A Gift of Peace

The popular quest for freedom and self-determination brought down the Berlin Wall, ending an era.

BY JAMES D. BINDENAGEL

Berlin Wall Photo by James Talalay

When the Berlin Wall fell on Nov. 9, 1989, the world sighed with relief that this historic event happened peacefully. We were all elated. German and European unity was a gift of peace to the trans-Atlantic partnership—the United States, Canada and Europe—that had constituted a vast zone of peace, prosperity and democracy for most of the last 70 years.

Today the 1989-1990 revolutions in Europe seem like such a historical given that it is hard to imagine the truth: In 1989 few envisioned that developments in the socialist world would soon accelerate so dramatically. Early that year East German head of state Erich Honecker had predicted the Berlin Wall would last for 100 years. Western politicians may have given speeches about the yearning for freedom in Central and Eastern Europe. But they, too, had no real idea of how strong that yearning among people long conditioned to suppress their hope for freedom would prove to be.

There were three critical moments in the momentous transformation that took place during that year. First was the “Miracle of Leipzig,” on Oct. 9, when Germans in the German Democratic Republic found the courage to demonstrate their demand for freedom to travel. Second was the fall of the Berlin Wall one month later, on Nov. 9, when that courage was joined with self-determination as East Berliners took to the streets and challenged the border guards at the Bornholmer Strasse checkpoint. And, finally, just a year later, East Germany’s freely elected parliament voted, on Oct. 3, 1990, to join the two Germanys together.

At the time, I was serving as the deputy chief of mission of the U.S. embassy in the GDR, in East Berlin. Here is my eyewitness report of those earthshaking events.

Prelude: The Miracle of Freedom

It all began slowly in the summer of 1989, after the May 7 municipal election results were contested by East Berliners such as civil rights activist Thomas Krueger. Change was in the air. On June 4 the Chinese government massacred democracy demonstrators in Tiananmen Square in Beijing. Shortly afterward, the Honecker government received Chinese Premier Li Peng, known as the “Butcher of Beijing” for his role in that massacre, in an act of solidarity with the Chinese crackdown against “counter-revolutionaries.”

In August, Honecker, general secretary of the ruling Socialist Unity Party (SED), was ill; so his second-in-command, Egon Krenz, traveled to China. Krenz’s subsequent comment on the Chinese action—“Etwas getan worden, um die Ordnung wiederherzustellen” (Something had to be done to uphold order)—became known as the China Solution. East Germans understood. The fear generated by the Honecker government fed a flood of East Germans from the GDR that had picked up during the year, young people from my Pankower Catholic Church among them.

It all began slowly in the summer of 1989, after the May 7 municipal election results were contested by East Berliners.

West German Foreign Minister Hans-Dietrich Genscher and Interior Minister Rudolf Seiters intervened with the Honecker government to allow East Germans in Prague to immigrate to West Germany by way of the West German embassy. By the end of September, trains carrying fleeing East Germans crossed from Prague through Dresden and on to West Germany. Though still standing, the Berlin Wall was being circumvented.

The Honecker government then imposed a visa requirement for travel to Hungary and Czechoslovakia. As a result, on Oct. 4, 1989, some 18 East Germans sought asylum in the U.S. embassy in East Berlin. Only with the assistance of Wolfgang Vogel—a famous East German spy-swapping lawyer and Erich Honecker’s personal attorney—could we at the embassy obtain passes for them to West Berlin before the GDR’s 40th anniversary celebrations began three days later.

USSR President Mikhail Gorbachev’s visit to East Berlin as guest of honor at the Oct. 7 celebrations was fraught. The choice between Gorbachev’s perestroika and glasnost and Honecker’s expected repression of demonstrators was stark. In a public encounter during the visit, Gorbachev was quoted as saying: “Life punishes those who come too late.” It was widely understood as a warning to Honecker.

After Gorbachev departed East Berlin, the crackdown began. I was at the Gethsemane Church that evening, a church where protesters met to demand freedom for friends arrested for demonstrating. Demonstrations for “freedom and the right to travel” had become a regular and growing feature of life in East Berlin and other cities. As the evening wore on, the police moved in, hauling off thousands of demonstrators to holding areas for subsequent arrest.

In Leipzig, on Oct. 9, the regular Monday night vigil at the Nikolaikirche was the focus of attention. Pastor Christian Fuehrer saw his church half-filled with Stasi agents as the tension grew over the continued crackdown. Three SED members had met that afternoon with Gewandhaus Orchestra Maestro Kurt Masur, who was highly regarded by the people and the government, to deal with the increased police presence and the expected violence. The fear was palpable. Masur saw the events as revolutionary, and in an October 2010 interview with Der Spiegel recalled what he had thought that afternoon: “When 17- and 18-year-olds said goodbye to their parents that day, it was like they were heading off to war. But everyone had had enough. All of them—all 70,000 of them—were able to overcome their fears.”

As it happened, the Leipzig SED officials, the police chief and Kurt Masur made the decision to call for “keine Gewalt” (no violence). It was a choice between crackdown and perestroika, between Honecker and Gorbachev. The 70,000 demonstrators, seen only from the video of one camera smuggled in under the Honecker media ban, marched that night without violence. The brave souls of Leipzig repeated their act of courage on Oct. 16, and two days later Egon Krenz led the SED Politburo decision to remove Erich Honecker as the SED general secretary and GDR head of state.

The Berlin Wall for 100 Years

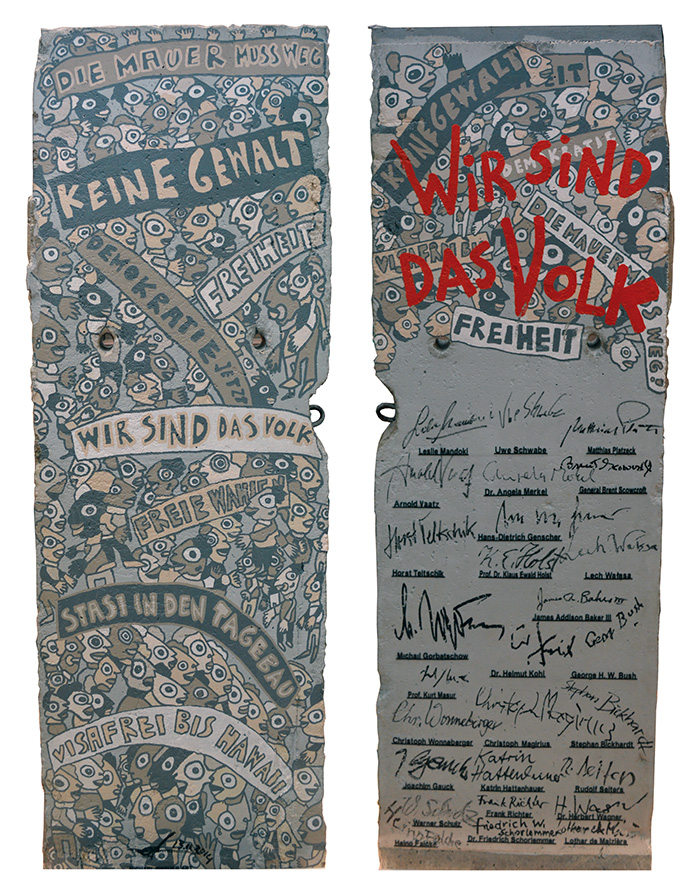

Pieces of the Berlin Wall that are now part of the U.S. Diplomacy Center’s permanent collection.

AFSA / Dmitry Filipoff

On Nov. 9, 1989, there was no sign of revolution. Sure, change was coming—but slowly, we thought. After all, the Solidarity movement in Poland began in the early 1980s. I spent the afternoon at an Aspen Institute reception hosted by David Anderson for his new deputy director, Hildegard Boucsein, with leaders from East and West Berlin, absorbed in our day-to-day business. In the early evening, I attended a reception along with the mayors and many political leaders of East and West Berlin, Allied military commanders and East German lawyer Wolfgang Vogel. Not one of us had any inkling of the events that were about to turn the world upside down.

As the event was ending, Wolfgang Vogel asked me for a ride. I was happy to oblige and hoped to discuss changes to the GDR travel law, the target of the countrywide demonstrations for freedom. On the way, he told me that the Politburo planned to reform the travel law and that the communist leadership had met that day to adopt new rules to satisfy East Germans’ demand for more freedom of travel. I dropped Vogel off at his golden-colored Mercedes near West Berlin’s shopping boulevard, Ku’Damm. Happy about my scoop on the Politburo deliberations, I headed to the embassy. Vogel’s comments would surely make for an exciting report back to the State Department in Washington.

I arrived at the embassy at 7:30 p.m. and went directly to our political section, where I found an animated team of diplomats. At a televised press conference, government spokesman Guenter Schabowski had just announced the Politburo decision to lift travel restrictions, leaving everyone at the embassy stunned. East Germans could now get visitor visas from their local “People’s Police” station, and the East German government would open a new processing center for emigration cases. When an Italian journalist asked the spokesman when the new rules would go into effect, Schabowski fumbled with his papers, unsure—and then mumbled: “Unverzueglich” (immediately). With that, my Vogel scoop evaporated.

At this point, excitement filled the embassy. None of us had the official text of the statement or knew how East Germans planned to implement the new rules. Although Schabowski’s declaration was astounding, it was open to widely varying interpretations. Still dazed by the announcement, we anticipated the rebroadcast an hour later.

At 8 p.m., Political Counselor Jon Greenwald and I watched as West Germany’s news program “Tagesschau” led with the story. By then, political officer Imre Lipping had picked up the official statement and returned to the embassy to report to Washington. Heather Troutman, another political officer, wrote an on-the-ground report that the guards at Checkpoint Charlie were telling East Germans to get visas. Greenwald cabled the text of Schabowski’s announcement to Washington: East Germans had won the freedom to travel and emigrate.

As the cable arrived in Washington, I called the White House Situation Room and State Department Operations Center to discuss the report and alert them to the latest developments. I then called Harry Gilmore, the American minister in West Berlin.

“Harry,” I said, “it looks like you’re going to have a lot of visitors soon. We’re just not sure yet what that rush of visitors will look like.”

That the night of Nov. 9 remained peaceful was not only due to the Harald Jaegers and Tom Brokaws. In faraway Moscow, the president of the Soviet Union had also made courageous decisions.

A Rush of Visitors

We assumed that, at best, East Germans would start crossing into West Berlin the next day. In those first moments, the wall remained impassable. After all, these were Germans; they were known for following the rules. Schabowski had announced the visa rules, and we believed there would be an orderly process. East Germans, however, were following West German television coverage, as well. And, as it turned out, they decided to hold their government to its word immediately.

I headed home around 10 p.m. to watch events unfold on West German television. On my way to Pankow, I was surprised by the unusual amount of traffic. The “Trabi,” with its two-cycle engine and a body made of plasticized pressed-wood, spewing gas and oil smoke, was always in short supply. Perhaps one of the most striking symbols of East Germany’s economy, those iconic cars now filled the streets despite the late hour—and they were headed to the Bornholmer Strasse checkpoint. Near the checkpoint, drivers were abandoning them left and right.

Ahead of me, the blazing lights of a West German television crew led by Der Spiegel reporter Georg Mascolo illuminated the checkpoint. The TV crew, safely ensconced in the West, was preparing for a live broadcast. Despite the bright lights, all I could make out was a steadily growing number of demonstrators gathering at the checkpoint. From the tumult, I could faintly hear yells of “Tor auf!” (Open the gate!) Anxious East Germans had started confronting the East German border guards. Inside the crossing, armed border police waited for instructions.

Amid a massive movement of people, fed by live TV, the revolution that had started so slowly was rapidly spinning out of control. The question running through my mind was whether the Soviet Army would stay in its barracks. There were 380,000 Soviet soldiers in East Germany. In diplomatic circles, we expected that the Soviet Union, the military superpower, would not give up East Germany without a fight. Our role was to worry—the constant modus operandi of a diplomat. But this time, our concern didn’t last long.

When I arrived home around 10:15 p.m., I turned on the TV, called the State Department with the latest developments, and called Ambassador Richard Barkley and then Harry Gilmore again: “Remember I told you that you’d be seeing lots of visitors?” I said. “Well, that might be tonight.”

Just minutes later, I witnessed on live television as a wave of East Berliners broke through the checkpoint at Bornholmer Strasse, where I had been just minutes earlier. My wife, Jean, joined me, and we watched a stream of people crossing the bridge while TV cameras transmitted their pictures around the world. Lights came on in the neighborhood. I was elated. East Germans had made their point clear. After 40 years of Cold War, East Berliners were determined to have freedom.

The question running through my mind was whether the Soviet Army would stay in its barracks. There were 380,000 Soviet soldiers in East Germany.

The Other Side of the Story

In a 2009 Der Spiegel interview on the 20th anniversary of the Berlin Wall’s fall, Lieutenant Colonel Harald Jaeger gave his account of what had happened at the border crossing in the crucial moments before he made his fateful decision to grant passage. As Col. Jaeger explained, he had “spoken repeatedly to all officers in charge that evening, on the street, but also in his office. They demanded: ‘Harald, you’ve got to do something!’ I said: ‘What am I supposed to do? Should I let the GDR citizens leave? Or should I give the order to open fire?’ I wanted to hear what they thought. They stood together in my office, and I wanted them to tell me what I should do. ‘It’s up to you, you’re the boss,’ they said.” He acted.

I learned the other part of the Jaeger story a few months after that historic night. Some of the first people who had shown their GDR identification cards to the border guards to get across to the West had had a GDR exit visa stamped on the cardholder’s photo, which in effect invalidated the ID card. Jaeger “expelled” those first people crossing the checkpoints, thus ridding East Germany of dissidents. Evicting them was a fitting and expedient solution: The guards had tried to save East Germany from its discontented citizens by throwing the rascals out of the country. The rest of the story played out on live television.

Tom Brokaw broadcast to America and the world. German television reported to West and East Germans alike. East Germans saw the open Berlin Wall and hundreds of their fellow citizens fleeing west. They could not see the new rules, but Tom Brokaw and his fellow journalists created facts on the ground. Worried about the GDR and not trusting their government to give them visas, East Germans decided on the spur of the moment to go on their own to the checkpoints.

The newly announced visa requirement gave them the window, and they tested it. They poured into West Berlin thinking the opening would not last, that this was their only chance to taste freedom. Some expected to return home. Others hopped into their Trabis and drove many miles to get to Berlin in time to cross and not miss the only chance in their life they would have to visit West Berlin.

The End of the Old Order

The fall of the Berlin Wall is for the East Germans what the storming of the Bastille 200 years ago was for the French: the end of the old order and the end of an era. The East German people mustered the courage to storm the wall that had imprisoned them for decades, thus discovering the secret of freedom. They took their future into their own hands. Four months later, on March 18, 1990, they elected a democratic government, headed by Prime Minister Lothar de Maiziere, who led the parliamentary decision for accession to the West German constitution and, therefore, German unity on Oct. 3.

On that November night, however, it was not only the people of the GDR who embraced freedom with courage. That the night of Nov. 9 remained peaceful was not only due to the Harald Jaegers and Tom Brokaws. In faraway Moscow, the president of the Soviet Union had also made courageous decisions. Mikhail Gorbachev’s decision not to send his soldiers to restore Soviet control over East Germany was the critical step that made the revolution peaceful; that, followed by the East German decision not to carry out the shoot-to-kill order to defend the border, led to peaceful German reunification and European unity.

We must not forget the lessons learned from the Peaceful Revolution of 1989. Indeed, they seem more relevant today than ever before.