What Local Staff Want You to Know

Locally employed staff around the world offer their perspectives on working for U.S. missions.

Early in 2018, through AFSAnet messages and networking, we began asking Locally Employed staff/Foreign Service Nationals from around the world to submit stories and advice based on their experiences working with American staff, working for the United States. The purpose was to gain a sense of how local employees see their work and what we can learn from their perspectives— perspectives that may not always be solicited at post. We shared a set of questions widely, suggesting respondents use the questions as a guide but essentially, to tell us what we should know about them in relation to their work and experiences.

We asked the following questions:

- What advice would you give American employees at the embassy about working with local staff?

- How have you in your work contributed to relations between your country and the United States? Please share the story of a time you felt your work made a difference.

- What do you think the U.S. embassy/mission should focus on but isn’t?

- The most interesting thing about my job is…

- The hardest thing about my job is…

We are sharing all 18 responses here, edited lightly for style and clarity. We are so grateful to all those who responded for their thoughtful and insightful comments. Thank you to these local staff members, and to all Locally Employed staff around the world, for your work on behalf of the United States to advance diplomacy, development, prosperity and security.

—The Editors

Engage Your Local Staff Right Away

Helane Grossman

Human Resources Office, U.S. Embassy Paris, France

Helane Grossman.

“When I get to post I plan to innovate and be remembered for my innovation.” What U.S. direct hire hasn’t aspired to this at least once in their career? While making a positive difference naturally goes hand in hand with career advancement for inspired officers, to truly create an enduring success story, make it a team effort with the local employees.

Local employees are institution-builders too, carrying out the daily tasks that enable the managing officer to focus on program management. They represent the continuity of a mission and, as such, will be the ones who continue to carry the torch long after individual supervisors have moved on to other posts.

With this in mind, my advice to U.S. direct hires is to learn to have confidence in their Locally Employed staff by soliciting their input. This may be easier for seasoned career diplomats than for first- or second-tour officers, but it is never too early to try. For example, before laying out your plan for a policy change or a reconfiguration of operations, make inquiries about past efforts by your predecessors. Chances are, one of them had a similar idea! Your local staff is there to provide background, which is of immeasurable value. In fact, the local employees are the eyes and ears of post. Tap into their knowledge. Don’t be blind or deaf to their contributions.

You might be asking yourself how you can put your trust in someone you just met. The easiest and most effective way is to take the time to meet with each of your local employees within the first couple weeks after arriving at post. How they welcome you and your new ideas is largely dependent on your desire to take an interest in them. Try to speak a couple of words in the local language—even if you are in a position that is not language- designated. This first contact will go a long way toward fostering mutual respect between managers and subordinates that will, in turn, pave the way to open communication and a fruitful professional relationship.

Once you have gained mutual confidence, lean on your local staff. Many of them have been at post longer than you have been in the Foreign Service. Showing that you rely on them can go a long way to reinforce the initial trust. Listen to them when they advise you on local labor laws. Empower them to make decisions. You have the final say; but allowing LE staff to take part in decision-making situations adds to their feeling that they are valued by the section and will add dimension to your results.

Finally, I would encourage American officers to be clear from the start as to their expectations of the local staff. Just as the officers must acclimate themselves to the new environment, local staff must adapt to their new managers. It can be easy to assume that local employees don’t need much, if any, guidance, because they are accustomed to management turnover every few years. I am here to tell you there is nothing further from the truth! Our workplace is ever-changing. Share and share alike with all your staff—whether they have three days or three decades of service behind them.

Understanding What the Real Needs Are

Sopheap Chheav

EXBS Program Coordinator, U.S. Embassy Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Sopheap Chheav.

I was born and grew up in Phnom Penh. I started working at Embassy Phnom Penh in 2010 with the Office of Defense Cooperation. I worked for ODC for six years before moving to the Export Control and Related Border Security (EXBS) Program in 2015, and have been there since.

American employees need to understand the local culture because it will help them get along well with local staff. Listen to the LE staff regarding coordination and cooperation between the host government and the United States because they understand their government well. They are also the ones who will stay and work in the embassy for a longer time.

Local staff are the key people who convey the messages between two governments, so the message must be balanced. I have been working as a program coordinator for almost 10 years at the U.S. embassy. I normally listen to requests or suggestions from the Cambodian government, and if there is any training or assistance that I think the U.S. government will be able to provide or help with, I convey this request to the U.S. government. As a result of support from the United States, Cambodia has received humanitarian assistance, mine removal and military and border security assistance.

Recently I have been working with EXBS to build Cambodian officials’ strategic trade control (STC) capacity. STC is relatively new for Cambodia. Even though we have been working with the government since 2007, we did not have a focus on it and did not have dedicated staff for the program. Since I was recruited for EXBS, the importance of strategic trade control has been recognized by the government of Cambodia and they have developed greater knowledge on what export control systems are. I am so proud of the hard work I put into this program for the past three years and the difference it makes for Cambodia to be part of this program in the region. The government now has a very strong commitment to build a strong regional STC system. I have also had a lot of support from the embassy for this program.

I think the United States should continue to provide more support to Cambodia on security, and especially border security, because the country still has a shortage of human resources and equipment at most of its borders.

To help LE staff be even more successful, management teams should listen to the people on the ground and ask for their input before they plan to do something for the country. By listening to them, you will learn and know what is happening, the real situation, and especially what the needs of the host government are.

Handle Delicate Pluralistic Social Threads with Care

Kawthar Janatni

Budget and Resources Manager, U.S. Embassy Rabat, Morocco

Kawthar Janatni.

American employees who have never had the opportunity to visit Morocco prior to assignment tend to base their insights on reports or websites about my country. I advise them to have their own experience with local staff. Morocco is such a diverse environment that one can barely generalize about the country or its people.

Working with local staff can be an interesting experience and provide a direct feel for the culture and local habits. LE staff, like Moroccans generally, are known for their hospitality and sense of sharing. That is one trait of the population that, in my opinion, helps facilitate the integration of foreigners, and Americans in particular, into their social circles.

Historically, Morocco has been considered an open country in the region and a strong strategic ally of the United States. Its openness to foreign cultures, languages, religions and ethnic groups has been developed over time. That is why it is such a rich environment, preserving its traditional traits and at the same time scaling up on modern lifestyles.

A second piece of advice is that Americans should handle the delicate pluralistic social threads in Morocco with care. Moroccan culture is so different from the individualistic American way of living. The personal space “American bubble” has no existence in the Moroccan social code. What can be perceived as trespassing by an American can be perceived as unfriendliness by a Moroccan.

One would hope that Americans use the pluralistic culture to build a successful professional network that makes everyday operations run smoothly. American staff should occasionally participate in local festivities and dress like a Moroccan for traditional holiday celebrations with local staff. Think about sharing your homemade dishes at potlucks or holding a cookie exchange on arrival, for example; sharing food will be very well received, and will help you integrate quickly into the community.

Local staff represent the continuity of a mission and, as such, will be the ones who continue to carry the torch long after individual supervisors have moved on to other posts. —Helane Grossman

It is also important to note that in Morocco—unlike the way professional structures are managed in developed countries— personal recommendations overrule any other type of advanced referral mechanism. It is referred to as the “Arab phone” in Morocco, meaning that most information is conveyed verbally instead of by written media. Now, however, the practice is shifting toward social media as a modern way of communication.

The notion of time in Morocco is also different from that in the United States. The whole system observes its own timeline, with a more relaxed way of doing business. Expect nonconformity in schedules and unpredictable engagements, and allow some flexibility in dealing with local procedures. From the perspective of LE staff, time is important in building good rapport and strong networks. This can be challenging to American personnel because they are on two- to three-year tours that do not allow a long-lasting experience, so it is up to the local staff to maintain continuity. To overcome this challenge, Americans might save time by getting involved in community events on arrival. For example, it would be interesting to organize icebreaker events for new families at post that include LE staff.

Overall, my advice about working with local staff is to get interested in the culture prior to arrival, but also get involved in your own experience at post for a more interesting and long-lasting relationship with the local population. Culture is the main bridge to link up two different worlds, and if it starts on a solid base it sets the way for a very secure and lasting interaction. The level of integration in local culture makes a big difference in corporate performance.

I am honored to be part of the Women Mentoring Program at Embassy Rabat. It is a group of female direct-hire Americans, paired with Moroccan LE staff. The program not only provides a forum to discuss women’s issues in the workplace, but is also a cultural bridge—for American and Moroccan women to get to know each other better, and for everyone to get to know new people in different sections or agencies at the embassy and stand as one team. Empowerment is the key to success. I think U.S. culture is more advanced in this respect than the Moroccan way of doing business.

FSNs Can Do Even More

Melanie McGovern

Criminal Fraud Investigator, Regional Security Office, U.S. Consulate General, Montreal, Canada

Melanie McGovern.

Not all criminal fraud investigators (CFIs) and Foreign Service National investigators (FSNIs) are retired generals or police chiefs. Just as the Diplomatic Security Service hires special agents from a pool of people with diverse backgrounds and experience, its Locally Employed staff reflects the DSS emphasis on drawing from a wide range of skills and expertise. For example, in Canada, the greatest need of an FSNI or CFI isn’t necessarily to make a midnight call to the chief of police, but to be able to thoughtfully and diplomatically articulate mission goals to our partners and stakeholders.

Through relationships cultivated with our Canadian partners over 15 years, I worked with the DSS resident offices located along the U.S.-Canadian border (St. Albans and Buffalo Resident Offices) to found and develop Operation Northern Watch, an ongoing interagency visa fraud investigation into the misuse of U.S. nonimmigrant visas to cross the U.S. border into Canada for the purpose of claiming asylum.

As a CFI in Canada, I get exposure to a wide range of investigations because a travel document facilitates most international and organized crime. I never expected to develop the type of expertise that I have in seeing the “bigger picture” in any criminal act. Most other agencies focus on the specific crime in front of them, whereas DSS looks at crime from a macro perspective. I get to work with people around the globe, and my competencies grow exponentially when opportunities arise to physically meet with my counterparts.

It would be helpful to train new CFIs like DS agents headed to their first field office tour by letting us tag along with new arrivals for a weeklong training session. That way we can learn the basics of opening a case, filing pre- and post-arrest documents, interviewing, surveillance, U.S. court procedures, etc. CFIs hired from outside of the consulate’s consular section would also benefit from taking the basic consular course (ConGen).

CFIs can fulfill temporary duty (TDY) opportunities. For example, I helped open two offices in Montreal: the Regional Security Office in 2003 and the ARSO-I Office in 2012. I would love the opportunity to help open new DSS offices at other posts.

Pay More Attention to Career Development

Gandjar Gunadi

Chauffeur and Administrative Clerk, U.S. Embassy Jakarta, Indonesia

As a chauffeur and administrative clerk, my duty is to assist the program coordinator and the Export Control and Related Border Security (EXBS) adviser with transportation and logistics. I develop flight itineraries for training participants, book hotels for visitors from other countries and work with Indonesian agencies’ representatives to set up the training venues. I have documented every event we’ve held photographically using the office camera. I also work with the authorized travel agency to get the best flight cost and schedules for EXBS personnel and training participants.

Indonesia has a unique traditional culture. High-ranking people and VIPs in local government are accustomed to being treated like kings. In my daily activities, I assist the program coordinator and EXBS adviser with meetings, seminars and trainings. That puts me in a position to deal with and help VIPs and institution chiefs face-to-face. Sometimes I have to assist them with interpreting, translating, giving directions if they are overseas, filling out forms and ordering in restaurants. I have to do it very politely and carefully, because if I don’t, they won’t be happy, and we don’t want them to be unhappy.

Back in 2012 I had to interpret for a meeting between the EXBS adviser and a one-star general of the Indonesian national police. The general had an interpreter, a policewoman, but the adviser didn’t understand her English. So the adviser asked the general’s permission to use me as an interpreter. It was the first time I had sat down between U.S. and Indonesian representatives. The meeting room was fully air-conditioned, and it was very cold; but still, I got sweaty, because I didn’t want to make any mistakes, and my heart beat very fast. As it happened, the meeting went well; both the general and my adviser were satisfied, and so was I.

There are two simple questions that Locally Employed staff love to hear when a new officer arrives at post. The first is: “What do you think has worked, and what hasn’t?” —Peter McKittrick

On another occasion I escorted a delegation from the Indonesian government to the United States for training and visiting. In a restaurant during the lunch break, one official was confused by the menu, so I offered to help. In the end, I translated the entire menu, including the ingredients in every single dish. He was happy and able to find his favorites. When we got back to Indonesia, this gentleman allowed me to call his cell phone at any time to discuss anything related to his agency.

Generally, the U.S. embassy has a good work environment and atmosphere. The facilities have a good impact on local employees mentally and physically, as well. One suggestion is: Support from the State Department HQ for better career paths in the organization would help FSNs be even more successful in their work.

I see the American employee as a supervisor or beyond. What I would like to see is more attention on career development and more discussion about future plans for the local staff. If an employee deserves an increased grade, then it should be processed smoothly. If the local staff member does the job very well, then he or she deserves to be considered for a reward. It would stimulate them to do their jobs better.

Treat LE Staff as the Professionals They Are

Mabel Stampf

Shipping Assistant, U.S. Embassy Asuncion, Paraguay

Mabel Stampf, at right, receives the 2014 State Department FSN of the Year Award from then-Deputy Secretary of State for Management and Resouces Heather Higginbottom.

Listen to the local employees. They have the knowledge and experience required for the job they’re doing. They understand the culture and know how to handle the different situations.

Treat the local employees with respect and as professionals. They can be of great help to U.S. officers in reaching the section’s goals and objectives. Encourage good and open communication, and share information. Listen to different opinions about a specific subject. Keep a good working environment. This will cause the employees to work happier, harder and more efficiently. Recognize their hard work. Motivation is very important.

Recognize that, as human beings, employees make mistakes. It is important to talk about it and guide them on how to proceed in the future. A supervisor’s words of encouragement are always welcome and can cause a big change in an employee’s morale.

Make LE staff feel that they are part of the team. They will always do their best when they feel they are part of the team.

The embassy should focus on recognizing the local employees’ hard work and experience. Support them by sending employees to training, and after four or five years send them again to update their knowledge and skills.

During the years that the U.S. embassy was under the value-added tax (VAT) reimbursement program, our office had to deal not only with different offices at the ministry of finance but with different ways of interpreting the law to get the reimbursement. As you can imagine, it was not an easy task to go through the different offices talking to Paraguayan government employees about the reimbursement. The process to get the money back from the government of Paraguay was long and complex.

I started looking for a way to solve this problem to the benefit of both the U.S. embassy and the ministry of finance. I worked very closely with the Paraguayan embassy in Washington, D.C., and the Paraguayan government to find a way for the official Americans to avoid paying the VAT, and thus avoid the need for reimbursement. I worked hard with the ministry’s legal advisor on possible solutions. I had the idea of not paying the VAT at the point of purchase to avoid the reimbursement process.

At the beginning, they considered my idea hard to put in place. After one year of working on it, we created a VAT exemption card and drafted the law and regulations to implement it. The minister of finance was very happy and presented it to the ministry of foreign affairs. The solution was accepted and put into effect. This card not only benefits the U.S. embassy and other embassies but also the government of Paraguay, because it doesn’t need to reserve funds to cover the reimbursement.

The most interesting thing about my job is the opportunity to know and work with many different people, both inside and outside the embassy. The opportunity to grow professionally, to listen to U.S. employees’ experience in other countries and to share my experiences with colleagues from other U.S. embassies so we can learn from each other is rewarding. And I appreciate the respect with which my colleagues from other embassies and government offices treat me.

The hardest thing about my job is the change of U.S. supervisors every three years. It is not easy for local employees to deal with changes, just as it isn’t for American employees. It takes time to adjust to each other; get to know each other; understand how to work together; and learn what the U.S. supervisor expects from the local employees, what things we should not say or do, the changes in the procedures and any changes in the preparation of the letters, diplomatic notes and memos.

There is also the continuous change of our contacts at the Paraguayan government ministries; we have to be continuously building good business relationships with the new ones to facilitate our clearance process.

Facilitating Cooperation with Host-Country Officials

Yarden Berkovitz

Criminal Fraud Investigator, Regional Security Office, U.S. Embassy Branch Office, Tel Aviv, Israel

Yarden Berkovitz.

Disrupting organized crime is one of our primary goals at the U.S. Embassy Branch Office in Tel Aviv. To be able to do this successfully, criminal fraud investigators (CFIs) and assistant regional security officers for investigation (ARSO-I) need close contact with the Israeli National Police. Joint investigations require the sharing of information between law enforcement entities.

For example, we had a case in which a visa vendor fraudulently collected $113,000 in fees from 700 applicants applying for U.S. nonimmigrant visas. The financial damage to the embassy and several Israeli credit card companies was enormous. Thanks to close cooperation for several months between the branch office, the INP, Israeli credit card fraud teams and the Israeli state attorney’s office, the vendor was convicted and required to pay the money back to the branch office.

This case is an example of excellent cooperation between the ARSO-I shop and the INP investigative team that brought the case for prosecution. We received recognition for our work from U.S. Ambassador David Friedman.

Recognize Hard Work

Yvette Ter Wolbeek

International Military Training Coordinator, U.S. Embassy Pretoria, South Africa

As a military training coordinator for South Africa, Swaziland (now Eswatini) and Lesotho, my work definitely makes a difference in the daily lives of members of the military in the three countries. The excellent courses the United States offers help them to develop themselves and to contribute to their respective militaries after they return.

For example, one major who went to the U.S. Air Force Squadron Officer School was first in her class. On return, she was promoted to an Officer 05, and became the first woman in the South African Air Force to become commander of an operational aviation squadron. We also made it possible for the first African woman to attend the Air War College; she came back with a master’s degree with A levels. These are only two examples, but in general I have received positive feedback from students.

To help LE staff be even more successful in their work, they should be offered more professional development opportunities— in my field it is limited. Also, it is important to be recognized for your hard work. Sometimes award ceremonies come and go without American officers thinking of their Locally Employed staff.

The most interesting thing about my job is to travel, meeting colleagues in other countries. Our Security Cooperation Education Training Working Group gives us this opportunity annually. It is the highlight of our year.

We Try to Make a Difference, Just Like You Do

Nompumelelo Khanyile

U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Pretoria, South Africa

Nompumelelo Khanyile.

Take your time learning the dynamics in each country; enforcing drastic changes within a few months of your arrival will not always work.

It is understood that in American culture, the louder you are, the more “intelligent” you seem or sound. This may not be the case at the country office. Do not assume that quiet people are slow, stupid or do not know anything. Local staff will withdraw even further if they feel overlooked or talked over. And no, they cannot be trained or taught to be “loud” either. Cultural context is very important.

Attempt to remember people’s names. Chances are, local staff will never forget yours. Also, read how an email is signed and try to respond accurately—the highest form of disrespect is spelling a name wrong when responding to an email from that very person!

Please do not say: “Oh you change your hair so often, I didn’t recognize you” to people of color. This is not a compliment. (Better to remember my actual face, which does not change.) Racism can be very subtle, but believe me, the local staff can always feel it. It can be offensive if you come to a country like South Africa, for example, and we hear that you are taking Spanish or Italian classes (in Africa!). While this is solely within your rights, do try to learn at least one African language when in Africa. Learn a local language, wherever you go!

Lastly, please show confidence in and appreciation for the work being done by the local staff. Yes, we understand it is your taxes at work, and that is why we wake up each day to try and make a difference, just like you do.

Helping to Make Cambodia Safer

Songmeng Chea

Criminal Fraud Investigator, Regional Security Office, U.S. Embassy Phnom Penh, Cambodia

I have served as an interlocutor between the embassy’s regional security office and Cambodia’s top two law enforcement entities— the Cambodian National Police and the General Department of Immigration— which has led to unprecedented local arrests and prosecution of fraudulent visa applicants and scammers, as well as the deportation of numerous Americans wanted for crimes in the United States. During 12 years with the embassy, I have earned the trust of the leadership of the host-country policing agencies, which helps to a large extent to remove red tape.

In my capacity as a CFI, I feel that I have had a big part in making Cambodia a safer place for Cambodian kids through assisting in the removal of U.S. sex offenders from the country.

Provide Space for Honest, Constructive Discourse

Peter McKittrick

Public Affairs, U.S. Consulate General Belfast, Northern Ireland

Peter McKittrick.

Prior to an abrupt and unexpected career change, I worked for the Northern Ireland Tourist Board in Belfast. On a Monday I was on a bus full of American travel writers extolling the virtues of my wonderful little country. By the following Friday I had taken up a position with the State Department, where I was on a different bus taking congressional representatives around our sectarian interfaces, telling them how difficult things were! I suspect the truth is somewhere in between.

The most interesting thing about my job has been and remains the opportunity to view my own country from the outside in.

I believe Locally Employed staff have a huge obligation to be flexible and responsive to the changing needs and personalities of our diplomatic colleagues. Ultimately, it’s not about us.

That said, there are two simple questions that Locally Employed staff love to hear when a new officer arrives at post. The first is: “What do you think has worked, and what hasn’t?” We benefit more than most organizations in our potential to blend fresh perspectives with longstanding institutional knowledge. Sometimes, the instinctive (and perfectly understandable) desire of newly arrived FSOs to make a strong, immediate impact can lead to good things being sacrificed and the not-sogood being implemented.

I would add that appraisal systems can sometimes reinforce that tendency. Something “sustained” doesn’t tend to read as well on a performance review as something “implemented.” Creating the space for honest, constructive discourse can help us preserve the ideas and initiatives that work well, and it can also prompt necessary change on the things that don’t.

We also love to hear, “How can I help you do your job better?” For my part, I’ve been fortunate to have grown professionally in this job, not least because senior colleagues have been prepared to empower me and help me fulfill my potential. The overwhelming majority of local staff I know and work with are extremely loyal, motivated and capable. It’s an incredibly powerful thing when we know that our senior colleagues have our back; and this, in turn, allows us to support them even more.

It would be naïve not to acknowledge the natural tension that can sometimes exist between American officers and LE staff. It can happen when we as locals lose sight of our primary obligation to provide unwavering support for our diplomatic colleagues. It can also happen when LE staff feel unheard, underutilized or underappreciated. But for the most part, I’ve seen amazing things happen when the dynamic works as it should.

Here’s one example. A few months after 9/11, I was tasked to look after a New York firefighter who was visiting Belfast as part of a series of official visits to thank counterparts across the world who had run fundraising events for his organization. He expressed an interest in having a quiet lunch and Guinness in one of Belfast’s traditional pubs. What followed was something that I will never forget. Within seconds of the uniformed firefighter entering into a busy urban bar, every single individual spontaneously took to their feet in a gesture of heartfelt applause. Mindful of his subsequent commitment on a live, televised chat show, my main job at that point was to politely decline dozens of offers to buy him a drink.

If you can, please maintain a sense of humor, because Indonesians love jokes. —Dihya Ihsan

The story may sound melodramatic, but I found myself proud on two levels—first, that a true American hero was rightly acknowledged after the horrors of 9/11, but also that my fellow citizens demonstrated their empathy and support in such a spontaneous and sincere way. It proved that I was now looking at things through an American prism as well as a Northern Irish one.

The consulate’s recent diplomatic energies have focused on America’s willingness to help move Northern Ireland away from a period of serious political unrest. Yet the United States’ reputation as a helpful catalyst and honest broker was not something that developed automatically. Many of my American colleagues were involved in delicate, painstaking diplomacy—much of which went unnoticed. They encouraged, cajoled, listened and, at times, criticized, in an effort to bring about much-needed progress here.

Our consulate was a neutral, safe space where civil society and politicians could interact and address difficult subjects away from the public gaze. Today, the U.S.-Northern Ireland relationship reflects a more normal, mutually beneficial exchange of ideas, trade and tourism. Many here reflect on the U.S. government’s pivotal role in getting Northern Ireland to the much-improved place (politically, economically and socially) it is in today.

“We wouldn’t be where we are today had it not been for the Americans” is a comment we still frequently hear. To me, these sentiments are the out-workings of effective foreign policy, professional diplomacy and a small consulate that has punched well above its weight for many years.

Culture: Share, but Don’t Impose

Stanley Perrier

Human Resources Specialist, U.S. Embassy Port-au-Prince, Haiti

I would advise [American employees] to be more knowledgeable about the culture of the host country. It’s always good to share culture, but not to impose it.

When I started working for the U.S. embassy, I felt a discordance or a certain frustration among the Locally Employed staff. I arranged a one-on-one meeting with the local supervisors to motivate them toward their responsibility as leaders of the group they supervise. This was successful because we wound up organizing an election for an FSN committee that had been obsolete for more than two years before my arrival.

To me, this embassy is one of the best places to work in any country. The Americans are respectful. In my opinion, giving opportunities for employees to go on temporary assignment would help LE staff be even more successful in their roles.

FSNs Have a Critical Liaison Function

Claudia Cordero

Criminal Fraud Investigator, Regional Security Office, U.S. Embassy Mexico City, Mexico

Claudia Cordero.

Criminal fraud investigators here deal with both U.S. and Mexican fugitives fleeing from justice on a daily basis. We prevent Mexican citizens wanted in Mexico from crossing the border or obtaining a valid visa to travel to the United States. Sometimes we help the U.S. law enforcement community by working with law enforcement contacts in the host nation to return U.S. fugitives to the United States.

ARSO investigators in Mexico City contribute to keeping the U.S.-Mexico border secure by working with Diplomatic Security Service field offices in the United States and other law enforcement agencies in the United States. Also, ARSO-Is in other countries provide reciprocal assistance with cases such as passport and visa imposters, Amber Alerts for missing children, trafficking-in-persons cases and human smuggling cases.

We are here to be the liaison between the host-nation authorities and our American supervisors, so Locally Employed staff should routinely be building contacts. In most cases, it is the U.S. embassy that requests support and information from our host-nation contacts. Sometimes LE staff need American officers to attend a meeting with host-nation contacts to convey gratitude or offer assistance, especially in sensitive cases that involve security.

It can be hard to get Mexican authorities to support our cases because they face multiple competing priorities. It is often difficult to explain why our cases should be prioritized, but it is part of my job to explain the bigger picture and place our case or investigation within the context of their own work. For instance, our investigation may not only deal with fraudulent documents, but also with documents related to vendors, organized crime, human smuggling, money laundering rings and possible trafficking-in-persons cases located in Mexico.

The most interesting thing about my job is that the investigations are always different. Documents can easily be purchased or altered in Mexico, and the training we provide to our Mexican contacts on fraudulent travel documents and imposters is an asset to our office. Often, contacts who take these training courses go on to generate successful cases that detect fraudulent documents. This training work helps us learn about other trends and improve our work.

A Win-Win Equation

Khalil Derbel

Political Specialist, U.S. Embassy Tunis, Tunisia

Khalil Derbel.

My journey and career with U.S. Embassy Tunis have been mostly successful and rewarding. Analyzing and explaining the grains of that success and feeling of accomplishment may seem an arduous task, but limiting the analysis to two areas makes it easier.

Part of working in a multicultural setting is bridging two cultures. FSNs not only fulfill their functional duties; more importantly, they are also negotiators, facilitators and no small part of the bilateral relationship. Their native knowledge and understanding of the reality on the ground, and the relationships they build and nurture with a broad range of contacts, are essential elements of informed analysis and pertinent reporting. All local staff can contribute, not just political and economic assistants. Yet American staff often overlook the valuable insights to be gained from a driver or shipping assistant.

A large audience of policymakers in Washington rely on information from post to make proper decisions. I have been in that position many times. Once when a prolonged security and political crisis hit Tunisia in 2013, I kept close watch for breaking events and arranged meetings for the political and economic counselor with various parties on almost a daily basis, so that we got a sense of what was at stake for each actor. This helped us convey wellinformed messages to policymakers and facilitated timely support from the U.S. government to democratic forces. Following the election of a new parliament and the formation of a new government in early 2015, my work as the lead embassy contact with parliamentarians contributed to easier embassy access to the number one institution in the country and helped the work of the economic section, the Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs and USAID.

Like American employees, LE staff have career goals and aspirations. Therefore, career mobility at post is a reality and often a necessity. I have experienced it, and so have many colleagues. I spent 15 years teaching at the Foreign Service Institute Tunis Arabic Field School, so the decision to close the school was a life-changer for me. I made the right decision in the end to stay with the same employer and moved on to a new job as grants analyst at the U.S.-Middle East Partnership Initiative’s Tunis Regional Office. That assignment, which lasted for one year, turned out to be one of the most rewarding. It barely took a few weeks for me to find a way to positively contribute to the work of the section. I also learned that experience accumulated and skills acquired over the years always come in handy. All the skills we take for granted, such as organizational, drafting and interpersonal skills, are good and useful for most jobs.

When a higher position opened in the political/economic section, I jumped at the opportunity. This was yet another big career change, but an enjoyable chapter, too. I still recall my first days as a novice political specialist trying to find a place in one of the busiest hubs of Embassy Tunis in a country that was going through a major political transition. To my benefit, the margins of progress ahead of me were wide and the motivation to apply myself to the task was high. I also owe part of the success of my own transition to the tremendous support I received from the section and the mission’s leadership. I am grateful to Embassy Tunis for adopting preferential hiring for FSI teachers, and for sustaining a policy that encouraged personnel to move up whenever their background and skills matched a vacant position. I believe this is a win-win equation.

I have also come to enjoy the role of informal mentor for LE staff colleagues. I often discuss with them the highlights of my career and real experiences I have been through, and share some of the ingredients of success. Having made rewarding career moves prompts me to encourage younger colleagues to invest in their careers, and to think big for themselves and their future.

The Value of Politeness

Dihya Ihsan

Program Coordinator for Export Control and Related Border Security (EXBS) Program, U.S. Embassy Jakarta, Indonesia

Dihya Ihsan.

Indonesians value politeness in every aspect of life, including in the work environment and ways of doing business. Indonesians are reluctant to say “no.” They prefer to use other ways to express a negative response in a more polite manner. Further, Indonesians are not straightforward in expressing opinions. Many Americans find this frustrating and irritating.

American colleagues often have difficulty understanding the outcome of any discussion with local staff or Indonesian government representatives, and will try to consolidate many vague opinions and interpret the precise meaning themselves. Consequently, achieving consensus will usually take a while.

There are cases where local staff and American employees end up with tension and conflict because of misunderstanding each other’s perspective. The best way to cope with this situation is to maintain flexibility in your expectations. Do not lose your temper if the response does not meet your expectations. It just needs a little time to achieve consensus and get things clearer. Anger will worsen the situation and lead to team dysfunction. Be assertive without losing the element of politeness. Courtesy is essential. If things go wrong, try to form a statement rather than a question that will corner a person. If you can, please maintain a sense of humor, because Indonesians love jokes.

This might lead to lots of adjustment in the pace of your work. Milestones you set may slide, and your timeline may be unmanageable. But this will keep the working environment healthy.

In bilateral cooperation, buy-in from the host government is essential. I spearheaded a coordinated approach to engage our Indonesian government counterparts to support the EXBS program. I meet regularly with host-country officials of relevant ministries, Grand National Assembly parliamentarians and ASEAN or European Union delegates or representatives to identify deficiencies, avoid duplications and discuss ongoing projects. Our program receives significant support from the government. This contributes to strengthening the relationship between Indonesia and the United States, particularly in the field of export control and border security.

The most interesting thing about my job is I have the privilege of traveling around the world. I have the opportunity to experience different cultures, foods and attractions in the course of working, namely organizing capacity-building training events, exchange visits and study tours for our government delegations, most of which take place overseas. I am responsible for escorting the delegation when attending the training. This is a perk of my job which other FSNs do not get.

American officers could help FSNs to be more successful by involving them in making strategic decisions and by realizing that FSNs are also capable of managing big projects. Give them the opportunity to shine by allowing them to make authorizations. This will optimize their potential and make LE staff more successful in their work.

LE Staff Participation Essential

Patrick L. A. Wiss

Procurement Agent, Member of the Tri-Mission Rome LE Staff Board, U.S. Embassy Rome, Italy

On arriving at post, direct-hire Americans should learn to accept and appreciate cultural differences to establish a profitable working relationship.

I have worked to increase opportunities for Americans and local employees to get to know each other. I translated flyers about leisure activities available on and off the embassy compound into Italian to encourage LE staff to participate and not feel excluded a priori.

In 2006 I organized an after-the-summer-holidays “Welcome Back Bash” with the Community Liaison Office, a musical event with a live band. All U.S. embassy direct hire and Locally Employed staff were invited to come along with their families and local friends to spend a relaxed time together. It turned out to be so successful that it was repeated for several years, bringing people of different cultural backgrounds together in perfect harmony.

The embassy should focus on replacing LE staff in time when one retires to maintain the high-level standards required. LE staff are primarily inclined to work for the U.S. government because of their admiration for the United States. This should be considered the basis for establishing a productive working relationship based on mutual respect and obtaining best results.

Empowerment Works

Noviani Basar

Criminal Fraud Investigator, Regional Security Office, U.S. Embassy Jakarta, Indonesia

Noviani Basar.

In my four years with the embassy, I have developed relationships with Indonesian immigration, police, airline and civil registry personnel by teaching them how to detect fraudulent passports and visas. I have also facilitated opportunities for them to receive training in the United States, so they could enhance their skills and further strengthen the U.S.- Indonesia strategic partnership in law enforcement.

My job is not just about investigating fraud cases or making connections with our counterparts. Using interpersonal skills, I am able to liaise with and maintain relationships with the Indonesian government. For example, when a U.S. military plane had to make an emergency landing in Banda Aceh, I was asked by my supervisor to assist our defense attaché’s office to seek permission from immigration for the air crew to deplane at the airport and enter the city. It was a difficult negotiation because most of the crew did not have passports with them. My immigration contact told me that he was hesitant to speak to our deputy chief of mission about the situation.

Banda Aceh is a sensitive area in Indonesia where the unexpected landing of a U.S. military plane could be considered a potential threat to the country. The Indonesian government was afraid that the emergency landing was an intended action by the U.S. government to infiltrate the area. Although there was a day-long delay for the crew to be permitted to enter the city, immigration officials finally issued an emergency short visit pass to the crew, who departed the next day without incident.

The best thing about my job is having the ability to communicate directly with our counterparts to advance our relations. Under the direction of my supervisor, I am empowered to do this, and it has given me the opportunity to nurture ties, develop trust and build a mutually beneficial relationship that strengthens the U.S.-Indonesian partnership.

Working at the U.S. embassy has been a great opportunity for my personal and professional growth. It is a fun place to work and a great place to learn more about American culture, as well as U.S. government policies and programs and their positive impact on Indonesia.

The mission participates in many programs that contribute to the community. One suggestion I have is to include the children of Locally Employed staff in the summer-hire program. There is a summer-hire program for U.S. college and high school students, but not one for the children of LE staff. I feel such a program would be of great benefit to the embassy community.

Building Bridges to Prosperity

Angela Turrin

International Trade Specialist, U.S. Embassy Madrid, Spain

Angela Turrin.

One sunny day in 1995, I was walking up a street in São Paulo, Brazil, to go visit my grandmother when I noticed a beautiful building on the corner of her new street. The sign read “U.S. Commercial Service,” and the U.S. flag was flying outside. Entering the building was easy back then, and I walked in and read all the information on a board displaying the several sectors and activities that amazing office covered.

As I was reading, a lady named Marina Konno approached me. She asked if she could help me. “I speak English, and am looking for a job,” I answered. “What do you do here? Where can I leave my CV?” (You are probably wondering how I had a CV on me—yes, I was carrying a copy. Coincidence? Luck? Destiny!)

I gave my information to Marina and left the building, not knowing that this simple action would change my life forever. The next day I received a call from her, got an interview and the following day was offered a job to help coordinate a trade mission. That is how my love story with the U.S. Commercial Service began.

In 2001 I applied for a position in Madrid and transferred to fulfill a dream and live an adventure as I explored new work possibilities. It was a perfect fit with my personality. Twenty-three years have gone by since that first day, and I have worked in every single position this organization can offer, from back office to front office, and in different sectors and regional projects. My friends ask where I find the motivation. It’s easy; in the passion to carry on the mission of building bridges to prosperity.

I am fluent in four languages and have lived in four different countries. Knowing how to address cultural change and adapt to it is an asset I learned in the crib, and it helps me every day— both in the trade work we do and in connecting with the many Americans who carry out the U.S. mission at embassies around the world and the many clients who are looking for opportunities overseas.

Like American employees, LE staff have career goals and aspirations. —Khalil Derbel

What has always impressed me about the work we do in the Commercial Service is that it never gets boring. We always have new projects and new challenges that make our work exciting. We are always exploring new possibilities for connecting U.S. organizations to help them broaden their reach. I am sure that without our offices the U.S. economy would be greatly affected, because we help to support and generate an activity that can only be achieved through exporting. I feel I am making a difference every day.

Our engagement with the American officers is based mainly on trust and knowledge. They can feel confident about consulting with the local staff and really hearing the advice and suggestions we provide to help them feel welcome and quickly engage with the local issues and business contacts. We are the force that gives continuity to the mission.

Over the years I had many great American officers who served as mentors. Bravery is a distinct trait they all have in common, combined with the trust and empowerment that are needed for innovation to flourish. These are the best qualities in great leaders that I so admire.

Despite the very important role Locally Employed staff play, we often feel overlooked and forgotten during the many administration changes and priorities. The local team can always use more support and incentives from the incoming officers. Starting off on the right foot will facilitate a smooth transition. Addressing office politics and human resource issues can be a delicate matter, but very necessary to keep our organization healthy and growing.

We need real diversity of thought and experience, and an inclusive mindset to build good export programs. The power of inclusion can only happen when individuals bring their authentic self to work and know that they are heard, recognized and respected.

When Doing Your Job Lands You in Jail

Locally Employed staff members sometimes suffer for their careers in ways we can’t quite fathom. Such is the case with Turkish citizen Hamza Uluçay, a 37-year employee of the U.S. consulate’s political section in Adana, Turkey, who has spent almost two years in jail because of his work for the U.S. government.

In February 2017, Turkish authorities detained and questioned Uluçay because of his routine contacts with local Kurdish groups on behalf of the consulate. Uluçay was ultimately arrested and charged with being a member of a terrorist organization. Turkish press reports claim that the evidence against him includes 21 one-dollar bills that were found in his home, along with books about Kurdish politics and terrorism.

Seven months later, in September 2017, Turkish authorities struck again, this time in Istanbul, where they arrested Metin Topuz, a 20-year veteran of the consulate whose job was to support the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration’s work in Turkey. Topuz was also charged with membership in a terrorist organization, along with espionage and attempting to overthrow the government.

A third employee, Mete Canturk, who also works at the consulate in Istanbul, was placed under house arrest in January 2018 for alleged ties to the Gulen movement—an organization run by Turkish cleric Fethullah Gulen, who lives in Pennsylvania as a permanent U.S. resident, and whom Turkish authorities want to have extradited to Turkey to face charges that he orchestrated a failed coup in Ankara in July 2016. Canturk's wife and child were also detained, but were later released.

The State Department has been advocating for the release of the three men. In November 2017, then-Deputy Assistant Secretary for European and Eurasian Affairs Jonathan Cohen told the U.S. Helsinki Commission: “It appears to us that Mr. Uluçay and Mr. Topuz were arrested for maintaining legitimate contacts with Turkish government and local officials and others in the context of their official duties on behalf of the U.S. government.”

The State Department suspended nonimmigrant visa services on Oct. 8, 2017. Full services were resumed on Dec. 28, after the Turkish government assured the embassy that no additional employees were under investigation and Turkey would give the United States advance warning of any future arrests.

All three men remain in legal jeopardy, either in prison or under house arrest, as U.S. officials fight to get them freed and the U.S.-Turkish relationship continues to suffer.

Pointing to the significant political capital expended by President Donald Trump to get Turkey to release American pastor Andrew Brunson, former U.S. Ambassador to Turkey Eric Edelman and Professor Henri Barkey, a fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations, co-authored a July 29 Washington Post article reminding the world that the three Locally Employed staff were still being held “on bogus charges.”

On Aug. 3, Secretary Mike Pompeo met privately with Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu to push for the release of Brunson and the three local employees.

Pastor Brunson was released on Oct. 12; Uluçay’s request to be released was denied that same day. As of mid-October, Uluçay and Topuz remained in prison, and Canturk was under house arrest, unable to return to work.

Visiting Turkey on Oct. 12, Sec. Pompeo raised the profile of these cases by visiting with their families. In a tweet marking Brunson’s release, the Secretary wrote: “We hope that the Turkish government will quickly release our other detained U.S. citizens and State Department Locally Employed staff.”

—Donna Scaramastra Gorman, Associate Editor

FSN Emergency Relief Fund: How You Can Help

In 1983, after the bombing of the U.S. embassy in Lebanon, a group of Locally Employed staff at our embassy in Santiago, Chile, wanted to help LE staff in Beirut who were injured in the attack, so they passed a hat and collected funds for the families of their Lebanese counterparts. The funds they raised were augmented by AFSA, DACOR and others. In all, $84,000 was distributed among family members of LE staff in Beirut, and the Foreign Service National Emergency Relief Fund was born.

Since that time, the fund has provided financial assistance to Locally Employed staff who have been affected by a crisis at post, such as a natural disaster, civil unrest, targeted attacks or an injury in the line of duty.

The fund is composed entirely of donations from Foreign Service members, groups such as AFSA, AAFSW and DACOR, and LE staff members themselves. Over the past 10 years, according to Chanel Wallace of the Office of Emergencies in the Diplomatic & Consular Service (M/EDCS), more than $3 million in donations have been distributed to LE staff and their families worldwide.

Donations are tax-deductible and can be made by Civil Service employees, Foreign Service members, LE staff and private-sector individuals. Because there are no administrative costs, 100 percent of donations go to LE staff in need.

How to donate:

Secure online donations can be made directly from your bank account or by credit/debit card to pay.gov.

Checks made payable to the U.S. Department of State, designated for the FSN Emergency Relief Fund, may be sent to: U.S. Department of State, Attn: K Fund and Gift Fund Coordinator, 2201 C Street NW, Room 3214, Washington DC 20520.

State, LE staff and overseas American employees of other federal agencies on the Department of State payroll can make contributions by payroll deduction. Cash contributions in U.S. dollars or local currency can be made through the embassy or consulate cashier.

For more information on the FSN Emergency Relief Fund, go to 3 FAM 7160 (https://fam.state.gov/FAM/03FAM/03FAM7160.html) or email MEDCS@state.gov.

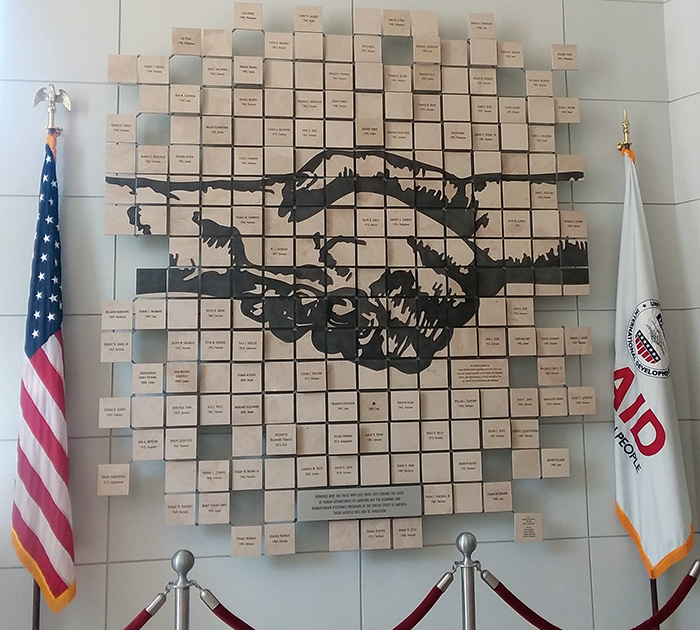

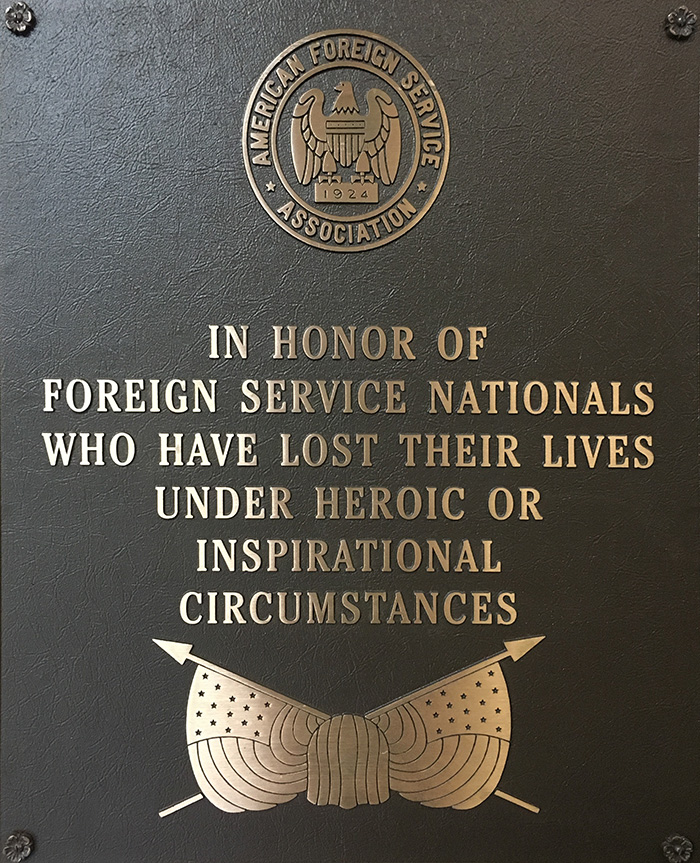

FSNs’ Service, Sacrifice Honored

In serving the United States, Locally Employed staff/Foreign Service Nationals take particular risks to do their jobs. As we highlight the tremendous work and experience of local staff worldwide, we must pause to remember and pay tribute to those who have lost their lives in the line of duty.

All around Washington, D.C., you’ll find monuments to our fallen heroes and historic figures, not just on the Mall but scattered among the traffic circles and parks that make up the District. And so it is only fitting that the U.S. government honor the sacrifices made by Locally Employed staff.

Visit the C Street Lobby of the U.S. State Department and you will find a plaque in honor of “the Foreign Service Nationals who have lost their lives under heroic or inspirational circumstances.” At USAID’s headquarters building, you can pay your respects at the Memorial Wall in the lobby, which is etched with the names of all USAID employees who have died in the line of duty.

Some of these deaths made national or even international news when they occurred. Others happened quietly, with little public notice or attention beyond the walls of the embassy in the country in which they occurred.

But each of the victims whose death is recorded through these memorials made the ultimate sacrifice on behalf of our country and their own as they worked to promote international peace and prosperity.

We remember their sacrifices, and we thank them for their service.

–The Editors