U.S. Consul Thayer’s Beethoven

The best biography of the great Ludwig van Beethoven was written by a U.S. diplomat in the late 19th century. Here is the story.

BY LUCIANO MANGIAFICO

In the early years of the 19th century in music-crazy Europe, Ludwig van Beethoven—as a composer, conductor, and pianist—was the epitome of the mad, romantic genius. His wild looks, love of nature, unorthodox and quirky behavior, mercurial temperament, and self-awareness that he was a groundbreaking composer, made him widely recognized throughout the world, and when he died in 1827, everyone knew that a supreme musical wizard was gone.

You would think that such an interesting personality would have drawn biographers to him to begin writing about his life, and, of course, several were: Anton Schindler, a violinist and Beethoven’s factotum; Ferdinand Ries, a composer and Beethoven’s secretary; and Franz Wegeler, a German physician and Beethoven’s friend. The biographies they wrote, however, while interesting, were not entirely accurate and were often contradictory in many details.

It was not until 1907-1908 that a five-volume accurate and complete Beethoven biography was published in Germany. It was the work of Alexander Wheelock Thayer, the longtime U.S. consul in Trieste. Thayer completed and published the first three volumes himself, while his translator and a fellow musicologist finished the last two after Thayer’s death.

Despite the passage of time, Thayer’s is still the best and most complete personal (as opposed to musical) biography of the great composer.

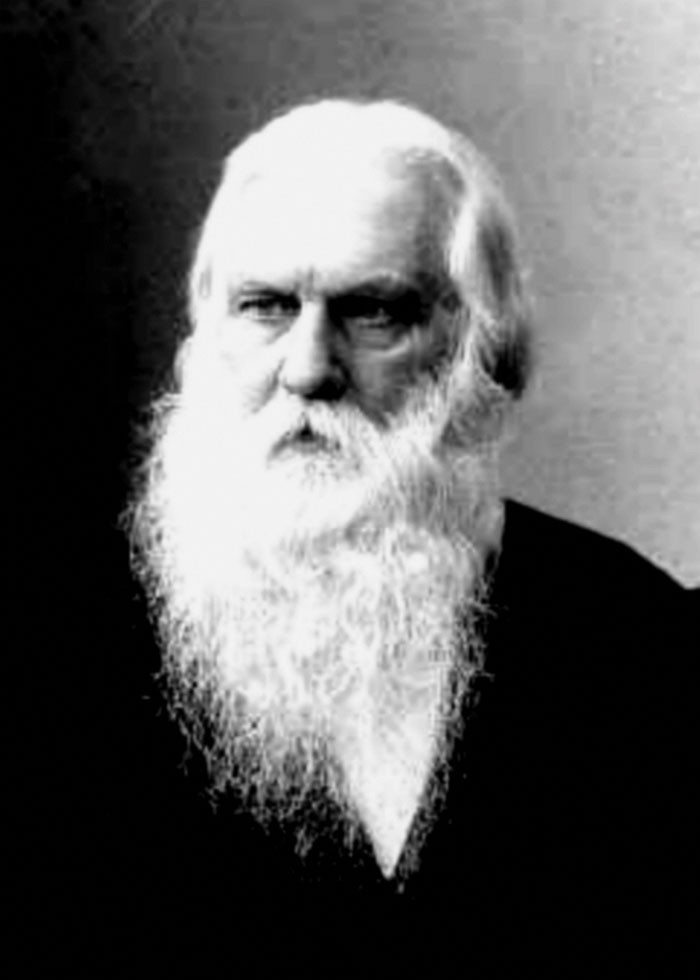

Alexander Wheelock Thayer.

Wikimedia

Alexander Wheelock Thayer was born in South Natick, Massachusetts, in 1817. After graduating from Phillips Academy in Andover, he attended Harvard College but did not graduate until 1843, when he was 26 years old. He stayed on, and two years later obtained a law degree from Harvard Law School. While attending Harvard he had worked in the library, where his interest in music was heightened, and he began collecting research material on Beethoven.

Classical music in Boston, and Beethoven symphonies in general, were then the rage, and the Boston Academy of Music, established in 1833, performed Beethoven frequently beginning in 1841, so much so that musicologist Joseph Horowitz devoted a section to “Boston and the Cult of Beethoven” in his book Classical Music in America (2005).

In 1849 Thayer went to Germany for two and half years, traveling about, learning German, and doing research on Beethoven’s life because he intended to translate Schindler’s biography into English. To support himself, he wrote articles on music and culture for the Boston Courier. In 1852 he returned home and continued to write for publications, but in 1854 returned to Europe once more to pursue his Beethoven research. A little later, he decided that he would write a new Beethoven biography, in English, and have it translated and published in Germany. He also continued to write musical criticism and history, publishing articles on Beethoven, Antonio Salieri (Mozart’s alleged enemy), and others.

Thayer began his diplomatic career in 1862 at age 45, with the help of Senator Charles Sumner (R-Mass.), a fellow Harvard alumnus. Thayer first obtained a position as secretary of legation in Vienna; and then, on Nov. 1, 1864, President Abraham Lincoln nominated him U.S. consul in Trieste. At that time, Trieste was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and a major cosmopolitan port for Austria. Thayer assumed the post on Jan. 1, 1865, and kept it for 17 years until he resigned on Oct. 1, 1882. In 1866 President Andrew Johnson submitted Thayer’s name for appointment as consul in Vienna, which would have made it much easier for Thayer to continue his research on Beethoven, but the U.S. Senate failed to confirm him.

By the time Thayer joined the diplomatic service, according to the Act of Congress of March 1, 1855 (10 U.S. Statutes 619), consular officers, whose main duties were those now performed by commercial attachés, had become salaried government employees. This relieved Thayer of financial worries; and, while his subordinates and clerks carried on most of the consular duties, he was able to continue his research and write his Beethoven biography.

It was not unusual for presidents to appoint literary figures to diplomatic and consular posts, providing security of income and allowing them to pursue, concurrent to their duties, their avocations. Thus, we had Washington Irving and James Russell Lowell as ministers to Spain; Edward Everett, George Bancroft, and John Lothrop Motley as ministers to Great Britain; Lew Wallace as minister to Turkey; Nathaniel Hawthorne as consul in Liverpool; and William Dean Howells as consul in Venice.

Other countries also had consuls with a literary bent in Trieste. Stendhal had been French consul there for a few months in 1830-1831, and in 1867-1872 the British man there was Charles Lever (1806-1872), a prolific novelist who once rivaled Dickens in popularity. Lever was succeeded as British consul by none other than Sir Richard Burton, the explorer and author, who was there from 1872 until his death in 1890.

A portrait of Ludwig van Beethoven by Joseph Willibrord Mähler that was once owned by Alexander Thayer and now belongs to the New York Public Library.

New York Public Library

While not neglecting his duties, during his earlier life in Germany and his occasional trips from Trieste, Thayer had interviewed virtually everyone still alive who had known Beethoven, read all available biographies, studied Beethoven’s surviving conversation books and any pertinent documents, and kept copious notes. He began to write his magnum opus in English, entrusting the translation to German educator and musicologist Hermann Deiters (1833-1907). The first volume of Life of Beethoven was published, in German, in Berlin in 1866; the second came out in 1872, and the third in 1879. Thayer was still working on the remaining volumes when he died in 1897. The fourth volume was being finished by Deiters when he died in 1907, and both this volume and the fifth were completed from Thayer’s notes by composer and musicologist Hugo Riemann (1849-1919) and published in 1907-1908.

While Thayer’s guiding principle was “an ounce of historical accuracy is worth a pound of rhetorical flourish,” his prose is anything but dry. He also succeeded in his biographic endeavor because, as he told his translator, Deiters, “I have resisted the temptation to discuss the character of Beethoven’s works and to make such a discussion the foundation.” He avoided discussions of the philosophy, meaning, structure, and evaluation of Beethoven’s opus, and concentrated on his personality and life events, except for, in the Victorian era, prying into his sentimental life. Thayer showed both sides of Beethoven’s character: the musical genius and generous man, his aesthetic, groundbreaking vision and his sweetness, as well as his uncouth, abrupt manners, his occasional dishonesty, and his litigious, controlling misanthropy. He was, indeed, angel and devil at the same time.

The first English edition of the work, assembled from Thayer’s original manuscript, his notes, and the published German translation, was published in 1921. Its author was American musicologist and music critic Henry E. Krehbiel (1854-1923), who commented: Thayer’s “industry, zeal, keen power of analysis, candor, and fair-mindedness won the confidence of all with whom he came into contact except the literary charlatans whose romances he was bent on destroying in the interest of the verities of history.”

More than 100 years later, Thayer’s is still the definitive biography of Beethoven. The eminent literary critic Van Wyck Brooks wrote: “The work was a characteristic product of the Yankee mind [when] hero-worship flourished in Boston. … Thayer conceived his passion for Beethoven while still at Harvard. All the existing accounts of the composer were a tissue of romantic tales and errors, and Thayer resolved at once to write the great biography. … Thayer’s life of Beethoven had long been a German classic when it first appeared in America in 1920. … [W]ith his calm and logical mind, scrupulous, magnanimous, and spacious … [he] had set out to describe for posterity the great man as he was …with all his warts; and his patient realism and all but inexhaustible industry had created an irreplaceable and masterly portrait.”

The latest reprint of Thayer’s Life of Beethoven (1967), updated with the latest research and newly discovered material, was that of musicologist and conductor Elliot Forbes (1917-2006).

Classical music in Boston, and Beethoven symphonies in general, were then the rage.

In addition to being the site where the biography was written, Trieste shares two other links with Beethoven. The composer’s famous piano sonata, Moonlight, Opus 27, Number 2 (1801-1802), was dedicated to Countess Giulietta Guicciardi (1784-1856), a young lady with whom the 30-year-old Beethoven had fallen in love. Guicciardi had just moved to Vienna from Trieste and was taking piano lessons from the composer.

The other link is the greatest collection of Beethoveniana. Not located in Bonn, where he was born, or in Vienna, where he became famous, the museum is in Muggia, a small town across the Gulf of Trieste. Its contents were assembled during the last 40 years by the Carrino family, who converted their villa into a Beethoven museum.

In Trieste, Thayer, who never married, lived in an apartment cared for by a housekeeper on the seafront promenade and, as a Carthusian monk, dedicated most of the last 40 years of his life to his project. Even after retiring from the consulate in 1882, he stayed put in Trieste, continuing his routine as much as his health allowed him.

Despite his long residence in Trieste, where the majority of the inhabitants spoke Italian, he never learned the nuances of that language, one time being embarrassed at a dinner by not recalling momentarily the Italian word for “spoon.” His research and his prior life in Germany had made Thayer’s personality more attuned to German culture and speech, and he was often taken for German, rather than American. Apart from people in the musical world, his friends in Trieste included Sir Richard Burton, who, like Thayer, died in that city.

Alexander Thayer’s death in Trieste in July 1897 was big news, particularly in Germany. His library and Beethoven memorabilia were sold by his inheritors at auction both in New York and in London in 1898 and 1899. Thayer also left $30,000 to Harvard, his alma mater, to be used for scholarships.

He was buried in the Protestant Cemetery of Trieste, and, over time, his tomb was either forgotten or believed lost. Then in 1964, John P. Sabec, an employee of the American Consulate General in Trieste, with the assistance of local historian Oscar De Incontrera (1903-1970), found it. Sabec then began to clear out the vegetation grown on the tomb and involved Vice Consul Samuel E. Fry (b. 1934) and Consul Samuel G. Wise (b. 1928; later ambassador).

Money was raised, and back and future rent on the cemetery plot paid. The marble tombstone had previously given only his name and the dates and places of birth and death; Vice Consul Fry then paid a sculptor to add: “Biographer of Ludwig van Beethoven—American Consul in Trieste 1865-1882.” Nearby are also buried Stanislaus Joyce, James Joyce’s brother, and Achille La Guardia—father of Fiorello La Guardia, a former U.S. diplomat, congressman, and mayor of New York.

When sharing or linking to FSJ articles online, which we welcome and encourage, please be sure to cite the magazine (The Foreign Service Journal) and the month and year of publication. Please check the permissions page for further details.

Read More...

- “Our Man in Fiume: Fiorello LaGuardia’s Short Diplomatic Career” by Luciano Mangiafico, The Foreign Service Journal, March 2015

- “Israelit Friedhof: A Forgotten Cemetery in Vienna” by Jeffrey Glassman, The Foreign Service Journal, May 2016

- “The Short Diplomatic Career of Mordecai Manuel Noah” by Luciano Mangiafico, The Foreign Service Journal, September 2022