Working to Strengthen U.S. Diplomacy

The recipient of AFSA’s 2018 Lifetime Contributions to American Diplomacy Award talks with the FSJ about his career at the center of some of America’s toughest foreign policy challenges.

Ambassador Ron Neumann with his wife, Elaine, in Gor, Afghanistan, 2006.

Ronald E. Neumann received the American Foreign Service Association’s 2018 Lifetime Contributions to American Diplomacy Award at an Oct. 10 ceremony in the U.S. Diplomacy Center at the State Department. (For coverage of the ceremony, see AFSA News, p. 69.) He is the 24th recipient of the award, given annually in recognition of a distinguished practitioner’s public service career and enduring commitment to the professional Foreign Service and to diplomacy.

Born in Washington, D.C., on Sept. 30, 1944, Ron Neumann grew up in California and France. He earned a B.A. in history and an M.A. in political science, both from the University of California at Riverside. Prior to joining the Foreign Service in 1970, Mr. Neumann was an Army infantry officer in Vietnam, where he earned a Bronze Star, Army Commendation Medal and Combat Infantry Badge.

His first Foreign Service assignment (1971-1973) was to Dakar as a rotational officer in the consular and commercial-economic sections—a posting that included a three-month stint as chargé d’affaires in Banjul. After that, Ambassador Neumann spent most of his Foreign Service career on regional issues related to the Middle East and South Asia.

After overseas assignments as principal officer in Tabriz (1976) and deputy chief of mission in Sana’a (1981-1983) and Abu Dhabi (1987-1990), Amb. Neumann served three times as chief of mission: in Algeria (1994-1997), Bahrain (2001-2004) and Afghanistan (2005-2007). He may well be the only threetime ambassador whose father was also a three-time chief of mission, though Robert Neumann’s postings were all political appointments: to Afghanistan, Morocco and Saudi Arabia. (The only other father-son pair of ambassadors to serve in the same capital are John Adams and John Quincy Adams; both served as ministers to Britain.)

From 2004 to 2005, immediately before his posting to Kabul, Amb. Neumann also served in Baghdad with the Coalition Provisional Authority, and then as the embassy’s political/military liaison with the Multi-National Force–Iraq, where he was deeply involved in coordinating the political part of military actions.

In Washington, his assignments included: political officer in the Office of Southern European Affairs (1976-1977), staff assistant in the Bureau of Near Eastern Affairs (1977-1979) and Jordan desk officer (1979-1981). Later in his career, he was director of NEA’s Office of Northern Gulf Affairs, responsible for relations with Iran and Iraq (1991-1994), and an NEA deputy assistant secretary with responsibility for North Africa and the Arabian Peninsula (1997-2000).

Following his retirement from the Senior Foreign Service in 2007, Amb. Neumann became president of the American Academy of Diplomacy, a position he continues to hold today. In that capacity, he leads an ongoing effort to strengthen U.S. diplomacy, including both the Foreign Service and Civil Service, and enable their members to effectively develop and carry out U.S. foreign policy by upgrading their professional formation. Toward this end, AAD has issued a series of seminal reports, including “American Diplomacy at Risk” and “Support for American Jobs.”

Amb. Neumann serves on the Advisory Committee of the School of Leadership, Afghanistan, a nonprofit school for girls, and on the Advisory Board of Spirit of America. He is also on the board of the Middle East Policy Council and on the Advisory Council of the World Affairs Councils of America.

The author of The Other War: Winning and Losing in Afghanistan (Potomac Press, 2009) and Three Embassies, Four Wars: A Personal Memoir (XLibris, 2017), Amb. Neumann has published numerous op-eds, monographs and articles on Afghanistan and other foreign policy topics. He speaks Arabic, Dari and French. He received State Department Superior Honor Awards in 1990 and 1993; and for his service in Baghdad, he was awarded the Army Outstanding Civilian Service Medal. He is married to the former M. Elaine Grimm. They have two grown children.

Amb. Neumann has made a major contribution to strengthening the professional Foreign Service. He is a natural choice for this award.

FSJ Editor Shawn Dorman conducted the following interview with Amb. Neumann in October. Photos are courtesy of Amb. Neumann.

FSJ: I understand you decided to apply to the Foreign Service while you were still in high school. Did your father’s experience as ambassador to Afghanistan shape that choice, or were other factors involved?

Ronald E. Neumann: My father was still a university professor when I decided on a Foreign Service career. However, he had many foreign contacts who sometimes visited the house, as well as some Foreign Service officers. Somehow, these contacts lit my desire to become an FSO.

Later my father became an ambassador. He was a Republican who supported Lyndon Johnson against Barry Goldwater, whom he found too extreme. The result was that he ended up being nominated as ambassador to Afghanistan by Johnson, staying there under President Richard Nixon, going as ambassador to Morocco under President Gerald Ford and then, after being out during the Jimmy Carter years, being appointed ambassador to Saudi Arabia by President Ronald Reagan. He was thus fairly unique; a political appointee who served four presidents, three embassies and two parties.

Lt. Ron Neumann heading out on patrol in Vietnam, 1969.

FSJ: What was it like having a father who was a three-time ambassador?

REN: I entered the Foreign Service while he was still in Afghanistan. Our joke was that we entered the FS at much the same time; he at the top and I at the bottom. I first saw an embassy, as it were, through the ambassador’s eyes, when my wife and I spent three months in Afghanistan after graduate school. That experience was a huge aid when I finally got into the Foreign Service. I had some understanding of what an ambassador wanted, how to work with a deputy chief of mission (DCM), and so on. The downside was that I didn’t fully experience the emotions or strangeness of being an entry-level officer. Later, when I supervised entry-level officers, I had to get the experience vicariously, intellectually, to properly understand what they were going through.

FSJ: How did your time in the Army during the Vietnam War prepare you for a Foreign Service career?

REN: I served as an infantry rifle platoon commander with some 30 to 40 men under my charge (our strength varied depending on casualties, health and replacement rates), and later I was the company executive officer. I learned a lot about managing people and administration in general. Also, the Army has some very effective ideas about leadership that have served me well. One of the most important was that discipline depends on loyalty, and that loyalty only exists if it is two-way—from the top down as much as the other way. Those who try to demand loyalty without returning it deserve the disappointment they usually get.

FSJ: What year did you take the Foreign Service Exam? What was the process like then?

REN: I first took the written exam in 1965 (I think) and did not pass. I took it again the following year, more successfully. I don’t remember much about it. The oral seems to have been a bit more “free form” than what I hear described nowadays.

FSJ: When did you join AFSA?

REN: About two years after I became an FSO, as nearly as I remember. Initially, I had the idea that the Foreign Service would be a sort of mannerly club, so why did one need a union? I learned that while it is an impressive service it is also a bureaucracy that sometimes doesn’t treat people with fairness. It took me about two years to figure this out, and I then joined AFSA.

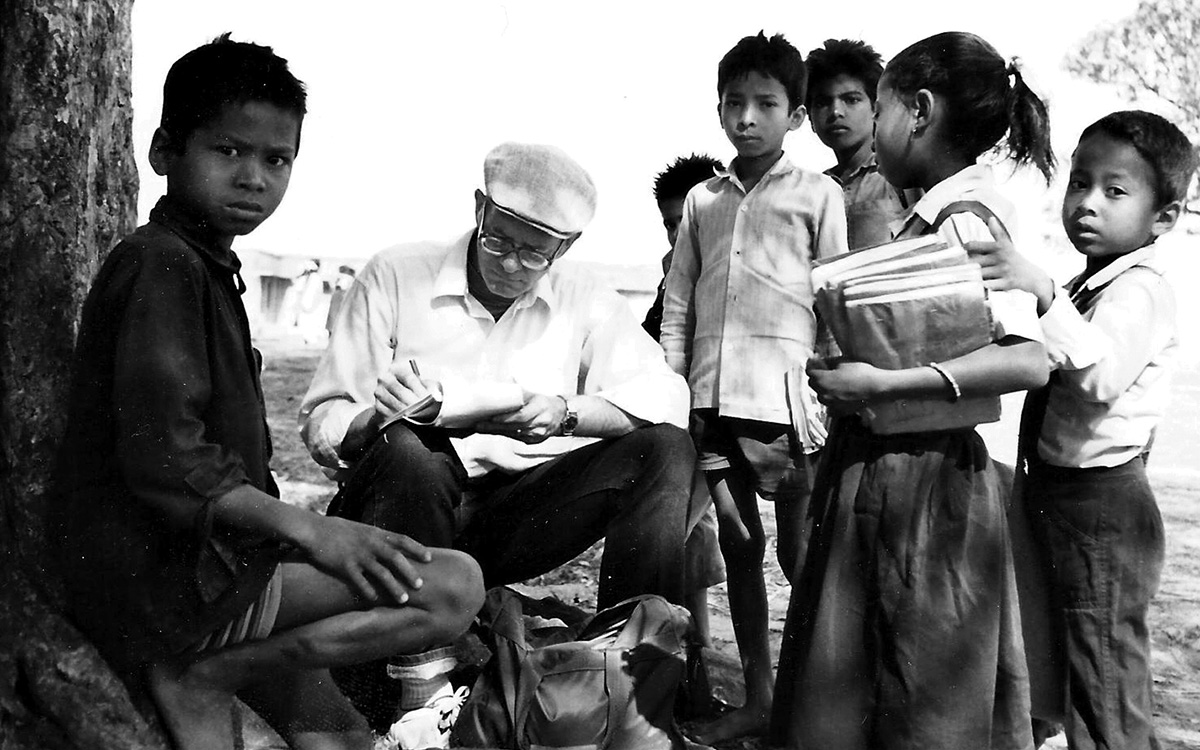

Ron Neumann making notes in his journal in Nepal, 1987.

Your Career

Ron Neumann, with Elaine Neumann holding the Bible, is sworn in by Secretary of State Colin Powell, as U.S. ambassador to Bahrain in 2001.

FSJ: Your first Foreign Service posting was to Senegal in 1971. Was that posting a good introduction to the Service for you? How?

REN: Dakar was a great tour. I had six months as the only consular officer, and then became the only economic officer at post. Shortly after the change, the chargé in Bathurst (now Banjul) in The Gambia died. His widow, in shock, couldn’t make up her mind whether to bury him in The Gambia or send his remains back to the United States. It was summer in West Africa, Bathurst had no mortuary facilities, and a decision was needed. I ended up driving an undertaker and a coffin from Dakar and helping to seal up the coffin, and then was made chargé in Bathurst for three months until the department could find a properly senior officer to replace me.

The post consisted of me and one local clerk, plus a driver and house staff. I was the admin officer, the cashier and the one to seal pouches and meet the courier at the airport. I also lobbied the Gambian president for his United Nations vote, wrote the cable and encrypted it. There were no clearance issues at a one-person post! I spent a lot of time reading the Foreign Affairs Manual, and I learned a major amount about State Department regulations, administration and paperwork. In short, it was a superb introduction to all sorts of Foreign Service work.

The ambassador, with the assistance of the country team, has a major role to advise on what will and won’t work and how to shape policy execution.

FSJ: You spent the bulk of your career in the Middle East. What made you decide to concentrate on that part of the world?

REN: I had a 3 1/2-month break between graduate school and reporting for the army. My wife and I stayed with my parents in Afghanistan and traveled all over the country. That was where I developed a strong interest in the Muslim world and decided to specialize in that part of the world.

FSJ: What were some of the opportunities and challenges you encountered working in the Middle East? Are you optimistic about prospects for peace in that region?

REN: I found many wonderful people and friends in the Middle East and Afghanistan. Radical Islam is contesting to set many areas back, and corruption and poor governance have given the radicals an opening; but many within Islamic society oppose them. These fluctuations need to be worked out within the countries themselves; and I say countries because, while the Islamic State or al-Qaida are transnational movements, the pushback against them and the societal solutions are national.

I am not optimistic about Arab-Israeli peace, however. Neither side has the leadership necessary.

FSJ: If you could, please share your personal opinion on what the U.S. should be doing about the conflict in Yemen today, on the right U.S. approach to Iran and on the current U.S. approach to the Middle East.

REN: These are giant issues that need more than sound-bite answers. On Yemen, we do need to push for a negotiated solution, but Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates are countries that are important to us. I think it would be easier to wreck our relations than to force them to solutions they don’t want. So we’ll have to work very carefully with diplomacy, with some pressure, and with a great deal of realism.

I disagreed with our withdrawal from the Iran nuclear deal. Now we have a situation where each side is so suspicious of the other that any new negotiation is going to be even tougher than the last one; and that took years. I think I’ll stop there, because these issues really need discussion that is more nuanced than we have time for here.

FSJ: You served in many different countries and capacities over the course of your 37-year FS career. Which of your postings stand out the most in your memory, and why?

REN: Iran was a wonderful tour. There were only two of us; we covered about 20 percent of the country, and there was a lot to report on. Algeria was my first ambassadorship. There was an insurgency and a blanket death threat against all foreigners, so we lived on the compound but developed a lot of ways to make contacts. It was very challenging, not least because of Washington pressure to cut the post more than I thought wise. But I was and remain very proud of the work we did. I had a great staff, including Robert Ford, a brilliant officer.

FSJ: Is it fair to say that your work in Iraq with the Coalition Provincial Authority was unique compared with all the rest of your Foreign Service assignments? How did you approach it?

REN: In Iraq the CPA was unique, because as the occupying power we were governing the country. That is almost a throwback to being a colonial power, except that we wanted to leave and to do so quickly. Yet at the same time many in Washington and CPA wanted fundamentally to change the political structure, and even the political culture, of the country. I don’t think we reflected much, if at all, on how contradictory these goals were.

We made a lot of mistakes, and a lot has been written about them. I was a sort of utility diplomat for Ambassador Paul Bremer. My post was director of the Foreign Ministry, and I was fortunate that I had a longtime association with Iraqi Acting Foreign Minister Hoshyar Zibari. However, I took on a variety of tasks. Early on I worked on negotiating a memorandum of understanding between State and the Defense Department for the management of police training (then-Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld subsequently overturned it). At one point I worked on making sure our people in Najaf were supported during the Shia uprising. I did a lot of work with the Kurds. I had known many of the Kurdish leaders when I served in Iran, and they came in as refugees after the collapse of the 1974 uprising against Saddam. Then I worked with them again when I was director of the Iran-Iraq office at the State Department.

One very frustrating experience concerned trying to set up a foundation with $100 million to get Kurds, Arabs and Turkmen in Kirkuk to work together. This was the brilliant idea of Emma Sky, who knew Kirkuk well. It might not have solved all the problems, but it would have given the different communities reason to cooperate. It’s too long a story for all the details here, although I tell it in my autobiography, Three Embassies, Four Wars: A Personal Memoir. But the bottom line was we got everything done and had all the communities on board. But then, because nobody told Emma or me of the secret decision to transfer sovereignty to Iraq two days earlier than planned, the transfer of $100 million was rejected by the Federal Finance Bank in the United States as being too late by four hours; we no longer controlled the money. The foundation never came into being.

I stayed on for another year after the CPA ended and worked with our military a lot. It was fascinating work despite some risk. We tried to accomplish a lot, but the instability set loose by the overthrow of Saddam Hussein will take years to settle down.

At AAD we are embarking on a new study of areas for managerial improvement in the department, including a fresh look at some problems for FS specialists and Civil Service personnel.

FSJ: You were chief of mission three times: to Algeria, Bahrain and Afghanistan. Could you tell us a little about each posting?

REN: I mentioned a few things earlier about Algeria. In Afghanistan, about which I’ve written a book (The Other War: Winning and Losing in Afghanistan), we could see that the war was going to get worse. We were terribly under-resourced, but Iraq was sucking up most of the resources. I think we did some good work, and our predictions still stand up well; but we lost a lot of time for lack of resources.

Bahrain was just beginning some important political reforms. With the help of the National Democratic Institute and a lot of patient work, I think we helped move things in a positive way, at least at that time. We spent much of two years bringing about negotiations for a free trade agreement, which was signed after I left. Getting there was, perhaps, the most complicated bureaucratic maneuver I’ve ever designed (in partnership with Cathy Novelli, who was then at the Office of the United States Trade Representative).

FSJ: What do you see as the most important role of an ambassador, chief of mission?

REN: The U.S. government has a lot of different interests. Washington is too large to ever coordinate all the pieces in a bilateral relationship, so the ambassador has a very important role in coordinating all the aspects of policy. And an activist ambassador can play a very strong role in advocating policy; it’s not just about observing and reporting. With the assistance of the country team, the ambassador plays a major role by advising on what will and won’t work and how to shape policy execution. Additionally, an ambassador is really like the mayor of a small town, with all sorts of responsibilities for morale and, above all, for the security of mission personnel and Americans in the country. There’s lots more, but that’s probably enough for now.

Ambassador Ron Neumann, second from right, dedicating U.S. Embassy Kabul in 2006 with, from left, Laura Bush, President George W. Bush, Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice and Afghan President Hamid Karzai.

Afghanistan

FSJ: You first lived in Kabul more than half a century ago, when your father was ambassador, and you’ve been back many times since. What do you find so fascinating about Afghanistan?

REN: Afghanistan was pretty exotic when we first traveled there in 1967. We drove back roads across the center of the country. I went with a hunting party by jeep, horse and yak into the high Pamirs of the Wakan, the panhandle of northeastern Afghanistan. That was pretty heady stuff at age 22. And the Afghans are an attractive people, although that’s true of many countries. Also, my father was ambassador there for 6 1/2 years and remained active in Track II diplomacy throughout the Soviet occupation period. He and I frequently discussed the situation. Whether all those bits actually explain my attraction I can’t say. I guess it’s become a family thing.

FSJ: How would you compare the war in Afghanistan with the one in Vietnam? Are you optimistic about prospects for some sort of modus vivendi with the Taliban?

REN: There are similarities and big differences between the two wars. Militarily the Taliban is not much like the Viet Cong or the North Vietnamese Army that sent regular military units into full-scale battles with thousands of casualties. The VC and NVA were far more unified than the Taliban, their international backing much larger. Where I see a distressing similarity is in the corruption and power-seeking of the Afghan politicians. There are many reasons for this, but if an Afghan national leadership can’t develop a real popular base, and particularly can’t develop an efficiently commanded Afghan army and police, then they will not be able to stand up to the challenges that face them.

FSJ: Something that came out of Afghanistan, but is perhaps better known for its application in Iraq, is the provincial reconstruction team (PRT) mechanism. Did your experience overseeing PRTs while serving with the Coalition Provisional Authority in Baghdad influence your use of them during your subsequent tenure as chief of mission in Kabul? Should the U.S. government continue using PRTs in conflict or post-conflict zones?

REN: PRTs were in Afghanistan when I arrived, but were not used in Iraq until after my time there. The situation in the two countries was different. In Iraq there were local government arrangements and personnel, and the task was to help them become more efficient. When PRTs began in Afghanistan, there was no provincial government. It had been completely destroyed by years of war. The PRTs were initially a stand-in for a nonexistent local government; flawed perhaps by being foreign, but also the only way to deliver any aid to a distressed population. As the Afghan government grew, the challenge changed to how to diminish the PRTs’ role as a parallel government, to help the real one, and then for us to go away. Each of these phases had its own problems.

There may be occasions in the future where we will need this mechanism. If we do, I hope we will understand that we’re not very good at standing in for other people’s government. We don’t have the detailed expertise; and while our money will be welcome, our authority won’t. So I hope we’ll keep our expectations in check.

Ambassador Ron Neumann, standing middle, with U.S. Special Forces at Spin Boldak on the Afghanistan-Pakistan border, 2006.

Diplomatic Readiness Today

American Academy of Diplomacy President Ambassador Ron Neumann, left, moderates a Q&A session with Ambassador Joyce Barr and Ambassador William Brownfield, 2018 inductees to the National Defense University’s Hall of Fame.

FSJ: Under your leadership, the American Academy of Diplomacy has consistently advocated for more resources to be devoted to professional training for the Foreign Service. How would you assess the state of diplomatic readiness and the profession today?

REN: The training has improved, but diplomatic readiness overall is weaker. On the training and education side, the resources have never been made available to do much of what multiple studies have called for. Nor has the State Department made professional education a requirement in anything like the way the military has. And over the last year, we have lost many experienced officers. So I’m looking at the combination of teaching and experience when I conclude that we are weaker.

FSJ: The “American Diplomacy at Risk” report raised many problems and offered suggested solutions to “save” the Foreign Service. Two years later, how do you see that report and its impact?

REN: A few pieces of it have been implemented. Many have not, although the report continues to be quoted and referenced in many other reports. It is useful to remember also that many of the issues we raised have been around for some time.

FSJ: What are you working on currently at AAD?

REN: We have two new podcast series going: “The General and the Ambassador” and “America’s Diplomats.” Both are designed to help Americans understand more about what diplomacy is and does. We are also partnering with the McCain Institute to produce scenarios to teach ambassadors and DCMs how to think through difficult and long-running security issues. This is a critical area that the State Department has never addressed in its training. We will turn the finished product over to the department at no charge. We hope they will make use of it.

Finally, we are embarking on a new study of areas for managerial improvement in the department, including a fresh look at some problems for FS specialists and Civil Service personnel.

FSJ: How do you see AAD’s role in terms of advocacy?

REN: We reach out within our capacity to Americans to talk about the value of diplomacy and what it is all about. With the department, we advocate measures to strengthen and make diplomacy more effective; but we are not AFSA, and generally stay out of strictly Foreign Service issues. With Congress we advocate for proper funding for diplomacy. In one case we advocated against a nomination which, we felt, was contrary to professional diplomacy.

FSJ: Does AAD ever take positions on policy issues?

REN: Not as an organization, although many individual members take positions on policy issues.

The Foreign Service Career

Under Secretary for Political Affairs David Hale presents AFSA’s Lifetime Contributions to American Diplomacy Award to Ambassador Ron Neumann on Oct. 10.

FSJ: What are the essential ingredients for a successful diplomat?

REN: There are probably as many answers as there are diplomats. One essential is listening well, so that you know how to shape your own arguments for maximum success. Another is to master your home bureaucracy, so that you know how best to advocate for policies you believe in. Few things are more prone to ridicule and ineffectiveness than a diplomat who is tone deaf to his or her own nation’s politics. This does not mean that one should not advocate for unpopular policies; but, rather, that one must know how to shape the argument. Clear and precise writing is essential. Those are a few things that I would pick out, but there are whole books written on this subject.

FSJ: Who were some of the people you especially admired or were inspired by during your Foreign Service career?

REN: I have had so many mentors and guides that it is difficult to pick out a few. Certainly my father was one. We were colleagues and friends, as well as father and son. Hal Saunders was another, as I mentioned in my remarks on receiving the award. I have learned from every ambassador for whom I have worked— from Ed Clark long ago in Dakar to John Negroponte in Iraq.

FSJ: How would you describe Civil Service-Foreign Service relations, and what changes have you seen over time?

REN: The Civil Service has become a much more crucial part of the conduct of diplomacy than it was when I entered the Foreign Service. The department has to manage three personnel systems: Foreign Service, Civil Service and Locally Employed staff. There are many structural rigidities in the systems that cause strains between the Civil and Foreign Service. These problems weaken our diplomacy overall. There are also longstanding problems that affect the specialists within the Foreign Service. AAD is beginning a new study to suggest some solutions in these areas. We hope the department will consider what we put forth.

FSJ: How successful has the Foreign Service been in increasing diversity? Should that be a priority? How can the foreign affairs agencies retain minority talent once those individuals are in the Foreign Service?

REN: The State Department has been trying hard to increase diversity, but still faces problems. Recently it has lost too many highly qualified officers at the senior level, including a disproportionate number of diversity officers. Recruitment of diverse candidates is starting to pick up again, but a number of problems remain at the senior level.

FSJ: How would you describe the state of the Foreign Service as an institution today?

REN: The Foreign Service is troubled as an institution. There is a sense—whether justified or not—that there is a suspicion of professionals, not only in the Foreign Service but across the government. The appointment of David Hale as under secretary for political affairs is a praiseworthy exception, but I am told that we are unlikely to see any more serving senior officers appointed to senior positions in the department. An institution which is visibly distrusted is bound to suffer doubts. Nevertheless, the Foreign Service is full of dedicated individuals, determined to serve the nation. I believe it will come through this difficult period as it has done in difficult periods in the past.

FSJ: How has the role of the Foreign Service changed?

REN: The explosion of Cabinet agencies working abroad has led to a diminution in State’s lead role in the formulation of policy. Many factors have gone into this, including the fact that we now deal with many issues —from trade to climate—that have major domestic implications. One cannot make foreign policy without taking into consideration domestic policy, although if one only looks at domestic issues the result may be bad foreign policy. Some of this can be improved, but it cannot happen by law or executive decree. State will have to earn back a leading role through the quality of its work. This is much too large a question to be answered in a paragraph, but adequate staffing, budgets and professional education are all part of the answer.

During 37 years in the Foreign Service I often went home at night with frustration about this or that decision. But never once did I go home and wonder if what I was working on mattered.

FSJ: What advice do you have for active-duty diplomats who may feel that diplomacy has been sidelined in recent years as military power and political expediencies take center stage?

REN: Diplomacy remains indispensable. That is the nature of the problems we face today. The limits of military solutions are clear—particularly to our own military, who are well aware of the need for partnership in policymaking and execution. I believe this reality and the general tiredness of Americans with long-lasting wars will bring diplomacy back to the fore. Diplomats should not lose hope. Their services will continue to be needed. Frustration is understandable. Despair is not.

FSJ: Are you discouraged or optimistic for the future of the Foreign Service and professional diplomacy?

REN: I am optimistic. That is a basic requirement of diplomacy, or the immensity of the challenges we confront would overwhelm us. America needs its best men and women in the diplomatic service, whether as Foreign Service officers and specialists or in the Civil Service. Whenever I am asked, I continue to urge people to join, to get into the game. No problem was ever solved by sitting on the sidelines and complaining.

FSJ: How do you see AFSA’s role?

REN: AFSA is both a professional organization and a union. Both functions are essential, but there is always going to be tension between them. AFSA has done an outstanding job of pushing for and defending a better budget in the Congress. They, and particularly AFSA President Barbara Stephenson, deserve great credit for what they have accomplished.

FSJ: What would be your advice to college students and recent graduates seeking to enter the Foreign Service or government service more generally?

REN: Get in. Work hard. Make a difference. America needs you. Besides, the Foreign Service, about which I can speak the most, offers the chance to do important work with some of the most intellectually impressive and interesting people you’ll ever work with. During 37 years in the Foreign Service I often went home at night with frustration about this or that decision. But never once did I go home and wonder if what I was working on mattered. There are not many careers that offer that.