Engaging Our Host Country’s History

Reflections

BY LAURA M. FABRYCKY

Bonhoeffer-Haus in Berlin, Germany, 2008.

Axel Mauruszat / Wikimedia Commons

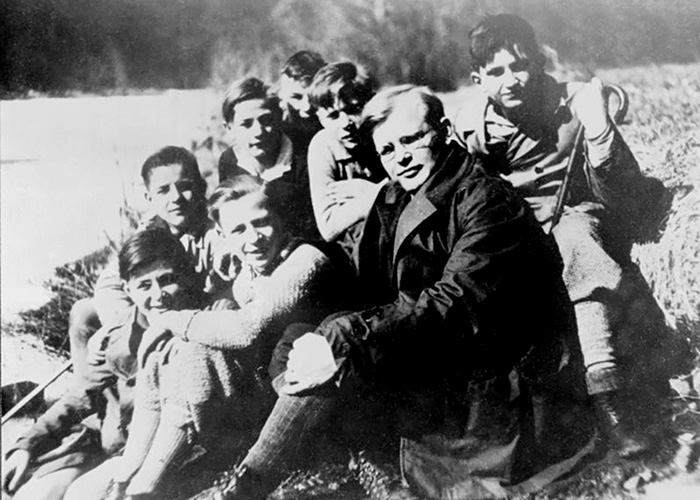

Dietrich Bonhoeffer with students in the spring of 1932.

German Federal Archives / Wikimedia Commons

In recent years, after multiple Foreign Service assignments, I have come to recognize how rarely I saw the histories of our host countries as stories on their own terms, especially ones I could learn from as an American, and not merely as local curiosities or intellectual entertainments.

Berlin opened my eyes. It is full of captivating stories, some closely entwined with our own. In fact, since World War II, some of the greatest expressions of American rhetoric, from President John F. Kennedy’s famous “Ich bin ein Berliner” speech to President Ronald Reagan’s “Tear Down This Wall,” belong to this great city.

Our family lived on Berlin’s southwest side from 2016 to 2019, and our children attended the specially chartered binational and bilingual John F. Kennedy School. As we settled into our new home in the fall of 2016, however, I was feeling strangely alienated from our home back in the States because of the partisanship that was cleaving our nation.

My hope was renewed by a very local story, one about the World War II–era German pastor Dietrich Bonhoeffer (1916-1945). Learning about Bonhoeffer’s life, how he assessed what it meant to be German and what that responsibility meant for him, would prove to be a unique source of nourishment for my civic imagination.

During our first year in Berlin, I visited his former family home—the Bonhoeffer-Haus—many times. Each visit offered new angles of discovery and meaning, especially during the final reflective pause in the top-floor bedroom where the Gestapo arrested Bonhoeffer in 1943.

Since 1987, when it was officially memorialized, the Bonhoeffer-Haus has been a place for visitors to learn about his life and think responsibly about their own. Though I had read a few of Bonhoeffer’s devotional writings and a biography, it was not until I saw this house and culture in situ, and listened to Germans interpret his local legacy, that I began to truly relate to Bonhoeffer’s story, and what I could learn from it.

Eventually, I asked if I could volunteer there as a guide. To my amazement, I was welcomed and issued a key. It hung on my keychain alongside my U.S. government–issued house and official post office keys, tokens of my responsibilities to particular places and their stories.

For the remaining two years of our Berlin tour, I walked more intentionally in the pages of another people’s history, guiding English-speaking visitors from all over the world through Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s incredibly brief, light-filled life.

Learning to tell his German story—amid the tumult of the first half of the 20th century—required that I pay better attention to my own American habits of heart and mind, and to how I narrated our nation’s civic stories.

For one, my German colleagues at Bonhoeffer-Haus told a more communal story of Dietrich Bonhoeffer than I knew, depicting him less as a singular hero (as we Americans prefer our heroic tales) but rather as a man who was marked by his belonging to others.

By all accounts, his destiny as the sixth of eight children born to Dr. Karl and Paula Bonhoeffer, a well-to-do family in Berlin’s Grunewald neighborhood, should have been secure and comfortable, with a future full of bright accomplishments.

Laura Fabrycky at Bonhoeffer’s desk during her first visit in November 2016.

Courtesy of Laura Fabrycky

Laura Fabrycky gives a tour of the Bonhoeffer-Haus in Berlin in 2019.

Courtesy of Laura Fabrycky

Like his parents and siblings, he was intellectually and emotionally gifted, skilled in the arts of friendship, music, scholarship, teaching and community-building. Each of these skills he first learned at home, in a loving, large and relatively happy family that treasured humanism and conviviality, and honored obligations to others.

Their lives were engulfed not once but twice by war, and by the many civic and political troubles that shook Germany during the first half of the 20th century. Like so many of that generation, his life was swallowed up and eventually ended by the specter of National Socialism.

Bonhoeffer realized early on that Nazi ideology posed a profound danger to Germany. He disagreed robustly and publicly with many of his fellow Christians who enthusiastically embraced the party and its ideology.

In a radio address in early February 1933, Bonhoeffer even warned against a Führer (leader) who becomes a Verführer (misleader), never naming Hitler but describing the social dynamics of his rule with unmistakable clarity. Bonhoeffer spoke, wrote and organized against Nazi influence in the German church.

In 1939, friends in the United States offered him a teaching position at a seminary in New York—an honorable plan of escape from Germany and its wartime demands. Initially, Bonhoeffer accepted, but after only a few weeks in the United States, he returned to Germany to embrace his responsibilities to his country and its struggle for a hopeful future.

After several years in German military intelligence (Abwehr), where he worked as a double-agent helping to smuggle Jews out of Germany and build links with the outside world for the German resistance, Bonhoeffer was arrested by the Gestapo at his family home in April 1943, on a minor and unrelated charge.

When the Valkyrie plot by German generals and a group of civilian allies to overthrow Hitler failed in July 1944, Bonhoeffer’s small role in that larger operation was also eventually unearthed.

After two years of imprisonment, he was put to death on Hitler’s orders on April 9, 1945, in the Flossenbürg concentration camp, just weeks before Allied forces arrived to liberate it.

One of Bonhoeffer’s central lessons in life was his practice of asking questions, to himself and his family and friends. These are not German questions but human ones—true for all people, everywhere.

They are particularly challenging to individuals engaged in the nomadic Foreign Service life: To whom and to where do I belong? How have those people and places influenced me? What do I owe my fellow citizens? How am I connected, and in some ways obligated, to others, even to those with whom I have robust disagreements?

These questions about civic participation and belonging matter even when our citizenship is practiced far beyond our nation’s shores.

At the Bonhoeffer-Haus, I was always struck by how my German counterparts spoke openly about the guilt and shame of their history, and how important it is to grapple with history in order to better prepare for the future.

Learning about the man in the context of his home, I was reminded that the small, seemingly insignificant decisions we make day by day do, in fact, make up and influence history.

Like Bonhoeffer, we who belong to particular people and places are implicated in history, too, whether our names ever grace a history textbook or our house is ever memorialized for visitors. That most elemental truth about our American civic life still bears repeating, especially for those who will come after us.

I have since surrendered my key to Bonhoeffer-Haus, and our family has settled into our next posting, as those of us living this privileged Foreign Service life continue to do. We now live, work, learn and try to serve among new people and new places.

Here, in our new home outside Brussels, I have not stopped looking for the stories that this new place offers, especially as a way to inform and care for our own American stories.