From the FSJ Archives: The World of 1953 and Iran

The United States is a relative latecomer to the politics of the Middle East, much of which derives from European colonialism, as this retrospective on Iran from 1980—already more than three decades past—shows.

BY ROY M. MELBOURNE

President Harry S. Truman and Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh of Iran during the latter’s visit to Washington, D.C., in October 1951.

U.S. National Archives and Records Administration / Abbie Rowe

The movement of great forces, while given definition by the vertebrae of power politics, has, since World War II, transformed the earth in a fashion that old historical maps could never convey. The world of 1953, already distant from today, was part of that great change.

Globally the Cold War raged, raised to an all-out struggle by Korea, still without an armistice. A malignant senator had convinced his public that China was lost because key public servants were communist dupes, if not crypto communists. Despite war losses, communist states were thought making a good recovery, helped by indigenous resources and a crucial, short-run advantage of centralized priorities direction. Strategically centered, revolutionary communism was regarded as monolithic and as pressing against its worldwide frontiers. A strong America was the keystone of the free world (there was no credible Third World); it was a partner in a threatened NATO alliance not yet four years firm, while Western Europe and Japan were just finding their feet.

In the Mideast there were two coherent, sizable states: the tough kernel of republican Turkey, being buttressed by America against Soviet demands, and the new revolutionary military government of Egypt. Dynamic Israel was a newcomer, while the others were either colonially plotted land tracts designated as countries or old feudal societies. Iran was a mutant.

A geographic plateau, a long distant culture, Shia Islam, and the shah as a focal symbol, served to give an identity to Iran’s core, half the population. The rest included disparate elements sharing some of these features, but stretching, among others, from the Kurds of the northwest and the Qashqais of the south, to the Baluchis of the southeast. Iran, long buffeted by the Anglo-Russian rivalry, had lost significant territories to Russia and in the south, Khuzistan, had seen the British run the great oil fields and refinery essentially for their own benefit.

The country had once been divided (1907) into spheres of influence between Russia and Great Britain and militarily between them during the urgencies of World War II. Thereafter British troops left, but it took great American pressure at the United Nations and some Iranian guile to impel the Russians to desert their puppet Azerbaijan regime and evacuate the country in 1946. A 1921 treaty, however, could give them a handle to return if this looked promising. Then, too, a secret clause of the 1939 Hitler-Stalin pact revealed ultimate Soviet aims by giving that country a free hand south in the direction of the Persian Gulf. This artery was seen by the West as the oil jugular of the free world and of nascent NATO.

Nevertheless, accumulated popular resentments toward foreign domination erupted over the issue of Iran’s oil. The highly visible British controlled the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, divided between British government and private ownership, and refused to increase Iran’s oil royalties at a time when the country was the world’s largest oil exporter. Turbulence took over, and, when the smoke cleared, emotional nationalism was embodied in the 1951 coalition government and unilateral uncompensated oil nationalization was its result. The Iranian-British standoff featured a boycott of Iranian oil and deepening financial depression for Iran. To international concern that the deteriorating situation gave fertile scope for communist subversion, Iran’s eccentric elderly prime minister [Mohammad Mosadeq] merely replied, “Too bad for you.” Time magazine thus started 1952 by naming him its man of the year. The caption: “He oiled the wheels of chaos.” The old man was delighted.

Iranian politics by 1953 continued to revolve around the twin pillars of nationalism and monarchy. The shah had not disowned the emotional xenophobia arising from the oil crisis. Prime Minister Mosadeq, controlling the Majlis, or parliament, had taken care to govern in the name of the shah and not to challenge openly his popular position as a traditional symbol of stability and, despite his youth, as a father figure. …

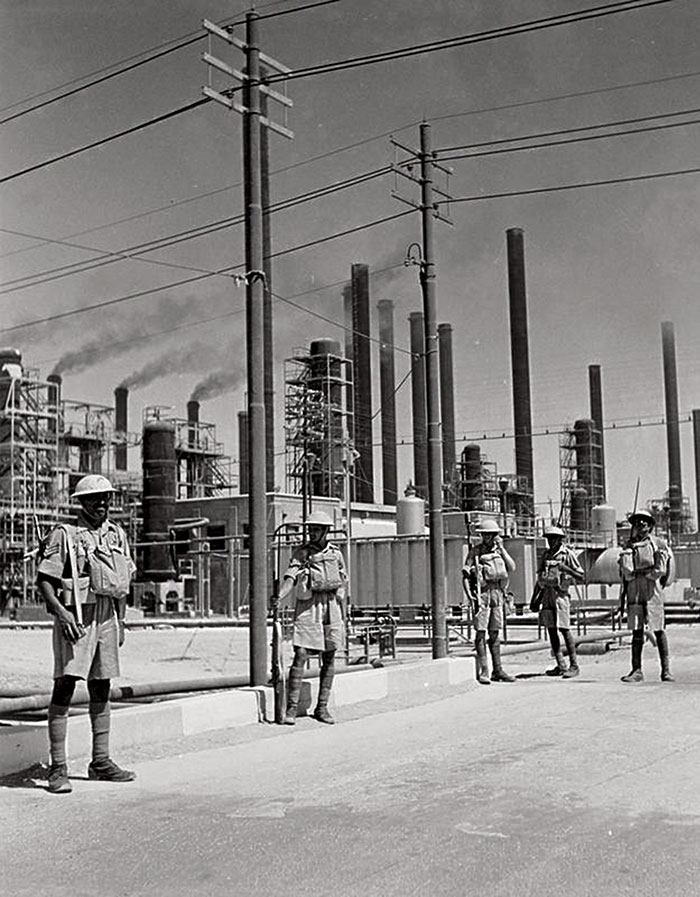

Oil Politics

During World War II British troops attacked the island of Aradian on the River Shatt-el-Arab, at the head of the Persian Gulf, to gain control of a large oil refinery belonging to the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company. Indian troops were landed from assault ships from the quayside, and they attacked the Iranian strong points in the refinery. Here, Indian riflemen stand guard at the refinery.

U.K. Imperial War Museum / Keating

When Iranian oil nationalization came, the AIOC believed that it had an effective weapon in an oil boycott, supplemented by foreign court challenges if any distributor dared run the gauntlet. This proved true. Meanwhile, other gulf states were raising production and servicing Iran’s old markets. The desired implication in those halcyon oil surplus days was that the new National Iranian Oil Company might have no place to go. For the Americans, however, the oil impasse, embodying Iranian nationalist frustrations and Britain’s desperate need for foreign exchange, was too important an economic, no, strategic, question to fester untended.

Before the issue exploded, the United States had confined itself to fruitlessly urging the British to be more forthcoming on royalties and other disputed matters, warning of the heavy consequences. To starve out the Iranian government and economy was similarly discouraged. When these courses jelled as policies, however, the economists, Americans included, made solemn periodic assessments on when Iran would have to capitulate. Successive crucial dates passed and the National Front, although frayed, was still there. The give in Iran’s underdeveloped economy was consistently underrated. There was not much distance to fall.

After the death of Foreign Secretary [Ernest] Bevin, the Attlee Labor government was on unsure ground with his successor, the mediocre Herbert Morrison. Whitehall belatedly recognized that the problem was too serious to be left to the chairman of the AIOC. British embassy personnel also were gradually changed. However, it was not really until the return of the power of [Winston] Churchill and [Anthony] Eden that Iran was moved to the political front burner.

Along with their economic strategy, the British had to recognize the concerns of their ally and, in hopeful or pessimistic expectations, approve American endeavors as middleman to find a compromise. Washington initially was reluctant to consider the oil issue as anything but an economic problem and resisted the indicators that it was basically a political question. The United States, at any rate, had the confidence of the Iranians, and thus embarked in 1951 on a persistent refuse-to-be-discouraged line, searching for a magic formula. This was punctuated by diverse visitors to Tehran for discussions with Mosadeq and his principal advisers. American senior statesmen, leading financial experts, oil company presidents, politicians, and a variety of scavenging personalities marked the procession. There was, of course, a large Tehran foreign press colony.

Shrewd Iranian politician that he was, Mosadeq talked from the intransigently proclaimed oil policies that gave his political base. In short retrospect, it was clear that he wanted to use foreign talks to help gain what today might be deemed as not unusual. This included international acceptance of the oil takeover without significant compensation, and freedom of oil production and distribution, perhaps with other oil companies. Proposals were bruited, there were exchanges between Tehran, London, and Washington, but the gap remained. Mosadeq had even gone to Washington and to the United Nations in New York to press his case, and his colorful presence provided reams of press copy.

If it could mean a settlement that would get the oil flowing, the United States decided it would be willing, both for its Cold War concerns and for non-disruption of the gulf oil industry and states, to exempt American companies in the national interest from antitrust laws so they might participate with others in the Iranian oil industry. The new Republican administration of 1953 followed the same course. There was still no solution.

Despite his theatrics that the West would be to blame and suffer if Iran’s disorganization proved a communist field day, Mosadeq had the ego and hubris to believe that he could control the two parts of his situation—the oil issue and domestic politics. He seemed to think that, over time, American intercession with the economically troubled British would become pressure the British could not resist, thereby bringing success without appreciable concessions to the British. Domestically he felt no worrisome challenge from the shah. The congeries represented by the National Front he expected to manipulate.

Pushing a good thing too far or losing proportion are not unknown in Iran, as elsewhere. With his power, Mosadeq had sycophants and politically motivated groups, such as the foreign minister and Tudeh sympathizers, who encouraged him to press. Of the two parts of his situation, America was not on Mosadeq’s wavelength.

The United States and the Iranian Problem

The United States, sympathetic to its ally’s financial problems and aware of the effects upon other oil operations in the Persian Gulf area, was not going to push for a debilitating, no-accommodation deal. It wanted a compromise. In regarding the Iranian flux it could see signs of strain in the National Front and restiveness among the shah and non-Front elements.

The United States was well informed. It had more than the Tehran embassy components and the three consulates at Isfahan, Meshed and Tabriz. There were two other large operations scattered in the country responsible to the ambassador: the Military Mission and the Point Four Technical Assistance Mission. The former worked, of course, with the military and was most careful to keep that work purely professional, while the latter was the biggest such program in the world, again very prudent in confining itself to agricultural, health, education and like technical help activities, with coordinating suboffices in major areas of the country. The leadership of both missions was excellent.

The shifting situation and operations generated regular requested and voluntary factual and analytical reports to Washington on varied subjects. And in Tehran close liaison among the American elements included joint conferences and evaluations, each element from its respective sphere. With a new team handling affairs in London and the British embassy, eventually by 1952 the American and British governments were getting joint assessments from their Tehran embassies. However, prolongation of the oil crisis finally provoked Mosadeq into breaking relations with Great Britain, and one late autumn dawn its diplomats left by car convoy bound for Baghdad.

As the crisis deepened from 1952 and into 1953, Iranian antipathies and suspicions were fanned against Americans. At the least it was not discouraged by the leadership, by some encouraged, and the Tudeh party (progressively active) and the large Soviet embassy aided its rise. The United States was literally the man in the middle. Since the Iranians were not realizing their oil hopes through America, since it was Britain’s NATO ally, and since domestic tensions were growing, the visible Americans became the target. It varied in parts of the country, but there were hostile incidents and demonstrations with something of a synthetic, organized character about them. Americans became cautious going about in public, while shouts, graffiti and doorway stickers had the same message, “Yankee, go home.”