‘A Love Letter to Diplomacy’: A Q&A with David Holbrooke

Talking Points

On Nov. 2, 2015, HBO released the film “The Diplomat,” the story of Richard Holbrooke as presented by documentary filmmaker David Holbrooke, the ambassador’s eldest son.

For those of us working at the State Department during Holbrooke’s time, the film is powerfully evocative. I, myself, can’t help recalling one oddly quiet, all-night shift in the Operations Center in 1998, when we wrote a spoof log that included an entry that went something like this: 1:30 a.m., Richard Holbrooke called, just to say goodnight.

It was funny because it was the polar opposite of the Richard Holbrooke who called the ops center many times a day and often through the night—brusque, demanding, consumed, all business and, in fact, critically important to all that was going on with the Balkans and the Kosovo crisis of the time.

We never thought then about the fact that Richard Holbrooke had kids, that he probably did say goodnight, when possible, to those he loved. So it was a particular honor to be able to talk to David Holbrooke about his father, as I did in a recent email exchange reproduced here.

—Shawn Dorman, Editor

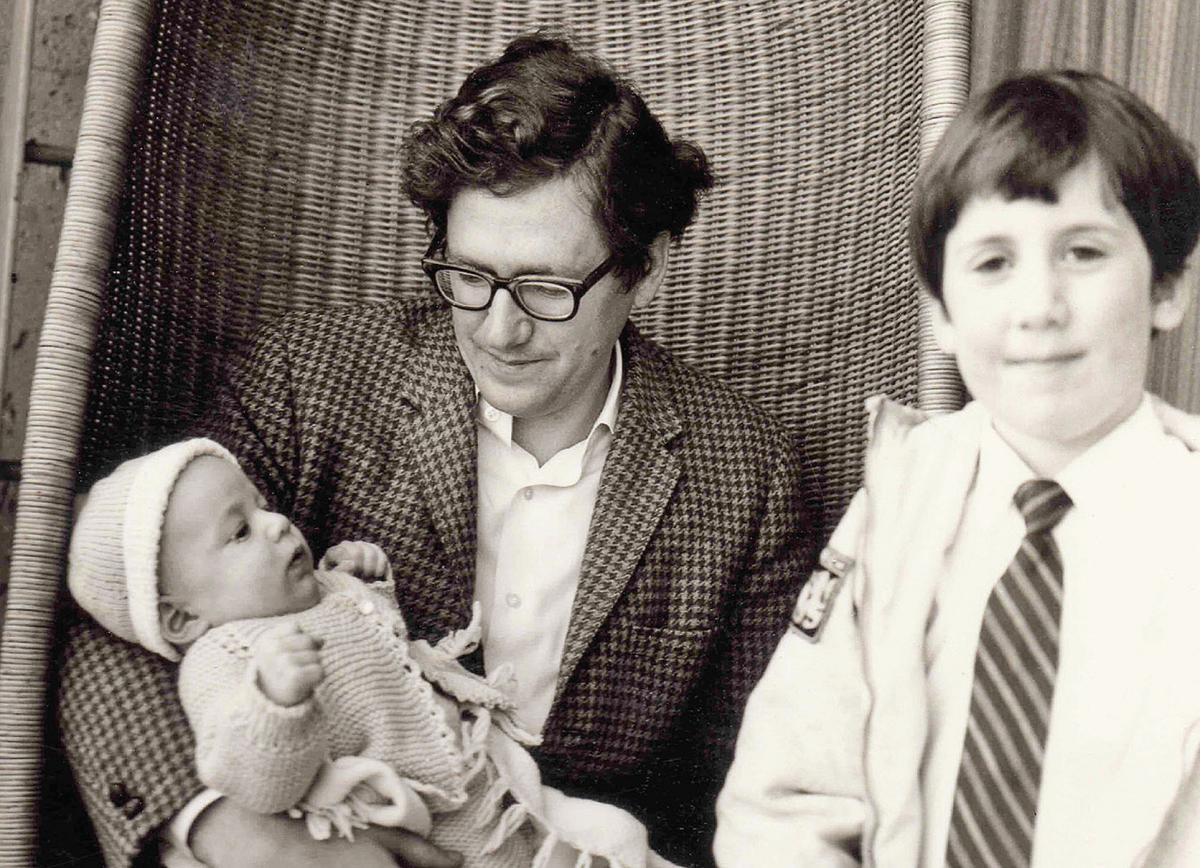

Richard Holbooke with his children, David (at right) and Anthony.

Pete Souza / Courtesy of HBO

Foreign Service Journal: Can you give us a brief synopsis of the film?

David Holbrooke: “The Diplomat” looks at the life and career of my father Ambassador Richard Holbrooke. It is my effort to retrace his own personal and professional journey. Because he was so immersed in the world of foreign policy, the film is also about the history of American diplomatic efforts from Vietnam to Afghanistan.

FSJ: Why did you decide to do this project?

DH: My father died suddenly in December of 2010 and when we memorialized him at the Kennedy Center a month later, I sat on stage with Presidents Obama and Clinton, Hillary Clinton and other major figures. Listening to their stories of his life, I realized my father was an historical figure, something that I hadn’t fully appreciated before that moment.

I set out on this challenging journey for several reasons. I knew I had to get to know him better and felt he had something more to say. I also wanted my children to have a better understanding of their grandfather who they didn’t see enough. My other hope was to inspire young people to want to go into the Foreign Service.

FSJ: What was it like growing up as the son of Richard Holbrooke?

DH: I think any kid growing up in an abnormal situation thinks it is normal to a point, so to be meeting heads of state and other dignitaries seemed par for the course. But he was always on the go and rarely around to be a father in a regular way. He did like to do fun things; we would routinely go to movies and theater, and he also loved video games—which is funny to think about now.

Of course, I had a good sense of his work from the news, but when I look back, all I understood were the broad strokes. He never really engaged with my brother Anthony and me about what he was doing. What we learned, we picked up from overhearing his conversations on the phone.

Now, after spending four years making the film and spending time in the places he worked with friends, staff and journalists, I have come to appreciate the fine details of the craft of diplomacy and how challenging it is.

While my father had enormous respect for the U.S. military, he did not feel they should be setting political strategy in Afghanistan or, really, anywhere else. In Vietnam, the military took the lead, and that didn’t turn out so well.

FSJ: While he was a great diplomat, your father was the first to admit he did not meet most people’s definition of “diplomatic.” Do you think his personal style was better suited to some regions (Balkans) than others (Afghanistan)?

DH: Well, we considered calling the film “Undiplomatic.” I do think he felt a lot of the niceties of the craft were unnecessary, but making sure the interpersonal dynamics worked was essential to him. He once said, “diplomacy is a lot like jazz”—and I think for him a key element was being able to listen and then adapt and improvise to make sure the desired results were achieved.

In Bosnia, that was tricky as hell, but he was able to achieve it because Serbian President Slobodan Milosevic understood toughness and force, two things my father used to his negotiating advantage. In Bosnia, there was also a real effort to make sure that the approach was diplomacy backed by force, rather than the other way around.

Afghanistan was a vastly different situation. Afghan President Ashraf Ghani says in the film that my father pushed former President Hamid Karzai too far: “He could browbeat Milosevic, but you can’t browbeat an Afghan.” I am not sure my father fully understood how his tactics and style needed to be changed for this part of the world; he really struggled with it.

FSJ: What do you think your father would want Foreign Service members to understand about what he faced in his role as Special Representative for Afghanistan and Pakistan?

DH: I think he was most proud of creating the deeply impressive SRAP team of people from all over the government. That diversity of backgrounds allowed them to work more dynamically as a group on this one big thorny problem.

It is no secret that he had a rough go of it in the Obama administration. Yet he was eminently loyal to President Obama and very much believed in the chain of command. It was very clear to his staff that they had to respect this, despite their own frustration with the White House.

He was looking for any opening to advance diplomatic relations between Afghanistan and Pakistan. When I interviewed Secretary Clinton, she mentioned the Transit Trade Agreement that he helped broker and pointed out that he was enormously excited about this fairly small deal. He felt that any progress and agreements, no matter how minor, could lead to bigger ones and that you had to celebrate these accomplishments.

I would hope that Foreign Service members would be moved by his perseverance. I also hope they will be inspired by his creativity in finding solutions.

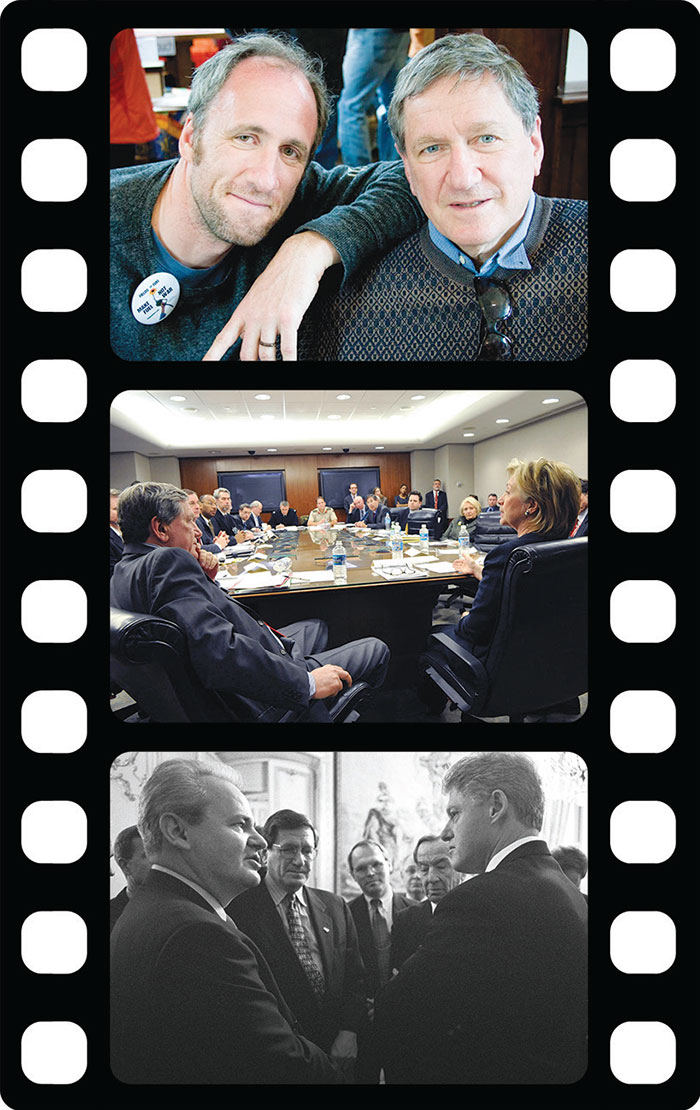

TOP: David and Richard Holbrooke in a casual moment.

Photo Credit: Jodi Cobb / Courtesy of HBO.

MIDDLE: Ambassador Holbrooke and Secretary of State Hillary Clinton at work.

Photo Credit: U.S. Department of State / Courtesy of HBO.

BOTTOM: President Bill Clinton talks with Serbian President Slobodan Milosevic in Paris on Dec. 14, 1995. Between them are, left to right, Ambassador Richard Holbrooke, FSO Christopher Hill and Secretary of State Warren Christopher.

Photo Credit: Clinton Presidential Library / Courtesy of HBO.

FSJ: Your father was critical of the U.S. military’s increasing role in setting U.S. policy in Afghanistan. Was his a wholesale rejection of military solutions, or did he indicate there were situations in which a more prominent military role was appropriate?

DH: The film’s big geopolitical theme that runs through all three segments—Vietnam, Bosnia and Afghanistan—is whether American foreign policy should be formed by the diplomats or the generals.

While my father had enormous respect for the U.S. military, he did not feel they should be setting political strategy in Afghanistan or, really, anywhere else. In Vietnam, the military took the lead, and that didn’t turn out so well. In Bosnia, Strobe Talbott, Deputy Secretary of State during the Clinton administration, said the policy was “diplomacy backed by force.” That is one of the key lines in the film and an essential approach.

In Afghanistan, my father was intended to be the civilian counterpart to General Petraeus, but it was a very tricky relationship. My father would say that Petraeus had more planes than he had phones, and that was enormously challenging; but more so, he and other diplomats (including Hillary Clinton) simply didn’t have the same access to the president that the generals had.

FSJ: What were your father’s biggest frustrations with diplomacy as a practice and process?

DH: My father was enormously frustrated by the lack of creativity and imagination of some of the people he worked with and for. He felt their vision was too small or, worse, too self-serving. While he had sharp elbows and a considerable ego, he also felt that those traits were ultimately in the service of the people he had to help.

He loved the Foreign Service and believed in its potential as an enormous force for positive change. He also felt it could be hidebound. For himself, he knew the best way to advance was to actually leave the government and get outside experience to bring back.

I have shown the film to a lot of diplomats. It registers with them deeply. Their takeaway is often that they need to do more, take bigger risks and, as one said to me, “Think about what Richard Holbrooke would do.”

FSJ: How would you describe your father’s legacy?

DH: Of course, the peace that remains in Bosnia is a huge part of his legacy; but it is a tenuous peace, and I hope the film gets Americans to pay attention to the region again, especially since we are at the 20th anniversary of Dayton. His legacy in Kosovo is also huge. When I was there, people came up to me all the time to thank me for his work.

And as I left the country, the border guard looked at my passport and asked, “Are you son of Richard Holbrooke?” I said yes, and he handed my passport back, shook my hand and said, “He’s number one here.”

The last credits in the film read: “Dedicated to the next generation of diplomats.” A friend of mine who works in the State Department saw the film at Tribeca and said it was “a love letter to diplomacy.” There is a lot of truth to that.

There are countless films about making war, but so few about making peace. After every screening, people gather around me to talk about it. Many are older and have enjoyed this look back at the global history that has paralleled their lives; but there are also always young people bouncing up and down, with a gleam in their eye, who want to tell me how much my father’s story inspired them. That makes it all worth it, as I think he would have wanted that to be his legacy as much as anything.