Dual Identity and Diplomacy

An Indian American FSO learns to navigate the rocky waters of ethnic and gender identity while serving in India.

BY SANDYA DAS

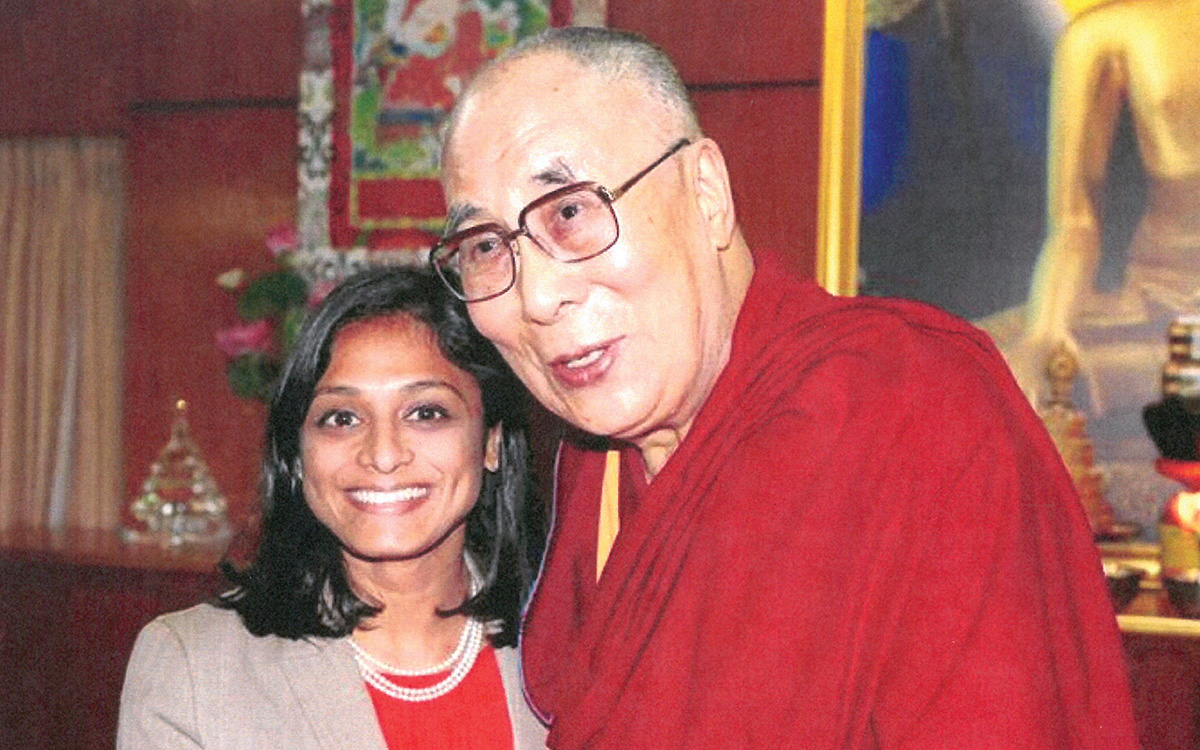

His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama of Tibet with the author in Dharamsala, Himachal Pradesh, India in 2017.

Courtesy of Sandya Das

Newly arrived in the political section at U.S. Embassy New Delhi, I soon set off for Punjab in northern India for my first official visit outside the capital. As a reporting officer, I was tasked to better understand the political and economic situation ahead of assembly elections in a state crippled by corruption, drug abuse and a growing agricultural crisis. I planned to meet with a wide range of locals, from state officials and politicians to journalists, businessmen and civil society activists.

One of my first meetings was with one of the Punjab chief minister’s principal advisers, a six-foot-tall man in his 50s with the traditional Sikh turban—a long piece of white cloth neatly wrapped around his head with his beard coiled up into the headpiece. Wearing a gray pantsuit and with my hair tied back, I reached out my hand, ready for business. After quickly disposing of the requisite greetings, he got right down to his first pressing questions: “Where is your family from? Are you traveling here alone?”

I was taken aback: What on earth does this have to do with anything? I could feel my cheeks flush as I faltered with a response, beginning to suspect that he viewed me as a young, impressionable Indian woman rather than as a U.S. diplomat to be taken seriously. The interaction reanimated many unflattering biases I had about Indian men and their treatment of women that I had developed growing up and through the media. And I was dead certain of one thing: my fair-skinned male colleagues were not facing similar lines of questioning.

Like other American children born to immigrant parents, I went regularly on family trips back to my parents’ birthplace in Kerala to visit relatives. These trips back felt routine, schlepping from one relative’s house to the next, eating sumptuous meals while aunties affectionately pulled at my cheeks. My twin brother and I would sit glued to our portable Gameboys and comic books, competing over who had the most mosquito bites.

But several years later, when I traveled by myself as a high school student to the remote Himalayan foothills of Ladakh, it was as if I were visiting my motherland for the first time. Landing at a remote Buddhist monastery in India’s northernmost state of Ladakh, home of a largely Tibetan Buddhist community, I spent a summer teaching English and math to young Buddhist monks.

Through my time in the classroom, I learned the rigors of my students’ daily lives and how they experienced growing up in India. The teenage boys struggled to read children’s books and solve basic arithmetic problems while facing chronic ear and eye infections in the absence of regular medical checkups. At the same time, I found cultural experiences that we shared, including eating with our hands and always having yogurt at the end of a spicy Indian meal.

Going back to India in high school opened my mind to how my Indian heritage had shaped my core identity. But when I came back years later as an adult, I could tell that I still had a lot more reflecting to do.

Unsure how the different pieces of myself would fit back together, I was determined not to be caught flat-footed about my Indian-ness again, as I had been in Punjab. I started trying to take a different attitude into my interactions with Indians.

In one instance, a politician was so curious about my last name, asking, “Das, now doesn’t that mean you’re Bengali? I can’t get enough of Bengali sweets!” Rather than roll my eyes and try to dodge the friendly questioning, I took the chance to share a little about my southern Indian background, even joking that my last name is common in the South and that Indian sweets are a guilty pleasure of mine, as well.

At other times, it was not as easy to embrace being identified as an Indian woman. During preparations for a high-level summit between our foreign ministers, I had to work closely with two female Indian diplomats. Moving diligently up their service ranks and properly dressed in their freshly pressed saris, they seemed to almost accentuate their British accents, as if to note their formal education.

Greeting my male American colleague, who held a position equal to my own, they smiled and enthusiastically said, “Hello and welcome! So good to see you again.” Though standing right next to my colleague, I received but a quick head nod. Rather than confront the two women and feel ashamed, however, I decided to take a different approach. “It’s a pleasure to see you both again,” I replied before my male counterpart had a chance to respond. “And thank you for working late last night to help us finalize these critical negotiations.”

I slowly learned to navigate such experiences with confidence, despite the occasional discomfort and trepidation I felt. More importantly, I found ways in which my Indian identity was an asset to my diplomacy, helping me bond more closely with people I met—whether through an affinity for Bengali sweets or another shared Indian connection. As the months went by, I began to embrace and fully appreciate my dual identity with a newfound sense of honor and pride.

Toward the end of my posting in India, I was assigned to bring a senior U.S. delegation to meet the Dalai Lama at his home of exile in the hillside city of Dharamsala. After weeks of careful preparation, the big day arrived, and I led the group up the mountainside to the Dalai Lama’s residence. As the Dalai Lama proceeded to greet everyone, he paused and stood in front of me.

“Where are you from?” he asked.

“California,” I replied.

He smiled and asked again, “No, where are you really from?”

“Your Holiness,” I said, “Kerala, India.”