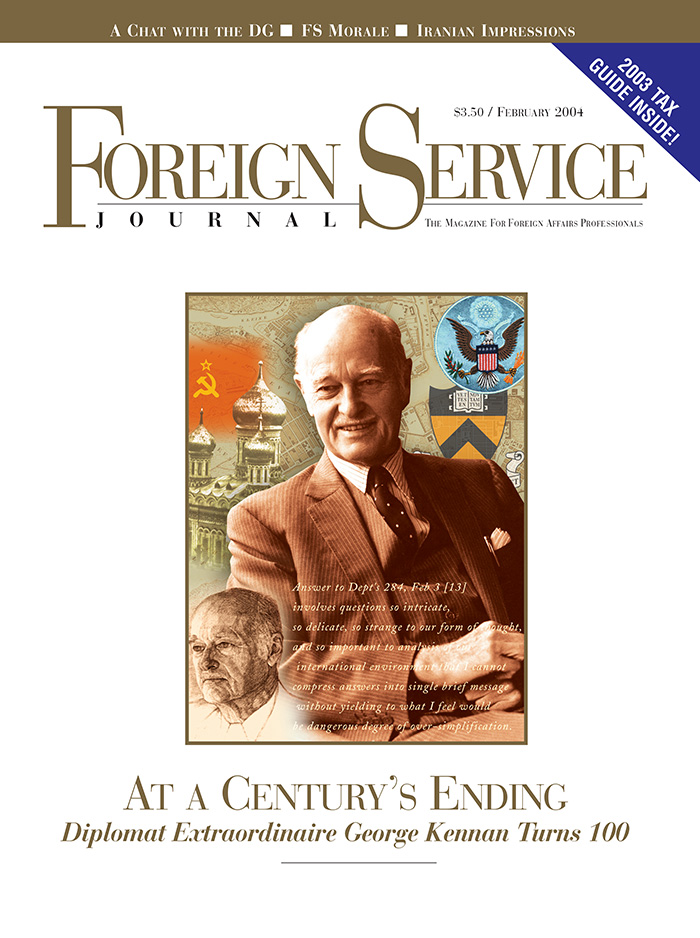

Measures Short of War

This presentation of diplomacy’s work in 1946, when the United States faced a new postwar world of great power competition, remains as relevant today as ever.

BY GEORGE F. KENNAN

This morning we consider the relations between sovereign governments and the measures that they employ when they deal with each other … short of reaching for their weapons and shooting it out. …The traditional lists of “measures short of war” (see chart below) were drawn up with the idea of the adjudication or the adjustment of disputes, and not primarily with the idea of exercising pressure on other states. …

The problems we are faced with today in the international arena are not problems just of the adjustment of disputes. They are problems caused by the conflict of interests between great centers of power and ideology in this world. They are problems of the measures short of war which great powers use to exert pressure on one another for the attainment of their ends. In that sense, they are questions of the measures at the disposal of states not for the adjustment of disputes, but for the promulgation of power.

These are two quite different purposes. Governments are absorbed today not with trying to settle disputes between themselves, but with getting something out of somebody else, so they often promulgate a policy which goes very, very far. Governments have to use pressure on a wide scale; and therefore these traditional categories are not often applicable to conditions today.

Now let’s go on to measures of pressure, as distinct from adjustment. The first thing that strikes me about measures of pressure is that they differ significantly in the case of totalitarian and democratic states. …Totalitarian governments have at their disposal every measure capable of influencing other governments as a whole, or their members, or their peoples behind their back; and in the choice and application of these measures they are restrained by no moral inhibitions, by no domestic public opinion to speak of, and not even by any serious considerations of consistency and intellectual dignity. Their choice is limited by only one thing, and that is their own estimate of the consequences to themselves.

The question then arises as to what measures the democratic states have at their disposal for resisting totalitarian pressure and the extent to which these measures can be successful. That is a tremendous question, not one on which I can give you a complete answer. I don’t have a complete answer. …

Measures at Our Disposal

Diplomatic Measures of Adjustment for the Redress of Grievances or for the Pacific Settlement of Disputes

AMICABLE

Non-Judicial

- Negotiations

- Good Offices, Mediation, and Conciliation

- International Commissions of Inquiry

Judicial

- Arbitration

- Adjudication

- Charter of the United Nations

NON-AMICABLE

- Severage of Diplomatic Relations

- Retortion and Retaliation

- Reprisals

- Embargo

- Non-Intercourse

- Pacific Blockade

The first category of measures lies in the psychological field. It would be a mistake to consider psychological measures as anything separate from the rest of diplomacy. They consist not only of direct informational activity like propaganda, or radio broadcast, or distribution of magazines. They consist also of the study and understanding of the psychological effects of anything which the modem state does in the war, both internal and external.

Democracies—ours especially—were pretty bad at psychological measures in the past, because so many of our diplomatic actions have been taken not in pursuance of any great overall policy, but hit-or-miss in response to pressures exercised on our government by individual pressure groups at home. Now those pressures usually had little to do with the interests of the United States. They weren’t bound together in any way. It is only recently and probably in consequence of the experiences of the last 8 or 10 years that our government has begun to appreciate the fact that everything it does of any importance at all has a psychological effect abroad as well as at home.

The second category of weapons short of war that we have at our disposal today is economic. Here, I’d like to give you a word of warning: it would be a mistake to overrate the usefulness of the economic weapons when they are used as a means of counterpressure against great totalitarian states, especially when those states are themselves economically powerful. This is particularly true of the Soviet Union, because the Soviet leaders consistently place politics ahead of economics on every occasion when there is a showdown. The Soviets would unhesitatingly resort to a policy of complete economic autarchy rather than compromise any of their political principles. I don’t mean they are totally unamenable to economic pressure. Economic pressure can have an important cumulative effect when exercised over a long period of time and in a wise way toward the totalitarian state. But I don’t think it can have any immediate, incisive, or spectacular results with a major totalitarian country such as Russia. …

On the strictly political measures short of war, I only mention one category because it, in my opinion, is our major political weapon short of war. That measure is the cultivation of solidarity with other like-minded nations on every given issue of our foreign policy. A couple of years ago, when we first had discussions with the Soviet authorities in Moscow about the possibility of setting up another United Nations Organization, I’ll admit that I was very skeptical. I was convinced the Russians were not ready to go into it in the same spirit we were. I was afraid the United Nations might become an excuse rather than a framework for American foreign policy. I was worried it might become a substitute for an absence of a policy. But I am bound to say, in the light of what has happened in the last year, I am very much impressed with the usefulness of the UN to us and to our principles in the world. There are advantages to be gained for us working through it. …

All the measures I have been discussing— economic, psychological and political— are not strictly diplomatic. Remember that diplomacy isn’t anything in a compartment by itself. The stuff of diplomacy is in the entire fabric of our foreign relations with other countries, and it embraces every phase of national power and every phase of national dealing. The only measures I can think of which are strictly diplomatic in character are those involving our representation in other countries. Those can be used for adjustment as well as pressure. …But you don’t have to break relations altogether. You can withdraw the chief of mission, reduce your representation, or resort completely to non-intercourse. You can forbid your people to have anything to do with the other country.

The measure which is most usually considered and used is the severance of diplomatic relations. The press often advises our Government to break relations with this government or that government. I am very, very leery of the breaking of diplomatic relations as a means of getting anywhere in international affairs. Severing relations is like playing the Ace of Spades in bridge. You can only use it once. When you play it, you haven’t got any more, so your hand is considerably weakened. …We ought to make plain to the world from now on that no American recognition—no American diplomatic relations with any regime—bears any thought of U.S. approval or disapproval; we are not committing ourselves, when we deal with anyone, on the legitimacy of their power. We would deal with the devil himself if he held enough of the earth’s surface to make it worthwhile for us to do so. …

A few other measures which democratic states can take involve control of territory in one’s own country, namely the facilities granted to a foreign government. We can limit the number of representatives of a foreign government in this country. We can deny its citizens the right to sojourn here for purposes of business or pleasure. We can deny them our collaboration in cultural or technical matters. They do these things to us all the time; and we can do them ourselves, although these measures are more difficult for us because our controls are not so complete.

These are, in general, the categories and measures I think we have at our disposal.

Two Main Conditions for Effectiveness

Now comes the real question. To what extent are these measures adequate to our purposes in the world today? Are they enough to get us what we want without going to war? My own belief is that they are, depending on two main conditions.

The first of these conditions is that we keep up at all times a preponderance of strength in the world. …It is not by any means a question of military strength alone. National strength is a question of political, economic, and moral strength. Above all it is a question of our internal strength; of the health and sanity of our own society. For that reason, none of us can afford to be indifferent to internal disharmony, dissension, intolerance, and the things that break up the moral and political structure of our society at home.

Another characteristic of strength is that it depends for its effectiveness not only on its existence, but on our readiness to use it at any time if we are pushed beyond certain limits. This does not mean we have to be trigger-happy. It does not mean there is any point in our going around blustering, threatening, waving clubs at people, and telling them if they don’t do this or that we are going to drop a bomb on them. Threatening in international affairs is about the most stupid and unnecessary thing I can think of. It is stupid because it very often disrupts the whole logic of our own diplomacy; brings in an element that didn’t need to be there; causes the other fellow to adopt an attitude which he needn’t adopt; and defeats your own purposes. …

Strength overshadows any other measure short of war that anybody can take. We can have the best intelligence, the most brilliant strategy, but if we speak from weakness, from indecision, and from the hope and prayer that the other fellow won’t force the issue, we just cannot expect to be successful.

This thought is a hard point to get across with many Americans. A lot of Americans have it firmly ingrained in their psychology that if you maintain your strength and keep it in the immediate background of your diplomatic action, you are courting further trouble and provoking hostilities. They insist it is the actual maintenance of armaments that leads to their use. Our pacifists are incapable of understanding that the maintenance of strength in the democratic nations is actually the most peaceful of all the measures we can take short of war, because the greater your strength, the less likely you are ever going to use it. They fail to understand that in the world we know today, the question is never whether you are going to take a stand; the question is when and where you are going to take that stand. …

What this boils down to, I am afraid, is that for great nations, as for individuals today, there is no real security and there is no alternative to living dangerously. And when people say, “My God, we might get into a war?” the only thing I know to say is, “Exactly so.” The price of peace has become the willingness to sacrifice it to a good cause and that is all there is to it.

A second condition must be met if our measures short of war are going to be effective: we must select measures and use them not hit-or-miss as the moment may seem to demand, but in accordance with a pattern of grand strategy no less concrete and no less consistent than that which governs our actions in war. It is my own conviction that we must go even further than that and must cease to have separate patterns of measures—one pattern for peace and one pattern for war. We must work out a general plan of what the United States wants in this world and pursue that plan with all the measures at our disposal, depending on what is indicated by the circumstances. …

My personal conviction is that if we keep up our strength, if we are ready to use it, and if we select the measures short of war with the necessary wisdom and coordination, then these measures short of war will be all the ones that we will ever have to use to secure the prosperous and safe future of the people of this country.