From the FSJ Archive: 9/11, War on Terror, Iraq and Afghanistan

Outpourings of Sympathy and Support

The outpourings of sympathy, condolence and support were immediate and widespread. The president issued a strong letter and declared a day of mourning during which all flags in the country were flown at half-mast. Countless government officials and Ghanaians from all walks of life phoned, faxed and mailed in messages of sympathy. The American Chamber of Commerce organized a memorial service at which two local youth groups—a choir and an orchestra—performed.

Although there have been no demonstrations, editorial comment has been universally sympathetic, while urging the United States to temper any tendency to react emotionally, to act multilaterally rather than unilaterally and to avoid actions that could inflame Christian-Muslim tension. Much concern has been expressed about the impact on developing nations’ access to credit and development assistance.

—Brooks A. Robinson, FSO, Embassy Accra, in Part I of a compilation, “FSOs and FSNs Recall 9/11,” in the November 2001 FSJ.

Iraq PRTs: Pins on a Map

Bob Pope sums up the Iraq PRT program this way: “The PRT concept is both too early and too late—too early because you can’t do development and institutionbuilding in live-fire zones and too late because, four years into this war, it’s way past the time when we have any hope of winning the hearts and minds of the Iraqis. They have been disappointed too many times to believe much of what we say. After hundreds of millions, if not billions, spent on a laundry list of projects, most Iraqis still don’t have potable water, reliable electrical service, operational sewer systems, jobs, a functioning economy or, most important, personal security. Building a few more wells and creating a few more short-term cleanup projects will not impress these people.” …

Unarmed diplomats flanked by armed personnel on military teams in active combat zones, outside of an embassy structure, in the Iraqi provinces—these may be the faces of the “expeditionary Foreign Service” that is called for by Secretary Rice. But while the Foreign Service is expected to “step up” and serve in Iraq, they should, in turn, be able to expect to be sent only to places where they can actually do their jobs and meet with key interlocutors, where there is a chance that they can play an effective, meaningful role. They should be able to expect that they will not be used simply as “pins on a map” for PowerPoint presentations back in Washington.

—Shawn Dorman, FSJ editor and former FSO, from her article of the same title in the March 2007 FSJ.

Salvaging the Afghanistan Venture

Afghanistan remains a victim of international intervention that has empowered some of the worst elements of society and trapped its people in a foreign-made political system that ignores their history, tradition and political realities.

While some of this intervention has been well meaning, much of it has been self-serving, reflecting the national ambitions and interests of other countries. Afghanistan was the first victim of Taliban misrule and al-Qaida brutality. It deserves another chance in a new political system mandated by a traditionally organized loya jirga that reflects the nation’s history and reality and is perceived by Afghans as legitimate.

—Edmund McWilliams, FSO (ret.), from his article of the same title in the July-August 2008 FSJ.

Life Choices Shaped by That Day

On Sept. 11, 2001, I was a blond-haired, green-eyed, slightly naïve college student from a small town in southern California who knew very little about Afghanistan and even less about al-Qaida. The events of that day irrevocably altered the shape of my dreams and the course of my life.

I was fortunate enough not to lose any loved ones in the attacks, but the force of the change in my perception of the world blew the doors of my cozy, safe, insular world wide open and brought with it the realization that nothing would ever be the same again. For those of us who became adults post-9/11, our life choices have been indelibly shaped by that day. I eventually joined the Foreign Service and, when bidding on my second tour, readily volunteered for service in Afghanistan. I will spend the tenth anniversary of the 9/11 attacks posted to Kabul as an assistant information officer in the public affairs section.

The story of Afghanistan over the past few decades has been saturated in blood and punctuated by displacement and destruction. I hope that our work here will ensure that the next chapter is one of hope, reconstruction and reconciliation.

—Erin Rattazzi, FSO, Embassy Kabul, from her note in the compilation, “The Foreign Service a Decade After 9/11,” in the September 2011 FSJ.

The Dust of Kandahar

It was the youth of those around us that was so striking. One lieutenant who directed my security on several trips to Kandahar had only recently graduated from West Point. One private seemed so young that I was tempted to ask him: “Do you have a note from your parents giving you permission to participate in this war?”

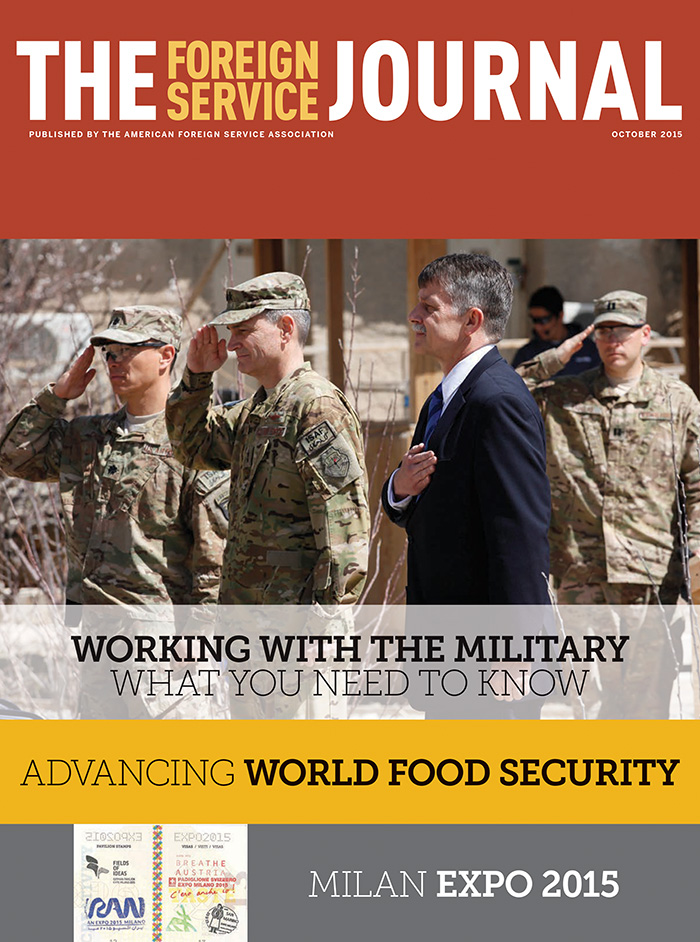

As the senior civilian representative for the U.S. embassy in southern Afghanistan from August 2012 until August 2013, I covered four provinces with a collective population of more than three million people, scattered over an area the size of Kentucky or South Korea that was mostly desert.

Our efforts at outreach followed in the footsteps of those who preceded us. But now, more than a decade after we had helped Afghans overthrow the Taliban, our task had evolved to paving the way for our own pending departure while dispelling any sense of “abandonment.” We told our local contacts that it was now time for them to write their own narrative and achieve their nation’s destiny.

Five of us flew up early that morning to meet our civilian colleagues on the Zabul Provincial Reconstruction Team, discuss education issues with Governor Naseri and visit a local school. … Anne Smedinghoff was only 25, young for an FSO who was already well into her second overseas assignment.

We talked briefly on the tarmac as we waited for our helicopter against the early morning sun, the sky a perfect blue. This was Anne’s first trip to Kandahar. … She mentioned that during a recent vacation, she had cycled across Jordan. I also chatted with my translator, Nasemi, who was supporting a large extended family stretching from New York to New Zealand.

Within hours both Anne and Nasemi were dead. Two other civilian State Department employees—Abbasi … and Kelly Hunt … —were injured, Kelly critically. Three soldiers walking beside us were also killed that day: Staff Sergeant Christopher Ward … Sergeant Delfin Santos … and Corporal Wilbel Robles-Santa. All three were born in 1988. …

Not a day goes by when I don’t relive what happened on that cloudless morning, recalling every moment as it unfolded, reliving endlessly what might have been. …

The next day I attended the ramp ceremony for my colleagues, accompanying their remains on the long journey home. We started with five flag-draped aluminum boxes in Kandahar and added four more in Bagram, bringing the American death toll for that day to nine.

Three days later, I returned to Kandahar for the remaining 20 weeks of my tour. But I have never quite left Afghanistan behind, and probably never will.

—Jonathan Addleton, FSO (ret.), from his article of the same title in the October 2015 FSJ.

The Global Coalition to Defeat ISIS: A Success Story

Sometimes a truth spoken resonates so organically that it prompts a collective sigh of relief from its listeners—relief that someone has emerged from the crowd to suggest a path forward, allowing us all to shift our footing from collective outrage to collective action. That is the essence of the story behind U.S. leadership of the Global Coalition to Defeat ISIS. During the first six months of 2014, the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria … made a dramatic debut on the world stage by capturing a wide swath of Syria and Iraq. It rolled seemingly without resistance through Fallujah, Raqqa, Tikrit and Mosul, even threatening the gates of Baghdad, before announcing the establishment of a caliphate (Islamic state) and declaring Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi as caliph—the successor to the Prophet Mohammed. The speed of the advance, the confidence portrayed through their polished media arm, and the stories that emerged about the horrors of life under ISIS and the persecution of innocents shocked and horrified the world. … On Sept. 10, 2014, President Obama … announced “that America will lead a broad coalition to roll back” ISIS. The campaign would seek to “degrade, and ultimately destroy, ISIL through a comprehensive and sustained counterterrorism strategy.” Concluding his address, President Obama said, “This is American leadership at its best: We stand with people who fight for their own freedom, and we rally other nations on behalf of our common security and common humanity.”

—Pamela Quanrud, FSO (ret.), from her article of the same title in the January-February 2018 FSJ.

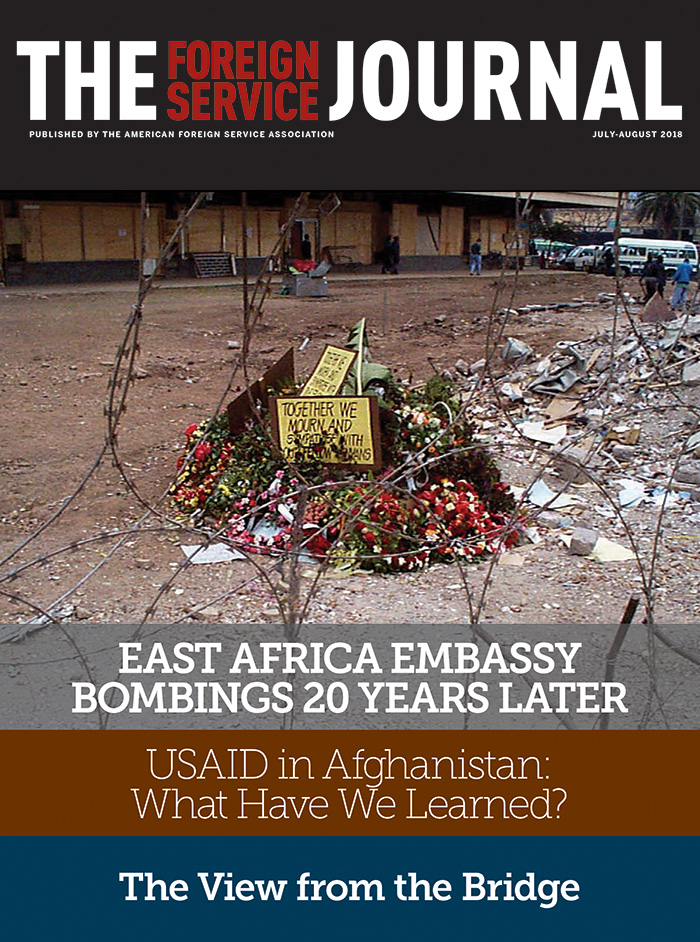

The Practice of Leadership at Every Level

A huge bang with the weight of a freight train bore through the room, throwing me back. The building swayed; I thought I was going to die. I blacked out for a moment, came to and descended the endless flights of stairs with a colleague. Only when we exited the building did I see what had happened to the embassy. I realized in an instant that no one was going to take care of me, and I had better get to work. …

I would like to pass on the following advice for those who may become survivors and helpers in the future.

• Get involved in the community and help to grow teams that learn how to do things together. This will be essential in catastrophes and highly satisfying otherwise.

• Be kind to yourself, and be kind to one another.

• Take care of your people—and take care of yourself, too.

• Allow spouses, family and friends to take care of you.

• Seek professional help to stay resilient.

• To help after a crisis, be clear about your mission and adapt to reality.

• Build a bridge between “we” and “they” to create the trust that will make recovery easier.

• Don’t expect this to end any time soon. Catastrophes breed crises, and some go on for years.

• Find meaning in the event—the “treasures among the ashes.”

• Do not depend on the media or our political leaders to keep the story alive or create change; both have short memories.

• Remember, it will get better.

—Prudence Bushnell, FSO and U.S. ambassador to Kenya, from her essay of the same title in the compilation, “Reflections on the U.S. Embassy Bombings in Kenya and Tanzania 20 Years Later,” in the July-August 2018 FSJ.

For further related reading, go to these archive editions at www.afsa.org/fsj-archive:

- “Are We Losing the War on Terror?” by Philip C. Wilcox Jr., September 2004

- “Operation Iraqi Freedom: The Arab Reaction,” by Khaled Abdulkareem, March 2004

- “Reality Check in Iraq,” by David L. Mack, March 2005

- “Iraq Service and Beyond,” by Shawn Dorman, March 2006

- “The Implications of Iraq and Its Impact on the Region,” by Edward Walker, December 2006

- FOCUS on “An Uneasy Partnership: The Foreign Service and the Military,” March 2007

- “Remembering USAID’s Role in Afghanistan, 1985-1994,” by Thomas H. Eighmy, December 2007

- FOCUS on “Slogan or Substance: The Legacy of Transformational Diplomacy,” January 2009

- “Counterterrorism: Some Lessons to Consider,” by Alan Berlind, June 2009

- “The Diplomat as Counterinsurgent,” by Kurt Amend, September 2009

- “Microdiplomacy in Afghanistan,” by Matthew B. Arnold and Dana D. Deree, January 2011

- FOCUS on “Reflections on 9/11—How the Foreign Service Has Changed,” September 2011