Technology and Diplomacy: From the FSJ Archive

The following are selected excerpts from FSJ coverage of information and communications technology over the years.

Automation and the Foreign Service

The technology of automation will profoundly influence the work of the Foreign Service in the 1970s. The key elements of this change will be: 1) fast, cheap, direct satellite communications; 2) large computer data banks in Washington, and in a few regional posts abroad; 3) simplified and low maintenance computer terminals and classified long-distance Xerox facilities or similar equipment linking the department with most posts.

The principal challenge posed by automation in the 1970s is not technical. The real problem is our ability to anticipate and exploit the potential opportunities offered by automation. Inevitably, we shall have to examine our personnel needs, our way of doing business, and our customary approaches to problems. The challenge is a worthy one.

—From “Automation and the Foreign Service,”

by FSO Thomas M. Tracy, in the March 1971 Foreign Service Journal.

The Computer Generation

Since those innocent days of sailing ship communication, the business of diplomacy can be divided into several eras, all defined by technology: the advent of radio, telegraph and telephone, which linked overseas missions to Washington; the invention of the jet engine, which made it easier for leaders and diplomats to conduct face-to-face negotiations; and the simultaneous arrival of communications satellites and computers, binding the entire worldwide diplomatic apparatus into a real-time web that is as accessible as the screen of the nearest personal computer.

Of those changes, the last—now in its early bloom—may have the most profound impact on the management of foreign policy and the shape of the Foreign Service.

There are already signs that the classic management system of the State Department and embassies has begun to flatten and widen, bringing in more people earlier in the policy-making process. This represents a seismic change in the most traditionbound of the government services.

Under the new thinking, the embassy’s primary purpose would be to create a platform, supporting the work of all the agencies involved in foreign affairs. A chief of mission’s success would be judged on how well the interlocking team worked.

Technically, more will be possible in the future. The unresolved issue is how the real world of managing national security policy can be adapted to deal with the cyber revolution, and how to prevent the traditional hierarchy from being transformed into a computerized kind of anarchy that would badly serve the nation and its embassy personnel.

—From “Chugging Up the Onramp of the Info Interstate,”

by Jim Anderson, in the March 1995 Foreign Service Journal.

Bringing Foreign Affairs to the Home PC

Internet had helped bring international affairs to Main Street. For the average American with a home computer, foreign affairs is no longer only for academia and Washington bureaucrats. By using PCs to retrieve U.S. foreign policy documents from government agencies and to chat on the hundreds of international affairs bulletin boards, Net surfers are making foreign policy more a part of daily life for the average American than ever before in U.S. history.

—From “In Navigating the Internet, All Roads Lead to D.C.,”

by Dan Kubiske, in the March 1995 Foreign Service Journal.

National Authority in the Digital Age

I do not believe that the digital revolution heralds the end of the nation-state. It will, however, compromise the ability of a state to exert its domestic authority through jurisdiction over its geographic territory. It will also change the state’s role in the international political economic system: Technology will empower civil society advocacy groups to become significant actors in international politics.

A caveat is important here: The digital age is brand-new. We are witnesses to its birth and understand very little about what is happening, much less what will happen in the future. At this point prediction is difficult, if not impossible. What we can do is to imagine possible futures and think systematically about how they might affect us.

The Internet simultaneously provides the potential for both democracy and demagoguery, and it is too early to make a call about its impact.

I suspect that international negotiations and representation will be more rather than less important in the future, as governance of the Internet and the world economy becomes increasingly global.

—From “Will States Be Overthrown in the Digital Revolution?,”

by Stephen J. Kobrin, in the November 2001 Foreign Service Journal.

Welcome to the FS Blogosphere!

At the September 2007 launch of the State Department’s first Web log, Dipnote, Spokesman Sean McCormack welcomed readers to the site. Inviting them to be “active participants in a community focused on some of the great issues of our world today,” McCormack stated that the purpose of the blog was to “start a dialogue with the public” and to bring readers “closer to the personalities of the department.”

But in launching Dipnote, the department was not so much breaking new ground in foreign affairs as playing catch-up. Blogging is already well established among members of the Foreign Service. There are currently more than 60 frequently updated, unofficial blogs written by active and retired FS personnel and their family members.

The FS blogosphere reflects a profound generational shift in the way diplomats see themselves and their work.

—From “Welcome to the FS Blogosphere,”

by Marc Nielsen, in the March 2008 Foreign Service Journal.

Cloud Computing and the Development Gap

A new development in the information technology industry offers the possibility of accelerating social and economic development, even in this time of limited resources. Cloud computing, as it’s called, involved tapping into computing power over the Internet. This creates enormous economies of scale, substantially lowering the cost and eliminating the technical complexities and the long deployment cycles of planning, installing, maintaining and upgrading IT systems.

Although ubiquitous, affordable Internet access—or even reliable electricity—is not yet a reality, there are many pockets of the developing world that are equipped to take advantage of this new approach to delivering and consuming information technology.

—From “Using Cloud Computing to Close the Development Gap,”

by Kenneth I. Juster, in the September 2009 Foreign Service Journal.

Social Media and Public Diplomacy

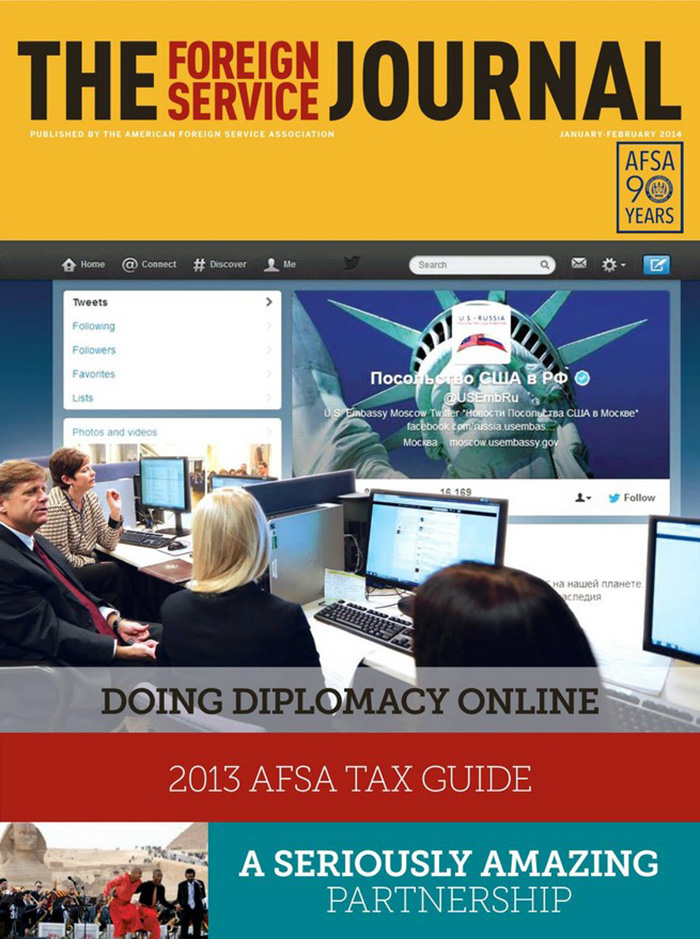

In recent years, Twitter and other social media have emerged as a lightning-fast, pointed alternative to traditional tactics of public diplomacy. Supplementing their usual portfolios, U.S. diplomats are being encouraged by the State Department to use both local and global social media tools.

The “social diplomacy” approach has proven to be especially important in countries like Russia, where government control of most broadcast media often distorts the message from Washington and news coverage about U.S. events and policies.

—From “Using ‘Social Diplomacy’ to Reach Russians,”

by FSO Robert Koenig, in the January-February 2014 Foreign Service Journal.

Diplomatic Reporting: Adapting to the Information Age

Critics have asserted that while U.S. diplomatic reporting has a rich and noble tradition in our country, it has suffered from the advent of the Internet and easy access to valuable open-source information. Embassy political and economic officers, who generally rejected this line, could now be directed to reduce their substantive reporting activities and take on more of the embassy’s operational duties such as managing congressional delegations.

Experienced FSOs and government analysts in Washington were quick to recognize, however, that while the Internet would narrow the diplomat’s reporting domain, it could not compete with the Foreign Service’s ability to provide policy-relevant insight and invaluable context with regard to local people, events and trends. In fact, bountiful online access to open-source information has the potential to make good diplomatic reporting even better.

—From “Diplomatic Reporting: Adapting to the Information Age,”

by John C. Gannon, in the July-August 2014 Foreign Service Journal.

Social Media for Reporting Officers

Think of these platforms [Twitter and Facebook] as the world’s largest cocktail parties, where everyone is invited and guests kindle conversations and relationships, just as in real life.

This [is] why, as a reporting officer, I consider my Twitter account essential to doing my job. We’re paid to get to know people, to build relationships with the influencers and information gatherers who can help us become better informed. Almost universally, these people are out in force on social media.

—From “Twitter Is a Cocktail Party, Not a Press Conference (or, Social Media for Reporting Officers),”

a Speaking Out column by FSO Wren Elhai, in the December 2014 Foreign Service Journal.