The Future of the Foreign Service—As Seen Through the Years

The following are selected excerpts from FSJ coverage of the future of the Foreign Service over the years.

Change As a Means to Improved Foreign Relations

We must never forget that from the nation’s point of view the only thing that really matters is whether or not the foreign affairs job is performed ably and successfully. There is nothing sacred about either the department or the Foreign Service; they are administrative mechanisms to serve the national interest. They can and should be altered from time to time to remedy their deficiencies and to improve their effectiveness.

We cannot, then, logically object to change, provided that change is a means toward the objective of more effective conduct of American foreign relations. We must assume, however, that even the most ardent administrative prestidigitators will sooner or later have to take morale factors into consideration. No administrative mechanism can be better than the people who staff it, and the devotion of these people to their duties. Over the long pull, changes cannot be so frequent or so drastic as to keep employees in a state of uncertainty and unrest. There needs to be enough stability through the years so that the foreign affairs organization can consistently recruit topflight talent, provide genuine career satisfactions, and keep its employees working with maximum loyalty and devotion.

What I do argue, however, is that we must adjust ourselves to the frustration of never being popular and never being fully recognized for our efforts and our achievements. It is no use to say that the department falls down on its public relations and doesn’t know how to tell its story effectively. In future years we may do a better job in this respect than we are doing now, but the problem is by its nature inherently not subject to a full solution.

—Frank Snowden Hopkins, assistant director, Foreign Service Institute, from “The Future of the Foreign Service,” FSJ, April 1950

A Broader Definition of the Diplomatic Calling

The crisis confronting diplomacy in the 1980s can only be understood as part of the much larger crisis confronting the nation-state. Despite all the frenzied manifestations of nationalism and the proliferation of new nations, the basic reality to the latter part of the 20th century is that “One World” is rapidly becoming a fact. The steady and inexorable shrinkage of the planet to the dimensions of a global village, combined with quantum leaps in the advance of technology and the social and economic development of hitherto backward regions is daily making the nation-state more obsolete at every level of international intercourse. As this process accelerates, the traditional modalities and instrumentalities have become too narrow and stereotyped to accommodate the traffic.

If the State Department wants to assume primacy over the full range of official relationships binding the United States to other nations, its personnel will need to concentrate on non-governmental levels of host country societies to a greater extent than has hitherto been regarded as part of the diplomatic function.

This can only be done by broadening the personal contacts of mission personnel to include youth, labor, intellectual and clerical circles at one end of the spectrum, and private financial, business and celebrity circles at the other. Investment patterns and currency transactions are especially important.

There is scarcely a society in the world where indicators of impending change are not visible in every comer—provided an embassy officer speaks the local language, keeps himself open to unofficial contacts, and spends some of his time with intelligent citizens instead of his bureaucratic counterparts.

—Charles Maechling Jr., from “The Future of Diplomacy and Diplomats,” FSJ, January 1981

How Can the Foreign Service Remain Effective for the Next 60 Years?

In 1984 the Journal asked a group of prominent individuals for their thoughts on the future of the Foreign Service. Here are excerpts from a selection of responses from the November 1984 FSJ.

I can confirm your assumption that the Foreign Service is currently effective in the development and implementation of U.S. foreign policy. As we face the future, however, the big question is whether the Foreign Service will evolve as dynamically as the international environment in which it operates.

The key words for the future are high technology, multilateralism and economic interdependence. Bilateral relations will always be important; but most new problems overflow national boundaries and straddle domestic and international affairs. The complex issues of technology transfer, international debt and terrorism are current cases in point.

FSOs should consider broadening their horizons as much as possible. Assignments outside areas of specialization, outside the department and, indeed, outside of government will be extremely valuable to officers who will face difficult issues in the high-tech, electronically fused world of 2000 and beyond.

Increasingly, government will have to work closely with the private sector to achieve foreign policy objectives. The Foreign Service will have a unique role in bringing the best assets of both to bear on the continuous process of pursuing U.S. interests around the world. Foreign Service officers and specialists must expand their horizons to develop and maintain the necessary skills and intellectual mobility.

—George P. Shultz, Secretary of State

To remain effective for the next 60 years, the Foreign Service should strive to set ever higher standards of professionalism and dedication, and the Congress must encourage and help the Service in this quest.

The Service must seek constantly to increase the number of officers who speak needed foreign languages. More emphasis must be placed on achieving higher language skill levels and on maintenance of those skills.

The Service must recruit the best candidates—highly intelligent persons willing and able to serve under difficult and dangerous conditions abroad. But we must be willing to pay what it costs to attract and keep them.

The Service must deal with the professional interests of its members’ spouses. We do not want a Service of separated families— it would not be sustainable over the next 60 years or project adequately our American values of family and home.

Finally, each administration must responsibly choose only well-qualified political appointees. There have been many superb political appointees named for high State Department and ambassadorial posts, but others have not had the background or experience for the job. The Foreign Service has problems, but they are manageable. I am sure that the Service will improve upon its already distinguished record of dedication and achievement over the next 60 years.

—Charles H. Percy, chairman, Senate Foreign Relations Committee

In the years ahead, the Foreign Service must adapt to major additions to the diplomatic agenda. Our record in this is not good. Our traditional view of diplomacy as essentially political did not prepare us to assume roles in development and information in the postwar years. Our inability to convince others of our dedication to trade lost us the commercial function. Political leaders’ doubts regarding our sensitivity to domestic currents have seen us bypassed in foreign policy.

Already we have many new agenda items: arms control, transfer of high technology, allocation of radio frequencies. Others lie ahead in potential conflicts over transnational data flow, the availability of positions in space, the impact of outer space development on national sovereignty and the implications of biotechnological innovations. The Foreign Service must begin to develop officers who understand technology and speak the language of the technicians. If not, others will replace us who can.

Perhaps only after one has been out of the Service for a few years does the awareness dawn of how isolated the Service is, immersed in its own pressures, concentrating on other societies, and rooted in the protection of traditions and turf. Presidents and political leaders may not wait for such a traditional service to catch up. They will look elsewhere for the help they need. It is time for the Foreign Service to prepare itself to be responsive to the needs of the future.

—David D. Newsom, former under secretary for political affairs

One of the major recent changes affecting the Foreign Service is the heightened participation of Congress in foreign policymaking. I believe this trend will continue for the foreseeable future.

In recent years, the Service’s isolation from the legislative domain has been breaking down. More and more mid-level FSOs have served in exchange programs with the Congress and have become directly involved in congressional testimony. This enhanced contact and communication between two branches of our government means that future FSOs will have to be more than researchers, drafters of cables and policy papers, and able negotiators: They will have to become effective advocates of executive policies and programs. Selection and promotion procedures should reflect this new and added requirement.

Administrations, it is said, have varying programs and policies, but nations have permanent interests. The Foreign Service needs to develop public recognition of, and support for, its basic and continuing mission—which is to defend and promote the U.S. interest abroad, in the fullest sense of that term.

—Dante B. Fascell, chairman, House Foreign Affairs Committee

One thing is certain: if humanity survives on this planet, political structures and foreign affairs will still be moved by people acting and reacting with each other. This is what the Foreign Service is about. Our people are our only asset, and we must devote increasing attention to them. We must increase our capability to understand and anticipate the changes that science and technology are bringing to human relations in finance, economics, politics and military affairs so that we can be ahead of the curve instead of frantically trying to catch up. We must also better develop our domestic constituency to give our citizens and political leadership confidence that our objective is the protection and promotion of the interests of this country in their largest and best sense. If we are successful, we should regain that primacy in foreign affairs under the president to which we should aspire.

—U. Alexis Johnson, former under secretary for political affairs

The problem, as I see it, is not what the Foreign Service needs to do to remain an effective force in the next 60 years, but what the United States government needs to do to the Foreign Service to give it that possibility. This, in my opinion, would be to return to the sound principles of the Rogers Act of 1924: to make the Foreign Service—a highly selected and unashamedly elite body of professionals, held to high standards of discipline, performance and deportment, but respected accordingly—a self-administering service, to be entered only at the bottom and by strict and impartial competitive examination.

The Foreign Service should not be confused with the various bodies of technicians and specialists that are involved in other capacities in the external relations of our government, and it should be quite immune to political manipulation. It would be desirable that it be regarded as the normal and primary, though not exclusive, source of appointment to ambassadorial positions and to senior positions in the Department of State, these latter to include, incidentally, the position (yet to be established) of a permanent under secretary of state, on the British pattern, wholly divorced from political affiliation or influence.

—George F. Kennan, retired ambassador

The Foreign Service has only one asset—its people. To remain effective over the next 60 years, more work must be done to maintain the current high-quality FSO corps. In the face of declining attractiveness of government as a career, the increasing role played by other agencies in foreign affairs, and the mounting personal disadvantages in living overseas, the Foreign Service must run harder to stay even. Not only must we address such issues as pay, benefits, and working conditions, including greater opportunities for working couples; but we must come to grips with the seemingly intractable obstacles to maximum performance during the last two decades: mission definition, a more rational allocation of personnel resources, and an organizational structure that clarifies lines of accountability and responsibility.

The good news is that foreign affairs is becoming more central to our country’s interests, indeed even its very survival. The president can and should look to the Foreign Service as his instrument to orchestrate our foreign policy resources. No recent president has fully accepted us in this role, but future presidents may find the need overwhelming. Let’s position ourselves to take advantage of the opportunity when it arises. The first priority is to get our own house in order.

—Frank C. Carlucci, former FSO, chair, Commission on Assistance

Train to Deal with the World As It Will Become

The fundamental purpose of America’s foreign policy is to protect our citizens, our territory and our friends. As we look ahead, we know that increasingly, this will require an effective response to problems that extend far beyond our borders. To function successfully in this diverse, fast-paced and rapidly changing environment, we will need women and men trained to deal with the world not as it was, but as it is, and as it will become.

We will need people who can find the needle of information that counts amidst the haystack of data that do not. We will need people who can function in partnership with those from elsewhere in our government, in other governments and from the private sector. We will need people who can think and act globally—because that is what the American interests require. We must try to improve our record of recruiting qualified women and minorities.

Here at FSI, we will need more focused training in issues such as trade, climate change, refugee law and information management, while maintaining a high standard on cultural studies and language skills.

While so doing, we cannot and will not ignore the more traditional aspects of diplomacy. We will maintain our focus on key alliances and relationships around the world. But we also know that, in the future, our FSOs and other professionals will be asked to range far from the bargaining tables and communication centers of our largest embassies.

Today, the greatest danger to America is not some foreign enemy; it is the possibility that we will ignore the example of the generation that founded FSI; that we will turn inward; neglect the military and diplomatic resources that keep us strong; and forget the fundamental lesson of this century, which is that problems abroad, if left unattended, will all too often come home to America.

—Secretary of State Madeleine Albright, from “The FSO of Tomorrow,” FSJ, May 1997

Resources for Diplomacy Have Become Inadequate

Diplomats will not be replaced by CNN, e-mail or telephone calls between political leaders. Human contact and informed analysis on the scene will remain essential to making and implementing foreign policy. The new international agenda will place greater premium than before on professional skill in cross-cultural communication, negotiation and coalition building.

Resources for diplomacy have become inadequate. For fiscal 1998, the Clinton administration has requested restoration of some cuts, but further reductions in subsequent years proposed by both the administration and Congress will, if enacted, cripple America’s ability to promote its international interests. For budget purposes, diplomacy must be addressed for what it is: a central component of our national security.

The United States no longer confronts a superpower rival, but the issues faced are more frustrating, more technical, more diffuse. Americans will be concerned primarily with challenges that must be addressed by coalitions of nations, often in multilateral forums. Most of these issues are not susceptible to unilateral American action.

The mission of the Foreign Service will thus extend beyond its traditional responsibilities. Since the national interest calls for coherence and balance in foreign policy, another central role of the Foreign Service becomes clear: to coordinate and guide American specialists from a variety of agencies, and sometimes the private sector, in the international dimension of their work. In fact, foreign affairs experts will sometimes find they must mediate among conflicting domestic points of view to arrive at consensus on national positions.

—William C. Harrop, from “The Future of the Foreign Service,” FSJ, May 1997

The Professional Training Imperative

The zeal with which the Foreign Service constantly re-examines its structure and missions and reappraises its training needs honors our passion for our profession, but also makes it difficult to reach conclusions about how effective such changes have been over the years. The most widespread method within the Foreign Service for imparting wisdom about how to do the job and pursue a career continues to be mentoring, whether conducted formally or simply through the example set by more senior officers.

This is famously illustrated by the story of Secretary of State Colin Powell, who spent more than 20 percent of his military career undergoing professional development that he found useful. When he asked his under secretary for political affairs, Marc Grossman, how much time he had spent in professional training over the course of his Foreign Service career, Grossman replied: “Two weeks, aside from language instruction.”

While considerably more training has been added since this exchange, mentoring remains the core of our professional development. But that model has already begun to break down in the face of rapid personnel increases, and is manifestly inadequate for future needs.

As retirements continue and the influx of desperately needed new officers expands, we are at the point where almost two-thirds of Foreign Service officers have spent fewer than 10 years in the Service; 28 percent have spent fewer than five. We simply no longer have sufficient experienced officers to serve as mentors and trainers. And this reality will not be changed by mandates that each deputy chief of mission find time to mentor all entry-level officers at his or her post—an approach that increasingly resembles King Canute’s orders that the sea withdraw.

—Ronald E. Neumann, from “The Challenge of Professional Development,” FSJ, May 2010

The Power of Decency and Diversity

The world is obviously an increasingly complicated place. Compared to the moment when I entered the Foreign Service in January of 1982, power is more diffuse in the world—there are more players on the international landscape. Diplomacy is no longer, if this was ever the case, just about foreign ministries and governments. It’s about nongovernmental players. It’s about civil society groups and private foundations, as well as the forces of disorder, whether it’s extremists or insurgents of one kind or another.

And on top of all that, information flows faster and in greater volume than at any time before. So the challenges for professional diplomats are, I think, as great as I’ve ever seen them. But I continue to believe that our work matters as much as it ever has. Our ability to add value and to help navigate a very complicated international landscape in the pursuit of our interests, remains enormously significant.

That should be a source of pride, not just for our generation of Foreign Service officers, but for succeeding generations, as well. And, fortunately, as I speak to A-100 classes and to our colleagues around the world, I am continually struck by the quality of the people with whom we work. I’m impressed when I see the range of experiences in the A-100 classes, not to mention diversity of ethnicities and gender. I wouldn’t say these issues have been overcome, because we still have a long way to go, but I think we’re making progress. And that’s important.

In my experience overseas, I’ve seen that we get a lot further through the power of our example than we do by the power of our preaching. When you see a Foreign Service that looks like the United States, and which is the kind of living embodiment of tolerance and diversity, I think that sends a much more powerful message to the rest of the world.

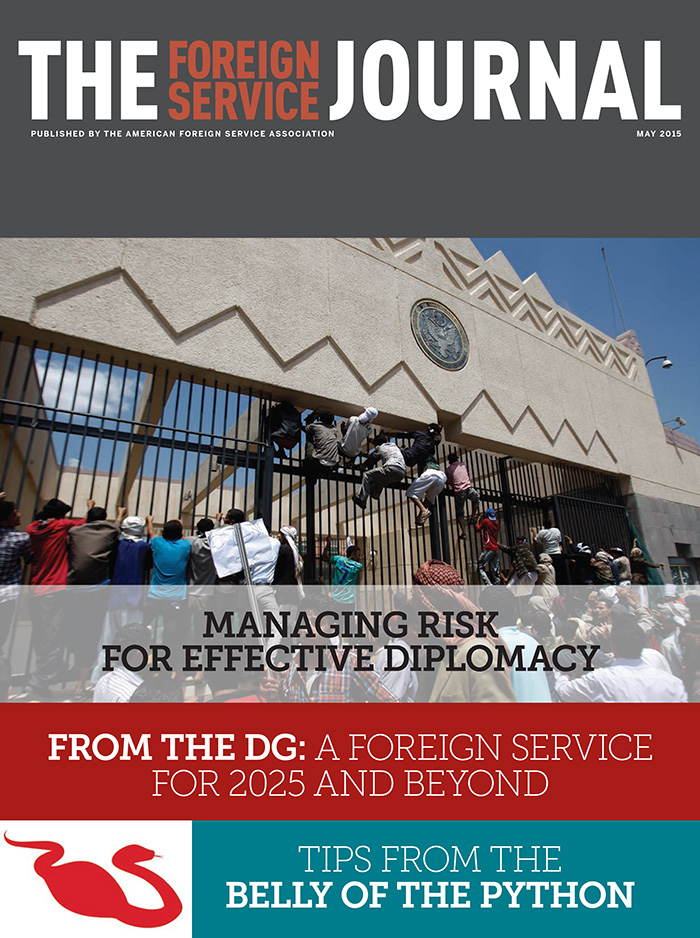

I think we’re learning about how to serve in the often-disorderly world of the 21st century. We’ve still got a way to go. There’s some hugely important issues, like how to manage risk. We’ve sometimes learned very painful lessons. There is no such thing as zero risk in the work that we do overseas.

We can’t connect with foreign societies unless we’re out and about. But making those judgments about what’s a manageable risk, and what isn’t, is increasingly difficult. So we’re still wrestling with a lot of those kinds of challenges, as well. I do think we’ve learned a lot. As a Service, we’re better positioned to deal with those types of challenges than was the case a decade or so ago.

—William J. Burns, from “A Life of Significance: An Interview with Deputy Secretary of State William J. Burns,” FSJ, November 2014

America’s Front Line

Since 2002, the Foreign Service has grown 42 percent, with 22-percent growth since 2008. (On a parallel track, State’s Civil Service has grown 45 percent since 2002.) One-third of the Foreign Service now has fewer than five years of experience, and more than two-thirds have served or are now serving at hardship posts.

That earlier surge in hiring has now screeched to a halt, barely keeping pace with attrition. And the outlook is for continued fiscal tightness, even as we risk losing seasoned employees with exceptional experience and expertise to retirement, selectionout or resignation as the economy improves and large cohorts compete for a relatively static number of promotion opportunities at higher grades. The large intakes from the Diplomatic Readiness Initiative and Diplomacy 3.0 now confront the predictable tightening of promotion rates as the number of highergraded positions naturally tapers at mid- and senior levels.

We can predict with high confidence that over the next quarter-century, the world will continue to be a messy place that requires U.S. leadership. We can also forecast that more, not fewer, U.S. stakeholders will look to participate in foreign policy formulation and execution. That means we as a department must be much better managers, especially with regard to our talented employees.

The Foreign Service is America’s front line. We are in the information business: identifying, analyzing, disseminating and making recommendations to prevent, preempt or solve problems. We are also in the networking business: identifying and cultivating programmatically influential people in all fields. And we are in the advocacy business: discussing, negotiating, persuading and convincing others to act with and for us. None of that will change.

At the same time, we know we are not the Foreign Service of 1950, 2001 or even 2010. We need the very best people: the ones who see past the horizon; who are curious, innovative, tenacious; who show initiative, judgment, resilience, adaptability and perseverance. We’ve always had those employees, but it’s more important than ever to attract and prepare a workforce for the future, bearing in mind that such attributes are often best learned and honed through real-life experience.

—Arnold Chacón and Alex Karagiannis, from “Building a Foreign Service for 2025 and Beyond,” FSJ, May 2015