Getting into the Game: America’s Arctic Diplomacy

Climate change is opening up new opportunities and challenges in the Arctic. Is the United States ready to lead?

BY ÁSGEIR SIGFÚSSON

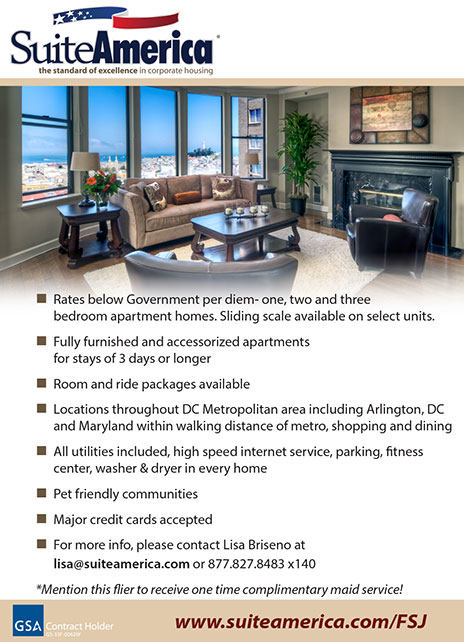

A view of Iqaluit, the city on Baffin Island in the Canadian Arctic that hosted the Arctic Council Ministerial on April 24. In the background is the airport and runway. Iqaluit was built as a World War II airfield to refuel military aircraft en route to Britain.

Miguel Rodrigues

AFSA / Jeff Lau

When new diplomatic opportunities appear, the United States is typically quick to react and establish a presence. After the fall of the Soviet Union, new embassies were staffed up and opened in record time across Eastern Europe and Central Asia. The breakup of Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia saw similar quick responses from the United States, as did the appearance of new nation states such as Timor-Leste and South Sudan. U.S. embassies opened soon and resources were allocated swiftly. So why has Washington been comparatively slow in responding to the explosion of opportunity in the Arctic?

The scientific consensus is that climate change is mostly behind the swift warming of the Arctic, and other Arctic nations, as well as China, have moved decisively to stake their claims in this new arena. As the climate heats up, the race for the Arctic’s resources will do the same; new shipping lanes will become available; environmental changes will accelerate; and large populations will be affected. Under the circumstances, is the United States playing the leadership role that might be expected?

Earlier this year, the United States began a term as chair of the Arctic Council, the inter-governmental forum with primary responsibility for dealing with Arctic issues. Decisions are made by consensus in the council, whose members are the eight Arctic nations: the United States, Canada, Denmark (by way of Greenland), Iceland, Norway, Sweden, Finland and Russia.

Founded in 1996, and with its headquarters in Tromsø, Norway, the council focuses on cooperative issues such as environment and climate, biodiversity, oceans and Arctic peoples. Since its establishment, the body has accepted a number of observer nations: France, Germany, the Netherlands, Poland, Spain, the United Kingdom, China, Italy, Japan, South Korea, Singapore and India.

During the next two years, the focus of the U.S. chairmanship will be on three issues: improving economic and living conditions for Arctic communities; enhancing Arctic Ocean safety, security and stewardship; and addressing the effects of climate change. All are worthy issues, to be sure. But one might ask why the United States is not using its chairmanship to prepare the council for the challenges immediately ahead. Why is there no direct emphasis on security, territorial claims, resources and access—the old standards of geopolitics—in the U.S. agenda? Those are the areas where one might logically expect some diplomatic tensions to arise in the coming years—and where, in some cases, they already have.

During its short existence, the Arctic Council has been an important venue for multilateral negotiations, facilitating agreement among the Arctic nations to cooperate on a variety of issues, including marine oil pollution and regional search and rescue. But should it evolve to the point where members can address “harder” issues, and should it play a greater, more dynamic role in Arctic affairs? These are larger questions, which the United States might consider raising during the next two years.

State of Play

In the last decade, the council’s member states have increasingly turned to the Arctic as a vitally important part of their foreign (and domestic) policy. Non-Arctic nations are looking north, as well; China, in particular, is taking serious steps toward becoming a player to be reckoned with in the Arctic. Here are some details.

Russia. Russian President Vladimir Putin has made no secret of his desire to exert Russian influence in the Arctic. Possibly the most memorable image related to the Arctic in recent memory is of the 2007 planting of a Russian flag on the seabed beneath the North Pole. While dismissed as a stunt by the other Arctic nations, it made Russian intentions clear. In August 2015, Russia submitted a claim to the United Nations for large swathes of Arctic territory. (Other nations have done so as well.) Russia has also returned—very publicly—to many of the Arctic military and navy bases it abandoned after the fall of the Soviet Union. A permanent Russian military presence in the country’s Arctic areas is declared policy, as is significant control over the sea route north of the Russian mainland.

According to a 2009 Kremlin strategy paper, the Arctic is to become Russia’s “top strategic resource base” by 2020.

According to a 2009 Kremlin strategy paper, the Arctic is to become Russia’s “top strategic resource base” by 2020. Russia also has its eye on the possibly immense stores of oil and gas resources in the Arctic; some estimate that up to 25 percent of the world’s undiscovered oil and gas may be located in the region. Russia is not alone in building up its military in the Arctic, and is far from the only actor with designs on its resources. An arms race is certainly not imminent, but it is worthwhile to pay close attention to Moscow’s actions.

Canada. With more than 100,000 Canadians living in the Arctic, Canada has the largest land mass of any country in the region. Canada has just finished its second term as chair of the Arctic Council, culminating in a ministerial meeting in Iqaluit, the capital of Nunavut province. Canada’s policy in the Arctic has been unusually muscular, with a strong emphasis on the military and sovereignty components of its overall strategy.

In fact, Prime Minister Stephen Harper told reporters in 2010 that while Canada has many priorities in the Arctic, including community, environment and governance, “all of these [other priorities] serve our No. 1 and, quite frankly, non-negotiable priority in northern sovereignty, and that is the protection and the promotion of Canada’s sovereignty over what is our North.” Canada has also been the most vocal in opposing aggressive Russian moves into the Arctic, including the flag-planting episode in 2007. Canada’s military exercises in the Arctic have also become more frequent and longer in duration.

The Nordics. The five Nordic countries—Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden—emphasize military strategy in the Arctic less than the other three Arctic nations, simply because none of their militaries are in any way comparable in size or capability. In fact, Iceland does not maintain a military force other than a coast guard. Instead, they have focused on resources (including oil and gas but also fisheries), strong cooperation on environmental, shipping, maritime and search and rescue issues, and cultural and community elements, including indigenous peoples.

A titanium capsule with the Russian flag as seen moments after it was planted on the seabed beneath the North Pole on Aug. 2, 2007, by a Mir-1 minisubmarine during a record dive 2.5 miles beneath the surface of the Arctic Ocean. The voyage conducted studies of the climate, geology and biology of the polar region. AP Photo / Association of Russian Polar Explorers

All five countries have, moreover, woven the Arctic into their own foreign and domestic policies to a significant degree, including strong domestic commitment to scientific research and environmental protection in the region. This is not to say that they speak with one voice on all issues. Diplomatic egos in Sweden, Finland and Iceland have been bruised by Denmark and Norway snubbing them in forming a “group of five” (together with Canada, Russia and the United States) within the Arctic Council on the basis of the five’s special status due to their extensive coastal areas within the region. But having had control of the Arctic Council for 10 years out of every 16, the Nordics are very important actors on Arctic issues.

China. Technically speaking, China is not an Arctic nation. No part of China extends north of the Arctic Circle, and China does not have any territorial possessions in the Arctic. Yet Beijing has acted in ways that make its interest in the Arctic quite clear, both officially and unofficially. While urging the world to keep the Arctic outside the sovereignty of any one state, or group of states, China is simultaneously expanding its influence within the Arctic nations, particularly in Iceland and Norway.

Huang Nubo, a Chinese businessman with strong ties to the country’s government, sought to purchase a large piece of land in Iceland (where his request was rejected) and Norway, where he successfully acquired a sizeable tract close to the northern city of Tromsø. While Huang denies that he is acting on behalf of Beijing, many see the hand of the Communist Party in these dealings. In Iceland, the Chinese embassy has quickly become the largest foreign embassy in Reykjavík and Iceland-China ties are rapidly expanding.

China’s main interests in the Arctic appear to be threefold: curbing Russia’s influence in the region; securing access to the shipping route north of Russia for shorter shipping times to Europe and North America; and developing positive relations with nations that may hold the key to major future energy resources in the Arctic. China is well prepared for the Arctic’s future and appears ready to assume a major role there as conditions change.

A Q&A with Special Representative for the Arctic Admiral Robert Papp

1. Do you feel that enough resources (money, staff, etc.) are provided to adequately address Arctic issues?

In a resource-constrained environment, we have been fortunate that the State Department has directed sufficient resources to fulfill the requirements of a successful Arctic Council chairmanship. The administration has also looked for ways to elevate efforts in the Arctic across the government by standing up the Arctic Executive Steering Committee to coordinate and prioritize activities, making the most of resources in each department and agency. Further, during President Obama’s recent travels to Alaska, he committed resources to specific initiatives related to renewable energy, energy efficiency, coastal erosion, and safety and security in the Arctic.

2. Is the United States concerned about the Arctic plans of other nations, specifically Russia and China?

At the current time, the sovereignty rights of the eight Arctic states are globally recognized and respected, and the United States has no immediate concerns with the Arctic plans of other nations. Although Russia’s aggression in Ukraine has strained its relations with the Arctic states and has complicated some of our work on Arctic issues, we continue to work with Russia through the Arctic Council and are maintaining activities related to protecting the Arctic environment, ensuring maritime safety and conducting law enforcement operations. China’s role as an observer in the Arctic Council enables China to be aware of issues that may affect the country’s interests, and provides a mechanism through which China can contribute to the work of the council.

3. Beyond climate change, what is the No. 1 strategic U.S. goal in the Arctic?

President Obama and Secretary Kerry have both affirmed that a secure and well-managed Arctic marked by international cooperation is a key priority of the United States. The Arctic Executive Steering Committee, charged by executive order to prepare for a changing Arctic and to enhance coordination of national efforts, will implement a comprehensive and long-term vision for our Arctic engagement through the National Strategy for the Arctic Region.

4. Would a Senate-confirmed “Ambassador-at-Large for Arctic Affairs” help elevate the profile of Arctic issues?

The establishment of a special representative position was an important step in demonstrating the State Department’s commitment to the Arctic and ensured visibility of Arctic issues at the highest levels of our government leading into the preparations for the Arctic Council chairmanship. With continued strong support from Secretary Kerry and President Obama, I am confident that I have the stature and authority to carry out my mission.

5. Would ratification of the UNCLOS treaty affect the way the United States is able to impact events in the Arctic?

Joining the Law of the Sea Convention remains a top priority for this administration. Melting ice in the Arctic is creating new risks, opportunities and responsibilities. As a party to the convention, the United States can best protect the navigational freedoms enshrined in the convention and fully secure its sovereign rights to the vast resources of our continental shelf beyond 200 miles from shore.

America and the Arctic

So where does this leave the United States? U.S. involvement in the Arctic up to this point has been mostly related to science, energy exploration, and bilateral and multilateral treaty negotiations through the Arctic Council. The first Arctic strategy of any consequence was issued by the George W. Bush administration in January 2009; there was no comprehensive Arctic vision before that time. Because the Obama administration has not issued its own strategy, the 2009 version—known as National Security Presidential Directive 66/Homeland Security Presidential Directive 25, or NSPD 66/HSPD 25—is the official Arctic policy of the United States. The document lays out in general terms what American goals are for the Arctic, touching on national security, the environment, energy resources, international cooperation and indigenous populations. In many ways, these mirror the official focus areas of the Arctic Council, whose chairmanship Washington first held from 1998 to 2000.

The Department of State is the lead agency on issues having to do with the Arctic due to its status as the home of the office tasked with Arctic Council relations. Many other agencies, however, including Commerce, Transportation, Defense, Energy, the Environmental Protection Agency and the National Science Foundation, work on Arctic issues under State’s direction. The Office of Ocean and Polar Affairs resides within State’s Bureau of Oceans and International Environmental and Scientific Affairs, and is led by the recently appointed first-ever Special Representative for the Arctic, retired Admiral and former Coast Guard Commandant Robert Papp. That office itself has four full-time employees dedicated to working on Arctic issues.

True, State has elevated the importance of Arctic issues in recent years. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and Secretary of the Interior Ken Salazar became the first U.S. cabinet officials to attend an Arctic Council ministerial meeting in 2011, and Secretary John Kerry has attended two in the intervening years. President Obama became the first sitting U.S. president to venture north of the Arctic Circle in August, when he attended the GLACIER conference on Arctic issues, organized by the Department of State, in Anchorage, Alaska. (Obama’s focus was on climate change.) The visibility is there, but what about resources and concrete actions?

One significant stumbling block is the U.S. failure—so far—to ratify the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. As a result, the United States is deprived of a voice in many of the forums where matters relating to the Arctic are discussed and decided on.

One significant stumbling block for the United States is the failure—so far—to ratify the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.

Voices of Dissent

In late August 2015, The New York Times made the following claim on its front page: “U.S. Is Playing Catch-Up in Scramble for the Arctic.” While focusing mostly on military assets, and particularly in comparison with Russia’s actions, journalist Steven Lee Meyers makes the case that the United States has not devoted enough resources to the Arctic, and that it is significantly behind the other Arctic nations and even China, Singapore and South Korea in many areas.

“We have been for some time clamoring about our nation’s lack of capacity to sustain any meaningful presence in the Arctic. … The United States really isn’t even in this game,” current Coast Guard commandant Admiral Paul Zukunft tells Meyers. There are other voices of dissent. Senator Lisa Murkowski of Alaska is a strong advocate for devoting resources and attention to the Arctic, and is the co-founder, with Maine Senator Angus King, of the Senate’s Arctic Caucus. In addition to her disagreements with President Obama’s environmental policies in the Arctic, she is dissatisfied with the lack of specificity and “no real path of action” in the administration’s pronouncements on the Arctic, most recently the 2014 Implementation Plan for the National Strategy for the Arctic Region. In response to what she sees as a lack of funding for Arctic priorities, Murkowski is said to be preparing to introduce an Arctic infrastructure bill.

Heather Conley, the noted Arctic expert at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, has expressed disappointment with the U.S. agenda for its Arctic Council chairmanship and wondered why there is not greater focus on more traditionally geopolitical issues in the Arctic. Climate change is all well and good, but in her words from a CSIS Commentary piece: “Tough, national decisions about Arctic readiness should have been made years ago and assessments must be made about the Arctic’s future security environment. There is not a moment to lose.”

In fact, it is a challenge to find someone outside of the administration who gives Washington a good grade on the Arctic. Even a 2014 Government Accountability Office report on Arctic issues found significant problems with coordination among the various agencies tasked with disparate parts of the Arctic portfolio and tied this directly to a lack of resources to devote to these issues. The GAO clearly identified the Department of State as the lead agency and provided a recommendation to improve coordination. State agreed; no follow-up report has been issued, so it’s impossible to know how much—or little—has been done to address the problems identified by the GAO.

What Is the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea?

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (often referred to as the Law of the Sea Treaty) was originally agreed to in 1982 and became binding in 1994.

The Encyclopedia of Earth defines UNCLOS as “the most comprehensive attempt at creating a unified regime for governance of the rights of nations with respect to the world’s oceans. The treaty addresses a number of topics including navigational rights, economic rights, pollution of the seas, conservation of marine life, scientific exploration, piracy and more.”

The treaty has been ratified by 167 parties; notably, the United States is not among them. In 2012, the last time a vote was attempted on the treaty in the Senate, enough Senators signaled their intention to vote against it that it could not gain the assent of two-thirds of the Senate. It therefore remains unratified.

The main arguments against the treaty are that it impinges on U.S. sovereignty, including through international dispute arbitration and imposition of binding rules.

It should be noted that there is significant support outside the Senate for ratification; for instance, within the military and the business community as well as among scientists.

UNCLOS is rapidly becoming more important in matters of the Arctic, its resources and land distribution. The continued U.S. failure to ratify the treaty will soon impinge on America’s ability to contribute to decisions on these issues through the acknowledged international frameworks.

What Next?

It will become increasingly important to tie the allocation of resources to the actions of other Arctic nations, specifically Russia. As Moscow becomes more emboldened in the high north, it will become a strategic imperative to have the capacity to respond diplomatically, not just militarily. The Department of State must have the financial and human resources required to respond to any kind of challenge that may arise in the Arctic. Those in Congress who support a stronger U.S. role in the Arctic must back up their words with the budgetary support that is required. Without the ability to enhance infrastructure such as port facilities in the Arctic or build more than the two recently announced new icebreakers, we risk falling behind.

More financial resources are one part of the solution, but the Department of State—as the designated lead agency on Arctic issues—can provide another part of the solution, as well. As U.S. interests in the Arctic change, it will become increasingly imperative to develop a cadre of Foreign Service officers and specialists who are experts in the diplomacy, politics and even science of the Arctic. The department needs to build up and maintain an in-house expertise on the issue that is not reliant on a succession of political appointees, special envoys and Schedule B scientific and technical advisers. The United States should ensure that the Arctic is a specific portfolio for one Foreign Service member in each of its embassies in the Arctic Council members’ capitals, as well as in Beijing. Such a group of in-house diplomats will be able to work on the inevitable issues arising from the ongoing melting of Antarctic ice and the future race for influence in that region.

Passing the proposed bill on the establishment of a Senate-confirmed ambassador-at-large for Arctic affairs would also raise the profile of the Arctic within the federal government. Having a special representative is a step up from earlier practice; but this issue will only gain in prominence in the future, and the bureaucracy should reflect that.

The United States is used to a leadership role on global issues, particularly those that affect us at home. The Arctic is such an issue. It affects our oceans, our energy future, the people of Alaska, our business and transportation sectors, and our diplomatic relations. Our Department of State and the Foreign Service can not only embrace that role, but excel at it.

Read More...

- Arctic Council (www.arctic-council.org)

- Russia expands its Arctic ambitions (Al-Jazeera, May 27, 2009)

- Arctic Region Policy (National Security Presidential Directive 66, Jan. 9, 2009)

- U.S. Is Playing Catch-Up With Russia in Scramble for the Arctic (The New York Times, Aug. 29, 2015)

- Implementation Plan for The National Strategy for the Arctic Region (www.whitehouse.gov, Jan. 2014)

- Better Direction and Management of Voluntary Recommendations Could Enhance U.S. Arctic Council Participation (Government Accountability Office, May 2014)

- United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (United Nations)