What Does North Korea Want?

It is hard to tell where the recent, unprecedented summitry will lead, but here are some guidelines by which to measure progress.

BY PATRICK McEACHERN

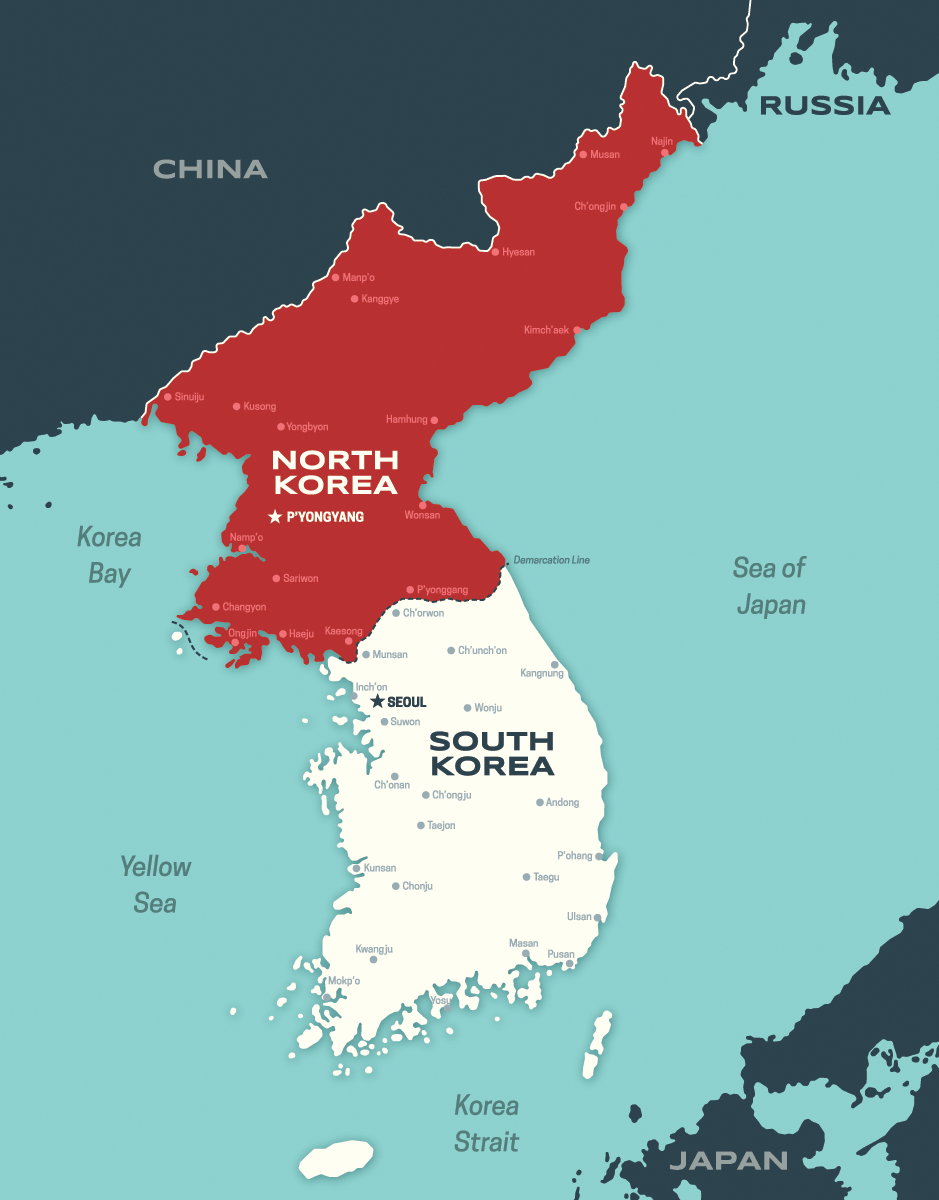

Over the past year, U.S. President Donald Trump and North Korean Chairman Kim Jong Un have held three unprecedented summits—in Singapore in June 2018, in Hanoi in February 2019, and in Panmunjom along the DMZ in June 2019. Where the current process of engagement will lead is difficult to foretell, but the basic contours of the discussion are more predictable.

Each of the three summits sparked a flurry of interest from all walks of life, with press outlets meticulously documenting the personal drama and idiosyncrasies of the leaders and their encounters, including their hotel and transportation selections. The summits also sparked a lively debate in the foreign affairs community over the assumed content of the conversations and wisdom of engaging the North Korean leader at all, so it is useful to bring several basic aspects surrounding the dialogue into clearer focus—namely, North Korea’s fundamental concern for national security and the issue of specific economic sanctions relief.

Diplomats will also appreciate the importance of sequencing in a negotiation, and this article explains the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea’s preferred ordering of transactional discussions as seen from the past three summits. Chairman Kim has highlighted economic benefits through sanctions relief as his early priority, offering some movement on the nuclear issue in exchange. But his government has also noted publicly that later stages of negotiations will require the United States to address North Korea’s own security concerns in the region to elicit more substantial and far-reaching nuclear concessions.

North Korea’s Two Broad Goals

A great deal has been written about what the United States expects from the negotiations. Experts have dissected the term “denuclearization” to expose different interpretations of what the United States seeks—or should seek—and what the North Koreans might be willing to give in return. Some administration advisers demand a complete end not only to the DPRK’s nuclear program but also to its chemical and biological weapons programs and its missile programs. Others add the need to see an end to North Korea’s dire human rights record, conventional threats to its neighbors and a range of illegal activity from smuggling to counterfeiting. Still others present a more targeted agenda of incrementally rolling back North Korea’s nuclear program first before turning to the fuller range of U.S. objectives.

These debates center on foreign policy toward this difficult country on issues vital to U.S. national security rather than on Pyongyang’s own strategic ambitions and near-term goals. In this article I zero in on a basic question: What does North Korea want? In my recent book, North Korea: What Everyone Needs to Know, I tackle this question from a variety of viewpoints that explore the country’s history, society, politics, economics and regional relations. My purpose here, however, is more limited. I focus only on what North Korea wants from the United States in relation to the diplomacy underway.

Kim’s empowering of his diplomats and technical experts to meet their American counterparts is the necessary next step.

It is easy to impute motives to the North Koreans. Few have direct interaction with DPRK leaders, leaving analysts free to speculate on what the Kim Jong Un government seeks. However, Kim has been fairly clear on both his strategic aims and near-term diplomatic asks as a matter of public record. By evaluating what the North Koreans have said repeatedly in public to both their domestic and international audiences, as well as public comments by American officials following the summits, one can identify two broad North Korean goals: national security and specific economic relief. The North Koreans have noted that security is the country’s larger concern, but its near-term demand relates to its economy.

Immediately following the most recent U.S.-DPRK summit in Hanoi, President Donald Trump told reporters that Kim Jong Un “wanted the sanctions lifted in their entirety.” The president’s senior officials, most notably Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, clarified that Kim had wanted an end to those provisions of United Nations Security Council sanctions that applied to general economic activity. The administration decided in Hanoi that North Korea’s offer related to its Yongbyon nuclear complex was insufficient to merit this level of sanctions relief.

The distinction between all sanctions and the specific sanctions relief Kim sought, as well as the value of nuclear concessions focused only on Yongbyon, require some explanation.

Near-term Demand: Targeted Sanctions Relief

Resource List

Patrick McEachern, North Korea: What Everyone Needs to Know (Oxford University Press, 2019)

Anna Fifield, The Great Successor: The Divinely Perfect Destiny of Brilliant Comrade Kim Jong Un (Public Affairs, 2019)

Sandra Fahy, Dying for Rights: Putting North Korea’s Human Rights Abuses on the Record (Columbia University Press, 2019)

Van Jackson, On the Brink: Trump, Kim, and the Threat of Nuclear War (Cambridge University Press, 2018)

Stephan Haggard and Marcus Noland, Hard Target: Sanctions, Inducements, and the Case of North Korea (Stanford University Press, 2017)

Byung-Yeon Kim, Unveiling the North Korean Economy: Collapse and Transition (Cambridge University Press, 2017)

Andrei Lankov, The Real North Korea: Life and Politics in the Failed Stalinist Utopia (Oxford University Press, 2013)

Victor Cha, The Impossible State: North Korea, Past and Future (Ecco Press, 2012)

Justin Hastings, A Most Enterprising Country: North Korea in the Global Economy (Cornell University Press, 2016)

The United States has imposed sanctions on North Korea unilaterally since the country’s inception, but the U.N. Security Council sanctions that Chairman Kim referenced are much more recent. His grandfather, Kim Il Sung, was instrumental in declaring the establishment of the DPRK in 1948. Two years later, he invaded U.S.-backed South Korea, initiating the Korean War. Not surprisingly, the U.S. government did not look fondly on American companies doing business with the enemy, and North Korea’s invasion triggered sanctions through the Trading with the Enemy Act.

Cold War–era politics brought the addition of sanctions related to North Korea’s status as a communist and socialist state. Its egregious human rights record and its history of state-sanctioned drug smuggling and terrorism, counterfeiting of U.S. currency, proliferation of missile and nuclear technology, and a host of other offenses have led North Korea to be sanctioned under multiple overlapping authorities. There is no near-term prospect for relief of U.S. sanctions that could spur bilateral trade, and North Korea did not ask for this in Hanoi.

Kim Jong Un’s sanctions relief demand was much more targeted and has a shorter history. After North Korea’s first nuclear test in 2006, the U.N. Security Council began issuing a series of resolutions with sharper and sharper teeth. During the first decade after the inaugural nuclear test, these multilateral sanctions focused on denying North Korea the tools to build a nuclear weapons program and moved into restrictions on luxury goods for the regime’s elite. Previous North Korean claims that its nuclear infrastructure was intended for nuclear energy production had convinced few after the first nuclear crisis in the early 1990s, but North Korea’s public demonstration of its weapons ambitions with its first nuclear test allowed all veto-wielding Security Council members—including Russia and China—to condemn and sanction the program.

Nonetheless, North Korean nuclear tests and long-range missile launches continued. More countries, most notably Japan and the Republic of Korea, restricted their own trade with North Korea further in the years after 2006. Even as the fiercely nationalistic Kim regime continued to articulate a desire for self-reliance and built an autarchic economy to support it, the regime became increasingly reliant for foreign goods and economic inputs like oil on a single neighbor: China. China grew to account for more than 90 percent of North Korean trade; yet even Beijing could not rein in Pyongyang on the nuclear issue, and Sino–North Korean relations deteriorated.

In 2016, Beijing assented to put greater pressure on North Korea. Following the country’s fifth nuclear test, China voted in favor of new U.N. Security Council sanctions that did not simply seek to limit North Korea’s ability to import nuclear-related material or apply restrictions on North Korea’s elite like travel bans or luxury goods import prohibitions. China agreed to preclude what would otherwise be considered legitimate trade in an economically significant sector: minerals and coal.

Offer Related to Yongbyon

North Korea could not export coal and other minerals, which were critical components of its foreign currency– earning exports. Subsequent resolutions would expand restrictions on North Korean trade and foreign currency–earning activities. The U.N. Security Council banner is important to urge other countries to cut off sanctioned trade with North Korea, but the most important element was Chinese enforcement. As North Korea’s dominant economic partner that shares a land border, Beijing could then and can now undercut the sanctions’ pressure entirely. However, the Chinese have largely held firm, which has proven pivotal to preserving American leverage in nuclear discussions with the North Koreans.

Public comments by senior administration officials suggest that Kim Jong Un’s opening demand in Hanoi sought to roll back this series of sanctions in place since 2016. This is a targeted and transactional request that would not transform North Korea economically. Removing the last three years’ worth of heightened sanctions would return North Korea to its early 2016 status. It would not allow foreign investment to flow into North Korea; nor would it recast the country’s economy or external relations.

In exchange, as Secretary Pompeo explained after the Hanoi summit, North Korea offered limitations on its Yongbyon nuclear complex. Yongbyon is North Korea’s most famous nuclear site. Foreign Service Journal readers are likely familiar with Yongbyon’s name because it has been the centerpiece of North Korea crisis diplomacy for more than a quarter-century. However, it is no longer North Korea’s most significant fissile material production facility. Yongbyon’s plutonium reactor is limited to producing about a bomb’s worth of plutonium each year, and its uranium enrichment facility is relatively small.

We have known from public sources for almost a decade that at least one other, much larger uranium enrichment plant is located elsewhere in the country. North Korea’s enrichment program outside Yongbyon also has the capacity for substantial growth in its production capability, while Yongbyon is relatively static. As such, it is important but not the prize it once was. Reasonable people can disagree on whether it was in the U.S. interest to accept North Korea’s offer, but Kim did not seem to present a second offer to come off this initial demand. The Hanoi summit showed Kim’s near-term ambition to achieve partial sanctions relief in exchange for limited nuclear dismantlement, but he ultimately failed to achieve it.

Strategic Aim: National Security

North Korean leaders have stressed that the country’s nuclear program is targeted at what Pyongyang views as the American existential threat to its existence. North Korea learned from the 1991 Persian Gulf War that numerical superiority of military personnel would not prevail against superior American military technology. They likewise note that the 2003 Iraq War showed them that only an actual nuclear weapons capability can deter the conventionally superior American military from pursuing regime change.

More recently, North Korean state media has stated explicitly that sanctions relief is the near-term ask, but national security is the ultimate goal. From North Korea’s perspective, nuclear weapons do a good job of deterring a more technologically advanced military’s ability to oust the Kim regime. For more substantial North Korean denuclearization concessions beyond the initial offer, the United States would have to go beyond sanctions relief and address North Korea’s security fears in a tangible way.

Amid the summit diplomacy the Trump administration has made a significant concession to ease the country’s security fears. North Korea has long complained about the semiannual U.S.–South Korea military exercises, which they see as a security threat. The United States suspended these exercises twice since the first U.S.-DPRK summit in Singapore, though the administration resumed the exercises in August. The North Koreans must utilize scarce resources like fuel to mobilize forces while heightened U.S. military assets and personnel are in the region for the exercises. If the United States were to launch a preemptive strike on North Korea, they reason, a military exercise would be the perfect cover to plus-up for an invasion.

The U.N. Security Council banner is important to urge other countries to cut off sanctioned trade with North Korea, but the most important element was Chinese enforcement.

The United States and the ROK have repeatedly noted that the exercises are defensive, meaning they allow the two militaries to drill to respond more effectively to possible North Korean provocations or invasion. Suspending the exercises limits U.S.-ROK military readiness. It is not a cost-free move, but alternative training arrangements can mitigate some of the downside risk for the United States and South Korea. North Korea had refrained from long-range ballistic missile flight tests and nuclear testing amid the exercise freeze, but predictably expanded shorter-range ballistic missile launches after the exercises resumed. The pause to create room for diplomacy had not produced more tangible results in the intervening months.

While North Korea finds the U.S. military presence on the Korean Peninsula threatening, it is less clear exactly what it would require of the United States to feel secure enough to permanently dismantle the nuclear program. Pyongyang has called for a peace treaty to end the Korean War. Declassified records from Kim Il Sung’s conversations with his socialist counterparts as late as the 1970s show the North Koreans understood a peace treaty as a pretext to end the permanent stationing of U.S. troops in South Korea.

More recent Track 2 engagements (nongovernmental discussions) provide contradictory interpretations of what Kim Jong Un today may seek from a peace arrangement, and it is by no means clear whether he has envisioned a neatly laid out endgame. However, North Korea’s demand regarding military exercises during the U.S.-DPRK summitry shows that Kim Jong Un considers that chipping away at U.S. Forces Korea’s capabilities in exchange for incremental limitations on its own nuclear capabilities is part of the equation.

While it is possible to imagine Kim Jong Un wanting to achieve what his father and grandfather never could—removal of all foreign troops from Korean soil—it remains to be seen whether such an arrangement would be ultimately achievable or desirable for U.S. interests in Korea and the region. In the context of long-standing U.S.-DPRK distrust, Kim Jong Un has not prioritized a transformed relationship with the United States where it counts most, among his top diplomatic demands. President Trump has fashioned himself a different type of American leader, so one may reason that Pyongyang would be naturally suspicious that any deal with him may not survive into the following administration—or his own second term.

Where Do We Go from Here?

Kim’s offers to date suggest he is focused first and foremost on a transactional deal to reduce immediate economic pain and make incremental security advances. In general terms, his demands are not that much different from those articulated by his father since the early 1990s, and President Trump’s pursuit of a denuclearized North Korea is roughly similar to the objective of his last three predecessors. Technological advancement in North Korea’s nuclear program and reordering of priorities have updated each side’s top asks and suggested a different sequencing for negotiations, but the basic outlines of a deal to address each side’s core demands have been present and explored in multiple rounds of high-stakes diplomacy for decades without completely resolving the fundamental issues at hand. This has led to understandable skepticism that any deal is possible and begs the question of what is new this time.

The main difference between the latest diplomacy and previous rounds is the personal involvement of the two leaders. There is no precedent for U.S.-DPRK summitry prior to the Trump-Kim meetings, and it has created new opportunities and challenges. Contrary to prior rounds of diplomacy, there was no ambiguity about whether the Singapore Declaration reflected the position of the top leaders in both systems. At the same time, however, Chairman Kim also did not unleash his negotiators to lay out a series of quid-pro-quos that would provide a roadmap to a phased, transactional deal. He preferred instead to try to engage President Trump directly, which led to another two summits without an implementable agreement. It appears Kim may have figured out that this tactical approach will not produce the type of technical agreement needed to address his concerns.

The next step to look for is far less dramatic than the world has seen over the past eighteen months. Kim’s empowering of his diplomats and technical experts to meet their American counterparts is the necessary next step to tee up a deal on each side’s core demands that the leaders could endorse. Yet another dramatic summit may do more to capture the headlines, but it would almost certainly be for naught. The best hope for making another summit productive is for teams of technical experts on both sides to sit down to iron out a phased approach to denuclearization, sanctions relief and a structured response to North Korea’s security concerns. That step alone would be far more newsworthy.

U.S.–North Korea Nuclear Negotiations: A Timeline

1985 • North Korea joins the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) under Soviet pressure.

1991 • President George H.W. Bush announces that the United States has removed all nuclear weapons from South Korea, a long-held North Korean demand to agree to denuclearize.

1992 • North Korea and South Korea agree to denuclearize the peninsula.

1993 • North Korea threatens to withdraw from the NPT, but suspends withdrawal following talks with U.S. diplomats in New York.

1994 • The United States and North Korea sign the Agreed Framework, freezing Pyongyang’s nuclear program.

1999 • North Korea suspends testing of long-range missiles in exchange for U.S. easing of economic sanctions for the first time since the beginning of the Korean War in 1950.

2000 • June: South Korean President Kim Dae-jung meets with DPRK President Kim Jong Il in Pyongyang, the first summit between Korean leaders in five decades.

2000 • October: North Korean General Jo Myong Rok meets with President Bill Clinton in Washington, and Secretary of State Madeleine Albright travels to Pyongyang to discuss the country’s ballistic missile program.

2002 • President George W. Bush challenges North Korea’s compliance with the Agreed Framework and characterizes the country as part of an “axis of evil” with Iraq and Iran in the State of the Union Address.

2002-2003 • The Agreed Framework breaks down as the United States claims North Korea admitted to running a secret uranium-enrichment program, and North Korea denies it. North Korea withdraws from the NPT.

2003 • Six-Party Talks (South and North Korea, China, Japan, Russia and the United States) open in August.

2005 • Sept. 19: Six-Party Talks produce a joint declaration in which North Korea commits to abandon its pursuit of nuclear weapons and implement International Atomic Energy Agency safeguards and the terms of the NPT in exchange for a U.S. assertion that it has no intention of attacking North Korea.

2006 • Oct. 9: North Korea conducts its first nuclear test, which prompts U.N. Security Council condemnations and trade sanctions. A low yield from the test leaves question whether North Korea could successfully detonate a nuclear device.

2007 • The six parties agree to two action plans in February and October in which North Korea commits to halting operations at Yongbyon and then starting to disable the reactor in exchange for a series of political, economic and energy concessions from the United States and its allies.

2008 • Pyongyang declares 15 nuclear sites and 30 kilograms of plutonium in June; in exchange, President George W. Bush rescinds some trade restrictions, waives some sanctions and announces a plan to remove North Korea from the list of state sponsors of terrorism. The State Department announces preliminary agreement with North Korea on verification, but discussions break down by December.

2009 • Pyongyang rebuffs Obama administration efforts to revive the Six-Party Talks, ejects monitors from its nuclear facilities and tests a second nuclear device. That test is successful and erases ambiguity about whether North Korea had fully crossed the nuclear threshold. First bilateral meetings take place in December.

2011 • Kim Jong Un takes power in Pyongyang after the death of his father, Kim Jong Il.

2012 • North Korean nuclear operations are briefly suspended in exchange for a pledge of tons of food aid after months of negotiations. The deal breaks down within weeks when North Korea launches a long-range rocket.

2013-2014 • Diplomacy stalls as Washington and its allies ratchet up sanctions. North Korea carries out nuclear tests and increases testing of ballistic missiles.

2017 • President Donald Trump redesignates North Korea a state sponsor of terrorism after Pyongyang conducts its sixth nuclear test. Pyongyang boasts it can reach U.S. soil with nuclear-tipped intercontinental ballistic missiles, and the Trump administration threatens a military strike.

2018 • March: South Korea’s national security adviser announces in Washington that President Trump has accepted an invitation to meet Kim Jong Un in Pyongyang. This follows diplomatic overtures between North and South spurred by the Winter Olympic Games, hosted by South Korea.

2018 • June 12: Kim and Trump hold a historic meeting in Singapore, issuing a joint declaration pledging to pursue lasting peace and complete denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula.

2019 • Feb. 27-28: Second Trump-Kim summit ends early without an agreement when leaders disagree over the terms of a deal, including sanctions relief and denuclearization.

2019 • June 30: President Trump becomes the first sitting U.S. president to set foot in North Korea when he steps across the border at Panmunjom to meet Kim; the two agree to restart stalled nuclear negotiations.

Sources: Council on Foreign Relations, “North Korean Nuclear Negotiations, 1985–2019” and Arms Control Association, “Chronology of U.S.-North Korean Nuclear and Missile Diplomacy.”