Bringing Order Out of Crisis: Behind the Scenes of a Task Force

Seen through the lens of perhaps the greatest crisis response effort ever—the 2020 Repatriation Task Force—this look into how the State Department organizes emergency responses is an eye-opener.

BY CHRIS MEADE, HOLLY ADAMSON, MERLYN SCHULTZ AND FANY COLON DE HAYES

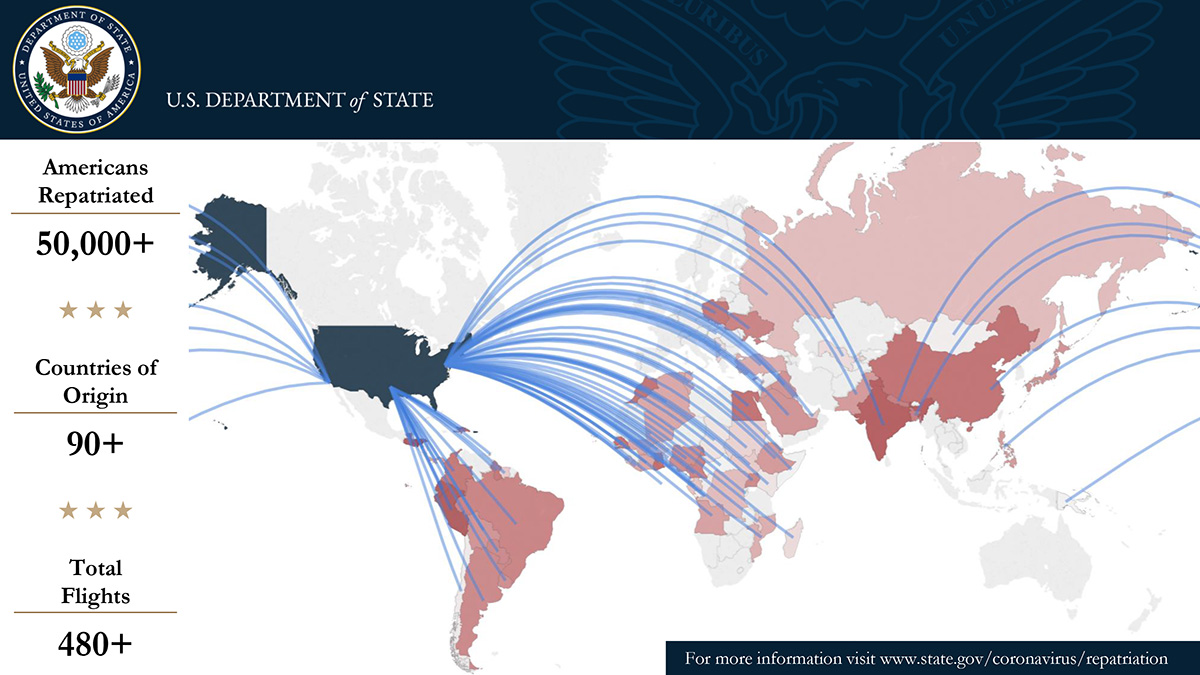

The Repatriation Task Force created this infographic for Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s presentation at the April 8 White House Coronavirus press briefing. As it shows, between Jan. 29 and April 8 the task force brought more than 50,000 Americans home from more than 90 countries around the world in an unprecedented effort that involved more than 480 flights.

U.S. Department of State

Like everyone else in the world, we in the State Department Operations Center’s Office of Crisis Management and Strategy are asking ourselves: “What’s next, 2020?”

Since Dec. 31, 2019, CMS has established, managed and contributed our diverse professional expertise to four 24/7 task forces: the first one to respond to violence in the Middle East and the next three to deal with the COVID-19 pandemic. These task forces harnessed State’s collective expertise to ensure an efficient and successful response.

As of June 5, more than 102,000 Americans had been repatriated with State Department assistance on more than 1,100 flights from more than 139 countries. Even considering our massive evacuation conducted in World War II, this State Department–led, whole-of-government effort was unprecedented. For many Americans, it was their first exposure to the State Department, and we’re proud that so many citizens were able to see the tireless energy, commitment and courage of the countless diplomats across the world who worked to get them home. It was an opportunity for State employees to view the department differently, too, by working directly with a task force and seeing firsthand the global effort that ensured the full U.S. government rose to a historic challenge.

This article pulls back the curtain on CMS’ role managing crises through the prism of this extraordinary year. For CMS, the real story is how we’re able to bring together hundreds of officers—representing more than 130 posts and 30 bureaus and offices—to overcome unexpected technological, logistical and diplomatic obstacles to ensure a strong department response and bring Americans home.

This is a story of thousands of partners, operating around the clock in every time zone in dozens of locations, with information moving at light speed.

When CMS Calls: Activating the Task Force

The story began in 1976 in a windowless office on the State Department’s 7th floor. Established as an office within the Operations Center, CMS had three officers who transcribed conversations of senior principals discussing how to manage emergent crises. Since then, CMS has grown while taking on new responsibilities in response to crises like the 1998 embassy bombings in Dar es Salaam and Nairobi, 9/11 and Benghazi. Today’s 20-person office is nearly equally split between Foreign Service officers and civil servants.

Strategically located down the hall from the Secretary of State on the 7th floor of the Harry S Truman building, CMS works at the intersection of policy and operations to develop contingency plans ahead of a crisis and mobilize a response if one is needed. Working with the Watch (our 24/7 counterparts in the Operations Center), we alert senior principals in real time to breaking news events.

This is a story of thousands of partners, operating around the clock in every time zone in dozens of locations, with information moving at light speed.

CMS is perhaps best known for establishing and coordinating the department’s task forces, which are activated when a crisis exceeds the ability of an individual post or a bureau to respond. With the support of the director of the Operations Center and in conjunction with the lead bureau affected by the crisis, CMS then recommends to the executive secretary that a task force is needed to respond effectively. CMS has already done the legwork to make sure that a task force will be operational within 60 minutes of a decision. Once approved, CMS activates subject-matter experts from the department and the interagency to work together, side by side, for a rapid, synchronized and comprehensive response.

That task force then serves as the department’s central coordination and information hub, synthesizing situational and operational developments to solve problems, alert and brief senior-level decision-makers and deploy resources in real time.

2020 in Perspective

By all accounts, 2020 has been an exceptional year. We typically activate between one and five task forces a year. But well before this year was half over, we had already stood up four back-to-back task forces—the last one under unprecedented circumstances.

On December 31, 2019, we stood up the Middle East Task Force in response to attacks against U.S. Embassy Baghdad and escalating Iranian aggression that threatened regional stability. Less than a day after that task force moved to on-call status on Jan. 23, we partnered with the Bureau of East Asian and Pacific Affairs for the Wuhan Evacuation Task Force to evacuate our staff at U.S. Consulate General Wuhan and Americans trapped in China after the city was unexpectedly locked down to contain the novel coronavirus.

Within just days of standing down that second task force, we formed the Diamond Princess Evacuation Task Force to evacuate Americans from a cruise ship off the port of Yokohama, Japan. That, too, was a clearly focused mission with specific, measurable objectives.

Then came the biggest, most challenging task force of them all: the Repatriation Task Force. On March 19, with the worldwide spread of COVID-19 escalating and its acknowledgment as a pandemic by the World Health Organization, the Bureau of Consular Affairs and CMS jointly launched the Repatriation Task Force to facilitate the return of thousands of Americans stranded overseas across the world as a result of the widespread shutdown of commercial flights. As of June 24, this task force was in on-call status.

In 44 years of experience responding to crises throughout the world—including 125 evacuations during the last 10 years—the State Department’s CMS had never faced a scenario where the same threat simultaneously affected our colleagues overseas as well as those charged with responding to it in Washington, D.C. That threat uniquely affected establishment of the Repatriation Task Force itself. To set it up, we had to transform the traditional model of a task force—namely, dozens of officers from different bureaus seated side by side to respond nimbly to ever-emerging issues—into something completely new overnight: a complex “virtual task force.”

In 44 years of experience responding to crises, the State Department’s CMS had never faced a scenario where the same threat simultaneously affected our colleagues overseas as well as those charged with responding to it in Washington, D.C.

With more than 400 officers serving as part of the Repatriation Task Force, and tens of thousands of Americans across the world depending on us, we had to stand up and set into motion a virtual task force for the department without missing a beat. It required embracing some new tools quickly, such as information-sharing collaborative technologies and teleconferences, while rapidly creating new techniques to extend our ability to work together in real time from dispersed or far-flung environments.

Tips for Serving on a Task Force

- Stay calm and expect the unexpected. Rephrasing Forrest Gump: “Task forces are like a box of chocolates—you never know what you’re going to get.”

- Do not use the word “quiet” when describing the task force’s operational tempo. Vocalizing this observation during a task force might result in an unwelcome immediate uptick in activity.

- Sleep when you can. Task forces can be taxing on your body; working 24/7 for months on end with 8- to 12-hour shifts takes a toll.

- The legendary “trough” is hard to resist despite your best intentions to maintain a nutritious diet. You’ll find a spread of donuts, pizza, baked goods and refined sugars brought in by co-workers. Make sure you know when items were brought in to weed out expired treats!

- You will rise to the occasion! It will be challenging; however, the reward will be one that you will always remember. A task force is an opportunity to live through history and carry out the Department of State’s core mission to protect and assist American citizens overseas.

—CM, HA, MS, FCdH

Meeting Pandemic Challenges

At the heart of every task force, however, are the tools that each Operations Center officer brings to their job every day: the ability to work quickly, the willingness to adapt to new challenges effortlessly, and the tenacity to tackle some of the most difficult problems. We were able to pivot quickly, amid one of the highest-profile and most complex operational responses that State has ever executed, to implement previously untested tools and technologies while ensuring our vital work continued without interruption.

The effort was not unlike building an airplane in mid-flight. Though most volunteers worked from home, the task force was able to provide the same uninterrupted service and high-quality reporting CMS efforts are known for. CMS developed an on-demand training curriculum to efficiently prepare the more than 400 volunteers who helped the Repatriation Task Force to accomplish its mission.

CMS also created an operational planning team, consisting of the department’s lead operational and logistics planners and regional and functional bureau representatives, to review requirements, expedite the identification of potential air assets and streamline the request for and approval of U.S. government funds to carry out repatriation missions. This new process—robust, replicable and transparent—reduced the approval time from days to a few short hours or even minutes, enabling multiple missions to be planned and executed in rapid succession.

COVID-19 also required outstanding and sustained interagency coordination, including collaboration with domestic agencies across multidimensional problems, some of whom are not State’s usual partners. Working with the Federal Aviation Administration, Transportation Security Administration and Customs and Border Protection, we facilitated more than 1,000 flights landing in the United States, while the Department of Health and Human Services and Federal Emergency Management Agency coordinated with state governors and local emergency management offices to receive evacuees. The Department of Defense hosted more than 800 evacuees from Wuhan and the Diamond Princess, in close collaboration with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Department of Health and Human Services.

Insight into the complexity and unique challenges of the repatriation mission can be gained from considering what’s involved in flight clearances. During a Wuhan evacuation, hundreds of Americans were set to depart on our evacuation flight. After suddenly learning that a bureaucratic snafu—somewhere between Washington, Beijing and Wuhan—was about to derail the flight, with a customs approval spiraling into a flight clearance issue amid the cacophony of babies crying and officials arguing at increasing volume, the task force room grew anxious, and animated. As the minutes ticked down, our tarmac slot, with a plane full of Americans that needed to take off, was due to expire; the Washington Task Force then leapt into action. We rapidly identified senior government officials in China and D.C., initiated contingency and escalation scenarios, and began putting a new plan—and calls at the highest level—into motion.

In the end, the situation was luckily sorted on the ground after intervention from U.S. Embassy Beijing. For us in Washington, clustered on the 7th floor and in teleconferences in operations centers and points across the city, it was a moment of high tension and drama that demonstrated how vital it was to have medical, logistical, diplomatic and operational experts seated side by side, when minutes matter and outcomes are on the line. The Repatriation Task Force marshaled and coordinated this effort, continually synchronizing with interagency partners, governments, medical professionals and others to ensure a seamless, whole-of-government response in real time. Many task forces aren’t quite this pressurized—but, increasingly, many are, with moments made difficult by virtue of multidimensional or multigeographic complexity that demand cohesion and performance from the department and the interagency.

The Wuhan Task Force in action in early February. Clockwise from left to right: Alex Dunoye, Vietnam desk officer; Roger Burton, Crisis Action Team Director, Department of Homeland Security National Operations Center; Sarah Nelson, Consular Section Chief, Consulate General Wuhan; Pamela Kuemmerle, Crisis Management Officer, State Department Operations Center, Office of Crisis Management and Strategy; Holly Adamson, Crisis Management; Rachel Okunubi, Watch Officer, State Department Operations Center; Lindsey Spector, EAP/PD; Michael Cullinan, Watch Officer, State Ops; Valentina Hart, Program Officer, DMD/OM/PM; Stephanie Smit, Branch Chief, Consular Affairs’ Office of Citizen Services/Children’s Issues; Nick Fietzer, Country Officer, CA Office of Citizen Services; and Rob Romanowski, Consular Officer, CA Office of Citizen Services.

U.S. Department of State

Big Problems, Big Data and More

As COVID-19 spread, conditions changed quickly across the globe—new restrictions and closures were imposed by national governments, airports suspended operations and borders were tightened. The data multiplied fast, as did demands for that information by senior leadership, the interagency and posts worldwide. Effectively mobilizing resources—not to mention getting people to the right place at the right time, or just in time—hinged on the department’s ability to see the world swiftly, accurately and comprehensively.

Given the global scope of the operation, CMS had to rapidly establish a worldwide process to collect and synthesize data. To do this, we collaborated with the Under Secretary for Management’s Office of Management Strategy and Solutions (M/SS) to create the COVID-19 Data Analytics Team (CDAT), which would serve as the department’s central hub for all coronavirus-related data. CMS and CDAT worked closely to help decision-makers understand where progress was made and determine where resources should be deployed next.

This common operating picture ensured we could coordinate flight missions on a short timeline to meet demand. With thousands stuck overseas, some with serious health conditions, striking a balance among posts with extraordinarily high demand and our responsibility to smaller posts was tough. Despite the challenges from reduced staffing and suspended operations, embassies and consulates worked tirelessly with the task force to ensure all Americans who needed repatriation assistance were helped.

On a daily basis, the Repatriation Task Force managed the equivalent of diplomatic gymnastics—gaining flight clearances and maneuvering through locked-down borders, coordinating transport out of remote locations, and keeping track of fluid travel restrictions—in lockstep coordination with officers from around the world.

Given the global scope of the operation, CMS had to rapidly establish a worldwide process to collect and synthesize data.

Identifying and relieving bottlenecks in the process of getting Americans home was a constant challenge, especially in the beginning. On one particular task force shift, department logisticians requested help from U.S. commercial airlines for flights from Peru, which closed its borders with little notice. Thousands of Americans saw their return flights canceled and sought repatriation while thousands more Peruvians in the United States wished to return. Meanwhile, private citizens from both countries, along with multiple authorities within the U.S. and Peruvian governments, overwhelmed commercial airlines with requests for information. The task force sought high-level department intervention to harmonize efforts toward a common solution.

Better Prepared to Face Future Challenges

Task forces serve as incubators of best practices and better prepare the State Department for future crises. For instance, from the response to H1N1 and Ebola in 2014, we learned that a pandemic response is often a long-term endeavor that requires a focused engagement that cannot be managed by people still performing their original day jobs; it must extend beyond the operational scope of a task force. In 2020 we acted on those lessons, quickly recognizing that our international response to the coronavirus would need a full-scale coordinated diplomatic, consular, scientific and political response and recovery. CMS proposed and established the Coronavirus Global Response Coordination Unit as a standalone office responsible for the department’s long-term policy and COVID-19 coordination efforts.

As State’s institutional repository of crisis practices, CMS, partnering with M/SS, has already begun convening stakeholders across the building, our embassies and consulates, and the interagency to identify which innovations, systems and approaches pioneered during the COVID-19 response can be carried into the future.

Task forces also build expertise and relationships. Before 2020, many diplomats may never have directly confronted or responded to a crisis in their respective countries, nor had so much of Washington ever collaborated so widely and extensively at the same time. As the department’s crisis management experts, we’ve witnessed the transformative impact of that. Now, more than ever before, new muscle memory has been formed, shared and spread globally across dozens of bureaus, offices and posts. The relationships built, tested and reinforced over the past several months within the department, through the interagency, across Capitol Hill and among hundreds of partners and governments, will benefit the American people for generations.

Those of us in CMS know the department learns invaluable lessons from each crisis we face. We emerge stronger, better prepared and more ready. Responding to the inevitable crises that will emerge over the next year and decade will require not only everything we’ve learned so far, but more. We know our work over the last year, and the 44 years before it, has helped ensure that the department can meet the challenges of tomorrow. We can all be proud of that.

Read More...

- “Nerve Centers 1967 Style,” Victor Wolf Jr., FSJ, August 1967

- “How We Do Our Thing: Crisis Management,” John W. Bowling, FSJ, May 1970

- “What the Department of State Can and Can't Do in a Crisis,” State.gov