On Trust

A distinguished statesman shares his thoughts on the path ahead, starting with the importance of rebuilding trust.

BY GEORGE P. SHULTZ

George Shultz walks with President Ronald Reagan outside the Oval Office on Dec. 4, 1986.

Ronald Reagan Presidential Library, NARA

Secretary of State George Shultz meets staff at Embassy Moscow ahead of the May 1988 Moscow Summit meeting between President Ronald Reagan and General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union Mikhail Gorbachev.

Shawn Dorman

Now in my hundredth year, I am impelled by recent events to offer my thoughts about what I have come to believe is as crucial an element in public life as it is in private life. I am thinking about trust. We all instinctively, or from personal experience, know that good neighborly relations thrive when neighbors trust one another, and that life can become miserable if trust is replaced with suspicion and doubt. Trust is perhaps a more complex factor in life between communities and nations, but it is just as critical in determining whether cooperation or conflict—or even war or peace—will dominate the relationship.

I have become deeply concerned in these last few years that distrust has become a common theme in our domestic life. It is now accepted as normal that our two great political parties rarely find common ground and that legislation to advance the well-being of American citizens can be achieved only under the pressure of a great life-or-death crisis like the COVID-19 pandemic. It has taken a nationally circulated video of a Black man’s atrocious murder by a police officer—whose duties included training newcomers to a major American city’s police department—to reveal the depths of racial distrust that exist in our country.

Our relations with much of the rest of the world also have become characterized by distrust bordering on hostility, even in the way Washington deals with close allies in Europe and Asia. We are nearing a Cold War II situation in our relations with China and Russia. Reliance on military threats, with little or no effort at diplomacy, is the most prominent feature of our relations with nations that we associate with anti-American sentiments and actions.

What Trust Means

Trust among nations or between those who represent their nations in official discourse with other nations should not be equated with burgeoning friendship or a change in fundamental beliefs on either side. The idea implies a belief that what a nation or a public official commits to do will, in fact, be done. That means not only that honesty has become the accepted norm but also that what a nation or its official says will happen is, in fact, capable of being done; that is, the commitment is precise enough to measure its implementation, and the authority to carry out the commitment is assured.

As President Ronald Reagan’s Secretary of State, I had the president’s backing to change the arms control paradigm from “capping” the buildup of U.S. and Soviet strategic nuclear forces to one of beginning to actually reduce the levels of forces. We succeeded, with the cooperation of General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev, in turning around the nuclear buildup so that 1986, the year of the Reagan-Gorbachev Reykjavík Summit, became the high-water mark for the world’s nuclear weapons instead of just another year of more and more nuclear bombs and warheads.

Trust was key to reaching these agreements. The American president and his Secretary of State became convinced that Mikhail Gorbachev was a new type of Soviet leader, one who shared their concerns about nuclear weapons and could be trusted to carry out agreements. Of course, we used a Russian proverb to stress that verification had to be a part of the deal: “Trust, but verify.” That brings us to another point about the meaning of trust: It has to be earned, which means that it has to be based on undertakings that can be seen to be carried out.

After nearly four years of an administration that seems to have assumed that American relations with the rest of the world is a zero-sum game and that the game is based largely on the personal relations between national leaders, distrust abounds internationally. The ability of the United States government to execute the president’s foreign policies has become severely limited by the lack of a clear and coherent method of formulating policy. The president’s use of social media to make frequent public reversals and revisions in policies has made the job of America’s diplomats exceptionally complex.

I see a need in the coming years to rebuild trust where now it is absent, based on policies that defend and advance American interests and ideals. The international system is constantly being reshaped; right now, trends in technology and economics, and even the pandemic, are having a major impact on how our country interacts with the rest of the world. With skillful diplomacy and visionary leadership, we can influence these trends and help to create an international system consistent with our values. Our partners in this effort will have to regain trust that we do, indeed, share the same democratic values, and that we really are working for an international system of nations that benefits all of us. Even our adversaries will have to regain the trust that we can work together to manage global threats to humanity’s very existence even when we disagree on other issues. This task may require more than a single presidential term to accomplish.

The Role of Strategic Thinking

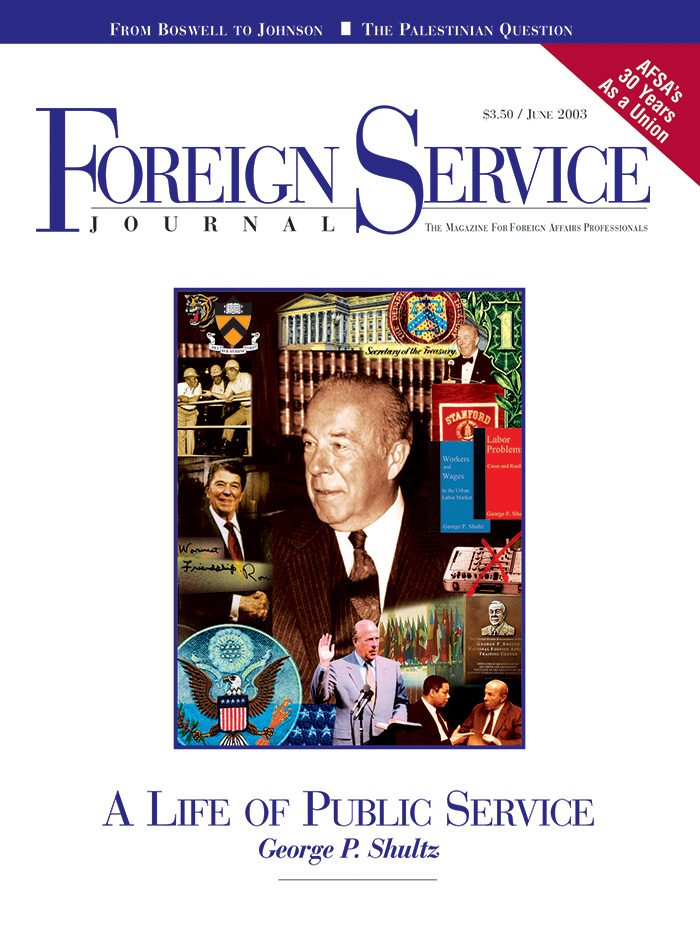

During his tenure as Secretary of State from 1982 through 1989, George Shultz featured on the cover of The Foreign Service Journal several times. The June 2003 FSJ celebrates his receipt that year of AFSA’s highest award, for Lifetime Contributions to American Diplomacy.

At the beginning of Ronald Reagan’s second term, the Senate Foreign Relations Committee invited me to talk with them about the future and how American foreign policy might shape a world to our liking. I gladly met with them on Jan. 31, 1985. I recommend that the Senate convene a similar meeting in January 2021, or whenever a new Secretary of State is in place, because strategic thinking is critically important in policymaking and we have to get back in the habit or, as some observers might say, break new ground.

In my remarks on that January day 36 years ago, I said “history never stops,” adding that “our duty must be to help shape the evolving trends in accordance with our ideals and interests.” Another point I made in my talk with the Foreign Relations Committee that day is one that I want to expand on because it bears on the rebuilding that must take place in the federal government in general, and in the State Department and its Foreign Service, in particular. Referring to the new developments of those days, I said: “Our ways of thinking must adapt to new realities; we must grasp the new trends and understand their implications.” I stress this point because to me an important implication of recent trends is that rebuilding the State Department and its Foreign Service, like nearly all the rest of the federal government, cannot mean simply replicating what was there in the Obama and Bush and earlier administrations.

Technology has empowered American citizens so that they can make their views known through social media and organize movements in the same way. This has changed the way politics and policymaking work in our country and elsewhere. Representative democracies have all reacted to these changes, although in different ways, and their diplomacy must reflect those changes. Most governments, and I would say our own included, have not caught up with new realities. The people who succeed the present generation of civil servants and members of the Foreign Service will be familiar with the new realities because they will have been part of them during much of their lives; but the ways in which the future leaders of the State Department and its Foreign Service manage the professional development of incoming diplomats and policy advisers will require changes, and that is really hard to do.

I was very pleased that during my tenure as Secretary of State, a National Foreign Affairs Training Center was established that absorbed the Foreign Service Institute, and I was proud that the center was given my name. As a former educator at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the University of Chicago and Stanford University, I cherished this legacy, and still do. One of the priorities of 2021 should be to review the resources devoted to the center in light of educational goals appropriate to the new realities.

A few years ago, the U.K. government decided to create a British Diplomatic Academy for the first time in the long history of British diplomacy. Probably in recognition of the fact that foreign policy, both in its making and its execution, had become dispersed through several ministries, the stated goals of the new academy included the vision of “a Foreign Office that is an international center of ideas and expertise; that leads foreign policy thinking across government.” Another stated goal, one more aimed at acquiring the people who could achieve this vision for the Foreign Office, was to become “the best diplomatic service in the world.” Other nations have had diplomatic academies for many years, and they have sought more modest goals. The German diplomatic academy focuses on purposefully and strategically networking with counterparts from other nations. The French academy places high value on mentoring junior officers.

The Making of Career Diplomats

FSJ Editor Shawn Dorman congratulates Secretary Shultz at the AFSA awards ceremony in June 2003 when he was honored with the award for Lifetime Contributions to American Diplomacy.

AFSA

There are lessons to be learned from other countries about the professional education of America’s diplomats, but of course our academy has to be rooted in the American experience. In the period of rebuilding that lies ahead, I hope that the State Department and its Foreign Service will take a close look at the professional formation of career diplomats. One thing I learned as Secretary of State was that the culture of the Service did not reward people with promotions or postings for the efforts they made to improve their knowledge base by taking courses at the Foreign Service Institute or at universities. In a promotion system where failure to achieve promotions results in dismissal from the Service, this attitude is a powerful disincentive to spend much time in educational institutions. I hope that attitude is changing, because there is a large body of knowledge that our diplomats should have mastered or at least have some familiarity with that is not easily acquired these days even in universities. I am thinking of area studies, the history and practice of international negotiations and, of course, a working knowledge of exotic languages.

It is tempting to believe that good diplomats are born, not made, and that our recruiting system should simply find such people and the rest will take care of itself. There is some truth in this, because the personal qualities of integrity, empathy, problemsolving attitudes and the ability to build trusting human relationships are critical to success as a diplomat. Traits like these, plus courage, determination and patriotism, are what made Marie Yovanovitch such an effective American ambassador to Ukraine. She had other credentials, too, that enabled her to go to the top of her profession, one that, like other professions, requires a solid background in specialized knowledge.

My sense is that incoming members of the U.S. Foreign Service should be required to participate in a full academic year of professional education at the National Foreign Affairs Training Center. There might be a distinct part of the center that could be called “The School of Diplomacy.” A diverse group of future American diplomats would benefit, I think, from the integrating effects of a common learning experience. That said, there should also be separate courses in area studies and languages. The common program should include a feature pioneered by the now defunct Senior Seminar, a course that gave diplomats an introduction to various slices of American life. Personally, I would like to see the common course include case studies in diplomacy and many opportunities for extended talks with senior American diplomats and with those of other nations, too. As a former teacher myself, of course I have an interest in curriculum, and so I would be pleased to meet with people who are giving serious thought to what is suitable for today’s realities.

I want to be clear that I am not criticizing the very good people in the State Department and the Foreign Service who, so far as I can see, are conducting themselves in a way that should make the American people proud of them. Nor do I mean to impute malign intent to the leaders of the current administration. Several issues that will need to be addressed in a rebuilding program antedate this administration, the impact of social media on our national conversation being one. I have always believed that in the end, and probably after much impassioned debate, our national security must rest on a nonpartisan consensus framed by our shared values. So let it be in this case.

Read More...

- “Groundbreaking Diplomacy: An Interview with George Shultz,” by James Goodby, The Foreign Service Journal, December 2016

- “A Life of Public Service: George P. Shultz,” by Steven Alan Honley, The Foreign Service Journal, June 2003

- “George P. Shultz: Learning From Experience,” Hoover Institution, July 21, 2020