When USAID Disappears

America’s first line of defense—the professional, nonpartisan U.S. Foreign Service—is under threat. Career diplomats and development experts are being fired or sidelined, and the value of public service questioned and politicized.

AFSA launched the Service Disrupted public awareness campaign in May to help illustrate the work of the Foreign Service and why it matters. We’ve been collecting testimonials from members to help illustrate the critical work of diplomacy and development and what is lost when the work is halted.

We published the first set of Service Disrupted stories in the April-May FSJ, “Lives Upended: The Impact of USAID’s Dismantling on Those Who Serve." The second set, “What We’ve Lost: Firsthand Accounts from the Field,” was published in the June FSJ. Here we share the third installment. The stories have been lightly edited for clarity. Two are printed anonymously, but the authors are known to us.

Please consider sharing your own story or that of a colleague. What is important about the work you do, and what will be (or has been) lost without you in the field? What does America lose as the result of your program and/or position being shuttered? What do you want Americans to better understand about the work of diplomacy and development and why it matters?

We will continue to share your stories in the Journal and on AFSA social media channels. Send submissions of up to 500 words to us at humans-of-fs@afsa.org.

—The Editors

USAID IS VANISHING

BY JIM BEVER

For almost eight decades, USAID employees and other professionals in international development worked to implement the vision of General George Marshall, President Harry S Truman, and every U.S. president since, fostering freedom and stability throughout the world. But in the first 100 days of the second Trump administration this proven tool of U.S. foreign policy was targeted for almost complete elimination—without a national security strategy to explain or justify it.

The Marshall Plan

President John F. Kennedy delivers remarks at the White House to a group of USAID mission directors on June 8, 1962, shortly after the agency was established. He told them, “There will not be farewell parades to you as you leave or parades when you come back.”

USAID

After World War II ended with the defeat of Nazism, President Truman’s Secretary of State, former five-star General George C. Marshall, initiated the European Recovery Act—now remembered as the Marshall Plan. As the prospect of yet another war with the Soviets and the specter of communism’s spread grew in southern Europe, Marshall laid out the Truman administration’s vision to protect the continent, saying the plan would be directed “against hunger, poverty, desperation, and chaos. Its purpose should be the revival of a working economy in the world so as to permit the emergence of political and social conditions in which free institutions can exist.” Marshall concluded: “The only way human beings can win a war is to prevent it.”

The Marshall Plan was not a government handout. As Foreign Service Officer (ret.) Steven Hendrix wrote in the Diplomatic Courier: “It was a geopolitical strategy backed by infrastructure, know–how, and American pragmatism. And it worked. It established a model: development assistance could be both altruistic and in the national interest.”

As more young nations broke free of their colonial masters over the ensuing 15 years (India, Pakistan, Egypt, Ghana, Indonesia), the Cold War competition for hearts and minds in these new struggling republics grew, and various U.S. government implementing entities (such as USAID’s predecessor, the International Cooperation Administration) worked to meet the demand for assistance.

In 1961, in response to the increasing needs of people overseas and with the desire to ensure newly created countries would stay on the U.S. side of the Cold War, President John F. Kennedy pulled together disparate assistance programs to establish USAID. In his inaugural address he stated: “To those people in the huts and villages of half the globe ... we pledge our best efforts to help them help themselves.” Kennedy boldly challenged Americans in that inaugural address more than three generations ago to fight “against the common enemies of man: tyranny, poverty, disease and war.” He continued with one of his most famous lines: “And so, my fellow Americans: ask not what your country can do for you—ask what you can do for your country.”

That last line was a clarion call to Americans, especially its baby-boom generation. Thousands of Americans joined the Peace Corps, usually for two years, and thousands also joined the new Agency for International Development, living full careers serving the American people overseas, often in dangerous and unstable countries.

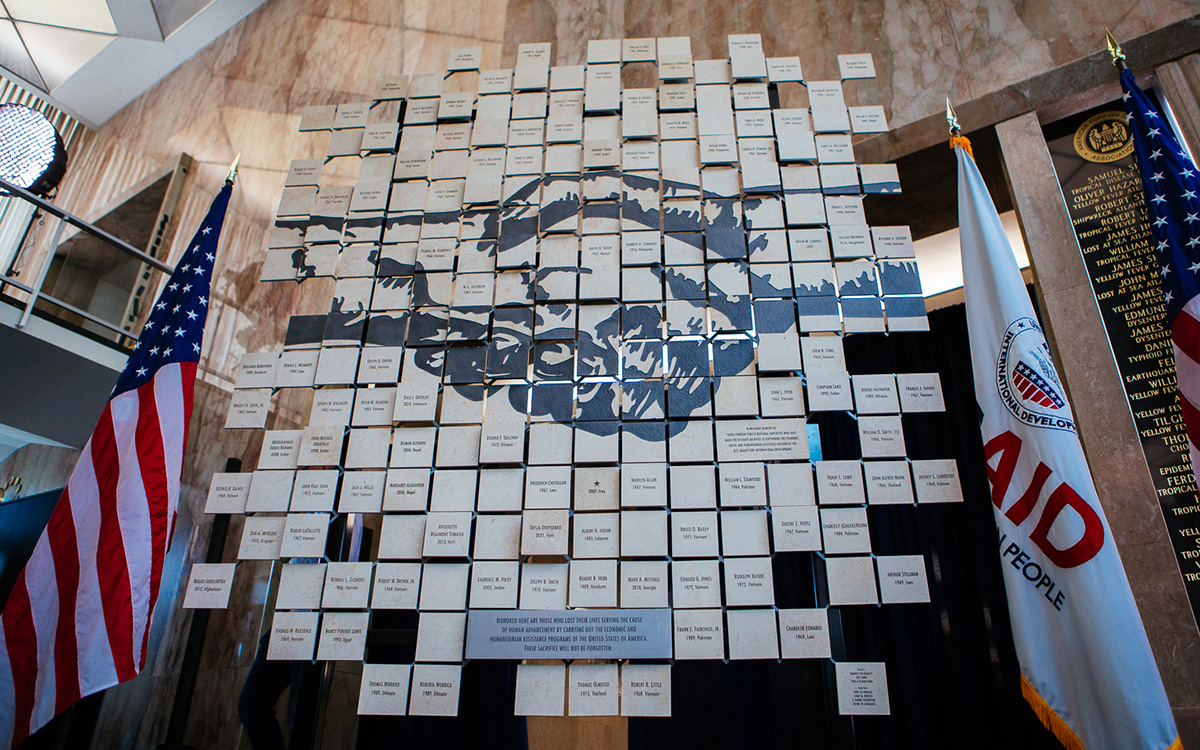

As the Vietnam War expanded, so too did USAID. At its peak, the agency had thousands of Foreign Service officers in Vietnam alone. Some did not return home: The Wall of Honor that until recently stood at the entrance to USAID headquarters in Washington, D.C., offers tribute to the more than 100 AID FSOs (and countless more Foreign Service Nationals) who died in the line of duty, half of them in Vietnam.

That famous Kennedy line was followed immediately by one not as famous, but equally important: “My fellow citizens of the world: ask not what America will do for you, but what together we can do for the freedom of man.” This idea—that we are all in this challenge together—is symbolized by the famous handshake at the center of AID’s original logo, based on George C. Marshall’s own hand-drawing and emphasizing the partnership implied.

On Oct. 7, 2016, USAID members and service members from Joint Task Force Matthew delivered relief supplies to areas affected by Hurricane Matthew to Jeremie, Haiti. JTF Matthew delivered more than 10,000 pounds of supplies on its first day of operations.

Capt. Tyler Hopkins / U.S. Navy

Programmatic Carnage

And now here we are in 2025. By the end of this summer, almost all of the more than 8,000 USAID staff—Foreign Service, Civil Service, and Foreign Service Nationals—are set to be fired, subject to reductions in force (RIFs). While the administration says it plans to at least retain funding for food aid, transition initiatives, and lethal infectious disease prevention and its directly related health sector strengthening, the balance of foreign assistance funding for what is known as “development assistance” is being whited out.

Some 200 single-spaced pages list tens of billions of dollars of cuts to such development assistance, eliminating technical assistance, policy reform, institutional strengthening programs, training, equipment, matériel, and infrastructure funding in 100 developing countries. These investments in development that took person-centuries of professional effort—and taxpayer money already spent or committed to scope out, compete, and implement—have been torn asunder at the start or even in midstream.

In the aftermath of this programmatic carnage, the United States and the world have both lost. We all lose.

Five-time USAID Mission Director Jonathan Addleton wrote recently in the Pakistan daily newspaper The Nation: “As a former US Ambassador, it is difficult to imagine a world in which development assistance is not part of the diplomatic toolkit available for engaging with other countries … as a development partnership setting the stage for exponential economic growth that ultimately benefits both countries.”

Yet that is the world in which we are all now living.

Former CIA Officer Brian O’Neill pointed to this “strategic inversion” in an op-ed in the April 29, 2025, Atlanta Journal-Constitution, writing that our adversaries are “re-calibrating based on our weakness” and “reallocating resources and rethinking their posture.”

The damage to our country’s safety and security is impossible to overstate. Senator Mark Kelly (D-Ariz.) discussed the importance of USAID in an April 28, 2025, interview in The New York Times, saying: “You can spend a little bit of money on trying to solve these problems, like famine in places like Sudan or Afghanistan or other countries, or you can buy more bullets. There’s somebody that might be complaining about foreign aid today, and tomorrow, or five years from now, they’re sending their kid overseas to fight in a war that wouldn’t have otherwise happened.”

As of this writing, President Trump has no new National Security Strategy to explain to Congress and to the American people the rationale for his destruction of U.S. foreign assistance. The most recent National Security Strategy was published by President Joe Biden in October 2022. Americans need to know: What national interests are at play? What are the threats? The opportunities? The risks and assumptions? Are the resources proposed adequate? What are the trade-offs?

In the Balance

The president hasn’t zeroed out aid to prevent lethal infectious disease from hitting our own people. But let’s look at the balance of foreign assistance beyond that. There appears to be no commitment to sustain the incredible improvements—due to USAID’s long-term interventions—in the following areas:

- reducing infant mortality, child mortality, maternal mortality in childbirth; and deaths and lifelong injury from malnutrition, malaria, tuberculosis, diarrheal disease, and polio;

- preventing and mitigating conflicts that lead to out-migration;

- providing rural development and agricultural technical assistance to prevent crop disease or develop new crop varieties in the face of world food price shocks, war-induced scarcity, and weather changes that lead to famine and out-migration;

- protecting the environment: reducing industrial, air, and water pollution; protecting coastal fisheries, wildlife, and minerals resources in the face of exploitation that contributes to poverty, dislocation, and out-migration;

- offering technical or infrastructure assistance for energy development, efficiency, and diversification of supply, the lack of which leads to instability in aspiring economies;

- providing technical and policy assistance for national macroeconomic, fiscal, financial, and trade reforms, private enterprise development, business policy reform, and sanctity of contract—all of which benefit U.S. companies, aid job growth, and enhance stability;

- providing technical or infrastructure assistance to education, from pre-K to graduate level to help create self-reliance and sustainability (USAID’s work in this sector has been a success from the beginning—for example, in the early 1960s in India, the agency helped more than 10,000 students to earn PhDs and master’s degrees, changing the face of India today); and

- supporting democracy and accountable, representative governance—not just free and fair elections support but party strengthening, women in government, and access to justice.

The USAID memorial wall was moved next to the State Department Memorial Plaques ahead of the Foreign Service Day plaque ceremony on May 2, 2025.

AFSA / Joaquin Sosa

A Proven Capability in Jeopardy

Finally, it’s not just USAID’s systems and practices that have assured accountability for both spending and results. It is the development professionals, the people of USAID, who matter the most. In addition to RIF’ing almost 2,000 Civil Service staff at HQ, we are pushing out almost all of the 2,000 USAID FSOs. These FSOs have advanced degrees in professional fields of international development and decades of experience serving exclusively in the developing world—often in conflict zones such as Afghanistan, Iraq, Sudan, Yemen, Somalia, Lebanon, and West Bank/Gaza. These experienced officers serve on the ambassador’s Country Team at every post, interact with host governments, businesses, and civil society at all levels, and support congressional delegations. Equally in danger of being RIF’ed are the 4,500 Foreign Service National staff, most of them equally technically skilled, seasoned professionals with decades of experience at our embassies overseas.

The administration’s 2026 budget request for USAID is only 15 percent of the previous budget, eliminating most programs and staff. Those of us who have served our country through careers at USAID have been blessed to make a positive difference in the world while protecting and enhancing America’s security, prosperity, and values.

Absent a congressional miracle, we’re gone.

When Engineers Stop Working

As a USAID Foreign Service engineer, I’ve had the unique privilege of supporting infrastructure projects and programs that improve lives, advance local economies, and embody American generosity. My work has ranged from building latrines in Angola and modernizing health facilities in Namibia to establishing an infrastructure delivery team within Angola’s Ministry of Transit. What ties it all together is a deep commitment to working alongside our stakeholders—not just to build things but to build rapport and long-term partnerships.

When American engineers are in the field, we’re not just managing projects, we’re mitigating risks, promoting U.S. quality, and ensuring that every taxpayer dollar is spent wisely. We hold contractors accountable. We mentor local engineers. We bridge the gap between infrastructure and diplomacy to deliver results that matter. Our presence is irreplaceable.

Since the suspension of U.S. foreign assistance, dismantling of USAID, and the subsequent elimination of its engineering staff, we’ve already seen critical programs delayed, downsized, or completely halted. Clinics in South Africa have been shuttered, high schools in Mozambique left unfinished, and partially repaired municipal water systems in Jordan have been abandoned. These open pits and shells of buildings still bear USAID branding and the American flag. We are literally advertising failure while undermining the very goals of U.S. assistance.

This loss affects American credibility. When we deliver smart infrastructure, we show up as a reliable partner. When we don’t, we leave a vacuum that other global powers are eager to fill. Engineering is quiet diplomacy, and our tools are trust, quality, and results.

I want Americans to know that the work we do in USAID engineering is not just technical, it’s strategic. It’s nation-building in the best sense: helping build resilient communities while reinforcing the U.S. commitment to shared prosperity and global stability. Losing that presence isn’t just a staffing or resource issue, it’s a retreat from our leadership role in the world.

—USAID FSO

Build Anyway

I am a USAID Foreign Service officer from New York and have served for 13 years in Ecuador, Haiti, India, and Washington, D.C. I managed people, budgets, and programs. I built partnerships with local governments, large and small businesses, communities, and other donors. I wrote memos, articles, and reports so that Washington, the ambassador, our local partners, Congress, and the American people knew what we were doing and why. Always working as a team, we sought to solve problems like malnutrition and air pollution, illegal poaching, lack of electricity and water, or the difficulty of getting a loan to start a business.

We attacked these issues because we believed that all people should be able to attain a decent standard of living. In a world with billionaires and unthinkable luxury for the very few, is access to clean drinking water or safe classrooms an unreasonable hope?

I recently worked on a large contract supporting trade and investment across Africa. The abrupt halt of foreign assistance and termination of the contract meant that the small African businesses we’d agreed to invest in were unable to complete their expansion plans and were left with inputs they could no longer afford. These are mortal blows for entrepreneurs operating in highly challenging environments. Our goal was to build the economic base of multiple countries so that they no longer required outside assistance. This path to self-reliance is a longheld, bipartisan development approach that we are suddenly undermining like secret saboteurs.

In an earlier assignment, I worked to increase regional cooperation among the countries of South Asia (including India, Bangladesh, Nepal, and Bhutan) through energy trade and infrastructure. Bangladesh has long been one of the poorest countries in the world and has witnessed explosions of violent extremism in the recent past. Bangladesh is not only on the verge of “graduating” to a lower-middle-income country (a huge development success), it is also undergoing a democratic transition.

USAID partnered with Bangladesh for decades to support democratic institutions and improve working conditions within garment factories. But now, at this moment of immense change, when transformation for good is so possible but the potential for a collapse into factionalism and corruption hangs like a sword over the future, USAID’s support has suddenly disappeared as the U.S. announced major tariffs on Bangladesh’s leading export industry. I am reminded of Mother Teresa’s observation: What you spend years building someone can destroy overnight. Her conclusion? Build anyway.

In USAID’s Foreign Service I worked for the American people, with resources provided by the American people. Foreign assistance asks our country to invest in others so that we can reap the benefits of a more stable and prosperous world. Without it, we will need to increase spending on defense, immigration, pandemics, and disaster response. We will face a devastating human toll from abandoning the generosity and compassion we once championed.

USAID’s destruction was quick and deceptively easy. The rebuilding, which is sure to come as the pendulum swings, will be long, arduous, and costly. Build anyway.

—USAID FSO

When sharing or linking to FSJ articles online, which we welcome and encourage, please be sure to cite the magazine (The Foreign Service Journal) and the month and year of publication. Please check the permissions page for further details.