Partners in the Service: Foreign Service Wives a Century Ago

Foreign Service spouses have always played a critical role in U.S. diplomacy.

BY MOLLY M. WOOD

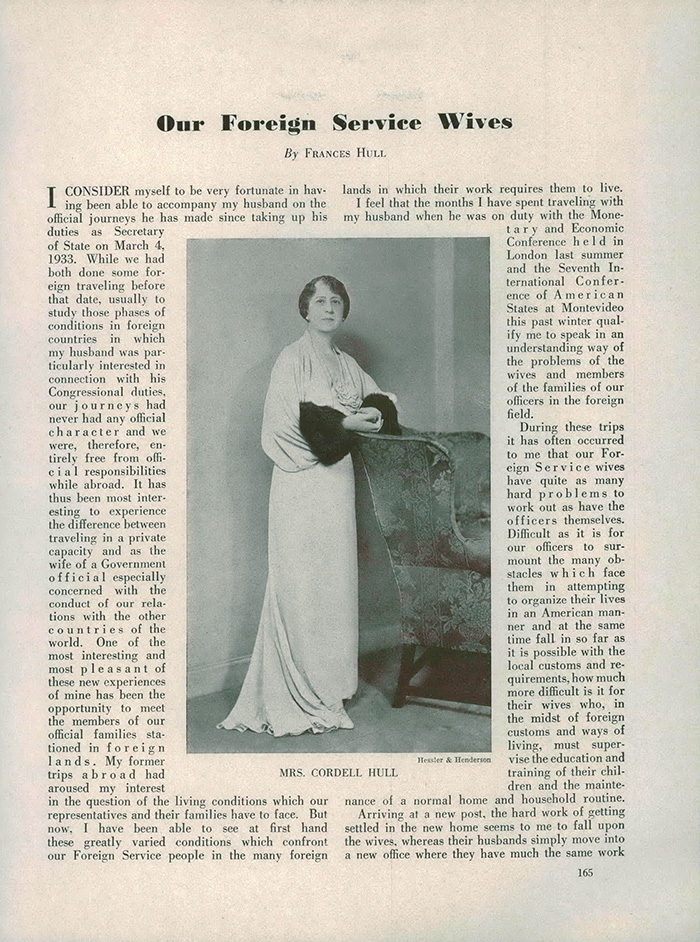

Secretary of State Cordell Hull’s wife, Frances, gave testimony to the vital role of Foreign Service spouses in the conduct of U.S. diplomacy in the April 1934 issue of The Foreign Service Journal.

The Foreign Service Journal

In 1905, Francis Huntington Wilson, “first secretary” at the American legation in Tokyo, was anxiously awaiting promotion and transfer to the State Department in Washington, D.C. Frustrated, Wilson “finally dispatched his beautiful and charming wife [Lucy Wilson] to Washington for a personal appeal to her friend, Secretary of War William Howard Taft.” Wilson hoped that Lucy Wilson could use her influence with Taft to put in a good word for her husband in Washington political circles.

Taft agreed to take Lucy Wilson to meet with the new Secretary of State, Elihu Root. A White House aide later reported that “when Root saw the Juno-like face of Mrs. Wilson and watched her sweep across the room … his eyes began to waver.” Root met Lucy Wilson alone in his office. Shortly afterward, he appointed Francis Huntington Wilson as “third assistant secretary” of State in Washington, D.C.

Lucy Wilson was not the only wife to successfully lobby for her diplomat husband in the early years of the 20th century. In 1911, Hallie Rives Wheeler, wife of an American diplomat posted to St. Petersburg, Russia, told President William Howard Taft “that she did not think her husband would live through another winter in St. Petersburg.” After Wheeler left the room, Taft remarked “that none of us statesmen were proof against a pretty woman,” and he directed Secretary of State Philander Knox to transfer the Wheelers to Rome.

A Terrific Burden

Diplomats themselves recognized the significant role their wives played in the U.S. Foreign Service. Career diplomat Earl Packer explained that “the wives carry a terrific burden” in the Service, while longtime diplomat Willard Beaulac declared: “I know of no field in which a wife can be more helpful.” At a time when the State Department considered “character,” “ability” and the capacity to “establish and maintain … a position befitting the commanding prestige of the United States among nations” as the “essential factors for success” in the Service, officials recognized that beautiful and charming Foreign Service wives could greatly enhance individual careers and American diplomatic representation abroad.

Foreign Service wives managed, without pay, the domestic duties and social obligations needed for the operation of American missions abroad. They also helped establish a powerful American presence overseas. Their visibility increased American prestige and reflected the very best of the “American way of life” to other cultures. The conduct of diplomacy, especially in the pre–World War II era, depended on developing and maintaining relationships with local officials and others in the diplomatic corps.

Foreign Service wives managed, without pay, the domestic duties and social obligations needed for the operation of American missions abroad.

Meeting and greeting. These political relationships, however, were also personal and social, an arena in which wives played significant roles. One wife recalled that her “entire life” in the Foreign Service in the 1930s “was to be devoted to being the best possible hostess.” A knowledgeable observer of the U.S. Foreign Service explained that “personal acquaintance with influential people in governmental and political life is often helpful in advancing the business of the legation.”

It was at the many social occasions that marked diplomatic life where representatives of the host country, other members of the diplomatic corps, and local dignitaries and visitors mixed, mingled and gossiped. Edith O’Shaughnessy, the wife of an American diplomat in Vienna in 1910 and 1911, remembered how she “cultivated” influential friendships.

Foreign Service officers relied on their wives to read and interpret both conversations and behavior in these settings, and then relay information back to them. Lucy Briggs explained that “a man who was perhaps not especially gifted was greatly helped by a wife who was friendly and who was interested in what was going on and who was helpful both in personal and professional ways.”

Social events provided numerous opportunities to curry favor, collect information and send subtle messages within the diplomatic corps. Hosting them served as a primary opportunity to exhibit American culture and prosperity abroad.

Who a wife invited, and did not invite, to her residence for tea might or might not be a reflection of government policies, but those invitation lists were always highly scrutinized. Officials at the State Department in Washington, D.C., expected wives to reach out to local women in the host country, and to work with them in local charities and volunteer groups.

Knowing the locals. Because those activities often took wives into different neighborhoods, beyond the borders of the official diplomatic corps’ offices and enclaves, they often knew the local environment, and the locals themselves, better than their husbands who were stuck in the embassy or legation all day.

As Elizabeth Cabot remembered, when she was in Rio de Janeiro, “I had to go to market. I had to move around [her emphasis]. … It made you link up with people.” Naomi Matthews explained that when she and her husband were in Australia in the 1930s, she “was with the Australians much of the time … that’s what you want to do. That’s what you are there for.”

Many wives keenly felt the pressure of the spotlight, which they often referred to as living in the “goldfish bowl” where “you’ve got to be so careful.”

Obeying rules now bygone. Wives also understood, as did their diplomat husbands, that the State Department was keeping a close eye on them, and that their conduct and behavior were included in the formal promotion assessments that became a regular part of the Foreign Service after 1924.

As Lucy Briggs remembered, “In those days, when a man’s record was written up, his wife was always commented on. And if she added to his social position in a pleasant way, or if she was helpful in other ways, that was always put down. Or if she was something of a handicap that was put down, too.”

After 1924 the members of the new Foreign Service Personnel Board discussed their expectations that wives would make a “host of friends” abroad and would “entertain with a kindly and likeable disposition.”

Setting up hearth and home. Wives were also primarily responsible for family logistics. When Foreign Service officers received transfer orders from the State Department, for instance, they often moved immediately to the new post to live temporarily in a hotel, leaving their wives behind in the previous post to make arrangements for the often arduous task, in this pre-flight era, of transporting all possessions, and often children, to reunite the family in the new location.

Yvonne Jordan remembered the difficulties she encountered when trying to move, with an infant son, from Haiti to Helsinki in 1922. In addition, she had to pay for her and the baby’s travel out of pocket after being informed by the State Department that “the travel expense fund was exhausted.”

The haphazard nature of overseas posting made it difficult, if not impossible, to plan ahead. After arriving in a new place, wives shouldered the primary responsibility for setting up the new household, whether it be the ambassador’s residence or a third secretary’s apartment.

The State Department during these years assumed no responsibility for housing its employees, yet still expected that American diplomats and their families be “well housed” to display American power and prestige. Their homes, the daughter of FSO Edwin Kemp and his wife, Anna, remembered, were supposed to embody “American tastes and customs.” A wife who “maintains an attractive home,” she continued, could be “a very real asset to her husband in his task of representing the U.S.”

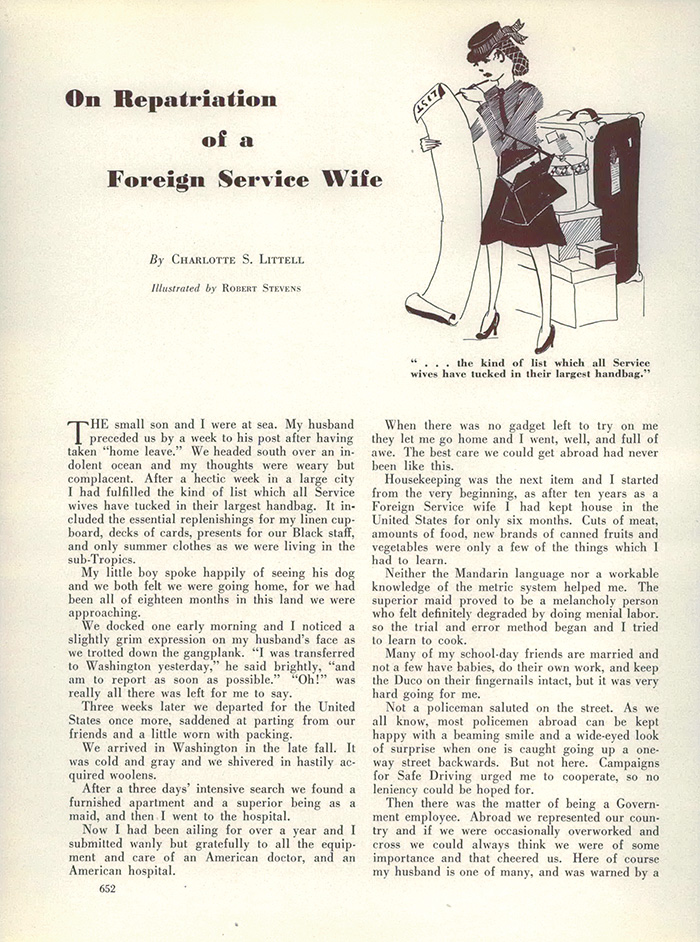

Charlotte S. Littell, a Foreign Service wife, tells the story of getting to post a month behind her husband only to find he has been reassigned back to Washington, D.C. In the December 1939 FSJ, she describes the ordeal of relocating, including the many challenges of going “home.”

The Foreign Service Journal

Dressing for success. Wives were also acutely aware of the importance of their outward appearance at all times when in public. Dressing correctly for the occasion demonstrated adherence to diplomatic protocol. Looking good and fashionable also communicated positive messages about American material prosperity and level of civilization.

Dorothy Emmerson, for example, claimed to know nothing about the Foreign Service when she married John Emmerson in 1934. She was given explicit instructions to “wear a long dress—with train—long sleeves, high neck, hat, gloves, no white, no black” when she was to be presented to the Imperial Family of Japan in 1935. By complying with these instructions, she communicated a message of conformity, goodwill and an understanding of diplomatic protocol.

Many wives keenly felt the pressure of the spotlight, which they often referred to as living in the “goldfish bowl” where “you’ve got to be so careful” to dress correctly, to do the right thing, to not offend anyone. As Elsie Lyon added, the wives also had to avoid “close ties with people in the Embassy or you’re playing favorites.”

Managing family life. Yet there was a real camaraderie inside the American diplomatic corps. Wives regularly referred to the pre–World War II Foreign Service as “one big family” where “you sort of knew everybody.”

Elsie Lyon understood better than most the importance of family in the Foreign Service. She and her sisters grew up in a Foreign Service family headed by Joseph and Alice Grew. All the Grew daughters married Foreign Service officers. Lyon’s sister Lilla Grew Moffat later remarked that growing up in the Service gave them excellent training in “the responsibilities and obligations and duties” of the Foreign Service.

Wives at that time described themselves not as “helpmates” to their husbands, but as associates or partners who “joined” rather than “married into” the U.S. Foreign Service.

The Grew family and others recognized that child-rearing and family life represented another significant part of diplomatic life, even though many Foreign Service wives had little time to care for their children, and usually relied on a nanny or other domestic help. As Yvonne Jordan stated simply, “It was difficult to care for a child” while juggling all her other responsibilities.

Most diplomatic families at this time depended on domestic help, often from locals. Supervising servants fell to the wives. Wives complained that they had to train their servants to perform the duties needed by a diplomatic household, a challenge often compounded by cultural and language barriers. Dorothy Emmerson considered that supervising servants was often “in itself a full-time job” and that this particular obligation was “the most difficult part of the Foreign Service.”

Managing a large staff in a foreign environment was complex, especially given cultural mores, such as the caste system in India, that were unknown in the United States. In their interactions with servants, wives were thrust into a formal position of authority while living in a foreign culture they often did not understand.

They also did not receive any formal language training (and neither did most Foreign Service officers, with a few exceptions). Many took the initiative to learn a language once they arrived at a new post. Some already had skills in such areas as French or Spanish; others were less adept. Could Barbara Kemp really be expected to learn “Rumanian”? Yvonne Jordan struggled with Finnish before giving up and declaring it to be a “fiendish language.”

A Real Career

Foreign Service wives in the early 20th century perceived their quasi-official roles in the Foreign Service as positions of considerable importance and authority. Their work gave them status and visibility, which often blurred the distinction between private citizen and government employee. They were rightfully proud of the multiple important responsibilities they had in their husbands’ careers and in implementing U.S. foreign policy. They considered that their work for the State Department, even though unpaid, constituted a real career.

Dorothy Emmerson, who started in the Service in the 1930s, expressed frustration whenever someone asked her if she regretted not pursuing a career of her own—she identified her position as the wife of a diplomat to be her career. Naomi Matthews appreciated the fact that her husband “always said ‘we’” when he referred to their work and life in the Foreign Service.

Wives at that time described themselves not as “helpmates” to their husbands, but as associates or partners who “joined” rather than “married into” the U.S. Foreign Service. They understood that American diplomatic practice depended on them for a variety of formal and informal duties. Their individual stories have remained mostly untold and have yet to receive the widespread recognition they deserve.

Sources and Resources for Women in the Foreign Service

Sources for this essay include a variety of published histories of the U.S. Foreign Service and published memoirs. The piece also relies on archival research in the Foreign Service Personnel Boards State Department records at the National Archives in College Park, Maryland, and on interview transcripts of former Foreign Service officials and their wives, which are located in Special Collections at Georgetown University’s Lauinger Library in Washington, D.C. I am grateful to both archives for permission to quote from these collections.

The interview transcripts from Georgetown University have now been added to the extensive and ongoing Foreign Service Oral History Project directed by the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training. The transcripts are accessible through the ADST website: www.adst.org.

Another rich, new primary source for material on women in the Foreign Service is the FSJ Digital Archive, containing 100 years of diplomatic history in the pages of the American Foreign Service Association’s monthly Foreign Service Journal. For a curated selection of articles on women in the Foreign Service, please see “Women in Diplomacy” and “Foreign Service Families” on the FSJ Archive’s Special Collections webpage (afsa.org/fsj-special-collections).

—M.M.W.

Read More...

- “Making it Work: Conversations with Female Ambassadors” by Leslie Bassett, FSJ, July-August 2017

- “Our Foreign Service Wives,” by Frances Hull, FSJ, April 1934

- “Resolution of the Wives’ Dilemma,” by Carroll Russell Sherer October 1973