Taking Stock of Secretary of State Charles Evans Hughes

The 44th Secretary of State, a true statesman who displayed exemplary foreign policy leadership, deserves more recognition.

BY MAXWELL J. HAMILTON AND JOHN MAXWELL HAMILTON

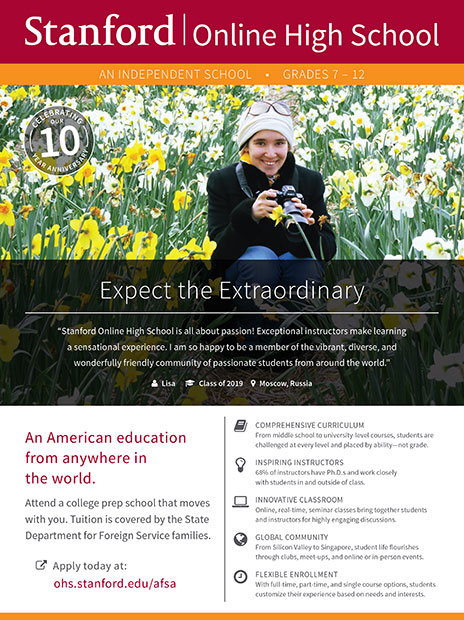

World leaders take a stroll during a recess at the World Disarmament Conference in Washington, D.C., in November 1921. Secretary of State Charles Evans Hughes is at the center.

U.S. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

On Nov. 12, 1921, pre-eminent statesmen from around the world assembled in Washington, D.C., to consider limiting the growth of the Great Power fleets. They were motivated by escalating tensions and the burgeoning costs of a global arms race. Two decades before Pearl Harbor, the Japanese government was already spending half its revenue on the military.

Hopes for an agreement were not high. No previous disarmament conference had succeeded; the First Hague Conference in 1899 had only acknowledged the desirability of arms limitations. But the calculus changed when U.S. Secretary of State Charles Evans Hughes rose to address the delegates seated at Continental Hall’s specially constructed walnut table.

Prior to the conference, Hughes had concluded that the only way to achieve success was with a bold proposal. This he sold to President Warren Harding, one of our least visionary presidents. He also convinced Harding of the wisdom of deviating from the standard practice of first floating the proposal to the foreign delegates in a closed session. Hughes feared this would give naysayers too much room for maneuver. Instead, he unveiled the specifics of the initiative in his speech welcoming the conference delegates.

A former Supreme Court justice who later became chief justice, Hughes made the case like the lawyer he was. He opened with lulling platitudes, and then stunned the audience by proposing a 10-year freeze on the size of each country’s fleet. Hughes named specific ships to be scrapped, beginning with those of his own country, before turning to Britain and Japan. In less than 15 minutes, said historian Thomas Bailey, Hughes had sunk more ships “than all the admirals of the world have sunk in a cycle of centuries.” The result was the Five-Power Treaty, (also known as the Washington Naval Treaty), signed on Feb. 6, 1922, which scrapped warships under construction and halted the production of larger warships for a decade.

Yet today, sadly, Hughes is all but forgotten, despite the many remarkable achievements during his distinguished career in public service. At the time of his death in 1948, at the age of 86, Hughes was regarded by many legal scholars as one of the two best chief justices of the Supreme Court (John Marshall was the other), a position he held from 1930 to 1941. He was an associate justice of the Supreme Court from 1910 to 1916 and a member of the Court of International Justice from 1928 to 1930.

His two terms as governor of New York (1907-1910) were marked by progressive legislation widely copied by other states. The muckraking journalist Ida Tarbell said at the time, “Charles E. Hughes is engaged in a passionate effort to vindicate the American system of government.” He was ahead of his time on laws relating to race, freedom of the press and women’s suffrage. Few Americans remember that Hughes was the Republican presidential nominee in 1916, losing by one of the narrowest margins in history. It was the only conspicuous failure in his career.

A poll of diplomatic historians carried out shortly after Hughes’ death named him one of the three best Secretaries of State after John Quincy Adams and William H. Seward. Although the only full biography of him—the two-volume Charles Evans Hughes by Merlo J. Pusey—is now nearly 65 years old, Hughes was lionized in his time. “His is the best mind in Washington,” wrote a journalist in a survey of Washington personalities after World War I, “to this everyone agrees.”

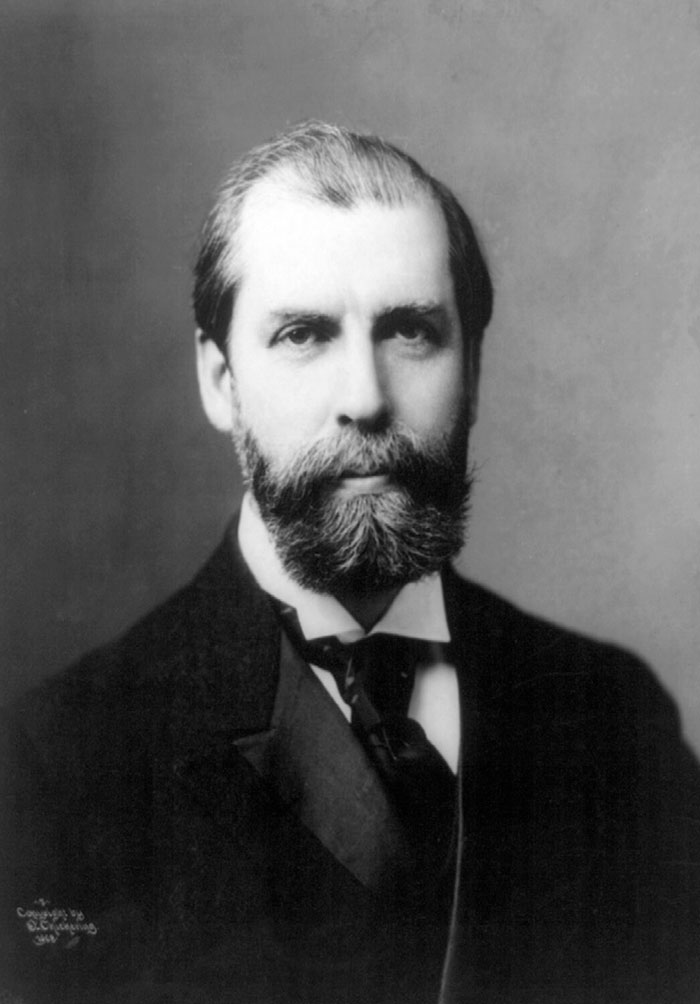

Hughes possessed a complicated personality, but he also had a remarkable ability to adapt to whatever job he took on. In private he was high-strung and, often due to overwork, anxious and self-doubting. He also was coldly objective and deliberate in his approach to issues. With his carefully groomed beard and aristocratic bearing, he had the daunting look of Jove. Hughes’ independence annoyed Theodore Roosevelt, who called him the “bearded iceberg.”

He preferred the company of his family over public ceremonies and chummy bourbon-laced gatherings with politicians. This suited him well as Supreme Court Chief Justice in the 1930s. Because his work did not require socializing, he only dined out on Saturday evenings. As Secretary of State, however, he made himself available night after night, to the point of personal exhaustion. Hughes relished the application of law, which made him one of the most successful lawyers of his generation. But he understood the special requirements of diplomacy, a profession that required compromises with multiple audiences to achieve larger objectives.

Skillful Leadership at Foggy Bottom

By the time Hughes became Secretary of State, on March 5, 1921, the United States had joined the ranks of the great powers—but most Americans remained isolationists. Reflecting that mood, the Senate had rejected outgoing President Woodrow Wilson’s proposal that the United States join the League of Nations.

Hughes initially took up that cause himself, but backed down when it became clear that he was unlikely to succeed and the fight would distract the administration from other urgent issues. As a second-best option, Hughes’ diplomats collaborated with League committees on such humanitarian issues as trafficking in women and children, relief and narcotics.

Because the Senate had also rejected the Treaty of Versailles, which formally ended World War I, Hughes crafted an agreement that used language from a 1921 congressional resolution that reserved to the United States the rights of all the victorious nations. He then incorporated language from the Treaty of Versailles defining just what those rights were, an adroit gambit that satisfied Germany and the Senate. At last, the war was officially over for the United States.

“His is the best mind in Washington,” wrote a journalist in a survey of Washington personalities after World War I, “to this everyone agrees.”

The Five-Power Treaty of 1922 was perhaps the greatest example of Hughes’ foreign policy leadership. His bold opening remarks generated public sentiment that pressured foreign governments to accept tough concessions on arms limitation. One observer commented that Hughes had spoken “not to the delegates assembled in Continental Hall, but to the whole world to focus public opinion before anyone else had a chance to play with it.”

After his speech, the Washington Naval Conference adjourned for three days, and during the recess Hughes’ words flew around the globe. Japanese correspondents cabled his entire speech to Tokyo at the cost of $1.50 a word. The London Daily Chronicle declared that the “world is in debt to the United States government for its broad humanity and incisive vigor.”

Contemporary accounts extol Hughes’ powers of concentration. He could memorize a speech after reading it a few times. In the months leading up to the Washington Naval Conference, he carefully studied naval data and mastered technical questions concerning tonnage, expenditures and armaments. He had understood that successful arms limitation could not focus on the naval needs of each power—a recipe for limitless expenditures that would not increase international security—but instead should focus on a proportionate reduction of the relative naval strength of each country.

With that in mind, Hughes devised a capital-ship ratio among the five powers—the United States, the United Kingdom, Japan, France and Italy—that guided the course of the negotiations. Diplomatic wrangling over the details of the agreement lasted 12 weeks, with Hughes and other delegates forced to make tough compromises. Due to French recalcitrance, Hughes was unable to extend the limitations on naval armaments to smaller vessels. But he succeeded where no one else had before: The world had its first arms control agreement.

Promoting Institutional Reform

Disarray at the State Department was another problem that confronted Hughes immediately. The department had been in urgent need of reform after drifting under Bainbridge Colby, President Wilson’s last Secretary of State. One of Hughes’ predecessors, Elihu Root, described the department as “in the condition of a virtual coma.”

Secretary Hughes threw his characteristic energy into institutional reform. “Every American should feel ashamed that any country in the world should have a better diplomatic organization than the United States,” Hughes said. “This is not simply a matter of national pride; it is a matter of national security.”

Hughes’ guiding principle was the importance of merit-based personnel decisions. Just as, while governor of New York, he had refused to appoint Republican Party hacks, as Secretary of State Hughes was determined to select qualified public servants. He frequently called himself “the only politician in the department.” To this end, Hughes derailed some of President Harding’s more egregious political appointments. Once, when Harding insisted on naming someone Hughes opposed, the Secretary coolly replied, “Of course you are at liberty to do so, if that is your decision.” Reluctant to override the judgment of his Secretary of State and risk his resignation, Harding withdrew the nomination.

Hughes asked outgoing Under Secretary Norman H. Davis to help him identify the best career officers for important posts, and he filled the under secretary position—then the second-ranking position in the department—with a succession of skilled career diplomats, including Joseph C. Grew, who served in the same position again at the end of World War II. Hughes also reorganized the department along geographic lines and appointed regional specialists to lead these divisions.

Most importantly, Hughes championed the reforms developed by Assistant Secretary of State Wilbur J. Carr, a career FSO who proposed merging the diplomatic and consular services. In 1919, Massachusetts Representative John Jacob Rogers had introduced Carr’s reform bill, but it languished in Congress. Hughes’ personal papers at the Library of Congress reveal his efforts to enlist Harding to win the support of key senators. In congressional testimony Hughes presented a compelling argument for the reform of a system that barred all but the wealthy from pursuing a diplomatic career. “It is entirely opposed to the traditions of this country, at least to the traditions which we profess to be desirous of maintaining,” Hughes testified, “to have a service which must of necessity, be largely recruited, if not altogether recruited, from those of independent means.”

The Rogers Act passed on May 24, 1924. The legislation established the Foreign Service as we know it today: It merged the diplomatic and consular branches of the State Department, set a uniform pay scale, and eliminated the need for private incomes, granted representation allowances for diplomats, and extended retirement benefits. By professionalizing the State Department, the Rogers Act opened the possibility of diplomatic service to a broader range of Americans, not just the independently rich.

Congress and the Press

Charles Evans Hughes, 1908.

E. Chickering and Co. of Boston / Wikimedia Commons

Despite the view of Hughes as a whiskered iceberg, he engaged legislators in highly effective ways. As part of his strategy for the naval conference, for instance, Hughes persuaded President Harding to appoint Senator Henry Cabot Lodge (R-Mass.), chairman of the Foreign Relations Committee, and Senator Oscar Underwood (D-Ala.), the Senate minority leader, to the U.S. delegation. This avoided Woodrow Wilson’s mistake of excluding Congress from the Paris Peace Conference deliberations. Only one senator voted against the naval treaty.

In 1922 the Senate introduced a bill to unilaterally settle Germany’s World War I reparations payments to the United States using German assets seized during the war. American preferences for high tariffs, which Hughes supported, contributed to Berlin’s repayment problems. (This was one of the few black marks on his record.) Nevertheless, he vehemently objected to the proposed legislation as contrary to international norms and suggested instead creating a special commission to negotiate repayment with Germany.

Even though establishment of such a commission did not require Senate consultation, Hughes met with Senator William E. Borah (R-Idaho), a leading isolationist voice in Congress, to explain his plan, and carefully laid out the legal precedents. Borah was convinced, and Congress did not pursue the heavy-handed reparations legislation. As a result, the commission reached a satisfactory agreement with Berlin.

And so it went throughout his tenure as Secretary of State. Hughes’ willingness to consult and inform Congress was a key to his success. By one estimate, the Senate approved all but two of the 69 treaties submitted during Hughes’ tenure.

Another break from the pattern of the Wilson administration was Hughes’ handling of the Washington press corps, which had become a demanding, professionalized force crucial to winning—or losing—public opinion. Whereas President Wilson and his Secretary of State, Robert Lansing, alienated journalists with their disdain and misleading statements, and often worked at cross purposes with each other in their pronouncements, Hughes “was the most satisfactory source of international news in the government in our time,” wrote Fred Essary, a Baltimore Sun reporter who had been a fervent supporter of Wilson.

Hughes met twice a day with journalists. He was candid and clear. After Harding misstated an aspect of the Washington Naval Conference negotiations, Hughes tasked one of his assistants to make a verbatim report of all foreign policy statements at White House press briefings to ensure the administration spoke with one voice.

A True Statesman

Whether he was championing state regulation of public services as governor of New York, or pressing unsuccessfully for the establishment of a Permanent Court of International Justice as Secretary of State, Hughes believed progress could be achieved incrementally. He supported the gradual evolution of international behavior toward “greater rationality and order.” He was skeptical of attempts to outlaw war, considering armed conflict an unavoidable condition of international relations. Yet he believed war could be limited through the development of international laws and institutions to arbitrate disputes. In his finest moment at the Washington Naval Conference, Hughes made a realistic assessment of what was possible under the circumstances and jettisoned unworkable provisions—such as the inclusion of auxiliary naval craft—to achieve a limited agreement.

Arthur Balfour, the highly respected British delegate to that conference, called Hughes “the most dominating figure I have ever met in public life.” The lessons of his statesmanship still resonate nearly a century later.

Back in the 1920s, like today, the United States faced questions about its proper role in an evolving international system. Secretary of State Hughes effectively managed the president, Congress and public opinion to find common ground on challenging foreign policy questions. He seized opportunities to shape a new world to America’s advantage, but he understood progress would take years if not decades. Hughes was unusual not only because he was capable of decisive action, but also because he had the judgment, patience and wisdom to know when U.S. leadership could make a difference.

Read More...

- Biographies of the Secretaries of State: Charles Evans Hughes (U.S. Department of State Office of the Historian)

- Charles Evan Hughes (Merlo J. Pusey)

- Notes on People; Opinion Poll (The New York Times, Nov. 26, 1981)

- The Department of Peace: Secretary Hughes Outlines to Business Convention (American Consular Bulletin, June 1922)