When the Going Gets Tough: Moscow

Reflections

BY ANNE GODFREY

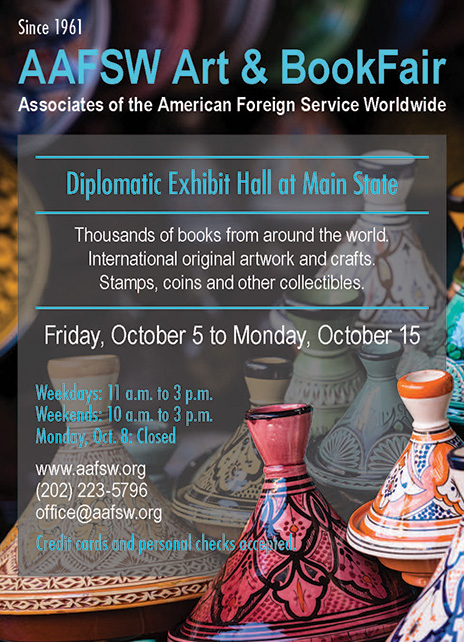

Deputy Chief of Mission Anthony Godfrey stands alone on the tarmac, watching the plane pull away with 60 diplomats, their families and dozens of pets aboard.

Charles Starr

Children of expelled diplomats wave an American flag during their flight out of Russia.

Thomas Bruns

Things have gotten tough in Moscow—again. In early April, we had the second mass expulsion of American diplomats from Russia in eight months. I could write a book about the resilience and sheer bloody-mindedness of those of us leading this Foreign Service life.

It’s difficult to describe the shock we felt as the names rolled in one at a time. Neighbors, friends, senior diplomats, bright young officers, families—whole sections of the embassy, all given seven days to pack up and leave. I sat in a neighbor’s house wearing, I’m sure, the same expression of dazed disbelief as everyone around me at the implications for us as a community.

Many outside the community asked me how we got through this for a second time in less than a year. Sixty percent of our embassy and consulate employees were kicked out in August 2017. How would we manage to keep going again, after the loss of so many more? There is no easy answer to these questions, but one thing I can say for sure—the extraordinary community we have here, both professional and personal, is one I have not experienced anywhere else in 20 years of Foreign Service life.

A Bureaucratic Miracle

In the week that followed the announcement of names on the list, as the community considered the enormity of the loss—60 of the finest officers and their families—we faced a staggering task. To get everyone packed out on time, the community had to perform a bureaucratic miracle. Departing diplomats continued to do their jobs while they completed a to-do list, one that is usually spread over months, in just one week.

That list included never-ending checkout requirements. We set up seven desks in the community room, staffed by every available officer and volunteer. Paperwork was completed by four or five different departments, keys and radios turned in, packouts scheduled, seats on the charter flight confirmed.

The list included checklists for exporting pets: certificates of health, up-to-date rabies shots and airline-cleared pet carriers for 39 pets.

The list included explaining the situation to the children—some with just 11 weeks left in the school year, including high school juniors immersed in their first year of the International Baccalaureate diploma. None could be given a satisfactory answer to the question of how they will complete the year, or where they will be next school year.

Those of us who would be staying behind cooked for friends and arranged play dates to get little ones out from under the chaos. We walked dogs. We sent our teenagers to carry bags and boxes. We made things up as we went along, dealing as best we could with a situation for which none of us had a frame of reference.

On the morning of departure, the compound stirred earlier than usual. At 4 a.m., suitcases were stacked outside. Pet carriers stood ready. People moved around in the freezing morning—some with purpose, firing off orders through walkie-talkies; others anxious, waiting for the buses.

Departing military officers in dress uniform almost undid whatever composure we had left.

We held it together until the buses appeared, signaling our final moments together. Hugs and tears and determined whispers not to say goodbye, but “until the next time.” Entreaties to keep the heart of the community beating, to keep moving forward with the work.

Then they were gone—60 of our colleagues and their families. The rest of us dispersed reluctantly to pick up the pieces of our day. We had proven our resilience and strength in the way we performed the miracle of getting everyone out on the same flight, with all their pets, and with their household goods and cars following closely behind.

Moving Forward

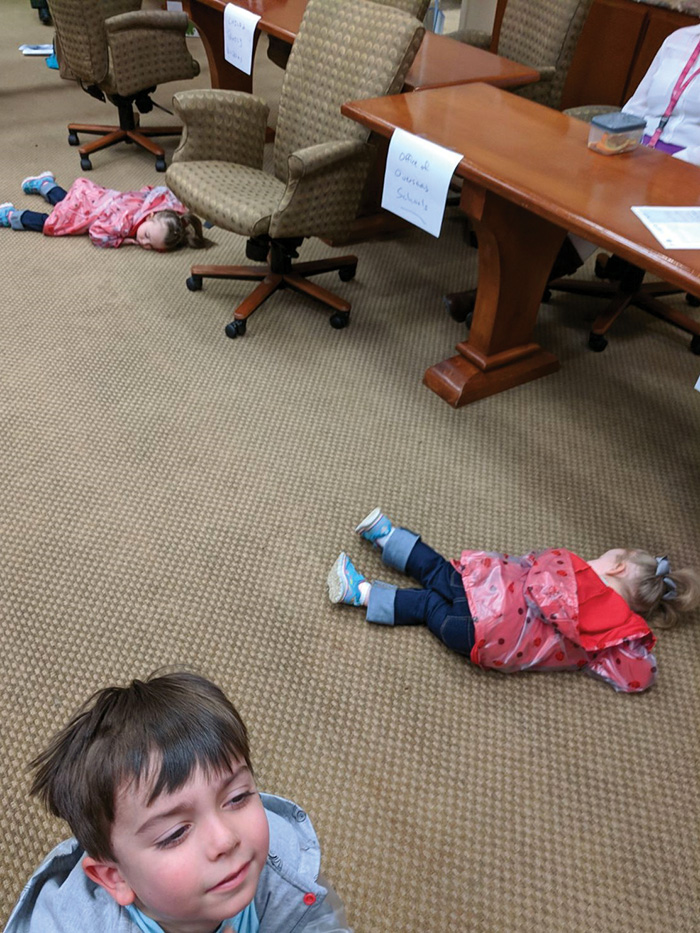

Back in the States, jetlagged children fall asleep without warning while their parents attend a meeting.

Aja Harris

After a relatively quiet departure from Sheremetyevo Airport in Moscow, the plane was met on arrival at Dulles with balloons, welcome home signs and the familiar faces of former Moscow officers and their families, many of whom themselves had been forced to leave last August.

A continent away, the Moscow community kept working. New social media platforms were formed to keep everyone in the loop. As our former neighbors landed at Dulles, photos of kids waving flags on the plane and reunions at Dulles were shared. Parents of jetlagged toddlers and babies met under the cherry blossoms in the D.C. dawn hours. Those same toddlers slept where they fell at morning information sessions arranged by our beloved CLO, who was determined to keep doing her job for the community from inside her living room at the Oakwood.

They are no longer front-page news, but those who were forced to leave continue to demonstrate extraordinary resilience. In their temporary D.C. apartments, they worry about an uncertain future. Personal effects may begin arriving, but many still face weeks without a future assignment, in some cases separated from family members still in Moscow. Tears have been shed, sleepless nights have been spent, and anxious conversations held.

There is nothing, it seems, that can keep this community down for long. We have survived not one, but two expulsions, and could write the manual on resilience, on how to survive separation and loss, on how to roll with the punches. Our community continues to thrive, to be a source of support and strength for those who are a part of it. There is no pretense in the courage of its members, playing the hand they have been dealt with dignity and grace.

On the Monday morning after the departure, our ambassador, Jon Huntsman, reminded those of us left behind of the need to link arms and carry on the work. Officers asked to take on the roles of their departed colleagues stepped up without complaint, determined to keep the embassy not just functioning, but moving forward.

The ambassador has stressed the importance of public diplomacy, of reaching out to the Russian people and seeing in them an echo of ourselves—the importance we all place on family, education, cultural identity and pride in country. These relationships we build will mend bridges between nations and rebuild political relationships.

More than one departing friend said that it would have been much easier to leave if they had hated Moscow. The truth is, we who live here love the city. That is also one of the strengths of the mission.

We are moving forward.

That is what we do.