Like Father, Like Son: The Francis Ambassadorships

Although John M. Francis and son Charles are not well known, they share an important distinction: Both served as ambassadors—in the same countries.

BY STEPHEN H. MULLER

Over nearly 250 years of American diplomacy, several pairs of fathers and sons (and, more recently, daughters) have served as ambassadors. Occasionally, they have even served as ambassadors to the same country. No doubt the most famous are John Adams and John Quincy Adams in London. The December 2018 Foreign Service Journal carried the story of FSO Ronald Neumann and his father, Robert Neumann, in Afghanistan. Letters to the editor in the June 2019 Foreign Service Journal identified other examples.

But one father and son are truly unique in U.S. diplomatic history: John M. Francis (1823-1897) and son Charles S. Francis (1853-1911) of Troy, New York. They not only served as ambassadors in the same country; they served as ambassadors in the same two countries. John Francis served in Athens from 1871 to 1873, and later in Vienna from 1884 to 1885, while Charles Francis served in Athens from 1901 to 1902 and in Vienna from 1906 to 1910.

Note that I am referring to the Francises as “ambassadors.” The United States did not begin to call the chief of a foreign mission an ambassador until after Charles Francis’ service. Technically, the Francises’ title was “minister,” and they headed a legation, not an embassy.

A portrait of Ambassador John M. Francis, father of Charles S. Francis who later followed in his footsteps.

Wikimedia

Charles S. Francis, circa 1901, when he served as ambassador to Greece, where his father had served 30 years earlier.

Wikimedia

A Family Dynasty

Born in 1823 in the rural community of Prattsburgh, New York, John Morgan Francis began his career in publishing as an apprentice for the Ontario Messenger in New York’s Finger Lakes region. He subsequently became an editor for successively larger newspapers and, in 1846, moved to Troy—at the time, a booming transportation and manufacturing center at the confluence of the Hudson River and the Erie Canal—to become editor and joint owner of the Northern Budget. Five years later, he founded the Troy Daily Times, which became one of the city’s chief newspapers.

Yet Francis’ interests went beyond publishing. According to an obituary, “Mr. Francis became a member of the Republican party at its birth.” He was active in New York state Republican politics, which brought him to the attention of President Ulysses S. Grant and resulted in his diplomatic appointment to Greece in 1871. Following service as minister resident/consul general in Portugal from 1882 to 1884, he was appointed envoy extraordinary and minister plenipotentiary to Austria by President Chester A. Arthur in July 1884.

Born in Troy in 1853, Charles S. Francis would follow in his father’s footsteps, literally and figuratively. He became proprietor of the Troy Daily Times on his father’s death in 1897. And after serving as his father’s secretary in Athens and Vienna, he returned to diplomatic service when President William McKinley named him minister to Greece in 1900. President Theodore Roosevelt named him ambassador to Austria-Hungary in 1906.

During their assignments in Greece and Austria, the Francises dealt with many usual and some unusual matters of the day. The following snapshots of their diplomatic work are drawn from excerpts of official communications out of Vienna and Athens contained in the volumes of the U.S. State Department publication, Foreign Relations of the United States. All communications from an embassy go out over the name of the ambassador regardless of the author, so we cannot be sure if all the passages quoted were written by one of the Francises. But given that both were in the newspaper business, it seems likely that they wrote their own diplomatic cables.

Navigating Religious Controversy

While serving in Vienna, John M. Francis supported the U.S. government’s official anti-Mormon policy of the 1880s. The international aspect of this policy was to discourage immigration by Mormons recruited overseas. The Austrian government was sympathetic. In a series of approving cables in 1884, Francis described measures that had been adopted by Austria “for the repression of Mormon proselytizing and recruiting in His Majesty’s Empire for the purpose of securing accessions by emigration to the polygamous sect in the United States.”

He also reported that Thomas Biesinger of the Utah Territory, chief agent of the Mormons for Austria, had been arrested in Prague and sentenced to one month’s imprisonment and a fine of five florins “for encouragement of a religious creed not sanctioned by the state.”

Given that both [Francises] were in the newspaper business, it seems likely that they wrote their own diplomatic cables.

The Austrian government pointed out that Mormon proselytizing and recruitment were violations of Austrian laws that prohibited organized methods of inducing people to emigrate, and that it had instructed all regional governments “to keep a watchful eye upon them and to issue such orders to their subordinates as would suppress all possible recruiting for the Mormons by all lawful means.”

Francis praised the Austrian position, telling Foreign Minister Count Szogyényi: “I am instructed by my Government to recognize the action referred to of His Majesty’s Government, and to express its sincere gratification that such praiseworthy action has been taken.”

In late 1901, Charles S. Francis described the violence that ensued in Athens following a seemingly innocuous event: the translation and publication of the Bible into common (“vulgar”) Greek. Although this project had been approved by the Metropolitan (the head of the Greek Orthodox Church), “expressions were employed by the translators, which the Hellenes regard as unfit to be printed in the Holy Scriptures.” As a result, “Athens has been the scene of mob demonstration which … almost assumed the proportions of a revolution,” Francis reported.

He continued, “Mass meetings were held in front of the university buildings on the afternoons of November 19 and 20, at which violent speeches were made in denunciation of the objectionable biblical translation and of all those identified with it.” Opponents of the project, led by university students and labor unions, called for a mass demonstration; the Greek authorities unwisely reacted by mobilizing military forces in the capital.

“Late in the afternoon the expected collision took place between the authorities and the aroused Athenians. The mob, now numbering over 25,000, proceeded to the ministry of finance and demolished the windows of the building. Thereupon, shots were fired upon the crowd by police officers and employees of the ministry. The rioters responded with pistols and stones and were only dispersed after a cavalry charge and several carbine volleys,” Francis wrote.

Eight demonstrators were killed and more than 60 wounded. “That the casualties were not greater may be explained by the fact that the soldiers were unquestionably in sympathy with the sentiments of the rioters, and did not direct their fire upon the crowds, the effective shooting being done by the police or gendarmes.” After these events, the Greek government and church capitulated. Two senior police officials were sacked, the Metropolitan resigned; and, as Francis reported, “Priests read from every pulpit in Athens a [religious] decree … which prohibits, on pain of excommunication, the sale or reading of any translation of the Bible.”

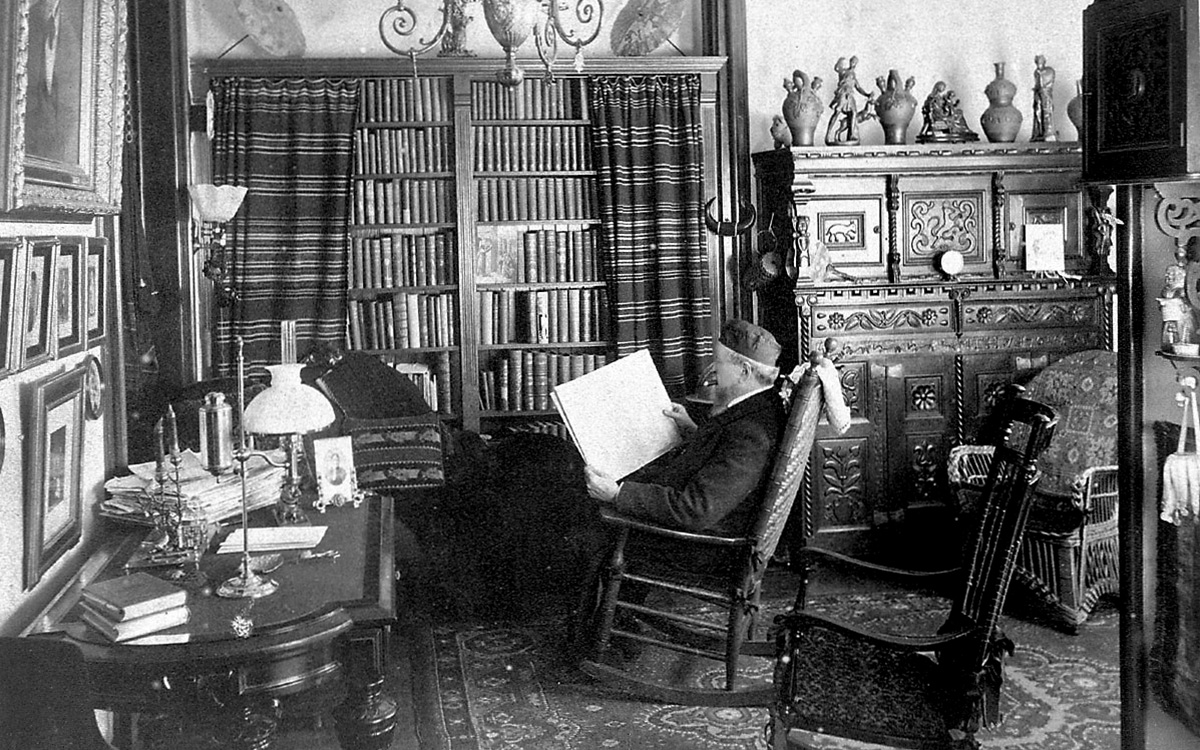

John M. Francis in his Troy study, 1889.

Hart Cluett Museum, Troy, N.Y.

Protecting U.S. Citizens and Promoting Exports

Protection of citizens overseas has always been a priority of U.S. embassies. One particular issue facing naturalized U.S. citizens returning to Europe during the Francis ambassadorships in the late 19th and early 20th centuries was conscription into the armies of their birth countries. Many European armies were based on universal conscription, and some governments did not, as a matter of principle, recognize foreign naturalization as an exemption from conscription.

This was such a serious issue for Greece and Austria that in 1901 the State Department instructed the embassies in both countries to warn naturalized U.S. citizens that naturalization was not an automatic exemption from conscription. The instruction to Athens said: “The Greek Government does not, as a general statement, recognize a change of nationality on the part of a former Greek without the consent of the King, and a former Greek who has not completed his military service and who is not exempt therefrom under the military code may be arrested upon his return to Greece.”

Charles S. Francis dealt successfully with at least one such case in each country where he served. In Greece, he secured the release of Louis (Leonidas) Economopoulos from the Greek Army in 1901, but it took two years of diplomatic struggle. In 1906 Francis similarly secured the discharge from the Austrian Army of Peter Szatkowski.

Unfortunately, he was not as successful in opening the Austrian market to U.S. meat exports, particularly of salt pork. A long series of cables from 1906 to 1908 describe U.S. efforts to get salt pork exports accepted by Austria, and the reasons why Austria refused. The fundamental issue was a dispute over sanitary standards; these kinds of disputes persist to this day between the U.S. and the European Union.

This was also a situation in which the embassy had no independent expertise and was basically relaying messages between the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the Austrian authorities. The Austrians insisted that a “certificate of microscopial inspection” accompany shipments of salt pork, while the USDA said it had discontinued this inspection because it believed the salt curing effectively killed trichinosis. The Austrians said that U.S. meat imports were already treated more favorably than imports from European countries; and furthermore, they had found trichinosis in some U.S. salt pork. The fact that Upton Sinclair’s exposé of the U.S. meatpacking industry, The Jungle, came out while this bilateral debate was going on probably did not help Francis’ case; the Austrians referred obliquely to the book in one of their communications.

Reporting

The Charles S. Francis family, 1893.

Hart Cluett Museum, Troy, N.Y.

Another major function of embassies is to keep the State Department informed of major developments in the host country and the status of bilateral relations. Both Francises fulfilled these obligations.

During the Greek elections of early 1873, the second within the space of a year, John M. Francis reported that the results were favorable to incumbent Prime Minister Deligeorgis, who was popular with the electorate for resisting demands from France and Italy. He further commented that this election was “the most quiet one that has occurred in Greece in many years. The only disturbances thus far reported took place at Messenia, where, it is said, three murders were committed, and at Zirochori, in Euboea, where mob violence prevailed to some extent; but these districts embrace disorderly elements that always appear in more or less tumultuous proceedings on election occasions.”

In May 1873 Francis set out on a brief tour of Greece, “deeming it desirable to acquaint myself by personal observation with the resources and capacities of the country outside of Athens.” He was accompanied by son Charles, as well as a New York congressman, an interpreter—and an escort of soldiers.

He reported on well-tended vineyards, olive groves and fields of grain, but noted the Greek “adherence to agricultural implements of the patterns used in the time of Homer.” He also remarked that Greeks had begun to cultivate cotton in response to the scarcity caused by the U.S. Civil War. He said all the villages he visited had schools for boys, but only one had a school for girls. He commented that he was received warmly by Greeks everywhere, who expressed “gratitude to the American people for aid and sympathy to the Greeks in the hardships of their revolution.”

Charles S. Francis encountered the same warmth from Greece during his subsequent tour there, when President William McKinley was assassinated in 1901. He conveyed this message of sympathy from the Greek foreign minister to the State Department: “The sad news of the death of the President of the United States, victim of an odious crime, has caused the Royal Government profound feeling; and therefore, in its name, I pray you to accept my sentiments of keen sympathy. Greece joins in the profound sorrow which the people of the United States of America suffer on this sad occasion.”

The European squadron of the U.S. Navy visited the port of Piraeus in 1902. “The visit of the American war ships to Greek waters elicited much favorable comment,” Francis reported. The fleet admiral and his officers “were the recipients of marked social attentions during their stay here.” They were formally presented to the king and queen, who in turn visited the fleet’s flagship.

John M. Francis and Charles S. Francis may not rank among the more notable American ambassadors (but by all measures they performed their duties competently). They are, however, unique in having served in the same places, albeit at different times.

Read More...

- “Working to Strengthen U.S. Diplomacy,” interview with Amb. Ron Neumann, The Foreign Service Journal, December 2018

- “Speaking of Father-Son Ambassadors,” John Treacy, The Foreign Service Journal, June 2019

- “Seldin Chapin: Father of the 1946 Foreign Service Act,” by Jack R. Binns, The Foreign Service Journal, February 2011