Third Culture Kids: The Enduring Effects of Formative Years in Cairo

Long after retirement, a group of TCKs who were grade-school classmates in Egypt reunited online. Here they tell their story.

BY MARY MARIKO MURO, JILL P. STRACHAN, AND JOHN R. WHITMAN

The cover of the Cairo American College 1963 yearbook features the driveway lined by royal palms leading to the front entrance to the school, a former palace previously occupied by Princess Hanezada and her family, situated in Cairo’s leafy suburb of Maadi.

Courtesy of John R. Whitman

It all started with an article about Cairo’s antique elevators by Vivian Lee in The New York Times on Sept. 20, 2021. One of our classmates from primary school at Cairo American College (CAC) more than 60 years ago had, amazingly, found email addresses for many of us. He sent around this amusing account of up-and-down “scenes of love and fear,” suspecting it would evoke a special feeling among his peers who had shared the experience of Cairo together as preteens.

Then they began to respond from Oslo; Paris; Tokyo; Tucson, Arizona; Monte Rio, California; Washington, D.C.; St. Augustine, Florida; Chicago, Illinois; Cushing, Maine; Newfield, New York; and Port Ludlow, Washington. Their emails recounted anecdotes of elevator experiences in Egypt, which led, in turn, to encounters with lifts in Paris, followed by other stories. Sounded like an interesting group. What if we all met up on Zoom?

The invitation struck a chord. Perhaps it was the hunger to connect with others during the COVID-19 pandemic, combined with curiosity about what ever happened to that kid on the school bus from Zamalek or at the Maadi Sporting Club pool.

Seeing a former schoolmate you haven’t set eyes on in 60 years is a kind of wake-up call. First, of course, you see how a child you thought you would always remember as a child has transformed into an adult approaching seniority, like yourself! And then the reawakening expands your consciousness, recalling the vivid, sometimes momentous times you spent together living the dream of climbing the pyramids, riding Arabian horses across the Sahara, partying in Bedouin tents, hearing the evocative call of the muezzin, gazing at the timeless image of feluccas gliding on the Nile, experiencing the warmth of Cairenes and the heat of their sun, and surviving those idiosyncratic elevators in your shared childhood. The bond of being a third culture kid (TCK) is real.

Every month now, going on two years, we all dial in for a couple of hours of revivified camaraderie and talk about what these experiences meant to us and how we and our families have advanced since those ephemeral years in the land of the pharaohs. One of us volunteers to present a “Cackle” (derived from the “Cairo American College Kick-off Lecture”), which is a short talk about one’s current personal or professional activities or a reflection on our time in Egypt or other, more current world events. After opening chatter, the Cackle lasts about 20 minutes, followed by Q&A or general discussion. The sessions begin at 8:30 a.m. Eastern Standard Time to accommodate those living in time zones extending from Japan to Europe. Sessions are recorded for the benefit of those who miss an event.

Every Cackle has enriched us. Some have led to follow-up email transactions and a deeper dive informed by further research. So far, we have shared taking pilgrimages in Spain and Italy, observing elections in Bosnia, living life as an astrologer with an internet following, and being an American journalist in Berlin, Bonn, Hong Kong, Moscow, New York, Rome, and Warsaw during or after the Cold War.

We have enjoyed Cackles recounting the flight of Norwegian royals to London to escape the Nazis, on learning to become an Egyptologist, the importance of learning a second language, the psychosocial characteristics of TCKs navigating the conflicts between the culture of their foreign experiences and that of their home countries, the identity challenges of being an adopted TCK, the demise of academic standards in leading universities, and the rigor required to learn from the literature of the Ottoman Empire. And we have discussed lifelong lessons from experiencing childhood trauma, enduring the devastation of drugs and rootlessness, and more.

Ten of the 15 original members of the group, including the three authors, in a Zoom meeting in April 2023. From top left to bottom right: Mary (Marika) Muro, John R. Whitman, Alain Cardon, Jeff Peters, Nanako Nakamura, Susan Shaffer, Andrew Nagorski, Jill Strachan, Kirsten Rytter, and Marla Kean Hensley. Missing are Patrick Cardon, Richard Driscoll, Cornell Fleischer (deceased, April 21, 2023), Seibun Tanetani, and Andrea McCoy Van Dyke.

Courtesy of John R. Whitman

Connecting as Grown TCKs

This contrived reassembly of once-carefree boys and girls has become an important part of our lives. Some of us are compelled to attend the meetings regularly, and even those too busy to join want to stay tuned. We wondered why, and we put the question to our colleagues. Here are some of their responses.

I was born in Scotland to Polish parents, moved to the United States as an infant, and rarely stopped moving since. Soon after my father became an American citizen, he joined the U.S. Information Service (USIS), serving as a press attaché in Cairo, Seoul, and Paris where I attended American schools—all of which made my subsequent life as a foreign correspondent feel very natural. The initiative by some of my Cairo schoolmates to reconnect so many years later brought back a flood of memories, not just of Egypt but of other postings: riding horseback by the pyramids, getting my first exposure to tear gas while observing South Korean students protesting against the regime of military strongman Park Chung Hee, and celebrating the end of my senior year at the American School of Paris prom at the Eiffel Tower. My father, who often handled the programs of prominent American visitors, introduced me to the likes of Louis Armstrong and Robert Kennedy.

All those experiences felt almost normal until I returned to the United States on our home leaves or, later, to attend college. I quickly realized that I could not casually sprinkle in such stories without looking like I was showing off to my new acquaintances, most of whom had grown up in more conventional circumstances. But none of those problems exist when you are in the company of others who have similar backgrounds. That’s why our virtual Cairo reunions are always so enjoyable.

—Andrew Nagorski, St. Augustine, Florida

A farewell party for Susie and Johnny Shaffer (seated on couch) arranged by the Anschuetzes’ daughters, Susan (holding dog) and Nancy (seated next to Susie).

Courtesy of John R. Whitman

Kirsten Rytter dancing The Twist with Richard Driscoll, after release of the Chubby Checker hit song, 1959 or 1960. Party games included musical chairs and spin-the-bottle.

Courtesy of John R. Whitman

For my part, although our circle’s presentations are often well prepared and quite scholarly, attending our group is akin to going to a family reunion, where we can tune into each other’s feelings and hearts, and where we can share events and experiences in a way we may not do otherwise. Not only do we share our common past but also all that may be of significance that has happened since, always with loving respect.

—Alain Cardon, Paris

Little did I know that reconnecting through Facebook with my childhood Norwegian friend from 6th, 7th, and 8th grade in Cairo would then lead me to this whole new circle of friends from those magical days at CAC! It has awakened memories and motivated me to read through the saved letters my mother wrote of life in the Foreign Service. The term “TCK” was new to me, and this really explained some disconnect with friends in the U.S.

Sharing our experiences and commonalities has been cathartic and humorous. The Cackles are fascinating and produce amazing discussions from personal struggles and perseverance to broad topics where the expertise in the group shines as they mimic an international think tank. This summer I visited Kirsten in Norway after 54 years apart, and we instantly bonded again. I’ve also made strong connections with other classmates whom I barely remember from the 1960s, but now we are talking about visiting each other in Japan and across the U.S.

—Marla Kean Hensley, Tucson, Arizona

I take great comfort from the reaffirmation of meeting those who shared the same classroom during budding adolescence at a school housed in a former palace near the edge of the desert. The Cackle sessions became one place where we didn’t have to keep quiet about our unique childhood and, instead, could be accepted for what we really are. For me, personally, the sessions became a way not only to reach my childhood classmates, but also to be with other adult third culture kids [ATCKs] and speak the language that comes more naturally to me. It was also very encouraging to see firsthand what fine human beings my former classmates had become.

—Mary Muro, Tokyo

I have to add the memory of learning French while overcoming the distraction of camels snorting outside my classroom at CAC. My heritage and my U.S. Foreign Service childhood gave me many remarkable opportunities, but until later in life, I downplayed them to fit in with my U.S. peers and colleagues. By way of our Cackle discussions, I realized the power of the TCK model and am experiencing a coming out (the second in my case) that has opened a flood of memories and resurrected former connections dating back almost 60 years. Imagine my surprise and joy.

—Jill P. Strachan, Washington, D.C.

One difficult aspect of being a preteen and teen TCK is the cycle of Foreign Service posts. During eight years in France, where Dad was heading up Marshall Plan public relations before joining Voice of America, we lived a dulcet life in a village along the Seine with home leave every two years. Then came Cairo. Upon arrival, I was transfixed; clearly, Egypt would be a keeper for the rest of my life. At CAC, there were more than 200 students in kindergarten through high school from some 16 countries. Unlike in the U.S., French and Arabic were no longer foreign languages. Students were welcoming, friendships were blossoming. But sadly, with postings often just two years, goodbyes were common. We were just getting close, then off my friend went. I got good at hiding the pain by not showing up. Decades later, “Cairo elevators” arrived, distilling years of separation into an elixir of reacquaintance filled with memories still sweet.

—Richard G. Driscoll, Newfield, New York

Seeing a former schoolmate you haven’t set eyes on in 60 years is a kind of wake-up call.

When my family lived abroad, we always spoke of Norway as “home.” Now connecting with old friends in the Cackle network is like coming home. A place to share childhood experiences, discovering that the American kids also sometimes felt that their childhood experiences were sort of out of place. The group’s success is due to the interesting topics that are brought up in the introductory part by the network members. Having an effective moderator helps.

—Kirsten Rytter, Oslo

Spun out like yo-yos with very long strings, each of us were launched into the life journey and discovered ourselves enmeshed in a version of a cat’s cradle for a season near Cairo, Egypt. Once again, then, we were projected off to the far reaches of the planet to expand the potential entanglement of that cradle. Over the past couple of years, the return cycle back along varied paths, we discovered ourselves bouncing within each other’s spheres in closer proximity. The kaleidoscope of world adventure brought to the table each month has rekindled aspects of our childhood and onward travails that have been a delight to share.

—Jeff Peters, Port Ludlow, Washington

The gift of living my formative years in the Foreign Service, for which I am eternally grateful, has shaped the meaning of my entire life so far. Who could possibly understand the value of this good fortune? Mining this meaning with those who would most understand is certainly a benefit of reconnecting on a regular basis. Not having this group would be like reading a book and not being able to talk about it with other readers. Even more apt, we are learning directly from the other protagonists in the actual story. Every Cackle provides further insight. In this way, the Foreign Service continues to offer felicity and fulfillment in life, long after our last post.

—John R. Whitman, Chicago, Illinois

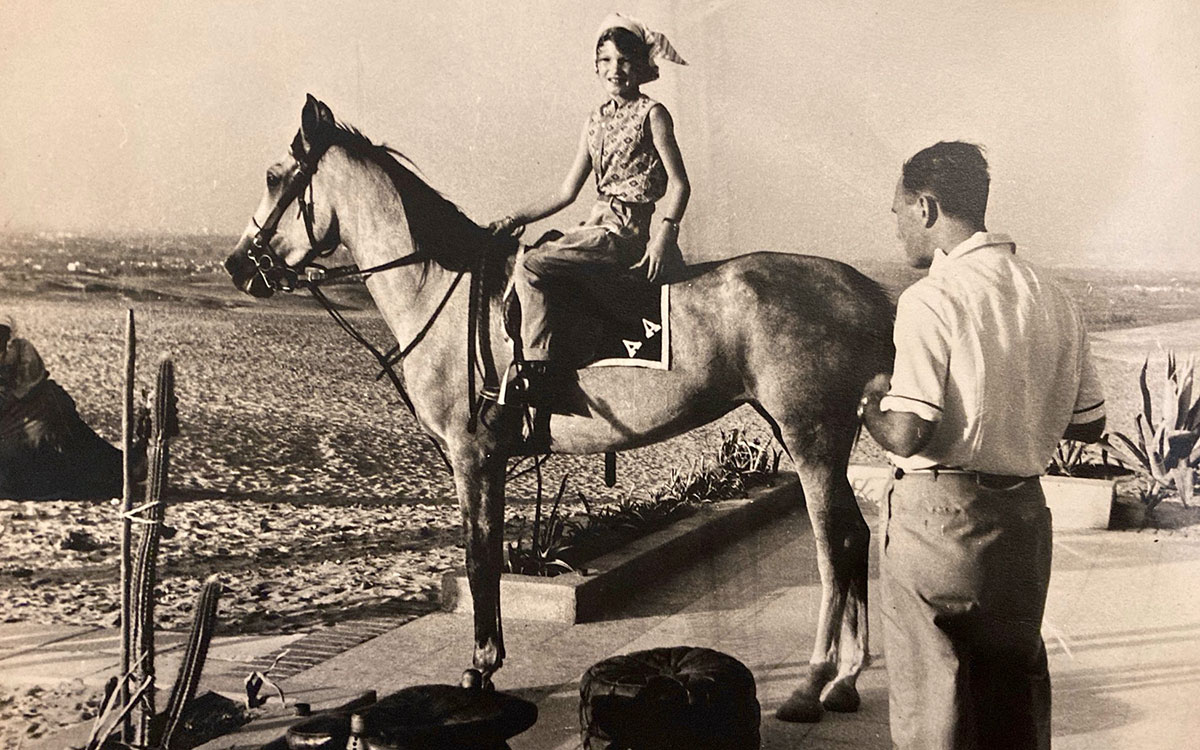

Ruth Whitman, John R. Whitman’s sister, and their father, Roswell H. Whitman. Children rode Arabian horses from the AA Stables adjacent to the pyramids to the tent for social events virtually every weekend.

Courtesy of John R. Whitman

This group emerged spontaneously decades after shared experiences among the children of several nationalities. Does looking back together help affirm our experiences and our way of life as a TCK? Does the account here offer a possible “teachable moment” for both parents and policymakers? What can parents do to better understand the issues of adjustment from the point of view of the children who accompany them overseas?

What does it mean for the aims of the Foreign Service (or any international organization) that the formative experiences of such children can have a lifelong influence on their values, attitudes, and perhaps career choices and voting preferences?

What could such a group offer to current Foreign Service families as suggestions for making the best of a foreign experience for their children? Is there possible value in the reflections of a group long after their retirement years that should be of interest to policymakers and researchers concerned with the image these children leave behind in their host countries?

We are grateful for the opportunity to share our story with the Foreign Service family. Not all of us were affiliated with the U.S. Foreign Service; our common connection is with Cairo American College. And in a larger sense, our fellowship comes from living that extraordinary experience now commonly referred to as “third culture kids.”

When sharing or linking to FSJ articles online, which we welcome and encourage, please be sure to cite the magazine (The Foreign Service Journal) and the month and year of publication. Please check the permissions page for further details.

Read More...

- “A Past Not So Distant” by Amy Cragun Hall, The Foreign Service Journal, November 2019

- “New College, New Culture: Preparing for a Strong First Semester as a Third Culture Kid” by Hannah Morris, The Foreign Service Journal, June 2017

- “The Lure of the ‘Painful Childhood” by Louisa Rogers, The Foreign Service Journal, September 2022