untrue, however, to claim that my memory of August 7, 1998, is entirely a shade of black. Tinged with the sorrow is pride, as I recall the extraordinary spirit our mission members, Kenyans and Americans alike, few of whom had any preparation for such a disaster, displayed in the face of danger and death. The examples are almost innumerable. Who can forget the teams of volunteers who went repeatedly back into the blasted building, by then a death trap, filled with blinding and, we feared, poisonous smoke, littered with live wires, with gaping holes where elevator shafts once were? Ignoring the danger that the wrecked chancery might collapse, they worked tirelessly to remove the wounded and the dead.

—Lucien Vandenbroucke, politcal counselor and acting DCM

in Nairobi on Aug. 7, 1998, from his article by the same title in the

“Focus on Embassy Security,” FSJ, June 2000.

Memorial to East Africa Bombing Victims

A headstone-sized memorial now stands at Arlington National Cemetery in honor of the 221 Americans, Kenyans and Tanzanians who were killed in the August 7, 1998, embassy bombings in Nairobi and Dar es Salaam. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright, the chargés from the embassies of Kenya and Tanzania, and some 100 others, including representatives of all the federal agencies that lost employees or family members, participated in the May 19 dedication at Arlington. John Naland, AFSA State vice president, and Frank Miller, AFSA USAID vice president, also attended the ceremony.

—From AFSA News, FSJ, September 2000.

Horror and Heroism

Lucien Vandenbroucke’s account of the Nairobi terrorist bombing (FSJ, June 2000) accurately described the horror and heroism of “Black Friday.”

We, the survivors, are doomed to relive Aug. 7 every day of our lives. Let’s not let the bombings suffer from the same “old news” syndrome that prevented us from fully implementing the Inman proposals in the 1980s. I suggest that future discussions on security and openness include at least one survivor from a major bombing as a reality check.

I am also proud to be a member of the Foreign Service community, which reflects the ideals of America overseas. On Aug. 7, 1998, Ambassador Prudence Bushnell offered immediate evacuation to any direct-hire American employee in Nairobi. No one departed.

—W. Lee Reed, security engineering officer, Nairobi Search and

Rescue Team leader, Embassy Pretoria, from his Letter to the Editor,

“Eyewitness to Terror,” FSJ, November 2000.

Crisis Response, the Human Factor

In the period since the Aug. 7, 1998, embassy bombings in Kenya and Tanzania, much has been written about security at U.S. embassies and consulates. There is one element, however, that seems to be underestimated in many of the discussions of improvements in crisis management and embassy security: their fundamental link to personnel recruitment and retention.

Foreign Service personnel frequently talk about the need to recruit the best and the brightest from a diverse group of Americans, and there have been numerous efforts over the years to improve the hiring process (making the written examination a better test of skills actually used on the job, shortening the lengthy hiring process, etc.) in order to win the war for talent. There is no simple solution, but our experience in Dar es Salaam shows how much having the right team in place matters.

The foreign affairs agencies can spend lots of time debating foreign policy, formulating mission performance plans and drafting emergency action plans. But perhaps the single most underrated function within those agencies, from which all else follows, is to recruit and retain the very best people available. When a crisis occurs, we cannot manage with anything less.

— John E. Lange, chargé d'affaires at Embassy Dar es Salaam

on Aug. 7, 1998, from his Speaking Out column

by the same title, FSJ, March 2001.

Reflecting on the Unthinkable

In 1998, it was a scene of implausible devastation. Today, it is a place for quiet contemplation. But at its dedication on the third anniversary of a terrorist bomb that killed 219 [sic] people and injured more than 5,000, the August 7 Memorial Park—on the former site of the U.S. embassy in Nairobi, Kenya—was the focus of both reflection and frustration.

Thousands gathered to remember the 207 [sic] Kenyans and 12 Americans who died in the bombing, for which four followers of Islamic militant Osama bin Laden were extradited to New York and convicted. The official dedication ceremony, led by Kenya’s president, Daniel arap Moi, went off without a problem, but when Moi and his entourage left, the crowd—too large to be accommodated within the park—surged forward against the fences, temporarily trapping U.S. Ambassador Johnnie Carson. Carson was pulled to safety as the crowd trampled over the security barriers.

Moi was joined at the ceremony by Prudence Bushnell, who was U.S. ambassador to Kenya at the time of the bombings and is currently ambassador to Guatemala. He said that the bombing demonstrated “in a most crude and violent manner” that peace is a fragile entity that should not be taken for granted. For her part, Bushnell acknowledged the frustrations that still exist: “I want to say to you again, as a fellow human being, pole sana”—Swahili for “very sorry.”

The U.S government has provided more than $42 million in indirect aid—primarily school fees and medical care—to victims and their families. The aid is soon to end, though, and that angers Kenyans who feel that Washington should take responsibility for the attack. “We suffered because of America,” one man who lost an eye in the blast told The New York Times.

—From Clippings, FSJ,

October 2001

On Mary Ryan’s Role after the 1998 Embassy Bombings

It is with great fondness that I read Edward Alden’s article, “Remembering Mary Ryan,” in your June issue. I felt, however, that it did not do full justice to this incredible public servant. So I would like to offer an additional perspective on Ambassador Ryan’s response to the 9/11 attacks, as well as her role following the August 1998 embassy bombings in Kenya and Tanzania.

Though Alden’s article makes a passing mention of the 1998 bombings, it does not show the true impact this dreadful moment had on our Foreign Service and our institutional family, including Amb. Ryan.

In the immediate aftermath of the bombings, Amb. Ryan, then assistant secretary for consular affairs, flew to Nairobi, put on a hard hat and climbed through the rubble, asking for the name and background of each victim, American and Kenyan alike. She carried these moments with her to the day of her passing— whether working nonstop in the aftermath to improve the security of our embassies worldwide; demanding a more compassionate outreach to the department’s most valuable assets, its employees; or testifying to Congress on the need for more information sharing within our own government.

I was the financial management center director for Embassy Nairobi at the time of the bombings, and I lost nine of my staff on that dreadful day. Mary Ryan did not know me before that ordeal, but she put her arm around me, literally and figuratively, to help me cope with this life-changing tragedy. She showed similar concern for my colleagues, including Foreign Service National employees. And she worked tirelessly to prevent another attack. So when 9/11 occurred, she was enraged.

—Michelle L. Stefanick, Foreign Policy Adviser, Marine Forces

Europe and Africa, Stuttgart, Germany, from her Letter to the

Editor, “For the (Congressional) Record,” FSJ, October 2010.