Why the Office of War Information Still Matters

Established in 1942, the OWI popularized a global vision for the war effort—underscoring the importance of public diplomacy for U.S. national security today.

BY NICHOLAS J. CULL

OWI research workers in May 1943.

Library of Congress

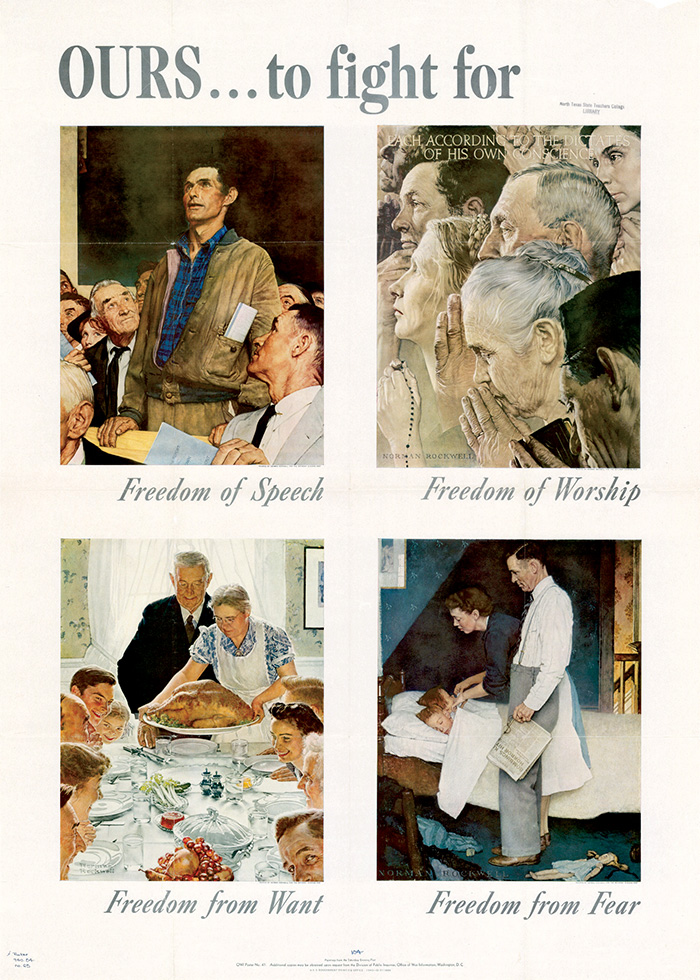

The Office of War Information produced this large color poster, of which 4 million sets were printed from 1943 to 1945. The poster features the four freedoms as illustrated by Norman Rockwell whose paintings famously depict American culture and everyday life.

State Library of Ohio

Eighty years ago, in 1942, in the wake of the attack on Pearl Harbor, the United States government launched a new federal agency to oversee wartime communication work at home and abroad. The Office of War Information became an essential element of America’s domestic war effort in World War II, shaping a swathe of Hollywood films, mounting radio broadcasts and designing posters that remain in the collective imagination (think of Norman Rockwell’s groaning Thanksgiving table to illustrate “Freedom from Want”).

Fully 80 percent of OWI’s budget was devoted to its international work, and in this respect, this predecessor to the U.S. Information Agency marked a milestone in U.S. statecraft. Despite the evolution of communication technologies in the intervening years, OWI’s foreign activity still merits attention. Seen in retrospect, it shows that communication is full of dilemmas and inherently difficult to manage—whether one is dealing with the tension between policy and ideology on the one hand and a reporter’s objectivity or personal agenda on the other, or with the inevitability of “unintended consequences,” or with disinformation and psychological warfare.

More than anything else, however, OWI’s history points to and illustrates the vital importance of public diplomacy to national security that is no less true today than it was 80 years ago.

A Belated Realization

OWI’s international work was born from a belated realization in Washington, D.C., that propaganda and global communication had become essential to modern statecraft. During World War I, the United States had virtually overnight built a global communications network under the Committee on Public Information, successfully propagating Woodrow Wilson’s vision of the peace abroad if not at home. But the structure had not survived into peacetime. Moreover, though friendly nations and competitors alike stepped up media outreach with state-sponsored radio stations and international cultural agencies during the interwar period, the U.S. government had remained largely aloof.

The United States had no equivalent to the BBC Empire Service radio (established in 1932) or the British Council (established in 1934). When, in 1929, Weimar Germany stunned the world with its cutting-edge contribution to the Barcelona Expo, the U.S. government was absent. The U.S. contribution to the Expo in Paris in 1937 underwhelmed, whereas the pavilions built by Nazi and Bolshevik propagandists at the height of their game put the competition quite literally in the shade.

The Roosevelt administration used sophisticated media tools to sell its New Deal at home but was late to develop a capacity for communication in foreign policy. Initiatives were initially limited to educational exchanges with Latin America launched as part of the Good Neighbor policy. The fall of France in the spring of 1940 prompted a change of heart, and a flurry of U.S. government communication activity followed, including external programs.

At times, Voice of America broadcasts were at odds with U.S. foreign policy.

In the summer of 1940, FDR appointed Nelson Rockefeller to the new role of Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs to further develop cultural and economic contact with Latin America with a dedicated office of the same name within the Office of Emergency Management. Then, in 1941, Roosevelt launched a Foreign Information Service, which included U.S. Information Service (USIS) posts around the world to assist foreign media. In the early weeks of 1942, FIS began shortwave broadcasts that eventually became known as Voice of America (the name was surprisingly fluid during the war). But the patchwork of activity lacked coherence.

Seeking to bring a level of order to wartime communication, FDR signed Executive Order 9182 on June 13, 1942, establishing a single Office of War Information.

Establishing the Centrality of Public Diplomacy

OWI drew VOA and almost all wartime communication initiatives into a single home. Only Nelson Rockefeller’s Latin America work remained outside the corral. (It helped to be a friend of the president.) An avuncular CBS radio journalist, Elmer Davis, oversaw the new agency as its director. New Deal speechwriter and playwright Robert Sherwood oversaw foreign activity. The agency’s constituent elements included offices encouraging helpful content in movies, domestic broadcasting and magazines, and even popular fiction.

Overseas, OWI further developed the Foreign Information Service program. It expanded the USIS network and opened libraries in major cities around the world. It worked in partnership with the Office of Strategic Services (precursor agency to the CIA) and the British Political Warfare Executive to create a Political Warfare Division that used propaganda effectively as a force multiplier on the battlefield. Its achievement after D-Day in accelerating enemy surrender in the European theater turned General Dwight D. Eisenhower into a true believer in the value of a psychological approach.

Though separate from State, OWI’s range of overt communication activities toward Allied and neutral publics established media as an enduring component of U.S. diplomacy. It was the predecessor to postwar U.S. public diplomacy work, overseen during the Cold War by the United States Information Agency. During World War II, State had its own cultural attachés, and an assistant secretary of State for public and cultural relations position was created in December 1944 to which Archibald MacLeish was appointed. OWI offices overseas were subject to chief-of-mission authority, and some were collocated in embassy buildings. State simply took over OWI’s international functions in the immediate postwar period.

While OWI increased its reach by guiding the media production of others, it had its own in-house creations for export, including the bimonthly magazine Victory, which launched in December 1942. OWI also made and distributed its own documentary films, which mixed representation of the war effort with insights into American civic life. Prime examples included “The Town,” a portrait of Madison, Indiana, created by the great Austrian filmmaker Josef von Sternberg in 1943.

An audience favorite, “Autobiography of a Jeep” told the story of the GI’s favorite vehicle as if in its own words. The high point in the documentary war came in 1945 when OWI won an Academy Award for a color documentary feature co-created with the U.K. about the Allied advance from D-Day, “The True Glory.” Some of these films remained in circulation through USIA for decades to come.

Handling Disinformation

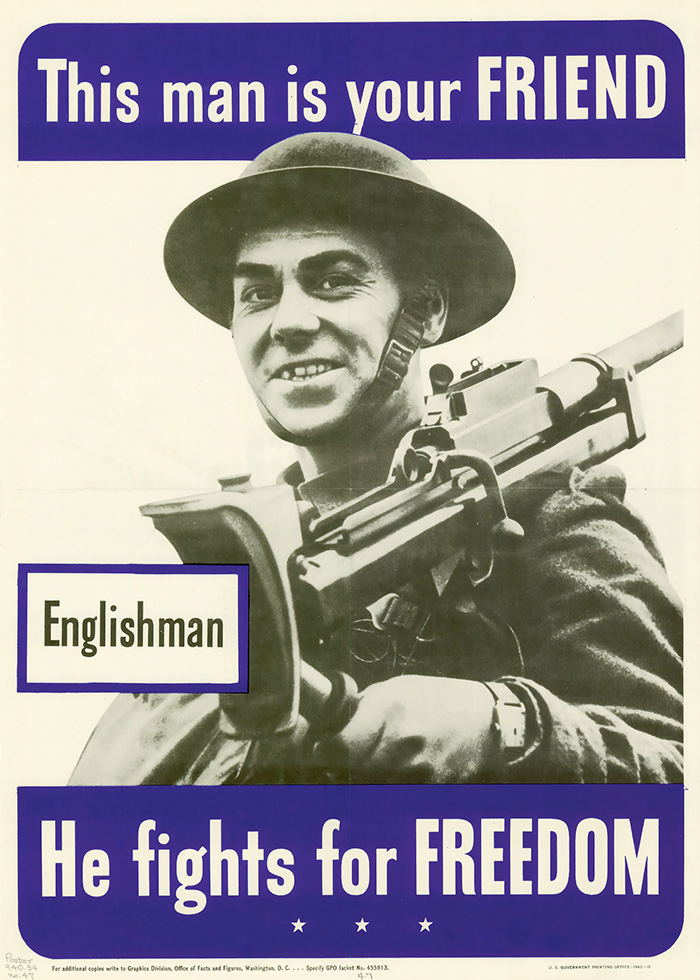

This poster came from the U.S. Office of Facts and Figures in 1942, months before the Office of War Information was established. There were six posters in the series, each with a soldier from a different Allied country.

University of North Texas Libraries

The experience of OWI can be instructive for today’s communication dilemmas; its response to disinformation at home is a case in point. OWI experts were convinced that Germany would use disinformation to undermine the U.S. war effort and began systematically studying U.S. public opinion for signs of German rumors, using a network that included teachers and hairdressers as rumor collectors. Analysis of the rumors suggested that Americans were quite capable of undermining their country without Hitler’s help. Homegrown rumors predominated, mostly based in the enduring cancer of domestic racism. While some in the agency suggested a radio program to repeat and rebut rumors, wiser heads at OWI realized that rebuttals tended to increase the currency of rumors.

OWI resolved rather to focus on the greater vision: selling the positive image of an America in which racial difference was subsumed within an integrated war effort. OWI pressed for African American service characters to join radio soap operas as a reminder of the Black community’s role in the war. Similarly, at a time when racist fantasists reported that Jews were exempt from military service, OWI’s Bureau of Motion Pictures encouraged war films in which brave Jewish characters served shoulder-to-shoulder with other American ethnicities in the plane, platoon and submarine. Today the films are remembered, but the rumors are long forgotten.

OWI’s international broadcasting had its own ambitions and issues. Broadcasts in the German-language transmission began with the admirable promise: “The news may be good. The news may be bad. But we shall tell you the truth.” OWI broadcasts were, however, more complicated. The out-put sometimes included material that was deliberately tendentious, such as programming intended to demoralize U-boat crews. (It was only later, during the Cold War, with the division of labor between Voice of America as a softball voice and the CIA-sponsored Radio Free Europe and its sister Radio Liberation [later renamed Radio Liberty] playing propaganda hardball that the VOA’s identity as a bastion of objectivity could truly emerge and be eventually enshrined in the charter of 1960.)

The effectiveness of the OWI broadcasts was widely noted. On one occasion, when the captured captain of U-662, Heinrich Eberhard Müller, not only confessed his enjoyment of the broadcasts but also asked to meet the broadcaster known as Commander Bob Norden, a meeting was duly arranged with the man behind the nom de guerre Norden, Ralph G. Albrecht of the U.S. Naval Reserve. A skilled German-language speaker, Albrecht went on to serve on the prosecution team at the Nuremberg war crimes trial.

Conflicting Aims and Unintended Consequences

Tension between government policy and the political views of individual reporters also surfaced. Some Voice of America writers were overly enthusiastic about the U.S. alliance with the Soviet Union, and a few at OWI and VOA were explicitly affiliated with the Communist Party. At times, Voice of America broadcasts were at odds with U.S. foreign policy. One of the most notorious clashes came as Italy left the war in July 1943. A VOA report included a reference to the “moronic little king” of Italy and dubbed the interim leader of the country a “high-ranking fascist.” The slip made the front page of The New York Times. Other slips became visible only in retrospect.

As concerns increased, the Roosevelt administration cleaned house. Some leftwing writers bridled at the turn to what they saw as boilerplate patriotic propaganda at home and left the agency. The administration moved out other political writers associated with the New Deal and promoted veterans of the commercial media as voices of the mainstream. Some communists were explicitly fired. The widespread OWI sympathy toward the Soviets led to misrepresentation of some important episodes during the war. VOA misreported the massacre of 20,000 Polish officers in the Katyn forest, for instance, as a Nazi atrocity rather than a crime committed by the forces of Stalin.

Part of the effort in foreign policy must include explaining the approach to the domestic audience.

In other battles, Director Elmer Davis argued for the integration of Japanese Americans into the war effort and for a more honest representation of the battlefield, including images of American dead. In due course, the War Department conceded and deployed Japanese Americans in the European theater. On the latter issue, understanding the need to damp down the expectations of the victory-hungry audience at home, the War Department allowed more of the horror of war to be visible in the work of combat photographers such as Robert Capa. OWI worked hard to ease the passage of American troops into Allied and, eventually, former-enemy territory, and helped to avoid major tensions with locals. Its outposts were often celebrated for their contributions. The OWI library in Cape Town, South Africa, for example, was remembered for many years as a major influence in the modernization of that country’s libraries and a voice for political reform.

Perhaps most important was OWI’s central role in popularizing a global vision for the war effort. Yet even here there was a catch. All propaganda comes at the price of unintended consequences. The agency’s output emphasized the need for a collective effort, not just to win the war but to rebuild the world afterward. OWI helped lay the foundation for creation of the United Nations structure and ensured the domestic American enthusiasm for this project that had been missing in 1919. OWI built up expectations of the postwar system, overstating the degree to which the machinery would align with U.S. interests, exaggerating the capacity of some allies and the willingness of others to help. The bump of reality was damaging at home. When the valiant Chinese ally depicted by OWI crumbled under the pressure of a communist insurgency, the United States did not ask who misrepresented China between 1942 and 1945 but rather who lost China in 1949.

An Essential Capability

Elmer Davis, here seated at his desk, was appointed the first OWI director by President Franklin Roosevelt in 1942. Before joining, he worked as a reporter for The New York Times and later as a popular news analyst for CBS Radio.

Library of Congress

OWI was disbanded immediately after the Japanese surrender in August 1945, its domestic elements wound down and its foreign elements transferred to the State Department. The Harry Truman administration had accepted a report early that summer that argued that information work was an essential component of foreign policy. It seems that an innate discomfort with the idea of a government presence in communication at home in general and the OWI’s track record of controversy hastened the process.

Seen in retrospect, the experience of OWI shows that communication is inherently difficult to manage. OWI had extreme difficulty reconciling the government’s need to communicate policy and ideology with the interest of journalists at VOA in delivering objective coverage or, in some cases, advancing personal political agendas. The military were reluctant partners throughout. OWI got a lot wrong. Its exaggerations set the United States up for a disruptive postwar reality check. Over-reliance on left-of-center journalists in its early years made OWI a favorite target of anti–New Deal Republicans.

The controversies continued into the postwar period, though by the 1950s, when Senator Joseph McCarthy took aim at VOA, real cases of disloyalty were a thing of the past. VOA had a rough passage into its postwar incarnation as an official international radio station with a core mission to report objective news. Its enemies included the Associated Press, which hated the idea of the government providing the same commodity for free—news—for which AP charged.

Eighty years on from the launch of OWI, it is important to look honestly at the agency’s record. Then, as now, the bottom line is that engagement of foreign publics matters, and that part of the effort in foreign policy must include explaining the approach to the domestic audience. It needs effort, creativity, leadership and a structure to reconcile the internal tensions between policy and reporting. Then, as now, we need international partnerships to overcome our shared problems; and partnerships require someone to articulate a compelling vision of a shared destination.

Today, like 80 years ago, is no time to neglect public diplomacy. It seems absurd that budgets for public diplomacy are so hard fought, and that positions like the under secretary of State for public diplomacy and public affairs kept vacant. A neglect of the military would provoke an outcry. It is time for a similar concern over the neglect of what Dwight Eisenhower called the psychological factor in foreign affairs.

Read More...

- “The Office of War Information,” The Foreign Service Journal, October 1942

- “Propagandists in World Affairs,” by Orville C. Henderson, The Foreign Service Journal, February 1953

- “Recalling Dec. 11, 1941: When World War II Truly Began,” by Ray Walser, The Foreign Service Journal, December 2021