Reflections on the U.S. Embassy Bombings in Kenya and Tanzania

On the 20th anniversary of the terrorist attack on two U.S. embassies, American, Kenyan and Tanzanian survivors reflect on that seminal event and its aftermath.

Editor’s Note: In honor and commemoration of the 20th anniversary of the Aug. 7, 1998, East Africa embassy bombings in Nairobi and Dar es Salaam, we asked American, Kenyan and Tanzanian survivors to reflect on that seminal event and its aftermath, and to share thoughts on carrying on after tragedy.

With guidance from Ambassadors (ret.) Prudence Bushnell and John Lange, we posed a set of questions to as many embassy staff and family member survivors as could be found through their informal networks:

• When the attack occurred, I was (where, when, what happened);

• The Aug. 7 bombings most affected me (my family and colleagues) in the following ways;

• This is what helped as I created a new normal for my life;

• Given what I have learned, I would like to pass on the following advice for those who may become survivors and helpers in the future.

Some chose to fill in those blanks; others chose a different format. What follows is a compilation of the responses. (Light editing and some trimming of text was done as needed.)

Each author’s name is followed by the position he or she held at the time of the bombing.

This FSJ collection is just one part of a collaboration between AFSA, the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training and the U.S. Diplomacy Center to collect reflections, photos and artifacts for the 20th anniversary of the East Africa bombings.

ADST will continue to collect reflections, so we encourage those who either were not contacted or did not have a chance to respond, to submit something for the permanent Oral History Collection. Send 500 to 1,000 words in response to the questions above to oralhistory@adst.org, or call (703) 302-6290 for more information.

The USDC continues to collect artifacts for its permanent collection. To donate an item, please email a description to Associate Curator Kathryn Speckart at speckartkg@state.gov, or call (202) 472-8208.

On Aug. 6, USDC will host an event open to the public marking the anniversary. A panel of Tanzanian, Kenyan and American survivors sharing their stories, discussion and an exhibit will be featured. All attendees will receive a copy of this Journal collection. On Aug. 7, survivors will gather at the memorial marker in Arlington National Cemetery.

Thanks to all those who shared their experiences. We know that for some it is still incredibly painful to do so, while for others it is cathartic, and for many it lies somewhere in between.

–Shawn Dorman

NAIROBI, KENYA

The Practice of Leadership at Every Level

Prudence Bushnell

U.S. Ambassador to Kenya

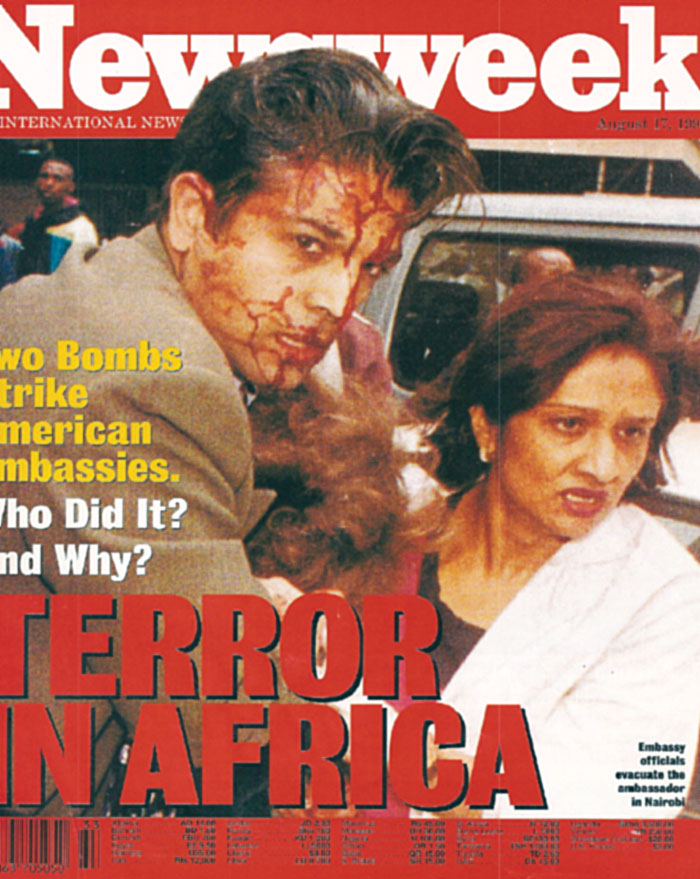

Commercial Officer Riz Khaliq and a nurse from the emergency medical unit at the embassy take injured U.S. Ambassador Prudence Bushnell to safety following the bombing of Embassy Nairobi.

I was into my second year as U.S. ambassador to Kenya. With two colleagues from the Commerce Department, I was meeting with the Kenyan minister of commerce to discuss the visit of an American VIP trade delegation. We were on the top floor of a high-rise building on the other side of the parking lot from the embassy. The sound of an explosion attracted many to the window; I was among the last to stand up.

A huge bang with the weight of a freight train bore through the room, throwing me back. The building swayed; I thought I was going to die. I blacked out for a moment, came to and descended the endless flights of stairs with a colleague. Only when we exited the building did I see what had happened to the embassy. I realized in an instant that no one was going to take care of me, and I had better get to work.

After leaving my injured colleagues in the care of medical help, I went to the Crisis Control Room that had been quickly set up at the USAID building. We were a large mission with competent, experienced people throughout the ranks. Colleagues had already set up communications with Washington. I saw the practice of leadership at every level of our wounded organization and community; it got us through the next 10 months, when I departed post.

Our building, our organization, our community and our neighborhood were blown up. As ambassador, I was responsible for security; and while I had pushed and pushed to get Washington’s attention to our vulnerabilities, I remain keenly aware that I failed. Hours after the attack, as my attention was pulled in multiple directions, I remembered the advice of a mentor: “Take care of your people, and the rest will take care of itself.”

I did so as well as I could. I discovered a depth of sadness and breadth of anger I did not know I had. I also learned I could not take away anyone else’s pain, trauma, anger or sadness, but I could accompany them. I could also promote an environment in which leadership, healing and achievement were possible.

Every individual in our community responded differently. The diversity of reactions created a pace that helped us both to remember and to move forward. It also caused tension between the people who felt we were moving too fast or commemorating too much.

Creating a New Normal

These are the things that helped me in the aftermath: My husband Richard Buckley and Office Manager Linda Howard were with me from the start. Not only did they help me to cope in the immediate aftermath, but they enabled me to face new and challenging FS assignments for the next six years.

Community helped. The kindness and forgiveness of families who lost loved ones helped. The trust, competence and teamwork people demonstrated helped us literally move on from the rubble. The support of family and friends, even if far away, provided a bridge to what “normal” looked like.

Work and time helped. I had meaningful work to accomplish that built on the leadership experience from Nairobi. Better understanding and talking about what happened gave meaning, while the passage of time gave comfort.

Healthy habits for body, mind and soul helped. These included gardening, walking, knitting, reading and cultivating friendships.

Therapy helped. It was not until I retired seven years after the bombing that I tended to my symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder, using somatic therapy (EMDR), which I found helpful.

What I Learned

I would like to pass on the following advice for those who may become survivors and helpers in the future.

• Get involved in the community and help to grow teams that learn how to do things together. This will be essential in catastrophes and highly satisfying otherwise.

• Be kind to yourself, and be kind to one another.

• Take care of your people—and take care of yourself, too.

• Allow spouses, family and friends to take care of you.

• Seek professional help to stay resilient.

• To help after a crisis, be clear about your mission and adapt to reality.

• Build a bridge between “we” and “they” to create the trust that will make recovery easier.

• Don’t expect this to end any time soon. Catastrophes breed crises, and some go on for years.

• Find meaning in the event—the “treasures among the ashes.”

• Do not depend on the media or our political leaders to keep the story alive or create change; both have short memories.

• Remember, it will get better.

The Very Worst Moment in My Life

Howard Kavaler

Permanent Representative of the United States to the United Nations Environment Program

At approximately 10:15 a.m. on Aug. 7, 1998, I saw my wife, Prabhi Kavaler, for the very last time.

I told her that prior to meeting her for lunch (she worked in the embassy as an assistant general services officer), I would go to the Community Liaison Office in the front of the chancery to see if they knew when the school bus would come the following Monday to pick up our two young daughters for their first day of school at our new post. Prior to going to the CLO, I stopped into my office to save a cable that I was drafting.

On arriving at the CLO, I heard a loud sound, followed some 10 seconds later by an even louder noise. The ceiling started to collapse on us, and the chancery was enveloped in darkness. Through clouds of dust, dangling wires and debris, I searched for Prabhi where I thought her office was once located.

I could not find Prabhi, and she did not emerge from the embassy. I finally got a ride to our temporary quarters, where I told my two daughters, 10-year-old Tara and 5-year-old Maya, that in all likelihood their mother had been killed in an explosion at the embassy. That remains the very worst moment in my 69 years.

Having packed our bags, my longstanding housekeeper, the girls and I went to the home of our very good friends, Steve and Judy Nolan. Sometime during our stay, Ambassador Bushnell visited to express her condolences to me. Shortly after receiving the formal notification of Prabhi’s death, my daughters, housekeeper and I were driven from the Nolans’ residence to Jomo Kenyatta Airport, where we boarded a flight that was the first leg of our journey back to the United States.

Take Care of Your Family and Your People

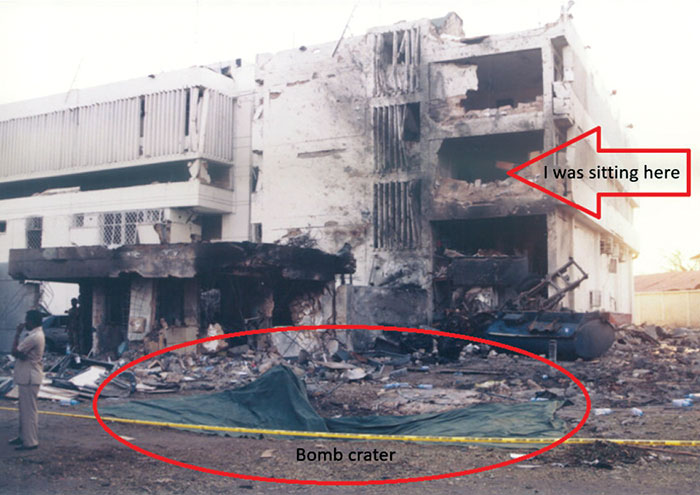

Paul Peterson

Regional Security Officer

On the morning of Aug. 7, I was sitting in one of my first Country Team meetings, having arrived at post in mid-July to assume the duties of the regional security officer. The meeting was being held on the fourth floor of the chancery in the ambassador’s office. The acting deputy chief of mission was presiding, as the ambassador was out of the building for a meeting.

We were discussing the security briefings that my staff provided to incoming employees—information on Nairobi’s critical crime threat could be disconcerting to new arrivals, and the question was whether we could tone it down. A few minutes into this conversation, the windows on the back wall of the office blew in, throwing members of the country team from their chairs to the floor and showering us with debris.

In the wake of the explosion came an eerie silence, lasting several seconds. I was struggling to crawl over some of my colleagues and head downstairs to Post One to find out our status, when I heard the screaming of people in pain and horror.

As I found my way down the darkened stairwell, I realized two things: We had been seriously damaged by an apparent attack, and this wasn’t going to help me lighten up my briefings. Panicked employees, some whole, many injured, poured into the stairwell. I assisted several injured employees down the stairwell to what had been the lobby and turned them over to other employees.

At our heavily damaged Post One I met with the Marine Security Guard detachment commander to conduct a damage assessment, establish a secure perimeter, search for survivors, evacuate and triage the wounded and begin to address the hundreds of other details that managing a mass casualty event requires. The gunny and I conducted a quick survey of the damage and began to develop a perimeter security plan. We were trying to manage chaos.

Once our initial survey was completed, we held an impromptu Country Team meeting in front of the ravaged building and delineated responsibilities. We knew we had lost people, some of them close to us; but our priority at that point was to try to ensure we didn’t lose any more, either through another attack or an accident during our rescue efforts inside the building. We spent the next 40 hours trying to make that happen.

People deal with stress differently. Not everyone can deal with a tragedy of this magnitude and continue to operate effectively. —Paul Peterson

I’ve realized, with perspective, that the courageous deeds and acts of kindness and compassion I witnessed far outweigh the pain and loss we had to address. I take immense pride when I look back at the many obstacles we addressed and overcame.

I trained for most of my life as a first responder, prepared to address crisis situations and other emergencies. Over more than 20 years I had acquired considerable experience addressing stressful situations, but had never given much thought to how my job affected my family. Nairobi taught me that my family paid a price for my choice of profession. Due to a bombingrelated failure in communication, it was several hours before many family members, mine included, were aware of whether we were victims or survivors, injured or whole.

In the hours waiting for news, families gathered together, shared what little information was available and hoped for the best. I later learned that, but for a last-minute change in plans, my wife would have been in an area of the chancery in which there were no survivors after the blast. My colleagues could share comparable stories.

As I created a new normal for my life, I did my best to take the positive aspects of my Nairobi experience and use them to become a better husband, father and professional. I still live with some of the negative images, but I’ve managed to maintain perspective. I’ve dedicated myself to the principle that there’s nothing more important than taking care of your family and your people, and I do my best to live up to that.

The examples of leadership in crisis by Ambassador Prudence Bushnell, Deputy Chief of Mission Michael Marine and the Country Team demonstrated the highest standards of the Foreign Service and the other U.S. government agencies that were present. The political lesson: U.S. government and Foreign Service National employees deserve the highest levels of protection when representing the United States overseas.

People deal with stress differently. Not everyone can deal with a tragedy of this magnitude and continue to operate effectively. Early screening of employees by professional medical and psychiatric professionals should take place in the wake of any major security incident or other disaster, to determine how people are coping and if a change in environment would be beneficial.

Prior to 1998, the Department of State had failed to effectively address the myriad security issues that had been brought to their attention. However, as a direct result of the Nairobi and Dar es Salaam bombings, it developed and enacted new procedures, and many new embassies and consulates have been built to stricter security standards, saving lives. We must continue to fight complacency.

Navy Seabees remove rubble from one of the many destroyed offices in the embassy building. Following the blasts, more than 40 Seabees were deployed to Kenya and Tanzania to assist with the investigations and cleanup operations.

Courtesy of Worley and Joyce Reed

Helping Others Gives Purpose

Joyce Ann Reed

Administrative Assistant for Communications

I was in the Communications Center hallway on the top floor, escorting a member of the Kenyan char force who was doing routine cleaning. I heard a loud crash on the roof, and then there was total darkness. I was having trouble breathing. I saw debris all over my clothes and in my hair when the emergency lights came on.

Once the door to the ambassador’s office was unlocked, I took the Kenyan employee’s hand and led her through it, then out of the bombed building to safety. I immediately turned our car into an ambulance, loading bleeding Americans and Kenyans to be taken to the hospital. I also helped with the triage that was being organized by our doctor, Gretchen McCoy. In the afternoon, I went to the USAID building to help with the reorganization of the American embassy.

The effect the bombing has had on me in the long term is that I do not feel safe anymore, no matter where I go. I experience painful feelings when I have flashbacks of the bombing. These flashbacks can be triggered by certain sounds, smells or just seeing or hearing about other similar events. The bombing damaged my husband’s life as well, since he was one of my co-workers at the embassy. Our children’s lives were forever changed.

I take medication given to me by my psychiatrist, whom I see monthly for chronic post-traumatic stress disorder. I continue to keep in touch with other survivors through our nonprofit charity, The American Society for the Support of Injured Survivors of Terrorism. This is my way of saluting the courage of survivors; helping others affected by terrorism gives me purpose.

Staffing the Hotline

Maria Mullei

USAID/Kenya Senior Agricultural Development Adviser and Senior Assistant Team Leader (FSN)

Navy Seabees shoring up damage to the underground parking area at the embassy in Nairobi.

Courtesy of Worley and Joyce Reed

I worked for USAID/Kenya from 1982 to 2006. I managed several agricultural programs, as well as the Women in Development portfolio, and was also an election observer for the 1987 election.

When the attack occurred, I was at home. That evening, USAID Deputy Director Lee Ann Ross called to ask if I would be willing to help set up a hotline center that concerned Kenyan families could call to ascertain the status of their loved ones—like a crisis hotline in the United States. The major difference in this case was that none of us had any idea how to run such a center, let alone how to answer the frantic questions that were coming our way. But I reported to work immediately and worked two long weeks assisting the bereaved families.

It is almost impossible to express how difficult this job was. Distraught families were calling to find out if their loved ones were alive or dead. I did not know how to answer. The only rule we were given was not to tell anyone of a death over the phone. We were told to ask each family to come to the USAID building, where we would tell them in person. Our hotline team worked under the most extraordinary circumstances.

I remember very clearly one of the difficult cases with which I dealt. A husband had dropped off his wife for work in the morning and thought nothing was amiss, even after he heard about the bombing. When he arrived home later that day and his wife was not there, he decided to check the local hospitals. When he didn’t find her in any of the hospitals, he still assumed that she was fine and that she would show up sooner or later. It did not occur to him to check the mortuary.

The following day, the husband and some of his relatives came by the USAID building to check the status of our information. I took his call and went downstairs to meet the family. It was I who broke the news that his wife had died. The husband collapsed on the spot.

I am still haunted by the sights I saw, the images on the television and the job I did. I still have not gone to the former embassy site where the names of my former colleagues are listed. I have tried to avoid anything specifically related to the bombing. Seeing the names of some of the people who were killed would bring back the memory.

Kenya had had security issues, such as crimes, carjackings and rapes—but not bombings. The entire country was shocked and did not have an emergency preparedness program prior to the bombings. Kenya has never been the same since.

On a personal level, I do not watch media coverage of bombings. I am still too traumatized to recall the events of Aug. 7, 1998. My family noticed increased levels of stress, fear and anger. I suffer from sleep deprivation at times.

Holding together as one team—Americans and Kenyans— under the excellent leadership of the most caring and skilled Ambassador Prudence Bushnell is what created a new normal for me. Working with wonderful and appreciative supervisors like Lee Ann Rose and Meg Brown normalized my life. I have maintained close relationships with them, and I feel they are a part of me, for we shared a collective trauma.

While many of the other jobs relating to the immediate aftermath of the bombing were temporary, the work of the hotline team went on for several years; and in some cases, it still goes on today. The families of the bereaved looked to us Kenyan staff who manned the hotlines for moral assistance and support well after the bombing. I consider it one of the hardest and most gutwrenching jobs any of us did. Building an organizational family culture is key for survivors and helpers.

Living with Unanswered Questions

Neal Kringel

Security Cooperation Officer in the Kenya U.S Liaison Office

My story is likely similar to those of my colleagues. Small, seemingly insignificant choices, statements and actions ultimately decided who lived and who died.

As an Air Force officer, I was assigned to the Kenya U.S. Liaison Office led by Colonel Ron Roughead. At the instant the bomb detonated—10:39 a.m.—I was in the ambassador’s office for a core Country Team meeting. The ambassador’s office was located on the top floor, one floor up and on the opposite side of the building from the KUSLO office. All those in my office were killed: Jean Dalizu, Sherry Olds and Arlene Kirk, along with Ken Hobson, who was in the adjoining office.

Normally, as the KUSLO chief, Ron would attend the 10 a.m. weekly core Country Team meeting. I distinctly remember a conversation I had with him that morning. Ron had a 10:30 meeting with the Kenyan military engineers in Thika (about a 45-minute drive north of the embassy) and was reconsidering going because he would miss Country Team. I said to him “Go to Thika; you’ve been trying to get this meeting for a while. I’ll take Country Team.” Ron agreed that I should pinch-hit.

I was still relatively junior, having only pinned on my major’s bars a week before. Normally, if Ron couldn’t go to a meeting, his deputy would fill in. However, the deputy position was gapped, with the new officer arriving in September. My fellow major, Joe Wiley, was in the United States. So, the fact that I was put in the position of attending a senior embassy meeting as a relatively junior guy was the result of multiple twists.

Survivor’s guilt, PTSD or just living with unanswered questions—all of us who remain struggle with some or all of these. —Neal Kringel

I was working at my desk that morning, and at about 9:55 Jean Dalizu tapped me on the shoulder and said, “Neal, you’d better head upstairs. The meeting starts in five minutes.” Those were the last words Jean spoke to me. Absent her reminder— would I have forgotten? Of course, I’ll never know.

I remember enduring the seemingly unending meeting, which was ultimately interrupted by several pops (the gun shots and grenades) and then by the glass-imploding detonation of the bomb. We all immediately jumped to evacuate the building, but I remember being drawn to the other side of the top floor—in retrospect, maybe by a divine hand.

There I was able to pull four victims out from under piles of rubble; three survived. I then made my way to the KUSLO office, where I found my colleagues—all deceased. Arlene Kirk, on her first day back from leave, was lying by the window. Those of us who remember the embassy know there was frequently some type of commotion at the corner of Moi and Selassie. And normally it was Arlene and I who would run to the window to see what was going on. I’m sure she heard the “pops” and went to look. But I wasn’t there to check things out with her that day.

Survivor’s guilt, PTSD or just living with unanswered questions— all of us who remain struggle with some or all of these. Why her and not me? Why them and not us? Why that day and not another? Twenty years later, I’ve stopped asking and simply accepted that I’m here and will make the most of the opportunity I’ve been given and remember and honor those who were taken from us. That’s all we can do.

Falling Windows

Patrick Mutuku Maweu

Appliance Technician (FSN)

At the time of the bombings, I was working in facilities maintenance as an appliance technician at the embassy in Nairobi, where I still work today. I reached the embassy building just about three minutes before the blast. From a distance of about 400 meters, I heard a big blast, like thunder, and saw window panes falling from buildings.

We helped rescue those trapped inside the building. My family never knew my whereabouts until the following morning. I found my family—wife, children, mum, dad, sisters and brothers— terrified and in shock. We had some counseling sessions in the embassy for the survivors.

My advice would be this: before rescuing others, make sure your life is not at risk. I arrived at the scene while the building was covered by smoke, dust and debris and, in shock and disbelief, never had a second thought that another blast could have gone off while we were engaged in rescuing.

A Long and Uncertain Road to Recovery

Carmella A. Marine

Spouse of the Deputy Chief of Mission

Embassy Nairobi was our ninth overseas posting, but our first in Africa. We were excited to go to Kenya, which we had heard was one of the most beautiful places on earth. Our two girls would be attending a good international school, and my husband, Michael, would be deputy chief of mission, his dream job. Our new home was lovely and large, surrounded by five acres of flowering trees and gorgeous flowers. The climate was ideal, and the air was crisp and clean. It seemed like paradise!

After a year, we went home on leave. Less than a week later, we were awakened by a 4 a.m. phone call from a friend who exclaimed, “Turn on the television; your embassy has been bombed!” We were stunned to see Ambassador Bushnell, wounded, walking with a colleague’s support, her hair all white with dust. The embassy building looked badly damaged, although the front facade seemed relatively intact. The details were sketchy, but Michael called the State Department and made arrangements to return to Nairobi as quickly as possible.

Initially, I decided to stay in the United States with my daughters, but after a few weeks, Ambassador Bushnell called and asked if I would come back to help with the healing process. My daughters were settled in boarding school, so I agreed, with some trepidation, to return.

The situation there was still chaotic. No one felt safe. A constant stream of visitors from Washington wanted to help, but often added to the stress. A reinforced platoon of Marines was providing security—featuring barbed wire and machine guns— for the working staff and visitors at the temporary embassy (in the USAID building). The rest of us stayed in our houses, not able to do much but worry. The final numbers of dead (213) and wounded (more than 5,000) were staggering.

Why had this happened? We later found out about a Saudi named bin Laden and a group called al-Qaida, but we didn’t understand any of this at the time. Many Kenyans blamed the Americans for the death and destruction that had rained down on their capital city. In their view, had the Americans not been in Nairobi, the bombing would not have happened.

We held a series of dinners at our house for all those who wanted to come together to share experiences and feelings. Some people were unwilling to go out at night, but nearly 100 did come. It was a way to reconnect and to cope with our fears. We all wanted to get back to normal, but now there was a new normal: just trying to get through the day. I think many people had “survivor’s guilt”—I know I did. What can you possibly say to a family that has lost a loved one? We carried on the best we could.

About a year after the bombing, on leave to see our daughters, we decided to visit a Kenyan security guard, Joash Okindo, who was still in recovery at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Washington, D.C. On the day of the bombing, Joash had been on duty in the rear of the embassy building, at the entrance to the basement parking garage. His bravery and quick thinking saved hundreds that day.

The terrorists had driven their bomb-laden truck up to the entrance gate and demanded that Joash open it. Unarmed, Joash calmly told them that he needed to “get the key.” Then, as they argued amongst themselves and pulled out weapons, he sprinted to a nearby gap between the building and a large generator shed. The terrorists set off flash-bang grenades, which sadly attracted dozens of staff to the windows, where they died when the terrorists detonated a massive explosion.

Miraculously, despite being right next to ground zero, Joash survived. He suffered two shattered legs, a concussion and numerous other injuries. Like many others, he was evacuated to Germany and then to Walter Reed, where he endured a long, painful recovery.

When we saw him, we were awed by his quiet grace. A handsome man, he stood with difficulty, proud and with a kind smile. I was so overcome that I started to cry and found myself being comforted by a person who had suffered so much. What a brave soul! Who knows how many other victims there would have been if he had agreed to open that gate?

Even a year after the bombing, Joash still had a long and uncertain road to a full recovery, but he was clearly determined. A wonderful footnote: Joash ultimately returned to Nairobi, where he accepted a new job at the embassy.

A Day Can End before It Starts

Susan Nzii

Administrative Assistant, USAID/Kenya (FSN)

I was at work in the USAID building in Parklands, waiting for my office director to clear on a Situation Report from the Disaster Assistance Response Team (working on the Burundi disaster). We heard the first blast. The second blast shook our building, and we could see papers and smoke filling the skyline in the downtown area.

There were sirens and the announcements on the PA system. We were asked to leave immediately. My brothers were happy to see me alive; we hugged and cried and called our relatives to check on them. I returned the next day to volunteer at the switchboard or the family assistance desk—the numbers and names of our fallen colleagues were flowing in. Because the morgues were full, the USAID warehouse served as an improvised a body storage facility, the bodies packed up with giant ice blocks.

I didn’t know the effect the bombing had on me until later, when I attended funerals and burial ceremonies of my colleagues. At one of these, I was nominated to read the condolence message from the ambassador—a tall order! I was the youngest in the group at this ceremony at Kangundo, in Machakos County. I greeted people in the local language and told them I was there to represent the U.S. embassy and had a letter from the ambassador. I read in English, and one of my colleagues helped me translate to the local language. Later, on my way home, I broke down and cried. I remembered the faces of the widow and the kids, who were looking at us like we would answer all their unspoken questions. It could have been me in that casket. I imagined how my family would have been affected. I cried for all my colleagues who died and for their loved ones.

I still remember the sight of the collapsed embassy and the screams and the sirens. To this day I panic during drills and when I hear ambulance sirens—I don’t like noise, and I once wet my clothes during a drill in Kabul, Afghanistan. I am more aware of my surroundings and always look for exits wherever I am.

I learned that the U.S. embassy—my employer—is committed to safety and to taking care of us; there are drills and trainings on safety, testing of the PA systems, and gas masks and all safety measures are in place. And I share this information with my family and friends: they should “duck and cover” and not run to the windows when they hear gun shots or blasts; they should keep a change of clothes and food and water in the cars and in the offices; and they should keep their travel documents and some money handy.

I have learned that a day can end before it starts. The bomb exploded at 10:30 a.m.; people were still planning for the rest of the day. They had dropped their kids at school and spouses at work; they had pending issues and unfinished business—but they didn’t have time for closure. I live each day as if it were my last.

I learned to listen more and talk less; and to be there for others, especially during trying times. I have also learned to slow down, look around and savor the moment. I can be replaced in the office, but not in my family. I spend more time with my daughter and my parents—we talk about anything and everything—death, property, education, sex, everything!

Every day is a new opportunity.

A makeshift memorial was erected on the grounds of the former U.S. embassy in Nairobi in the days following the August 7 blasts. The text reads: “Together we mourn and sympathise with our fellow humans.”

Courtesy of Worley and Joyce Reed

Carry Lessons Forward

Gregory Gottlieb

USAID/Kenya Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance

When the attack occurred, I was with my wife and two kids in Portland, Oregon, ready to return to Nairobi. We were at Andrews Air Force base three days after the bombings, when the bodies were returned and President Bill Clinton spoke. We left that evening, Aug. 10, for Nairobi.

My job was to work with my Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance colleagues on response efforts, and for the next eight months I was the head of the recovery unit.

I struggled with the question of why men would kill kids, street vendors and bank clerks to try to get at a few Americans. There is no answer to the question, but asking it over and over left me with a nagging sense of insecurity.

Among my family members, our son took it the hardest—the parent of a friend was among the dead. He developed depression, and three years after the bombing, we left Nairobi at the urging of the State Department psychologist. Our son still suffers from depression.

Most colleagues not in Nairobi quickly moved on from what happened. In one sense, that was all they could do. I grew closer to colleagues who stayed in Nairobi, as they were the ones who could best understand the impact that such an event has on individuals and communities.

I took time to think through the “whys” of such an attack. Later, as I went to work in other critical-threat posts, I lived my life with greater understanding of the threats and impacts of terror. I became an advocate within USAID for preparing to deal with staff issues attendant to terror attacks and living under constant security threats. Some did not want to hear my thoughts, but advocating for future victims made me feel as though I was ensuring that my Nairobi colleagues who were killed or injured were not forgotten.

It is important to stay connected to those who went through such an event with you because of a shared understanding, which makes it easier to talk about what happened. I still carry inside me considerable anger at the State Department for their dismissive and slow response to mental health issues, but talking about that tension helps lessen it.

My advice to others is to not hide from the impact of an event. It is important to see a counselor. Listen carefully to your kids and spouse to assess the impact of the event on them, and then figure out what changes in yourself or your circumstances are important. If you remain in the Foreign Service, particularly if you advance to a senior leadership position, you must carry forward the lessons concerning staff care.

Processing, Helping and Healing

Joanne Grady Huskey

FS Family Member

When the bomb went off, I was in the basement of the embassy at the doctor’s office with my two children, Caroline (5) and Christopher (8), waiting to undergo their school physicals. I had unwittingly parked my car immediately next to the truck in the parking lot, where the two men who set off the bomb had watched us walk into the building. My husband, Jim, was on the fourth floor in a meeting in the ambassador’s office.

One minute after we arrived in the doctor’s office, there was a deafening blast that blew us all to the ground. As I regained consciousness from the sudden tremendous jolt, I found myself on the floor, dazed and confused. I realized that my children were somewhere in that dark room in the rubble on the floor. They called out for me and asked, “Is this an atomic bomb?” “No,” I said, “but it is a bomb, and we are going to get out of here.”

I searched for them in the dark and gathered them to me. Clinging to each other, we crawled on the floor over cut glass and debris, groping in the dark through wires hanging from the ceiling, climbing over furniture completely in disarray as we searched for a way out.

Following the mental map I had of the hall layout, I pulled my children along the dark corridors. Still alone, we finally saw a light at the end of the long hallway. We followed the light and climbed through a hole in the wall. Entering the pitch-black garage, we ran up the ramp leading out the rear of the embassy and hit a 100-foot wall of fire, precisely where I had parked our car!

The buildings behind us had collapsed. It was chaos. I saw one Kenyan man covered in blood, without clothes, and others running around with utter fear in their eyes. We ran around the perimeter of the embassy, and my kids slipped through the iron gate into the arms of their shocked and panicked father, who had frantically run out of the building, sliding down four flights of stairs, scared to death that we were all hurt or worse.

FSO Kevin Richardson and my husband pulled apart the iron posts of the barrier with their bare hands, letting me out of the perimeter. Colleagues in front of the embassy exchanged rumors that all the U.S. embassies in Africa had been blown up. We weren’t sure if the perpetrators were still there or not.

Gathering our family together, we ran away from the burning embassy as throngs of Kenyans ran toward it. My husband spotted a car with embassy plates across the median. We jumped over, and he threw us into the van, telling the driver to get us home. Saying goodbye to their father, our children cried for the first time when he went back to the embassy to help victims get out. We zoomed through the chaotic streets of Nairobi, driving on the sidewalk until we could go no further. We jumped out of the car and ran the rest of the way home, covered in white soot, our faces blackened by bomb debris. People stared, shocked to see us.

After the bombing, we pulled together as a family and became even closer than we already were. The preciousness of our lives was ever present in our minds.

Although offered the option of leaving Nairobi, we opted to stay and help Kenyan victims. As president of the American Women’s Association, I got involved in organizing a relief fund for Kenyans injured in the attack. I met Kenyans who had been blinded, deafened or paralyzed by the bomb. This had a profound effect on me; working with them helped me to heal my own wounds. We were able to fund the rehabilitation of many victims.

This event changed me forever, in that I became an active advocate for citizen diplomacy. The perpetrators of the bomb hated Americans without knowing anything about us; and we, in turn, knew close to nothing about them or why they would do this to us. From that moment on, my life’s purpose has been to promote understanding between people of differing backgrounds.

It helps to stay close to those who understand or even know firsthand what you’ve been through. Don’t stay away from someone who has suffered a trauma. Be there for them, even if you don’t know what to say or do. Your presence alone helps so much.

Being able to actively respond to the trauma was healing for me. Telling my story, setting up a relief fund and refocusing my career all helped me feel less victimized, and gave me a way to make sense of the bombing and of terrorism in general. It is important to find your own way to process trauma and give yourself hope for the future.

Hold Together as a United Family

Lucy Mogeni

USAID/Kenya Administrative Assistant (FSN)

On Aug. 7, 1998, I was in Parklands, the USAID offices, on duty. I was working for the USAID Population and Health Office as I had done for 10 years. This was a Friday and, as usual, a short day. Schools were closing for their August holidays, so I was very excited to go home early to be with my children.

At about 10:30 a.m. I saw a lot of smoke and flying objects moving skyward. The black smoke increased over time, and I became curious, wanting to know where it was coming from. The first person who came to mind was my dear friend, colleague and sister, the late Cecilia Agnes Mamboleo, who was working in the Human Resources Office. To my surprise, the phone could not go through as usual, so I dialed the number at the switchboard and asked for extension 248.

To date, I have never forgotten these three digits. I had spoken to Cecilia many times each day. She had informed me the previous day that she was busy working on her handover notes, because her children were finishing school, and she would take two weeks to be with them. I came to learn that Cecilia died on the spot at the time of the bombing.

Immediately after the bombing, we were called to provide help in identifying the bodies of our colleagues who were in different morgues. I found my dear friend at Lee Funeral Home. Oohhh, no! When they began opening the drawers, I was still in denial and believed that my friend was still alive; but as they went on opening the drawers, I saw her feet and that she was wearing her favorite African trouser outfit.

That’s when it sank in that she was actually gone for good. We had been neighbors, and our children went to the same school (Consolata School), so her family members were waiting eagerly in my house to hear the good news that we had found Cecilia in one of the hospitals, alive and being treated.

The date, Aug. 7, 1998, is still fresh in my mind 20 years on. I never knew how vulnerable I could be until after the bombing. My family members, who were young then, witnessed our close family friend, Cecilia Agnes Mamboleo, die; and they saw how it affected her family. It took me 15 years to go back to the bomb site at Haile Selassie Avenue. It is a place I pass by daily; yet I still never want to accept that the U.S. embassy is no more.

I realize I lived in denial for a long time, but eventually I allowed myself to find some healing by taking a walk at the site. I meditated and read the names of the colleagues who had worked in the embassy. I visited the museum and watched the bombing video, which unlocked memories that will live with me forever. I keep praying, and anytime I remember the departed souls, Cecilia’s name pops up first. Rest in peace, my dearest sister; life will never be the same again. I pray for Elvis, Sally, Teddy and Kevin, that they hold as one family and know that their mum’s spirit is still in their hearts.

Talking about it from time to time with my colleagues who survived has helped me bounce back, and this has become therapeutic. I appreciate the drills that are being conducted at my workplace, and I take them seriously.

My advice is that we hold together as one united family, and pray for each other and for God’s strength. We have tried to form a support group for the survivors because, though it has been 20 years, it’s still fresh in our minds.

Handprints on the Wall

John Dunlop

Regional Nutrition and Food Security Adviser, USAID

During a whirlwind visit to Africa then-Secretary of State Madeline Albright visited the destroyed U.S. embassies in Tanzania and Kenya. Here, on Aug. 18, 1998, she lays flowers at the entrance to Embassy Nairobi.

Courtesy of Worley and Joyce Reed

I was in the Regional Economic Development Services Office Towers in Parklands when the bomb exploded less than two miles away. The shock wave hit our building, and for a moment we thought an earthquake had hit. As we went to the windows, a mushroom cloud appeared over downtown Nairobi.

We watched for a few minutes, and then a call came over the loudspeaker for anyone with medical experience to report downstairs. Just as that call came, many bits of burning and charred paper started floating out of the sky around the building.

Being a former paramedic with search and rescue experience, I headed downstairs. Four or five of us piled into a car and headed downtown. The streets were already closed by police, but we managed to get through and made it to the embassy. It looked relatively intact from the road, but a big horizontal crack running along the foundation, perhaps a foot or two above the ground, spoke to the idea that perhaps the entire building had been lifted off the ground. All of the windows on the back side were blown out.

The building next door, which had once been a sewing school, had been reduced to a pile of bricks. The bank on the opposite side of the parking lot seemed like it had acted as a chimney, directing the blast upward. While it was still standing, many of the windows had been blown out.

We went to the front of the building where people were congregating, getting into cars and vans to go to the hospital. I found one of the regional security officers, introduced myself, and we began to put together the first of two search-and-rescue teams. As we entered the building, it was clear that Post One had been devastated. Broken glass and rubble was everywhere.

We headed toward the back of the ground floor to find that the walls had been ripped away, and the entire back was open to the parking lot. A Marine stood watching as Red Cross volunteers entered the building. We moved them out again fairly quickly, as this was still the embassy and theoretically a controlled space. Controlling the chaos seemed like a good first step.

As we moved upstairs to look for survivors, it was clear what had happened: the blast had brought down the interior walls on the side nearest to the parking lot and had blown in all the windows. Much of the floor was covered with cinder block-sized chunks of concrete, perhaps two feet in depth—deep enough to hide bodies.

As we got to the ambassador’s suite, I remember the destruction not being quite as bad, but debris still lined the hallways. A vivid memory for me is a series of maybe 10 bloody handprints on the wall in the hallway leading to the stairs. Someone had walked down the hallway, steadying themselves against the wall and leaving those handprints as they escaped the building.

We cleared the floors room by room, but below the top floor, the job got slower and tougher. Looking for survivors, to my recollection, we found only one person who was still alive and hadn’t already gotten out.

The hard work then began as we sought to shift rubble looking for people who might be trapped or hidden. Think of the child’s game made up of a set of squares that you slide around trying to make a picture. We would clear one area, maybe 4 feet by 4 feet. Next, we moved the rubble in the next 4 x 4 square into the empty one, and so on and so on, methodically clearing room after room. It was backbreaking work. Each chunk of concrete weighed about 40 pounds and we found very few bodies. This went on for two days until the Israelis eventually showed up with dogs that took over for us.

We tried to help with the sewing school, too. But it was difficult. The building was so devastated that there was little we could do.

I went home after that and slept for a couple of days.

The Sheer Extent of the Horror

Charlie Slater

Senior Financial Management Officer

Finished with a few unexpected meetings in Paris, I was in my hotel room packing to return to London to collect my son, Forbes, at his grandmother’s house and fly on to my new assignment in Nairobi. A Parisian friend called: “Quick, turn on the television. But first—they said no American was killed in Dar es Salaam.” My wife Lizzie was in Dar. Huh?

Embassy blown up in Nairobi. Embassy blown up in Tanzania. What?! Catch the train? I was by then so late there wasn’t anything to do but run to catch the train. As I exited at Waterloo, I saw a picture of my good friend and soon-to-be boss, Steve Nolan, already on the cover of a London tabloid…he had blood on his clothes but was alive.

I decided to leave my son with my mum and rushed to catch my Nairobi flight.

I arrived in Nairobi early Saturday morning not really knowing what had happened in Dar or Nairobi, except that it was bad, and my wife was—probably—alive. The usual embassy driver and expediter weren’t there to meet me, so I took a taxi. I can’t remember why, but I went to the USAID building. I clearly remember walking with my suitcase into the second floor, where I was met by a whiteboard on an easel. The whiteboard was filled with rows of names: On the left were the “missing,” with names crossed out apparently as they reported in. On the right was a list of the deceased. There were seven friends of mine on the wrong side of the list. My deputy’s name was there, the young mother of three small kids. I can’t conjure up a word for my reaction.

That day was a blur. I learned that of my 18 staff, half were either dead or seriously injured. When Steve saw me at about 10 p.m. and asked where I was staying, I realized I had no idea. He took me home with him; I stayed for about three weeks.

I couldn’t call Dar, and Dar couldn’t call Nairobi. Calls could get through to the United States, so a friend relayed messages between Lizzie and me. Over the coming weeks, what started as “a few scratches” on my wife’s face turned into a few cuts turned into some wounds turned into a loss of her nose and her eyesight—and gangrene. They finally convinced my wife—she of unimaginable stubbornness and dedication to her friends and country—to be medevaced to Nairobi.

Over the course of the next few weeks and months, we all worked seven-day weeks, about 18 hours a day. All my hair turned gray; my weight dropped to 122 pounds. A few days after the bombing, I took my deceased deputy’s husband, mother and three small children to the airport to fly home to the United States. We were in the departure lounge when her youngest, a 3-year-old cutie, looked up at me and asked, “Where is Mummy? Isn’t she coming with us?”

A woman I didn’t know came to my office one day—picture an 18 feet by 18 feet room shared by 12 accountants and a group of Marines—and asked to pay her phone bill. I explained that the cashier had been killed and all our records were gone, but I could see that something was seriously wrong here: the woman was bent on paying her bill. I flipped through some papers and made up a number, and she wrote me out a check. I later learned that she had lost her husband and son in the bombing, and was insisting on taking care of the usual details of departing post.

I was called to report to the ambassador’s residence—the families of the deceased Kenyan staff members wanted information on their finances. As I entered the back garden I saw more than 200 Kenyans waiting for me to explain what they would do now that their sole breadwinner was gone. It wasn’t just 37 Kenyans who had died that day; it was hundreds of Kenyans, and Americans, whose lives had died that morning. That was the day that crushed me the most, the sheer extent of the horror sitting in front of those people, who were all waiting to hear “What’s next for us?”

Fast forward to 2012, when I was once again serving in Nairobi. I was chargé d’affaires when I was called to the embassy late one night. We had pictures of a foreigner who had been killed in Somalia, and he looked just like Fazul Mohamed, al-Qaida’s reported mastermind behind both bombings. Fourteen years of searching, with a $5 million reward, finally paid off. For my small part, I sent two FBI agents to the Mogadishu airport early the next morning, and they confirmed through fingerprints that this bastard was dead. I felt a circle had been closed.

Tears Taste the Same Everywhere

Brian W. Flynn

U.S. Public Health Service

The remains of the Foreign Commercial Service office, and an adjoining restroom, in U.S. Embassy Nairobi after the blast.

Courtesy of August Maffry

When the attack occurred, I was on active duty as a commissioned officer in the U.S. Public Health Service where, among other roles, I directed the government’s domestic disaster mental health program. USAID asked me to come to Kenya (passing on a request from the Kenyan Medical Association) to advise on the psychosocial impact of the bombing on Kenyans. In Nairobi, I was based in the combined USAID/State Department building, and soon became engaged in observing and consulting on the psychosocial impact on members of both of those organizations, as well as the Kenyan response.

I worked closely with all levels of both organizations, including the medical leadership and Ambassador Bushnell and her staff. Later, I worked with USAID to review and administer a mental health program for Kenyans. I also worked with other U.S. mental health colleagues to assess the mental health impact of the bombings in both Kenya and Tanzania.

Working on the other side of the world with Americans, as well as people of different local cultures, was a new experience for me. I felt an urgency to make an impact quickly and to try to determine what of my knowledge and experience applied here. Candidly, I was not as confident in my abilities as usual.

I was also struck by witnessing the very personal impact on U.S. personnel who needed to lead in the midst of personal loss, as well as organizational and political upheaval.

While I was in Nairobi, my home in Maryland was robbed. I learned through a late-night call from my wife; she and our young daughter were terrified. I learned what many USAID and State Department folks know all too well—sometimes professional responsibilities must trump even powerful family needs.

I learned a great deal from my Kenya and Tanzania experience; and that, along with the experiences of those I encountered in Kenya, continues to inform my teaching, consulting, mentoring and writing. Our combined experience has helped to better prepare a new generation of disaster and emergency mental health personnel.

I would like to pass on the following advice for those who may become survivors and helpers in the future. As a helper, be as prepared as you can be, but know you can never be as prepared as you want to be. Know and respect the organizational culture in which you work and the culture of those you serve. Understand that tears taste the same no matter the color of the cheeks over which they roll.

You Will Survive

Justus Muema Wambua

Warehouse Team (FSN)

I arrived at the scene 30 minutes after the blast. It was terrible. There was no light. You could not see anything in the building. We were instructed to use flashlights, which we brought from the warehouse. When we got inside the building, it was so sad for me because I went to the location where my friends were, in the shipping department. I found all of them dead. I was shocked. The first was Geoffrey Kalio, then Joseph Kiongo, Dominic Kithuva and others.

When I saw that, my mind was confused, even my pressure went up; but God is good. I tried to put myself into another frame of mind because there was nothing else to do, and I gained strength and started to move the bodies from the building to the mortuary.

I have three children who were in school at that time, and they were affected very much because they saw me every evening after work. And I was working 24 hours at the embassy to make sure all the bodies were out of the building and sent to a designated place to await a burial date.

My children were worried. “What is happening to Daddy?” they cried. They constantly asked their mother where I was. She had a difficult time.

What makes me who I am is praying to God. Today, when I hear a sound like a blast, I just feel scared because of that experience.

I would like to tell friends that when a blast comes and you are not dead, take comfort in that, and you will survive the situation.

A Scene from Hell

August “Gus” Maffry

Commercial Counselor

August Maffry stands at the memorial to the victims, erected at the site of the former U.S. embassy in Nairobi.

Courtesy of August Maffry

9:55 a.m. My deputy, Riz Khaliq, and I met the ambassador in the embassy underground garage and headed for the Cooperative Bank Building next door—about a 90-second walk—for a meeting with the Kenyan trade minister. The ambassador’s driver escorted us. We joked that he should carry the flag, usually mounted on the limo’s front fender, high in his hand, because he and the ambassador were on foot for a change.

10:05 a.m. In the minister’s 20th-floor office, we talked for 20 minutes or so about bilateral relations and plans for the upcoming visit of Commerce Secretary William Daley.

10:35 a.m. A very loud boom stopped the meeting and brought everyone to their feet, puzzled. My first thought was terrorism, as I had heard bombs go off near the embassy in Rome 10 years earlier. Against my better instincts and training, I approached the office window to within a few feet to have a look and asked, “Is there some construction going on?”

“Well, you never know what’s going on in the railyards [across the street],” the minister observed. Ten seconds had passed since the first boom.

The next moments defy description—no words are adequate.

First, the plate glass window was silently caving toward us, imploding and coming apart in slow motion. I saw the glass separating into shards (or thought I did). I felt a terrific wind, but no sound. I remember an astonishing sense of disbelief as the whole office disintegrated in an instant amid the comic book CRRAAACCK of a massive explosion.

Dust and smoke were everywhere. Imagine an earthquake, tornado and hurricane hitting at the same time. It felt like the end of the world, a sense so many articulated that day. I lost consciousness for a few seconds, perhaps half a minute. Having been thrown across the room, I was disoriented in time and space and struggled to understand what was happening. I was facedown, unable to see anything or breathe right, and covered in dust and debris, as the whole ceiling had come down in pieces. I wondered whether I was dying or already dead.

The terror transcended fear in the usual sense—I guess that’s why they call it terror. No pain, just disbelief and acceptance. The force of the explosion was so great that I was certain no one in our vicinity had survived.

As the shock wave and sound passed, I realized I was conscious and probably alive. I got to my knees and checked that my limbs were still there. I suspected head and chest wounds but didn’t know how bad they might be. The blood and dust were blinding me; I could see only broken furniture and pieces of the ceiling.

I couldn’t see or hear much of anything, including my colleagues, but I could see the office was evacuating into a stairwell. As we descended, it was a scene from hell. I gradually realized that the whole skyscraper had been blown up, not just the minister’s office. At each landing, the doors, walls and partitions were gone. I could see daylight in all directions, all the way out through the windows on each floor, where offices now in ruins had stood. It had still not sunk in that the bank may not have been the primary target, but was merely a collateral target.

I was being swept on in a tide of humanity trying to escape the building, down the stairwell to the exit some 40 flights below.

People screamed, moaned and prayed. One woman kept repeating, “Dear Lord, if you get me out of this I swear I will never sin again.” It was raining blood; the banister was slick to the touch. I stepped over three dead or dying bodies. There was no stopping, though, just a mass of people pressing on and down, not knowing whether there would be another explosion, a building collapse—not knowing whether they would survive. The real danger, it turned out, wasn’t another bomb but panic. I kept pleading with people that if they wanted to get out of there, they’d have to remain calm and not push. There was no panic.

My office sustained 70 percent casualties: two killed and two blinded. Both surviving victims have successfully rebuilt their lives. I was determined to put our office back together and succeeded, thanks to the dedicated efforts of my remarkable U.S. and Kenyan staff. I was also inspired by Ambassador Bushnell’s leadership. After the bombing, some of us went off on medevac to the hospital. The ambassador herself, with glass cuts, shaken and bloodstained, was back at work the same day. I also remember Riz Khaliq’s presence of mind in escorting Ambassador Bushnell out of the bank building.

This is what helped as I created a new normal for my life: The South African Air Force medevac team and the medical staff at Mil One in Pretoria got me through the early days. As for later PTSD problems, my hat is off to the civilian psychologists, some at the State Department’s Bureau of Medical Services, but mainly at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center. Those military guys sure understand explosions.

I appreciate the fact and quality of life like never before. I no longer worry about something like having to get up early. It’s a thrill being able to do that, because I can. I don’t worry much about the small stuff.

Given what I learned that day, I would like to pass on the following advice for those who may become survivors or helpers in the future.

• Don’t dwell on survivor’s guilt. That was fate at work.

• Being present at a terrorist attack might seem like bad luck. If you survived more or less intact, however, you weren’t unlucky: you were lucky. Those who perished or were severely injured, and their families, are the ones who need our support and deserve our homage.

• Think about what is really needed in an emergency. On Aug. 7 at the Nairobi Hospital emergency room, where there were 2,000 admissions in one hour, it was sandwiches for the overworked staff that were needed, more than doctors, nurses and medicines.

•Be sure to send some staff home to rest right away, so everyone doesn’t get tired at the same time.

•A word to the wise: Stay away from windows.

Bombings Were Not on Our Radar

Lee Ann Ross

Deputy Director, USAID/Kenya

The memorial erected on the grounds of the old U.S. embassy in 2001.

Zweifel / Creative Commons

State and USAID were in separate buildings about three miles apart. The eight-story USAID building became the offsite command center after the bombing, and USAID FSNs played an important role. The embassy moved in with us until they were able to set up a temporary building. We took an already crowded building and turned it into a ridiculously crowded building, yet somehow it all worked.

When the attack occurred, I was photocopying at the USAID building, and I thought a container had fallen off a lorry. Having grown up in Laos during the Vietnam War, I instinctively moved away from the windows. When I saw the smoke rising from near the embassy, I thought the Kenya Teachers Union offices had been bombed, as they were on strike and at odds with the government.

Chaos ensued. When the ambassador arrived and asked for a volunteer to manage the offsite recovery effort, I volunteered. I was the USAID deputy director at the time, and it was my second posting to Kenya, so I knew my way around town, and I knew my staff well. The fact that a USAID officer was designated to be in charge spoke to Ambassador Bushnell’s successful effort to build a true Country Team. All of us got along well. We were an embassy family, not a collection of acronyms. I doubt there was an embassy in the world that was better positioned than we were to get through this.

We got blown up. We were a high crime threat post, but a low terrorism threat post. Crime was stressful but expected. Bombings were not on our radar. No one expected this.

In 1998, there was no 911 in Nairobi. No FBI, no Federal Emergency Management Agency, no first responders, virtually no ambulances. We were on our own. At the USAID building, we started trying to figure out who was alive and who was dead. We tried to use the phone list, but that was out of date. We used the radio list for U.S. personnel, and we called the regional accounting office in Paris for the Foreign Service National payroll list.

Our Kenyan staff worked the phones, taking calls from families wanting to know if their loved ones were alive or dead. If they were dead, we asked the families to come to the office, as we didn’t want to give out death notices over the phone. At one point someone from Washington asked if we trained folks to do this. Are you kidding?

I called all the counselors I knew in town and asked them to come down. I told them I didn’t know exactly what we needed, but I knew we would need their presence. Someone ordered body bags.

There is nothing normal about surviving a bombing that takes more than 200 lives, but staying together and being with folks who shared the experience helped normalize it. I can’t imagine rotating to a new post where no one could begin to understand what happened. We became our own family, and we created our own normal.

On the USAID side, we received $34 million from Congress to help bomb victims, which meant we continued to do bomb work every day for years after the bombing. This event did not go away.

Advice for those who may become survivors and helpers in the future:

• Get to know your peers, and become friends with your colleagues in other agencies. Break down the institutional barriers. Get to know and respect your FSN colleagues. They are smart, and you never know when they may save your butt.

• Each person will react in his or her own way. Don’t hold their reactions against them. They did the best they could do at the time.

• The disaster tourists will come and go. They won’t be very helpful. Nothing in D.C. will change because of their visits. You are not obligated to reinjure your psyche by taking them on tours of the blown-out building so you can tell them whose blood is on the wall. Take care of yourself first.

• If your embassy gets blown up, accept that all of you are on your own. If you think Washington gets it, you are kidding yourself. Washington is interested in placing blame, not in helping you. You’ve been told your whole career that you are among the best and brightest. For State MED, this translates into “You don’t need help.”

If you get PTSD, they’ll say, too bad for you; it means you are weak. But this response denies you your humanity. Guess what? You probably will get PTSD if you go through something like this. You will be on your own to get help. Do so.

• Remember: you are human. PTSD is a physiological reaction to trauma. It is normal. It is not a sign of weakness or a character flaw. What is not normal is for the State Department to deny services to its employees who, almost by definition, go around the world collecting traumatic events over a career. It is unconscionable. If you have cancer, MED will refer you to a specialist. Will they do the same if you come in with PTSD? No. Can you get worker’s compensation for this? Yes, you can. Document your trauma, and apply for it.

Will you be considered damaged goods by the system? Probably. Will you be damaged goods if you don’t get help? Surely. If you don’t do it for yourself, do it for your family. To this day, my daughter tells me that she lost her mother due to the bombing. Don’t let that happen to you.

Coincidences in Life

Stanley K. Macharia

Senior Security Investigator (FSN)

It has actually been 20 years since the bombing incident and 10 years since I retired from Embassy Nairobi. Time passes; and yet all this is like yesterday. But looking at my own children, and now grandchildren, I realize that many years have passed, and I am without doubt getting old. At the age of 70, I must thank God that He has brought me this far and, most importantly, thank Him for giving me an opportunity to serve the U.S. government at the embassy in Nairobi.

In life, there are many coincidences. We draw many lessons from such occurrences. One of them so cardinal to my life is that in about 1994 the U.S. embassy (through a certain assistant regional security officer whose name I can’t remember) approached me to help secure the perimeter of the embassy. They had tried to approach Nairobi city authorities with no success. I made it my duty as the assistant commissioner of police in charge of police operations in the city, and had it done.

It was those metal barriers surrounding the embassy that saved me four years later. It is common knowledge that had the bad guys succeeded in driving the bomb carrier into the embassy basement, I would have died, together with all those who were inside at the time. The explosion would likely have uprooted the entire embassy and affected the entire Nairobi central business district and the environs, with terrible results. That means thousands more lives would have been lost, along with an unimaginable amount of damage to property.

Much of my story was covered in detail in an earlier statement, but I can’t forget to mention the second coincidence, the one that actually saved me.

This is what happened that day of the bombing. At about 10 a.m., I heard some explosions outside and decided to go and check. I headed to the rear of the building through the stairs leading to the basement. Halfway, as I was about to open the metal door to the motor pool office, something strange happened; I suddenly felt nervous, terrified, like one walking through a dark path, and all at once my instinct told me that all was not well.

Our Kenyan staff worked the phones, taking calls from families wanting to know if their loved ones were alive or dead. —Lee Ann Ross

I eventually and unconsciously made an about-face and started running toward the main embassy entrance. Before I exited the stairs, the bomb exploded. It was such a strong explosion that I lost control and fell to the ground. After a few seconds I gained consciousness and ran out; but before exiting, I met a lady I knew coming out of the Visa Section, and I helped her out. She was bleeding from some injuries. Luckily, I was not injured but was dusty. Later, I helped rescue the ambassador from the area and joined the security rescue teams that came to help.

As a result of this incident, the government of Kenya put in measures to combat this menace, and the security agencies are more alert than before. As a person, I learned to trust my instinct in every situation, as I continue trusting God in everything that I do.

Last but not least, I wish to mention that in January 2005, I attended the Senior FSNI Seminar in Washington, D.C. One of the lecturers discussing the 1998 Nairobi bombing insinuated that some local embassy employees knew about the bombing. This annoyed me, and I protested, because as far as I can remember, there was no such information.

I end with a positive note of appreciation. After 20 years the victims of the embassy bombing have been remembered and granted compensation that extended to their entire family and made a huge impact. We are now able to complete lifetime projects that will support our families for many years to come, and I take this opportunity to sincerely thank the United States government for this consideration. It has come at the right time for those who are living and the families of those who perished in the incident.

May Almighty God bless the government of the United States of America and all those who coordinated this matter [of assistance] from the beginning to the end.

Listening for Familiar Voices on the Radio

Teresa Peterson

Co-Community Liaison Officer

I had planned to go grocery shopping with Sally, the wife of the assistant regional security officer, leaving my children with hers for a playdate. I also planned to stop by the embassy to cash a check, but at the last minute I changed my mind, feeling I had funds to purchase a few necessary items until the following week.

Sally’s driver Steven took us to Village Market to shop and enjoy a girls’ day out. The excitement of being in a new culture was intoxicating— my family had arrived in Nairobi only two weeks prior.

As we strolled the outdoor venue, Steven came running to me with a handheld radio and said anxiously, “Ma’am, something bad has happened—you should hear this.” We quickly learned of the embassy bombing as everyone was asked to stay off the channel, now the main line of communication. As we listened we learned two things—the magnitude of the damage, and that Sally’s son was on the radio trying to find his dad. At that moment we realized the children were already aware of the event. We needed to get back to her house as quickly as possible, but the main roads were being shut down. Fortunately, Steven knew a back way.

We continued to monitor the radio in search of familiar voices. We knew that Sally’s husband would be working closely with my husband, the regional security officer [Paul Peterson]. Neither voice was detected during the hourlong ride back to her house, and anxiety was beginning to build. When we finally arrived back at the compound, our children were playing, the sky was blue and it was a beautiful day. At first glance, everything seemed right with the world.

Spouses gathered in the living room of one home, and everyone placed their radios in the center of the coffee table, continuing to listen for familiar voices. The TV was tuned to CNN, which was broadcasting the aftermath of the horrific event. Hours went by, and some were relieved to hear their loved ones’ voices, while others remained numb.

I decided to return home with my children and try to remain calm, keeping things as normal as possible until I learned one way or another the fate of my husband. I was angry because he had not reached out to let me know if he was safe, but I reminded myself that he was working. This is what he was trained to do, and he works best under pressure. Stopping to call me would have been a selfish act, especially given the number of casualties.

The bombing occurred at 10:30 a.m. It was after midnight before I knew my husband was alive. When I opened the door for him, I discovered a man I barely knew. He was covered in black soot from head to toe. We clung to one another for what seemed like hours. As he showered and changed into clean clothes, I made sandwiches and coffee for him to carry back to the site as he returned to work. With our children safely tucked in their beds, all I could do was cry and pray for his safe return after the loss of so many.

I later learned that everyone in the line to cash a check that morning had died. Why I changed my mind at the last minute I will never know.

Over the next week, I volunteered to sort and categorize personal items found at the blast site. Shortly after, I accepted a position as the co-community liaison officer. I felt strongly that it was within my ability to contribute to the rebirth of the embassy and community morale.

My advice for such a time is to keep the event alive by remembering and honoring those who were lost, the victims as well as the survivors. Everyone has a story. Be compassionate. Listen and offer assistance and a shoulder to cry on. Be a friend.

The “Ripple Effect” of Trauma

Sam Thielman

FS Regional Medical Officer/Psychiatrist

I was deeply involved in the private practice of psychiatry in Asheville, North Carolina, on Aug. 7, 1998. I remember hearing the news stories about the bombing on television; but frankly, I did not pay much attention to them. To me, at that moment, the East Africa bombings were just another world tragedy reported on ABC nightly news. The impact on me only began four or five months later when, during my interview for a job with the State Department as a regional medical officer/psychiatrist, I wondered why so many of the questions had to do with how I would handle the psychological aftermath of an embassy bombing.

In disaster psychiatry, there is a lot of discussion of the “ripple effect” of a traumatic event, and my family and I were certainly affected by this rippling. My first trip to Nairobi in my new capacity as RMO/P was in the latter part of 1999, some 16 months after the bombing. When I arrived, I was not only new to Nairobi, but to Africa, to overseas living and to the culture of the Department of State.

I quickly learned that I was only one of many new people in such a position. In my role as the embassy mental health provider, I soon became aware that my work was exposing my wife and children to a community that was bereaved and angry. There were many who were cynical about the disaster response and about Washington’s efforts to help. We were in an environment that seemed continuously dangerous. My family resented me at times for having taken them from the beauty and safety of the mountains of North Carolina to this situation of comparative deprivation and threat.

I also became aware of the power of vicarious traumatization— the phenomenon in which people who hear stories of disaster over and over are themselves psychologically affected by the disaster. Many were skeptical about claims of psychological distress by those at the mission who, though in Nairobi during the bombing, were not at the embassy itself when the bomb exploded. But exposure to the dead bodies of friends, stories of death and destruction and pressure from all quarters to keep going took a serious toll on everybody. Vicarious traumatization was known to the disaster response communities in 1999, but was not yet recognized as a cause of PTSD by the American Psychiatric Association. This led to a lot of unnecessary instances of “blaming the victim.”

The embassy community at the time of our arrival was comprised of a mixture of survivors and of those who had come to help rebuild. Both groups were hurting. I was struck by the fact that some of those who were hurting the most were the people affected by the pain of their colleagues.

For all of us, the sense of community was especially important, a powerful force for healing. The new ambassador, Johnnie Carson, was a decisive and empathetic leader. This was his fourth ambassadorship, and he had seen the impact of the Rwandan genocide on the embassy community when he was ambassador to Uganda. He had a forward-looking focus and made clear the need to continue with the work that the U.S. government had been doing in Kenya before the bombing.