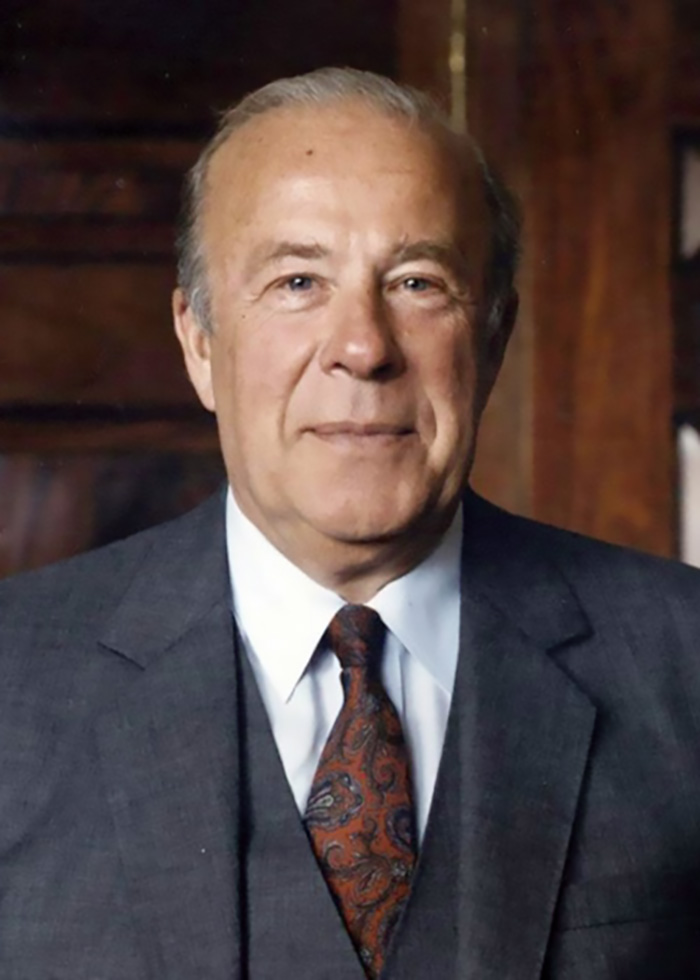

A Truly Trustworthy Leader: George P. Shultz, 1920-2020

BY STEVEN ALAN HONLEY

In December 1985, news broke that the Reagan administration was planning to require State Department employees to take lie detector tests to keep their security clearances. Expressing “grave reservations” about the validity of polygraphs, Secretary of State George P. Shultz threatened to resign if the policy change went forward, calling it a sign that “I am not trusted.” President Ronald Reagan took that threat so seriously that, after meeting with Secretary Shultz, he declared that he would leave it up to State Department officials to decide whether to administer polygraphs.

Although that incident did not change the status quo, and was soon forgotten by most people, it reveals much about George Shultz’s character. First, while he was a fully committed Cold Warrior, he instinctively understood that not every trade-off of liberty for security is warranted. Second, his background as an economist led him to value data over theory, so he saw no reason to trust polygraphs.

Third, he was intensely loyal to his employees, and they trusted him to have their backs. Although he couched his protest in personal terms (“I am not trusted”), everyone knew there was no chance he would ever be asked to take a lie detector test—let alone forced to do so to keep his job. But George Shultz understood full well that his subordinates at State did not enjoy that luxury, so he spoke out on their behalf—first through internal channels, then publicly.

For those reasons, and more, many Foreign Service members who served during Secretary Shultz’s tenure in Foggy Bottom (1982-1989) remember him fondly. (As far as I know, AFSA has never surveyed its members as to the Secretary of State they believe was the best leader of the department, but I’m willing to bet Shultz would come in at or very near the top of such a list.) A thoughtful institutionalist, he not only understood and valued the work of State and other foreign affairs agencies, but advocated for the resources and respect diplomats need and deserve.

In particular, he recognized the importance of professional education for the Foreign Service. When introducing Shultz at the May 2002 ceremony renaming the National Foreign Affairs Training Center as the George P. Shultz National Foreign Affairs Training Center, Secretary of State Colin Powell observed: “His is a name that the American people connect with selfless public service and solid integrity, a name that is synonymous with American statesmanship, a name that people all over the world recognize and which they associate with principled international engagement.”

Powell went on to note: “George Shultz is a student of history, and he has made quite a bit of it himself. We have always known George to be a man keenly focused on the future, especially on preparing the rising generation for service to the country. ... It is not we who honor George Shultz by naming this center after him; rather, it is George Shultz who honors us and all who will pass through these halls by lending his name to this facility.”

Long before George Shultz died at his home in Stanford, California, on Feb. 6 at the age of 100, he had validated Powell’s prediction. Survivors include his wife, Charlotte Mailliard Shultz, as well as five children, 11 grandchildren and nine great-grandchildren.

The Road to Foggy Bottom

George Pratt Shultz was born in New York City on Dec. 13, 1920. He graduated from Princeton University in 1942 with a bachelor’s degree in economics, and then joined the U.S. Marine Corps, serving through 1945. He received a Ph.D. in industrial economics from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1949.

Shultz spent most of the next two decades in academia. He taught at MIT from 1948 to 1957, but took a year’s leave of absence in 1955 to serve as senior staff economist on President Dwight Eisenhower’s Council of Economic Advisers. In 1957 he was appointed professor of industrial relations in the University of Chicago’s Graduate School of Business, and he became dean of the school in 1962. From 1968 to 1969, he was a fellow at the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences at Stanford University, the beginning of a long association with that institution.

Shultz served in the administration of President Richard Nixon as Secretary of Labor from January 1969 to June 1970, at which time he was appointed director of the Office of Management and Budget. He became Secretary of the Treasury in May 1972, serving until May 1974. During that period, he also served as chairman of the Council on Economic Policy and chairman of the East-West Trade Policy Committee. In that capacity, Shultz traveled to Moscow in 1973 and negotiated a series of trade protocols with the Soviet Union. He also represented the United States at the Tokyo meeting of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade.

In 1974 he again left government service to become president and director of the Bechtel Group, where he remained until 1982. While at Bechtel, he maintained his close ties with the academic world by joining the faculty of Stanford University on a part-time basis.

George P. Shultz was a key player, alongside President Ronald Reagan, in changing the direction of history by using the tools of diplomacy to bring the Cold War to an end.

–The Hoover Institution, Feb. 7, 2021

From January 1981 until June 1982, when he was nominated to succeed Alexander Haig as Secretary of State, Shultz was chairman of President Ronald Reagan’s Economic Policy Advisory Board. He was sworn in as the 60th U.S. Secretary of State on July 16, 1982, during a period of especially icy relations between the world’s two remaining superpowers, yet he immediately began pushing for a broader dialogue between the United States and the Soviet Union.

When Mikhail Gorbachev became general secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in 1985, Shultz was convinced Gorbachev was a new type of leader—one who understood the importance of nuclear arms control. “He helped Reagan and Gorbachev to establish an upward spiral of trust by creating positive experiences with each other,” historian Stephan Kieninger wrote for the Hoover Institution at Stanford University as part of the celebration of Shultz’s 100th birthday in December.

Those talks eventually led to the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, which banned land-launched nuclear weapons capable of reaching targets between 310 and 3,400 miles away. Reagan and Gorbachev signed the agreement in 1987. By June 1991, the two countries had destroyed 2,692 ballistic and cruise missiles.

There is no dispute that, as Stanford’s Hoover Institution said in announcing his death, “Shultz was a key player, alongside President Ronald Reagan, in changing the direction of history by using the tools of diplomacy to bring the Cold War to an end.” He was able to “not only imagine things thought impossible but also to bring them to fruition, and forever change the course of human events.”

As Secretary of State Antony Blinken observed in his own tribute on Feb. 7, his predecessor “not only negotiated landmark arms control agreements with the Soviet Union, but after leaving office he continued to fight for a world free of nuclear weapons. He also urged serious action on the climate crisis at a time when too few leaders took that position. He was a visionary.”

After State

Returning to private life in January 1989, Shultz rejoined Stanford University as the Jack Steele Parker Professor of International Economics at the Graduate School of Business. He was also the Thomas W. and Susan B. Ford Distinguished Fellow at the Hoover Institution.

Awarded the Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor, on Jan. 19, 1989, he also received the Seoul Peace Prize (1992), the Eisenhower Medal for Leadership and Service (2001), the Reagan Distinguished American Award (2002) and the American Foreign Service Association’s Lifetime Contributions to American Diplomacy Award (2003).

Secretary Shultz published several books and countless monographs, articles and op-eds between 1953 and 2020, including a best-selling memoir of his time in Foggy Bottom: Turmoil and Triumph: My Years as Secretary of State (Scribner’s, 1993).

In November 2020, The Foreign Service Journal’s cover story was an essay by Secretary Shultz titled “On Trust,” later excerpted in The Washington Post, The New York Times and elsewhere. And in December, for his 100th birthday, the Hoover Institution published a related monograph by Shultz, “Life and Learning after One Hundred Years—Trust Is the Coin of the Realm: Reflections on Trust and Effective Relationships across a New Hinge of History.”

In the monograph, the former Secretary of State summarizes the philosophy that animated his approach to international relations, both at State and beyond: “Genuine empathy helps to create sound relationships across countries, even when cultures seem far apart and when times are tough. Our country will face fresh challenges in an emerging new world: new pandemics, new technologies, new weapons, environmental change, demographic change, and the ever-renewing charge to effectively govern over diversity. A shared understanding, and a human connection, will help us navigate these unsettled waters.”

On Feb. 10, Senators Dan Sullivan (R-Alaska) and Chris Van Hollen (D-Md.), co-chairs of the Senate Foreign Service Caucus, introduced a resolution honoring Shultz’s life, achievements and legacy. “Statesmanship and service above self consistently characterized the remarkable life of George P. Shultz,” said the senators. “Throughout his distinguished career, Secretary Shultz championed American diplomacy and strengthened its home institution—the Department of State—all in pursuit of a more peaceful, prosperous and cooperative world order. Secretary Shultz’s example as a patriot and public servant will undoubtedly serve to inspire and guide future generations of American leaders.”

In honor of George P. Shultz, The Foreign Service Journal invited members of the Foreign Service who knew and worked with the former Secretary of State to send us their remembrances. This living memorial is on the AFSA website at afsa.org/remembering-george-shultz.

For more articles on George P. Shultz from the FSJ Archive, please visit our special collections page at afsa.org/fsj-special-collections.