“Wherever the Wind Takes Us”—Poor Air Quality and Long-Term Foreign Service

One ESTH officer with access to an air quality monitor set out to discover how poor air quality at some posts might affect fellow Foreign Service officers and their family members.

BY MICHELLE ZJHRA WITH CLAIRE KIDWELL AND LINDA GEISER

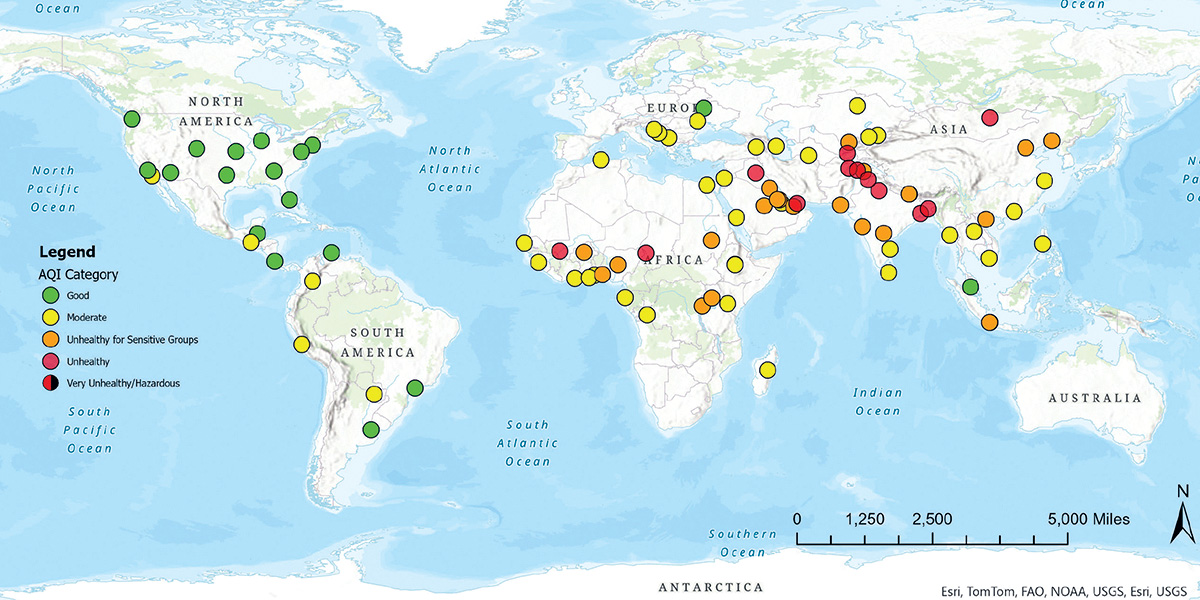

Average annual PM2.5 levels in major U.S. cities and U.S. embassies measured by EPA-certified BAMs from 2021 to 2023. Colors reflect the pre-2024 EPA Air Quality Index classes that relate PM2.5 levels to evidence-based health impacts. U.S. cities include the greater metropolitan areas of Atlanta, Chicago, Dallas–Fort Worth, Denver, Kansas City, Los Angeles, Miami, New York, Phoenix, Seattle, and Washington, D.C. Data were retrieved by the authors from the EPA for U.S. embassies and EPA’s Air Quality System for U.S. cities. Map should not be used to assess compliance with U.S. air quality standards.

I was having trouble breathing as I left the embassy in Antananarivo, Madagascar, to return home from work. This was not an uncommon occurrence—the exhaust from cars mixing with cookstove smoke during peak commuting times often left the air clogged with fumes. And it was not the first time I experienced this during an overseas posting. In more than a decade of service with the Department of State, I have worked in countries with even worse air pollution than Antananarivo, where the very air itself takes on a pallid yellow hue. But at this moment, as my lungs struggled in the evening air, I started to wonder what the effect of breathing bad air over long periods of time had on me, my fellow Foreign Service members, and our families.

World Health Organization (WHO) data show that most people worldwide breathe air that “exceeds WHO guideline limits and contains high levels of pollutants, with low- and middle-income countries suffering from the highest exposures.” These pollutants are a major public health concern and include fine particulate matter, carbon monoxide, ozone, nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide, lead, and a chemical soup of volatile organic compounds, metals, and partial combustion products. Both outdoor and indoor air pollution cause respiratory and other high morbidity/high mortality diseases.

While we as members of the Foreign Service anticipate some risk associated with our positions, I worried what prolonged exposure was doing to our long-term health.

Getting the Data

With our PAM air quality monitor tucked inside a car-topper, we measured five air pollutants and temperature every 10 seconds. Our phones connected to the monitor by Bluetooth, displaying and recording data in real time.

We detected 41 ug/m3 of PM2.5, unhealthy for sensitive groups, from the truck ahead. People in Madagascar, especially those walking, cycling, shopping, or selling at open markets and storefronts near busy roads, are routinely exposed to poor air quality.

Linda Geiser / U.S. Forest Service

Serving as the environment, science, technology, and health (ESTH) officer in Antananarivo, I was fortunate to have access to an air quality monitor located within the embassy compound. This beta-attenuation monitor (BAM) is certified by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and measures levels of fine particulates in the air under 2.5 micrometers in diameter (PM2.5). PM2.5 levels are associated with health risks such as acute respiratory illnesses, asthma and other lung diseases, cardiovascular disease, and early mortality.

The BAM takes a reading every hour on the hour, but it only represents the air on the embassy compound, not the rest of Antananarivo or the rest of the country. I realized that if we could procure air quality measurements elsewhere in Madagascar, we would understand how air quality varies from place to place and learn where and how often Foreign Service members on the island were being exposed to poor air quality.

I could not do this alone. In 2022 I used a small grant from the State Department Bureau of Oceans and International Environmental and Scientific Affairs (OES) to invite air quality expert Linda Geiser from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Forest Service to join local researchers on a tour of the country, gathering air quality data in major cities, villages, and nature reserves. We drove around the island with a 2BTechnologies Personal Air Quality Monitor (PAM) mounted on top of our car, taking readings as we traveled through bustling rural towns. We carried it by hand along foot trails in lush nature reserves and into buildings during indoor gatherings.

What we found was not reassuring. During the dry season, a layer of haze covers the country, including within Madagascar’s major nature reserves. In Antananarivo, three years of BAM monitoring demonstrated that average daily air quality was best during the wet season and worst during the dry season. On an hourly basis, air quality was generally poorest in the early morning and late afternoon, coinciding with primary commuting times, when many embassy workers are ferrying kids to and from school, getting groceries, and bicycling or running between home and work. I wondered if there was a way to anticipate what the air would be like for the day.

I was discouraged to learn that although our BAM produced air quality data that is updated hourly on our embassy’s web page, few people seemed aware of it. When a day’s data is averaged, even during a “good” air day—that is, a day that meets the U.S. EPA 24-hour standard for PM2.5—the air quality is usually moderate to unhealthy during peak commute times. My concern increased when I determined that the State Department lacks standardized guidelines for its officers abroad to reduce their exposure to air pollution and protect themselves from unhealthy air. In discussing my data and conclusions with my colleagues at the embassy, one question continued to come up: What could we do about it?

Raising Awareness

In the United States, we have laws and regulations to protect air quality and communication tools to build air quality awareness among U.S. citizens. The Air Quality Index (AQI), initiated in 1976 by the EPA, was implemented to communicate air quality conditions and recommended precautions for citizens in plain language. The AQI divides PM2.5 readings into categories: good, moderate, unhealthy for sensitive groups, unhealthy, and hazardous. While WHO standards are stricter than the ones we keep in the U.S., in 2024 the EPA strengthened the annual PM2.5 standard, presenting an opportunity for the State Department to strengthen and standardize its own air quality policies in tandem. The department could use EPA standards as a framework for acknowledging air quality health effects on Foreign Service members and their families who serve overseas, particularly those serving in moderate-to-poor air quality countries over the course of a career. Local BAM data can also be used to provide a ballpark assessment of increased risk of mortality from all causes, cardiopulmonary diseases, and lung cancer.

By mapping annual average PM2.5 data at U.S. embassy BAMs from 2021 to 2023, one can readily see that the worst air pollution is occurring in parts of Africa, the Middle East, and Asia.

By mapping annual average PM2.5 data at U.S. embassy BAMs from 2021 to 2023, one can readily see that the worst air pollution is occurring in parts of Africa, the Middle East, and Asia. Average air quality at U.S. posts in these areas is moderate to unhealthy depending on the city, whereas average air quality at posts in the Americas and Europe ranges from good to moderate. It is not uncommon to see hourly values in the hazardous range within U.S. embassy compounds in the most polluted cities. Foreign Service members and others can track hourly values for their posts on EPA’s Airnow.gov international page. [Note: In April 2025, this page was removed. Some Foreign Service members may still be able to track local hourly values from the BAM monitor at their post.]

The harmful effects of air pollution over a long period of time cannot be overstated. A recent study using satellite data in Madagascar found that from 2005 to 2018, nitrogen dioxide, which is linked to lung cancer and heart disease, increased significantly in Antananarivo. Worldwide, many low-income nations are experiencing rising air pollution and health impacts, especially in the most populous urban areas.

Madagascar relies on slash-and-burn agriculture; wood-burning stoves for cooking; and fossil fuels for cars, trucks, and buses that share the road with pedestrians. Typical sources of air pollution also include smoke from industrial facilities, brick and charcoal manufacturing, and forests, which are frequently burned to create agricultural land and charcoal. Many vehicles do not meet international emissions standards, burning diesel, leaded, or low-grade fuels that are not permitted in higher-income countries. Combined, these sources create troubling levels of emissions.

If we could procure air quality measurements elsewhere in Madagascar, we would understand how air quality varies from place to place and learn where and how often Foreign Service members on the island were being exposed to poor air quality.

Special training for embassy health units on the effects of air quality on health would provide a consistent and well-informed response to this serious issue. ESTH officers like me could work with medical unit staff and health technicians at post to promote air quality awareness, perhaps with a week of social media, news briefings, events, and speakers—similar to EPA’s annual Air Quality Awareness Week in the United States.

Just as the military tracks health risks for those who serve, the Department of State should track long-term exposure to unhealthful air quality over the course of a career for Foreign Service members. The department, perhaps through OES, could work with health experts and our counterparts at the EPA and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to analyze the effects on vulnerable family members and share their findings. The State Department recognizes our service at hardship posts, but are the long-term detrimental effects of poor air over the course of our overseas service factored into this equation?

What We Can Do

Air Quality Monitor Program Paused

On March 4, 2025, the IoT Network, which is used to transmit data from the Air Quality Monitoring Program to the EPA’s AirNow and other websites, was paused due to funding issues. U.S. citizens abroad, including U.S. diplomats and their family members, have relied on this data in more than 80 cities globally to understand local air quality conditions and better assess their risks of both short- and long-term pollution-related illnesses.

Although we cannot control foreign government policies, the State Department does ensure new embassies are built with high-quality air circulation to provide clean air while at work. We have an opportunity to build on this department effort. For example, the EPA and the department could work together to create a threshold for air quality exposure by post and over the course of a career. As I learned in Madagascar, a yearly average masks seasonal and daily fluctuations to which we are exposed during our commute, our daily jog, and when our children play outdoors. Setting a threshold would help to inform and protect us and our families while we serve our great nation abroad.

But a threshold is not enough—we want to do everything we can to protect Foreign Service members and our families when they leave the embassy or consulate compound. Just as the EPA provides standards for emissions back home in the U.S., the State Department could provide air filters to every household that meets a threshold of pollution during any given day or season. We could work with embassy schools to purchase air filters and schedule outdoor sports and play during lower pollution times of the day. In this way, we could promote clean air both at work and at home, for ourselves and our loved ones.

With my Madagascar tour behind me, I find myself reflecting on the many Foreign Service members and their families serving in cities with high levels of air pollution. When serving our country abroad, we must also look after ourselves and our health. While the Department of State might send us wherever the wind can take us, we can all do our part to increase awareness and mitigate health risks to ensure that wind is safe to breathe.

When sharing or linking to FSJ articles online, which we welcome and encourage, please be sure to cite the magazine (The Foreign Service Journal) and the month and year of publication. Please check the permissions page for further details.

Read More...

- “The Air We Breathe: Living with Air Pollution” by Nicole Shaefer-McDaniel, The Foreign Service Journal, October 2016

- “Tracking Air Quality: Data for Our Community and Beyond” by Mary Tran, The Foreign Service Journal, October 2021

- “AI Air Quality Forecasting: A State-NASA Partnership” by Mary Tran, The Foreign Service Journal, September 2024