War Comes to Warsaw: September 1939

A riveting look back at the German invasion of Poland 80 years ago that ignited World War II.

BY RAY WALSER

Staff members drape a large American flag over the roof of the embassy in Warsaw in anticipation of German air attacks.

U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum / Julien Bryan Archive

U.S. Consulate General Warsaw on Sept. 1, 1939.

U.S. Library of Congress

Warsaw, Sept. 1, 1939, 5:30 a.m. The shriek of air raid sirens awakens Ambassador Anthony “Tony” J. Drexel Biddle Jr. Troubled by heightened German-Polish tensions, Adolf Hitler’s demands for territorial rectifications and the recent mobilization of the Polish Army, Biddle calls the duty officer at the Polish Foreign Ministry.

Is this an attack? The answer: Yes, there are numerous reports of German incursions onto Polish soil. Electing to telephone rather than cable flash news, Biddle manages to reach Ambassador William C. Bullitt in Paris. Bullitt, in turn, places a trans-Atlantic call.

2:55 a.m., Washington time. A sleeping President Franklin Roosevelt awakens to Bullitt’s call. After weeks of tension, a war of nerves is now a shooting war. The president alerts Secretary of State Cordell Hull and other senior officials. In the pre-dawn hours, lights suddenly begin to burn at the State Department. Twenty years after the peace settlement of Versailles, Europe again plunges into general war.

The German attack does not catch Ambassador Biddle or the department entirely by surprise. In March 1939 the department had outlined what today would be called an emergency action plan, granting chiefs of mission considerable authority to respond to imminent crises and mapping out numerous contingencies. Guidelines were issued for handling welfare and whereabouts cases, repatriations, protection of American property and representation of the interests of warring nations.

Following these instructions, Ambassador Biddle had requested permission on Aug. 21 to evacuate children, wives and other nonessential personnel. Soon afterward, American citizens were warned of an increased danger of hostilities and an evacuation route was arranged into what is present-day Belarus.

As another precaution, several American staff members moved to a safer suburban location outside Warsaw. Closing the mission, however, was considered a last resort. The department believed it was important to keep a diplomatic presence because the “continuing character of the office may avoid any question of ‘reopening’ or ‘establishing’ a consular office in territory under German control.”

In the hope of preventing a war, Great Britain and France dispatched their diplomats to Moscow in an effort to enlist Stalin’s support in curbing Nazi aggression. The Nazi-Soviet Non- Aggression Pact of August 23 aligning Hitler and Stalin—an act (albeit temporary) of geopolitical reconciliation between arch ideological enemies—had stunned the world. Hitler’s bold diplomacy now made war virtually inevitable.

A political appointee, Ambassador Biddle would be the man of the moment. Descended from a historic Philadelphia family, he served in World War I and was known in the 1920s and early 1930s as an extremely well-dressed “sportsman-socialite” on his second marriage to an heiress.

After backing Franklin Delano Roosevelt in the 1932 election, he had been named minister to Norway. He took to his new métier with enthusiasm, establishing close ties with Norwegian royalty. In 1937 FDR selected Biddle as the next ambassador to Poland. Immune to panic, throughout the September crisis, Biddle would demonstrate a readiness for action, a will to serve and enormous sangfroid.

While neutral in the conflict, the United States refuses to reward aggressors with the imprimatur of international legitimacy.

On Sept. 3, the third day of the Nazi invasion, Biddle wakes to the drone of low-flying aircraft. Taking shelter in a stairwell of his suburban villa, he and his family endure a German attack that sends shrapnel flying, shatters glass and deposits an unexploded incendiary bomb in his yard. The Biddles are among the first Americans to experience the fearful impact of modern aerial warfare.

That day, Great Britain and France, honoring commitments to stand with Poland, declare war on Nazi Germany. World War II officially begins. Sadly, neither Great Britain nor France will offer any significant assistance to the beleaguered Poles in the weeks ahead.

Fearing entrapment, as its gallant but weaker forces are being swiftly overwhelmed by the Nazi onslaught, the Polish government leaves Warsaw on Sept. 5. The Biddles, their Great Dane and several embassy staff, including five women clerks, follow at the Poles’ request.

Among those joining the ambassador is Eugenia McQuatters, one of several unsung and often overlooked female secretaries and code clerks who constitute an important cadre of State Department staff. To her surprise, Ms. McQuatters finds herself behind the wheel of a station wagon loaded with four female clerks, a Polish male and drums of gasoline, navigating unfamiliar roads in dangerous blackout conditions.

A brief stop along the escape route nearly proves fatal as German bombs hit the center of the market town, striking quite close to the temporary embassy. Fortunately, on Sept. 14, Biddle and his party safely cross into Romania.

To protect the embassy from German bomb blasts, sandbags cover basement windows.

U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum / Julien Bryan Archive

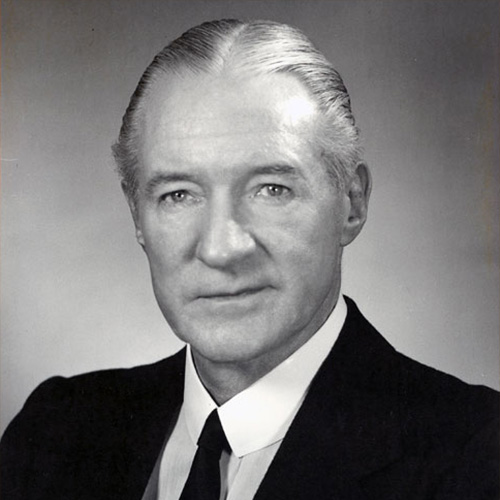

Anthony J. Drexel Biddle Jr.

U.S. Department of State / U.S. Embassy Oslo

With the ambassador’s departure, Consul General John Ker Davis assumes charge. He is a veteran consular officer with 20 years of experience, a China hand and a future president of the American Foreign Service Association. In Warsaw, with no safe escape route available, Davis adopts a shelter-in-place policy. In his after-action report, Davis recalls saying that “any officers who wished to leave were at liberty to do so, but in my opinion their chances of surviving would be greater were they to remain in the chancery.”

There are no new departures. Remaining American personnel move to the embassy, a location deemed more secure. It is a fortunate decision as German shellfire subsequently wrecks the consulate general. At the embassy, efforts are made to improvise a safe shelter with sandbags and extra timber supports to shore up the basement roof.

While bombs fall and artillery shells rain down, 40-year-old Julien Bryan, a fearless American photographer, captures for posterity vivid images of Poland’s agony, of the human and material devastation resulting from the brutal Nazi air and ground assault, including clear evidence of the terror attacks on purely civilian targets and the wanton destruction of Warsaw. Among Bryan’s films and photographs are enduring images of the American staff calmly observing an air raid and preparing to ride out the Nazi assault with improvised bunkers, protective sandbags and American flags on the roof.

Elsewhere, Bryan’s compelling photographs confirm reports sent by Ambassador Biddle and CG Davis regarding “unrestricted German attacks—by bombing and machine-gunning from airplanes.” Blitzkrieg is synonymous with merciless, indiscriminate air attacks against all.

CG Davis organizes the staff to perform a variety of duties from searching for food, performing housekeeping duties, standing watch and attending to the needs of approximately 80 refugees, many women, sheltering in the embassy. Lifting morale, urging forbearance and countering negative thoughts are priorities. Tensions mount among a staff reduced to sleeping on blankets on a cement floor. “An effort,” Davis later writes, “was made to discourage officers from dwelling on the possibility of their being killed.”

There are, according to CG Davis, frequent near-misses for embassy members who venture out into the streets in search of food or to gather information regarding the assault on Warsaw. All communications with the outside world are also severed.

Yet when a newsman asks Vice Consul William M. Cramp how long he is prepared to stay, he responds, “Until 136 American citizens are able to leave Warsaw.” Like Davis, Cramp is familiar with tense situations. In May 1936 in Addis Ababa, he helped organize the armed defense of the legation that beat off a mob of marauders and earned him a citation for bravery.

Relief for the trapped Americans comes on Sept. 21. Davis and other neutrals succeed in negotiating a truce allowing diplomats, American citizens and others (about 1,200 in total) to leave the besieged city. Once into German lines, smiling, courteous Germans and news cameras greet the weary, hungry Americans—good propaganda for Berlin.

By the following afternoon, Davis and his party reach safety at Königsberg, East Prussia.

Immune to panic, throughout the September crisis, Ambassador Biddle would demonstrate a readiness for action, a will to serve and enormous sangfroid.

From Berlin, Chargé Alexander Kirk cables the good news to the department. “In spite of the terrific ordeal through which they have passed they are in excellent health. …I feel that any expression of admiration for the magnificent courage, tenacity and resourcefulness which they have displayed during the past weeks would be feeble and inadequate.”

Under threat of invasion from Hitler, the Romanians deny safe haven to the fleeing Polish government of President Ignacy Mościcki and Foreign Minister Józef Beck. The Poles are not permitted to conduct official business and are essentially neutralized and interned by the fearful Romanians.

Meanwhile, on Sept. 17, Russian troops move to occupy roughly the eastern third of Poland. Returning to Moscow in late September, Nazi Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop joins Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov to sign a new agreement arising from “the disintegration of the Polish state” and cynically promising “a safe foundation for lasting peace in Eastern Europe.” Proud, independent Poland is for the fourth time in its history partitioned by predator nations.

Electing to remain behind is 41-year-old Thaddeus Henry Chylinski—an American-born Polish American, veteran of the Polish army and a long-serving clerk, later vice consul in Warsaw—and a handful of American citizens.

As Warsaw falls to the Nazis, defiant Polish patriots in Paris pass national leadership to President Władysław Raczkiewicz and General Władysław Sikorski, who was serving as premier and war minister. The new government is immediately recognized by France and allowed to operate on French soil and organize Free Polish fighters.

Embassy Warsaw staff watch German planes fly overhead.

U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum / Julien Bryan Archive

This colorized photo shows Julien Bryan filming on top of paving stones meant to serve as a barricade against the advancing German army during the siege of Warsaw.

Wikimedia Commons

Describing Poland as a “victim of force used as an instrument of national policy,” Secretary Hull announces that the United States will continue to recognize Poland’s government in exile. He tersely adds, “Mere seizure of territory … does not extinguish the legal existence of a government.”

While neutral in the conflict, the United States refuses to reward aggressors with the imprimatur of international legitimacy. As a nation-state, crushed by totalitarians, Poland no longer exists. As a people, as a hope for the future, it continues to live in the spirits of its citizens and friends.

On Oct. 15, FSO George Haering and three vice consuls return to Warsaw on a special train provided by the occupying Germans. They grimly report on the destruction that includes Consulate General Warsaw and the ambassador’s residence, along with damage to 14,000 of the 17,000 structures in urban Warsaw.

Military and civilian casualties run into the tens of thousands. Nonetheless, when the consulate general reopens some weeks later, a little of what was lost is regained. In a field report to the State Department, FSO Landreth Harrison asserts: “People in all walks of life frankly stated that when the Americans came back, it meant to them that Poland was not entirely forgotten by the outside world.”

In late September 1939, Ambassador Biddle arrives in Paris to preserve diplomatic contacts with the new Polish government. He will follow it to its temporary home at Angers, in the south of France. After the fall of France in June 1940, Biddle will then move to London, where he will be accredited by FDR not only to the Polish exiles but to a total of eight displaced governments overrun by Nazi invaders.

Photographer Julien Bryan will successfully evade German censorship, removing his priceless collection to give Western audiences graphic, heartrending evidence of the war’s devastation and human toll. This important collection resides today with the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

During a yearlong stay in Nazi-occupied Warsaw and living for months across from Gestapo headquarters, Thaddeus Chylinski will meticulously record evidence of mounting Nazi atrocities and war crimes. A comprehensive report written from memory but inexplicably classified for decades, Poland under Nazi Rule 1939–1941 chronicles the Nazi terror campaign against the Poles of all classes and religions. The report will only see public light after the 1998 passage of the Nazi War Crimes Disclosure Act.

In 1939 Warsaw witnessed professional commitment and fortitude from America’s diplomatic and consular corps under extreme duress. From ambassadors to clerks, these individuals were ready to do the right thing, defend the nation’s interests and protect the citizens they faithfully served. As Consul General Davis reflected in his June 1940 journal entry: “Wars may come, and wars may go, but the American Foreign Service ‘carries on.’”