Blue-Ribbon Blues: Why So Many Great Reports and Good Ideas Go Nowhere

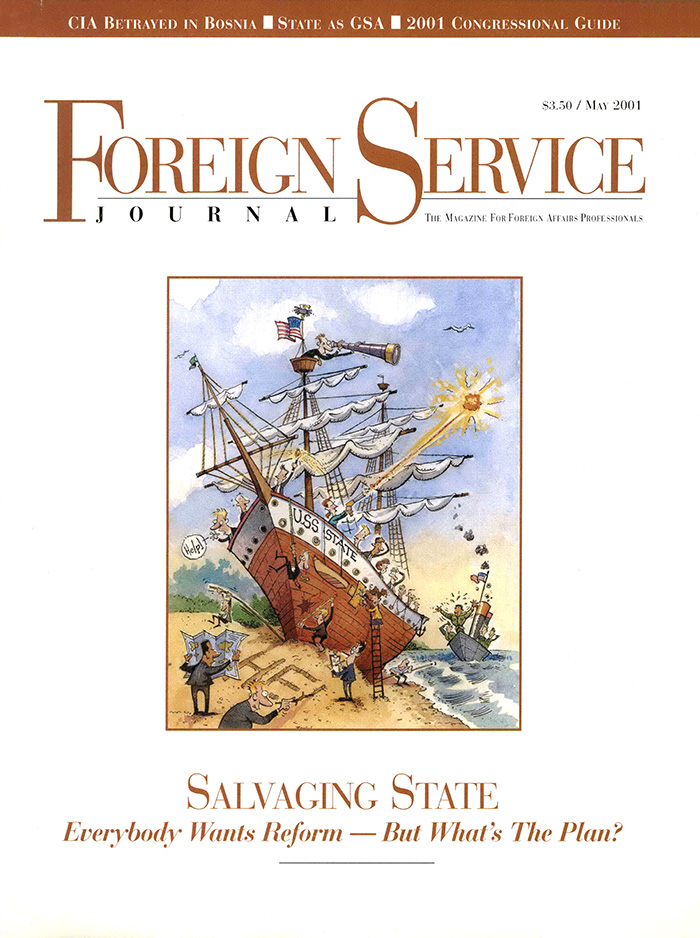

Reform efforts at State are perennial. Several critical institutional issues have been studied again and again for decades to scant effect. Why is change so difficult?

BY HARRY KOPP

In 1968 the American Foreign Service Association published a lengthy report, “Toward a Modern Diplomacy,” containing specific recommendations for improvement in the organization of the nation’s foreign affairs. Among other things, the authors stated that training should occupy about 10 percent of a Foreign Service career and be a “virtual prerequisite” for promotion.

“There have been many studies of the Foreign Service,” said Ivan Selin, the State Department’s under secretary for management, in 1989. “We’ve averaged one per year for the last 30 years.” Output has scarcely dropped off in the decades since.

Studies of the Foreign Service and the Department of State rarely reveal problems not already widely known. Even more rarely do they produce the results their authors want. Ideas and proposals for change often founder on three obstacles: resistance, impracticality and inertia. Deep research and sound argument may not carry far. One former ambassador, often called upon to serve on commissions whose work was ignored, expressed his frustration: “You give ’em books and give ’em books,” he said, “but all they do is eat the covers.”

This article looks at three tough issues that have been repeatedly studied to scant effect: dual personnel systems, interagency coordination and professional development.

A Single Service

Resistance and inertia thwarted early proposals to merge the State Department’s Foreign Service and Civil Service employees into a single personnel system. The Commission on the Organization of the Executive Branch of Government (called the Hoover Commission after its chairman, former president Herbert Hoover) met from 1947 to 1949 pursuant to an act of Congress. The commission’s foreign affairs task force argued for a single service, in which all members would be available for foreign and domestic assignments and subject to selection out. Only a merger, the task force argued, could heal the “cancerous cleavage” between the two services that burdened management and sapped morale.

Dean Acheson, named Secretary of State in 1949, had served on the task force and supported the merger. As Secretary, however, he had his hands full negotiating the creation of new international alliances and institutions in the wake of World War II, and defending himself and his department against vicious attacks from the Republican right. He left the merger question alone. “The Secretary,” he later wrote, referring to himself in the third person, “regarded a far-reaching and basic reorganization of every person in the department as General Grant might have regarded a similar proposal for the Army of the Potomac between the Wilderness and Appomattox.”

Nevertheless, the idea of a single service across the Department of State seemed so sound that it appeared again and again in various forms for the next 25 years. Studies by the Rowe Committee (1950), the Brookings Institution (1951) and a White House personnel task force (1953) repeated the Hoover Commission’s proposal with little variation—but no action followed. When the idea appeared for a fifth time, in a 1954 study by a State Department committee on personnel (chaired by Henry Wriston, president of Brown University), Secretary John Foster Dulles took some 1,500 civil servants into the Foreign Service and opened a like number of Civil Service positions in the department to Foreign Service members—but he kept the two services separate and distinct.

State’s claim to responsibility for interagency coordination in foreign affairs is easy to assert, but hard to enforce.

During the mid-1960s, proponents of a single service brought the idea back in altered form in a bill that passed the House. In the Senate, however, former Foreign Service Officer Claiborne Pell (D-R.I.), a member of the Committee on Foreign Relations, grew concerned that a merger would cost the Foreign Service its elite status. The bill died in committee. Deputy Under Secretary for Management William Macomber then tried to accomplish administratively what the bill would have placed into law; but his efforts were opposed by Civil Service unions and overturned in federal court in 1973.

The cleavage between the department’s two personnel systems— not to mention a third system, for increasingly numerous non-career political appointees—remains a challenge for management and a source of occasional workplace friction. Employees with different wages, benefits, rights and obligations mesh uneasily into the “one team” the Secretary of State asks for and deserves. It is a pity that when solutions were offered and possible, they failed to be adopted.

The Interagency

Studies and directives that deal with the problem of policy coordination across agencies, in Washington, D.C., or in embassies overseas, have offered solutions marked by impracticality or wishful thinking. In 1949, the Hoover Commission noted, more than 45 agencies had representatives overseas. The Department of State and the Foreign Service accounted for only about 11 percent of U.S. government civilian employment abroad, and less than 5 percent of the budget for international affairs. With so few resources at its command, said the task force, the Department of State should concentrate on coordination of the overseas work of those agencies tasked with programmatic responsibilities and endowed with the wherewithal to carry them out.

Neither the numbers nor the argument have greatly changed in the decades since. Presidents, Secretaries of State, members of Congress and numerous wise observers have echoed the commission’s desire to have State organize the government’s efforts abroad. In 1951 President Harry S Truman wrote to Secretary of State Dean Acheson: “The Secretary of State, under my direction, is the Cabinet officer responsible for the formulation of foreign policy and the conduct of foreign relations, and will provide leadership and coordination among the executive agencies in carrying out foreign policies and programs.”

SOS for DOS: A Call for Action

In an unusual “grassroots” reform initiative, a group of Foreign Service and Civil Service employees presented a detailed “call to action” to Secretary of State Colin Powell in February 2001. Having gathered under the banner of “SOS for DOS,” they were convinced that leadership needed to urgently “undertake a long-term, bipartisan effort to modernize and strengthen the Department of State.” Here are excerpts from their call.

United States leadership in a post- Cold War world requires a rigorous foreign policy and robust diplomacy attuned to the realities of the present, not the past. ... The Department of State is ill-equipped and ill-prepared to meet the foreign policy challenges of the 21st century. Outdated procedures and chronic resource shortages have taken their toll. The organizational structure is dysfunctional, its staff is overextended and many of its embassy buildings are crumbling. The State Department’s traditions and culture block needed change while its dedicated employees are distracted with trivia and drift without a common institutional vision. Multiple studies have identified the problems. We must act now to make the needed repairs.

We must—

- craft a clear plan of action to modernize and renew our organization, procedures and infrastructure.

- transform our outdated culture and demonstrate a clear commitment to change.

- embrace new technology and managerial techniques quickly.

- integrate policy and resource management in ways that advance national interests and promote operational efficiency.

- make a clear and compelling case for how we will use any new resources needed to underwrite and sustain a modernized and reinvigorated Department of State.

We ask for the support, involvement and leadership needed to undertake a long-term, bipartisan effort to modernize and strengthen the Department of State. The era of quill pen diplomacy is over. At the dawn of the 21st century, we call for bold and decisive steps now to deal effectively with the problems of today while preparing for the challenges of the future—a future that is as close as tomorrow.

—From “Are State Employees Ready for Reform?”

by Shawn Dorman, FSJ, May 2001.

In 1961, after years of hearings, Senator Henry “Scoop” Jackson (D-Wash.) lamented: “State is not doing enough in asserting its leadership across the whole front of foreign policy.” In 1966 President Lyndon Johnson, who tried to manage foreign affairs with a hierarchical system of interagency groups under (usually) State Department chairmanship, assigned the Secretary of State “authority and responsibility … for the overall direction, coordination and supervision of interdepartmental activities” overseas.

One of the bluest of blueribbon commissions, Ambassador Robert D. Murphy’s 1975 Commission on the Organization of the U.S. Government for the Conduct of Foreign Policy, urged that consistency in policy required the department to “monitor, oversee and influence foreign activities of other agencies”—but judged that State was not up to the task. In 1998 the Stimson Center, in a report called “Equipped for the Future,” discovered again a “profusion of agencies” operating overseas and found the United States “deficient” in interagency coordination. Another commission, the Secretary of State’s Overseas Presence Advisory Panel, complained in 1999 that “though the nation’s overseas agenda involves more than 30 federal departments or agencies, there is no interagency mechanism to coordinate their activities.” Two years later, a study for the Council on Foreign Relations by Ambassador Frank Carlucci, the Foreign Service officer who rose to become Secretary of Defense, offered a similar judgment: “Foreign policy has been undermined by ineffective interagency coordination.”

Calls for the department to assert greater programmatic and operational leadership intensified after the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001. In December 2005, as the situation in Iraq deteriorated, a presidential directive ordered the Secretary of State to “coordinate and lead integrated United States government efforts … to prepare, plan for and conduct” stabilization and reconstruction efforts, in Iraq and around the world. But neither the White House nor Congress provided new resources for that purpose, and State’s coordinating role remained unclear.

Two years later, the Secretary of State’s Advisory Committee on Transformational Diplomacy, acting as if the 2005 directive did not exist, called on the president to “make an explicit statement underscoring the Department of State’s role as the lead foreign affairs agency.” In 2010 the department’s first Quadrennial Diplomacy and Development Review said that State “react[s] to each successive conflict or crisis by reinventing the process for identifying agency leadership, establishing task forces, and planning and coordinating government agencies.”

At embassies abroad, the chief of mission is responsible by law (per the Foreign Service Act of 1980) for the “direction, coordination and supervision of all government employees in that country (except for employees under the command of a United States area military commander).” The Foreign Affairs Manual currently contains 19 numbered paragraphs listing chief-of-mission responsibilities: among them are opening markets for U.S. exports, halting arms proliferation, preventing conflict, countering terrorism and international crime, upholding human rights and promoting international cooperation on global problems such as the environment, narcotics and refugees. And these are just in paragraph one.

Responsibility, however, does not convey authority. As Carlucci wrote in 2001: “Ambassadors lack the authority necessary to coordinate and oversee the resources and personnel deployed to their missions by other agencies and departments.” Six years later, a study of country teams by Ambassador Robert B. Oakley and Michael Casey Jr., reached the same conclusion: “Ambassadors do not have adequate explicit authorities to unify the efforts of the country team.” In its QDDRs, the department implored ambassadors to lead their missions “in a CEO-like manner”— without, however, acknowledging that CEOs, unlike chiefs of mission, control their budgets and personnel. Even within the department, the proliferation of bureaus, not to mention special envoys and other single-purpose entities, has diffused authority and made internal coordination slow and painful.

State’s claim to responsibility for interagency coordination in foreign affairs is easy to assert, but hard to enforce. Having ceded policymaking to the White House and National Security Council, the Department of State sees the coordinating role as its central purpose. But its vision is not widely shared. Other agencies do not clamor for State, in Washington or overseas, to constrain their freedom of action or direct their energies away from their own priorities. When State adds value to the work of other agencies, it succeeds in leading whole-of-government operations. But despite years of studies, exhortations and occasional presidential directives, the department has yet to secure a broadly acknowledged, institutional position as interagency coordinator.

Training and Education

For 70 years, studies of the Foreign Service have identified a lack of specialized skills and the absence of systematic in-service training as serious institutional shortcomings. And for 70 years, the department has addressed these problems without much seriousness of purpose. State management may feel strongly about training and professional development, but not strongly enough to place them above other claims on its resources.

The Foreign Service Act of 1946 established the Foreign Service Institute to provide a “continuous program of in-service training … directed by a strong central authority.” FSI immediately fell short. In 1954, the Wriston Committee found FSI to be “almost paralyzed: it exists on crumbs that fall from the Air Force table. Career planning is conspicuous by its absence.” The Service, said the committee, was “critically deficient in various technical specialties—notably economic, labor, agriculture, commercial promotion, area-language and administrative—that have become indispensable to the successful practice of diplomacy.”

The committee recommended that FSI be “revitalized” and “elevated to the level of the war colleges” by revising its curriculum and strengthening its faculty. Under Secretary of State Charles Saltzman, a committee member, said that the Foreign Service needs a “deliberate career training plan” and called on FSI to develop one. Placing FSI “on a level with the various war colleges,” said The Foreign Service Journal, “received the full support of Secretary [John Foster] Dulles.” The department instituted a mid-career course and expanded opportunities for coursework outside FSI.

Fast-forward to 1968. FSI is still not “on a level” with the war colleges, and long-term training remains sketchy. Such training, said the reform-minded FSOs who wrote “Toward a Modern Diplomacy,” should occupy about 10 percent of a Foreign Service career and should be a “virtual prerequisite” for promotion. No steps were taken to make that a reality.

The authors of the Foreign Service Act of 1980 found it necessary to include a legislative instruction to the Secretary to establish a professional development program. In 1986, the department convened a committee (chaired by FSO Ray Ewing, then dean of the language school at FSI) that found in-service training “either non-existent or irrelevant.” The training involved inexperienced teachers and course material that was “outdated or patently not germane to the professional development of the students,” stated the committee. In 1989, two studies of the Foreign Service personnel system, one commissioned by Congress and one by the department, called for more training time for FSOs. The departmental study recommended adding 50 positions to FSI and giving monetary incentives to encourage training. “Everyone,” said the under secretary for management, “believes there has to be more training” that is “tied in with assignments … not just for general character building.”

‘It’s Hard to Tend the Tree…’

Since the end of World War II, “reform”—which is to say, change, for better or worse—has been a permanent feature of the Foreign Service landscape. About every decade a major reform has been proposed and implemented.

Between those initiatives, a plethora of committees, commissions and study groups have kept the State Department and the other foreign affairs agencies under scrutiny, with the threat of further change ever present. As the great Foreign Service director general, Nathaniel Davis, once noted, “It’s hard to tend the tree when every couple of years someone pulls it out of the ground to see if the roots are growing.”

Ambassador Davis makes a cogent point. Who among us has not thought, “Why don’t ‘they’ just leave us alone and let us get on with it?” Well, there is one very good reason why “they” won’t leave us alone. Contexts change over time, so all institutions, public or private, must reinvent themselves to deal with new realities—or perish. In the commercial sector the list of iconic companies (think RCA) that have disappeared is long. The list of corporations successfully reinventing themselves (IBM) is much shorter.

The Foreign Service and State Department face the same imperative: adapt or disappear. The reality of the continuing need for reform is directly linked to the rapidly changing world of the 20th and 21st centuries.

—From “The ‘Reform’ of Foreign Service Reform”

by Thomas D. Boyatt, FSJ, May 2010.

“Everyone” still believed that in 1993, when the department released another study, the excellent State 2000: A New Model for Managing Foreign Affairs. This study found a “mismatch between what we want to do and the skills of those we expect to do it” and recommended three steps to address the problem: workforce planning to identify future needs, a “requirements-based hiring system” to recruit to needs that have been identified, and long-term training to develop professionals with “functional/area expertise and managerial competence.”

But as Foreign Service numbers fell under the budget-cutting policies of the 1990s (the end of the Cold War’s so-called “peace dividend”), training was sacrificed to operational demands. Two 1999 studies, McKinsey & Company’s “The War for Talent” and a report by the Secretary of State’s Overseas Presence Advisory Panel, called for rapid action to improve training and professional development.

Secretary of State Colin Powell (2001-2005), accustomed to the rigorous, systematic training provided to Army officers, was determined to create a “training float”—an excess of people over regular positions—of about 15 percent. His Diplomatic Readiness Initiative added some 2,000 employees to the Foreign Service between 2000 and 2004 for that purpose. And training, measured by student hours, did increase by about 25 percent.

After 2004, however, the need for training gave way again, this time to staffing demands in Iraq and Afghanistan. In 2008, a study by the Stimson Center and the American Academy of Diplomacy (an association of former career and non-career ambassadors and senior officials) found that the Foreign Service lacks “to a sufficient degree” such skills as “foreign language fluency; advanced area knowledge; leadership and management ability; negotiating and pre-crisis conflict mediation/resolution skills; public diplomacy; foreign assistance; post-conflict/stabilization; job-specific functional expertise; strategic planning; program development, implementation and evaluation; and budgeting.” These shortfalls, the study found, “are largely a result of inadequate past opportunities for training, especially career-long professional education.”

Congress approved two more increases in the State Department’s Civil and Foreign Service workforce, a modest increase in 2008 and a surge from 2009 to 2013, the centerpiece of the Diplomacy 3.0 initiative of Secretary of State Hillary Clinton (2009- 2013). By 2015, State’s Foreign Service had grown by 40 percent, and its Civil Service by 45 percent, over 2002 levels. A third of the Foreign Service had fewer than five years’ experience.

The department’s second QDDR, released in 2015, promised to invest in training, including “long-term training that develops expertise and fresh perspectives.” The department had on hand a blueprint for deep reform of professional development in a 2012 paper by AAD and the Stimson Center, “Forging a 21st-Century Diplomatic Service for the United States through Professional Education and Training.” Once again, the moment seemed right for establishment of a sustainable training float and the integration of training and education into a Foreign Service career. Quick action might have led to progress, but once again the department let the moment pass unseized.

Then a wildly hostile Trump administration slammed the window of opportunity shut. As reported in the December 2017 Foreign Service Journal, Ambassador Nancy McEldowney told The New York Times that in the early months of 2017, when she was still director of FSI, “My budget was cut. … I could not hire anyone, even when I had vacant positions. I could not transfer people within my organization or from elsewhere inside the State Department. … There was a political appointee sent out … who reviewed our training materials and objected when there was reference to American foreign policy under the Obama administration.”

Clearly, FSI was not to be “elevated to the level of the war colleges.” That 50-year old goal remains out of reach, and receding.

Change Is Hard

Why is change so difficult? Donald Warwick, a Harvard sociologist, published the book A Theory of Public Bureaucracy: Politics, Personality and Organization in the State Department in 1975. Time has only confirmed his findings.

“Executive agencies,” Warwick wrote, “show the influence of organized interests, personal whims, political brokerage and sheer bureaucratic inertia.” State Department employees who resisted a Foreign Service-Civil Service merger, or officials in other agencies who resist State’s efforts to coordinate them, are highly intelligent people who strive to protect their positions and do their jobs to the very best of their abilities. As Warwick writes, they have “much the same motivation for security and selfesteem as the rest of the population.”

In other words, do not blame the bureaucrats: they are people too. Their behavior is predictable and rational. It needs to be taken into account. Proposals for change based solely on considerations of organizational efficiency will have little effect, and managers who act on such proposals will likely fail.

Bureaucratic behavior cannot explain 70 years of shortfall in training and professional development, however. The fault here lies with the department’s leadership, which always seems to find assignments other than training more important for its workforce. Perhaps the political leadership of the department, eager for accomplishment before the end of its term, has less interest in improving the long-range strength of the career services than in addressing the issues of the moment. The department has rarely had leaders willing to sacrifice short-term opportunities for benefits that will show up only in some future administration.

History may be depressing, but it is also instructive. Change is difficult, but possible. Reforms must be well thought out and supported by evidence. They must attend to the desire of members of the Foreign and Civil Services to carry out their missions, excel at their work and secure their futures. And they must be driven by a leadership that values the department as an institution, with a past and a future as long as the republic’s. Under those conditions, the report of the next blue-ribbon commission or departmental task force will find its audience and lead to action.

Studying State

Studies of the Department of State and the Foreign Service come along nearly every year. Here are some from across the decades that still merit attention.

| Year | Author | Full Title | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1949 | Hoover Commission | Task Force Report on Foreign Affairs of the Commission on Organization of the Executive Branch of the Government | Commission established by act of Congress. President Harry S Truman named former President Herbert Hoover chairman. |

| 1954 | Wriston Committee | Toward a Stronger Foreign Service: Report of the Secretary’s Public Committee on Personnel | Committee convened by Secretary of State John Foster Dulles. Henry Wriston, president of Brown University, served as chairman. |

| 1962 | Herter Committee | Report of the Committee on Foreign Affairs Personnel | Sponsored by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Former Secretary of State Christian Herter was committee chairman. |

| 1968 | American Foreign Service Association — Committee on Career Principles | Toward a Modern Diplomacy | Graham Martin, committee chair; Lannon Walker, chair of AFSA’s board of directors. |

| 1970 | Department of State | Diplomacy for the 70s: A Program of Management Reform for the Department of State | The work of 13 task forces convened by Deputy Under Secretary for Management William Macomber. |

| 1975 | Murphy Commission | Report of the U.S. Commission on the Organization of the Government for the Conduct of Foreign Policy | Commission created by act of Congress. Ambassador Robert D. Murphy served as chairman. |

| 1993 | Department of State Management Task Force | State 2000: A New Model for Managing Foreign Affairs | Study requested by Secretary of State James Baker. William Bacchus was executive director of the task force and principal author. |

| 1998 | Stimson Center | Equipped for the Future: Managing U.S. Foreign Affairs in the 21st Century | John Schall, principal author. |

| 2001 | Frank Carlucci and Ian Brzezinski | State Department Reform: Report to the President | Sponsored by the Council on Foreign Relations and the Center for Strategic and International Studies. |

| 2008 | American Academy of Diplomacy and the Stimson Center | A Foreign Affairs Budget for the Future: Fixing the Crisis in Diplomatic Readiness | Support from Una Chapman Cox Foundation. Ambassador Thomas Boyatt, project chairman. |

| 2015 | American Academy of Diplomacy | American Diplomacy at Risk | Project team: Thomas Boyatt, Susan Johnson, Lange Schermerhorn, Clyde Taylor. |

| 2016 | The Heritage Foundation | How to Make the State Department More Effective at Implementing U.S. Foreign Policy | Brett D. Schaefer, principal author. |

| 2017 | Atlantic Council | State Department Reform Report | Report requested by House Foreign Affairs Committee. Kathryn Elliott, principal author. |