Reimagining the Foreign Service EER

Speaking Out

BY JASON RUBIN

Speaking Out is the Journal’s opinion forum, a place for lively discussion of issues affecting the U.S. Foreign Service and American diplomacy. The views expressed are those of the author; their publication here does not imply endorsement by the American Foreign Service Association. Responses are welcome; send them to journal@afsa.org.

The State Department’s employee evaluation report (EER) fails to achieve two key objectives of any effective performance evaluation system: identifying candidates for promotion and providing constructive feedback to employees. Additionally, artificial intelligence (AI) is quickly undermining what little value our narrative-focused format provides, as the technology turns even benign accomplishments into compelling texts that algorithmically maximize scoring rubrics.

It is past time to imagine a more quantitative framework that reduces reliance on employee-written narratives, combats rating inflation through a weighted scoring system, and emphasizes core competencies over circumstantial accounts of achievements.

Recent calls from leadership to reform the department’s recruiting, performance, and retention standards present a unique opportunity to design an evaluation system that fosters real leadership, enhances accountability, and recognizes employee potential.

Evaluating a Memoir

We often joke that the EER process is little more than a “writing contest,” but that’s a remarkably accurate description. Even in its ideal form, where supervisors determine the content for the rater and reviewer sections, the narratives still frequently fail to distinguish candidates for promotion and provide zero constructive feedback to employees.

Problem 1: Failure to distinguish between candidates. Lacking discrete performance measures or context of an employee’s relative performance, promotion boards must intuit how an employee’s character, interpersonal skills, and intellect compare to peers based on wildly differing personal accounts. It goes beyond comparing apples to oranges: It’s as if the board is comparing each fruit’s taste and appearance based solely on the fruit seller’s written account.

Because the department has identified core precepts that FSOs should demonstrate, we should skip the obfuscation step and simply rate each employee directly against those criteria.

This would not only eliminate the self-aggrandizing narratives that paint every FSO as a savior of American interests but would also force supervisors to take ownership of observing, mentoring, and shaping their employees’ work—areas where too many of our leaders fall short.

Problem 2: Failure to provide meaningful feedback. The current narratives, often written by rated employees themselves, undermine a leader’s ability (and responsibility) to provide constructive and actionable feedback to subordinates.

To avoid hurt feelings, we accept wildly exaggerated descriptions of accomplishments that paint even poor performers as heroes. This meaningless flattery diminishes the accomplishments of our top employees and, more importantly, fails to address problematic (yet often correctable) performance issues.

Instead of giving everyone a participation trophy and lauding every new spreadsheet as a “revolutionary tracking system,” we should force leaders to provide honest and constructive feedback to employees on their strengths and weaknesses.

Problem 3: The emerging AI challenge. One might argue that with its rapid adoption, AI would level the playing field for mediocre writers who struggle to make their EERs stand out, but it will likely just shift the advantage from prolific writers to technically savvy prompt engineers who can optimize content for grading rubrics.

Regardless, as AI capabilities inevitably improve, promotion boards will find it even harder to meaningfully distinguish between candidates.

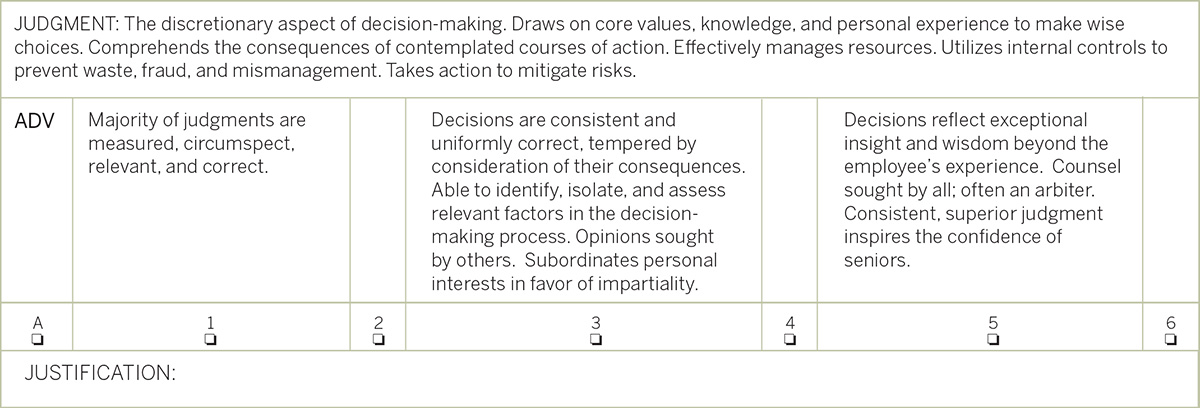

Figure 1: Sample of a Scoring Block

Example of a rater scoring block for a precept element. “A” indicates adverse performance. A score of 1 represents the baseline for a high-functioning employee, followed by gradually increasing levels of performance. The criteria will guide raters toward an appropriate score and reduce grade inflation. Employees should meet all criteria in the example to achieve the score, so a grade of 6 would indicate exceeding all of grade 5 criteria, something akin to the top 0.01 percent of all peers in the department. Justification is required only for adverse or exceptionally high ratings. (Adapted from the U.S. Marine Corps performance evaluation form and existing State Department precept definitions.)

The Solution: A Quantitative Evaluation Framework

A proven solution to our dysfunctional EER already exists. Facing similar irrelevance of its performance evaluation system, the U.S. Marine Corps completely revamped its rating system in 1999, eliminating rampant grade inflation and bringing accountability to rating and reviewing officers.

Marines initially resisted the dramatic overhaul, doubting its ability to change decades of entrenched attitudes and fearing the loss of their “pristine” evaluation records. However, it quickly reset the evaluation baseline and is now universally accepted as improving the fairness and accuracy of evaluations.

The department can easily adapt a similar framework to the unique demands of the Foreign Service.

Abandon the autobiography, embrace quantitative scoring. The new EER would adopt a discrete scoring system, organized by core precepts and key competency areas.

The form eliminates personal narratives, instead providing abbreviated comment sections to justify certain assessments. For each precept, raters only need to include justification text when assigning “adverse” or exceptionally high scores (4 or above). Reviewers then rank staff against peers across the entire department to assess their suitability for promotion. This would standardize evaluation criteria, allowing boards to compare apples to apples and to focus promotion selection on competencies that demonstrate an ability to perform at the next level.

It would also shift evaluation responsibility from the individual employee to the supervisor, forcing leaders to make objective assessments and acknowledge those best suited for promotion.

This would significantly reduce the writing required to prepare reports, avoiding the massive dip in productivity that occurs every spring while everyone is busy crafting complex narratives.

Establish a high-performance baseline. The design of the rating system recognizes that Foreign Service personnel are by and large highly qualified professionals. The descriptors for a baseline score of 1 match the performance of a dedicated, talented, and competent employee—what one might consider a B+ student.

By setting a high baseline and including descriptions of truly exceptional performance, we can push raters away from grade inflation so only the best qualified candidates stand out. This low-score weighting is further reinforced by the third, and perhaps most important, element.

Weight scoring. What ties this system together is its pairing with a “grading curve” for each rater and reviewer to compensate for individual grading biases. Promotion boards would see a weighted relative value for each score based on the rater/reviewer’s entire scoring history for a peer cohort.

For example: Supervisor A tends to inflate scores and rates FS-4 Jones as a 5 in leadership. Supervisor B tends to skew scores lower, rating FS-4 Smith as a 3 in leadership. If Supervisor A’s historical average for all FS-4s is 4.5 and Supervisor B’s historical average is 1.5, the weighted score shown to promotion boards would correctly indicate Smith’s higher relative leadership score.

The Marine Corps’ experience with this weighted system revealed that it not only normalized rating variances but also nudged raters/reviewers to score lower on the scale to preserve scoring space for true top performers. Combined with the high baseline, this encourages honest assessment while avoiding “hurt feelings” for leaders who still struggle with direct constructive feedback.

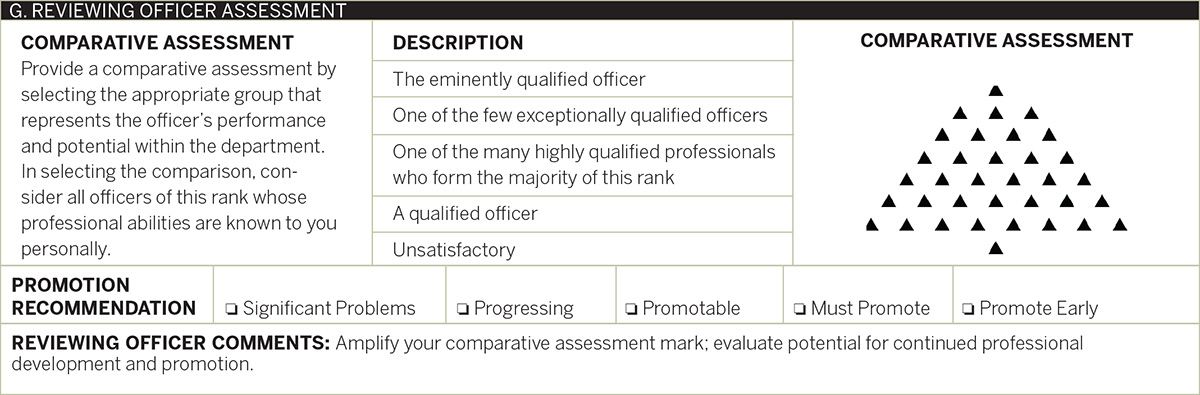

Figure 2: Sample Reviewer Section

An example of a reviewer section. The reviewer ranks the employee among all peers in the department by selecting the most appropriate description block. The “tree diagram” visually depicts the workforce distribution for each ranking option, nudging reviewers to assign more employees in the lower (yet highly qualified) blocks. The reviewer also assesses the employee’s suitability for promotion. (Adapted from two military branch forms.)

Structural Elements of the New System

While the department could copy and paste existing precepts into this proposed system, we have an opportunity to go one step further and refine our focus on an employee’s demonstrated characteristics and impact.

If framed properly, these criteria would be equally relevant to officers of all ranks, further eliminating wasted effort narrating the nuanced context of every position in the department.

Here (see box, below) is one vision of a framework that evaluates across 12 elements of four core precepts.

While these precepts represent just one view of evaluation criteria, our current EER’s failure to capture some of these characteristics indicates major gaps in how we think about what makes a quality leader and what employees need to succeed at higher levels.

Implementation Mechanics

A Possible Framework

- Mission Accomplishment

- Performance

- Substantive and technical expertise

- Initiative

- Leadership

- Leading others

- Developing others

- Effectiveness under stress

- Management

- Organizing projects and managing tasks

- Accountability and integrity

- Resource optimization

- Intellect and wisdom

- Communication

- Decision-making ability

- Judgment

A simplified rater scoring process. Accepting that the vast majority of employees perform their jobs well, scores between 1 and 3 do not require justification. Raters only need to write justification text for adverse scores or values above 3.

Instead of wasting effort building context and recounting a year’s worth of accomplishments in narrative form, these short text blocks substantiate why the employee’s performance falls outside the expected range (see Figure 1, above).

Reviewer’s verification and ranking. The reviewer section focuses on validating the rater’s assessment, serving as an accountability check against grade inflation from a more experienced leader with a broader perspective on organizational norms.

The reviewer also directly ranks the employee’s performance against department peers. A weighted formula is also applied here to correct raw rankings so they mirror the expected workforce distribution, with most employees in the mid-range and very few “unsatisfactory” and “eminently qualified” outliers (see Figure 2).

Accounting for small sample sizes. A combination of statistical adjustments, procedural safeguards, and training would be used to compensate for raters with limited rating histories. These tools are critical during the initial implementation phase when all raters/reviewers lack a historical record.

Statistical tools like “shrinkage estimation” or Bayesian modeling can bias new raters’ scores to departmentwide means, gradually phasing out as a rater’s sample size grows.

Promotion boards would see a rater/reviewer’s record size, relative rankings, and cohort norms, helping them base promotion decisions on a comprehensive picture.

The reviewer’s validation of a rater’s score forces them to work directly with raters to align scores with organizational norms.

Most important, the department would provide practical training to reviewers, raters, promotion board members, and rated employees on grade expectations and organizational norms.

Promotion board review. The quantitative rating system is not designed to reduce promotion decisions to blindly selecting candidates with the highest “GPAs.” Just like the Marine Corps’ system, the promotion board’s subjective review of the “whole employee” remains critical to promoting the best candidates.

While job performance is integral to promotion decisions, boards should also consider breadth of experience, career progression, and job responsibilities over time.

Time for Change Is Now

Change is difficult, especially in an entrenched bureaucracy as large and old as the Department of State. However, organizations unwilling to adapt to real-world changes or reflect on their own shortfalls are doomed to stagnate and fail.

I have yet to meet an FSO of any rank who thought our EER system was a fair and accurate assessment of performance or potential—even among those who have clearly benefited from it. Facing emerging technologies like AI and a major restructuring of how we conduct diplomacy, we must change how we recruit, promote, and retain our employees.

The proposed reforms would empower leaders to honestly evaluate and develop their subordinates, enable promotion boards to identify top performers across all posts and positions, and address the real challenges AI presents in undermining our already negligibly useful self-narrative framework.

While no perfect evaluation system exists, we can—and must—do better. By adopting a more quantitative framework, the department will create a fairer, more effective, resilient system that recognizes exceptional talent and puts leaders in a position to best lead and develop their staff.

When sharing or linking to FSJ articles online, which we welcome and encourage, please be sure to cite the magazine (The Foreign Service Journal) and the month and year of publication. Please check the permissions page for further details.

Read More...

- “FS Personnel Evaluation, 1925-1955: A Unique View” by Nicholas J. Willis, The Foreign Service Journal, March 2016

- “Evaluation Reform at State: A Work in Progress” by Alex Karagiannis, The Foreign Service Journal, April 2020

- “Why Our Evaluation System Is Broken and What to Do About It” by Virginia Blaser, The Foreign Service Journal, April 2023