A Song for Unsung Heroes: Getting #AmericansHome from Ecuador

Diplomats at U.S. Mission Ecuador drew on talent, creativity and sheer determination.

BY AMELIA SHAW

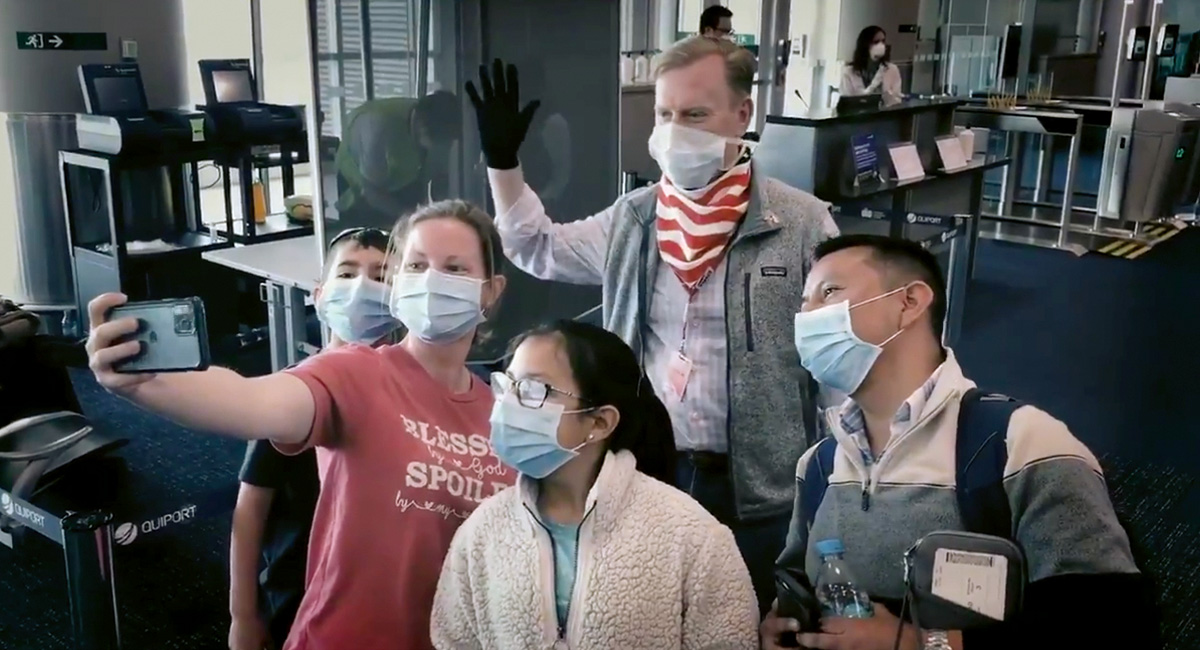

U.S. Consulate Guayaquil personnel assist American citizens at José Joaquin de Olmedo International Airport.

U.S. Mission Ecuador

U.S. Mission Ecuador

When the order came down on March 12 that the country would be going into lockdown, many in U.S. Mission Ecuador were still processing what that would mean. School closings. Curfews. A run on the local supermarkets. A medical system overwhelmed.

But for the consular teams in Quito and Guayaquil it simply meant—let’s get to work. And for Alex Delorey, Ecuador’s consular coordinator with 17 years of Foreign Service experience, this was a situation for which there is no preparation.

“We practice crisis response, for localized events. For an earthquake, or a volcanic eruption. But not this,” says Delorey. “We have never experienced a global pandemic where all other countries are equally impacted. So sometimes we had to make it up as we go.”

Mobilizing a Massive Operation

When Ecuador abruptly closed its borders on March 15, an estimated 8,000 Americans reached out to the embassy asking for help to get back to the States. It was up to the embassy and consulate to figure out who they were, where they were, and then get them out.

“It was a massive operation,” says second-tour FSO Scott Risner, who was manning the phones from his home in Quito and working with his colleagues in Guayaquil to figure out who needed help. “There are more than 100,000 American citizens living in Ecuador. We had to quickly collect data and build an information infrastructure to identify which people wanted to leave, and then get them accurate information.”

As of March 15, Ecuador, with a population of some 17 million, had confirmed 37 positive cases of COVID-19 and two deaths. But as elsewhere the virus spread rapidly, particularly in the coastal city of Guayaquil, whose first recorded case was traced to a traveler who returned from Spain. In a matter of days, Guayaquil would lead the nation with 70 percent of coronavirus cases.

For Americans wanting to leave Ecuador, what complicated matters was that, as in many countries, commercial airlines stopped flying. So mission staff had to figure out how many potential American passengers there were, then contact airlines and convince them there was enough demand to send an aircraft. Once a flight was confirmed, the mission shot out MASCOT [Message Alert System for Citizens Overseas Tool] messages to registrants of the Smart Traveler Enrollment Program (STEP) and social media posts urging Americans to book their tickets.

In short, it was pretty complicated.

As curfews tightened, travel by road became nearly impossible, causing an outcry from American citizens in cities across the country.

“We were working with airlines to charter planes, we organized humanitarian flights, we set up a processing center at the airport—and then realized that many Americans, while scared, were not necessarily ready to go home,” says Delorey.

As media coverage of the virus in the United States painted an increasingly grim picture at home, stranded Americans in Ecuador wrestled with what to do. To connect people with flights, consular and public affairs teams worked around the clock through social media and also set up a 24-hour phone line run by 40 staff in Guayaquil and Quito.

“The public affairs team even started posting information on a Facebook group, Americans Stranded in Ecuador, which had hundreds of followers,” says Risner. “There were so many rumors out there. We were fighting to give accurate information so people could have faith that these charter flights were even real.”

A Letter Unblocks a Road

As curfews tightened, travel by road became nearly impossible, causing an outcry from American citizens in cities across the country. Guayaquil’s Consular Chief Gabriel Kaypaghian recounted how creative thinking and teamwork helped get people through police barricades to reach international airports.

“People were calling us from Cuenca saying they had no way to get to the airport,” he said, “because taxi drivers were scared.” They didn’t want to make the four-hour drive and risk arrest for breaking curfew. So consular staff came up with the idea to procure a letter from the U.S. ambassador requesting Ecuadorian law enforcement to grant safe passage for American citizens to travel to the airport. It worked.

“The best ideas,” says Kaypaghian, “often come from the bottom up,” from officers working the issues on the front lines. “After a few days, we were able to work with mission teams in management, regional security and consular sections to organize buses from Cuenca and Manta to get people safely to the airport.”

Despite consular teams working around the clock, flights were intermittent, and it took weeks to get stranded Americans out.

An Airport Bon Voyage

Consular staff donned face masks and gloves and headed to the airport, helping with logistics and calming frayed nerves of American travelers. First-tour officer Amelia Hintzen remembers the exhaustion of spending a full day fielding congressional inquiries on American citizens, then heading to the airport that night to support passengers leaving on a 2 a.m. flight.

“It was chaos. People just needed so much help,” says Hintzen. She remembers lending people her cell phone to call their parents in the States, and translating information from airport personnel to scared Americans.

“I was exhausted, but then the adrenalin kicked in,” she says. “What hammered home for me was how important it was for people to see the U.S. embassy there.” Hintzen described how passengers were visibly relieved to see mission staff wearing cargo vests with the American flag on them: “It was like we made it all real to them, that they were really going home. Us just showing up and caring—it made people feel better.”

U.S. Ambassador Michael Fitzpatrick was also a common figure at Mariscal Sucre airport in Quito, wearing an American flag bandana around his neck like a cowboy, personally saying goodbye as Americans boarded the planes to go home. “It means a lot to me to go to the airport,” mused Fitzpatrick. “This is why we joined the Foreign Service—to serve the American people. Every single day.”

Pressure Mounts, Testing Strength

Despite consular teams working around the clock, flights were intermittent, and it took weeks to get stranded Americans out. Some lashed out on social media and others were quoted in international press saying they felt abandoned by their government.

“It was hard to work under all that media pressure,” says Kaypaghian. “Particularly in Guayaquil, which is the epicenter of coronavirus cases for Ecuador.” By late March, the city had captured world attention with grim images of corpses in the streets, and rumors of mass burial sites.

As the days ground on, consular managers became increasingly conscious of the need to take care of their staff.

U.S. Ambassador Michael Fitzpatrick, with his signature red-striped bandana, takes a selfie with a departing American family at Mariscal Sucre International Airport in Quito.

U.S. Mission Ecuador

As the days ground on, consular managers became increasingly conscious of the need to take care of their staff.

“Before State, I was a military man for 24 years,” says Quito Consular Chief Delorey. “And in the Army, the attitude is ‘just get it done.’ But that’s not the case here. You have to let people vent, let them express how hard this is, or even tell them to go home and take a break if they need it.”

For Delorey, Operation #AmericansHome was about resilience and creativity. It was also about drawing strength from the direct face-to-face with Americans in need. “My staff were magnificent. All of them wanted to be at the airport, they wanted to be helping—even if it meant exposure,” he says, commenting on the team’s commitment to service. At times he had to convince them to take downtime to rest, so they could face another taxing day.

For Kaypaghian in Guayaquil, strength came from teamwork. “What got us through was the creativity and talent of our officers to find solutions in what was an almost impossible situation,” he says of his staff. “And they did.”

Amelia Hintzen says she drew strength from colleagues around the world going through similar situations: “My friends serving in China who went to evacuate Americans from Wuhan, they were with me all the time, sending me tips on WhatsApp. That mutual support, I grew to rely on it.”

By the beginning of April, Mission Ecuador had repatriated thousands of Americans. The team remains in Ecuador, ready to help many more who have decided to hunker down and wait out the crisis. And like most members of the Foreign Service around the world, they are watching the news from home and trying to keep in touch with family members and loved ones, just hoping they will be okay.

“This is not just professional. It’s also personal,” says Ambassador Fitzpatrick. “We are all separated from our families,” he adds, commenting that his wife and daughter are in the United States. “Helping to reunite Americans with their loved ones in the States, this is our part. This is one thing we can do right now to help in this massive global crisis.”

Read More...

- “Helping Ecuador Respond to COVID-19,” U.S. Embassy Ecuador

- “Ecuador’s Death Toll During Outbreak Is Among the Worst in the World,” by José María León Cabrera and Anatoly Kurmanaev, NYT, April 23, 2020

- “COVID-19 Numbers Are Bad In Ecuador. The President Says The Real Story Is Even Worse,” NPR, April 20, 2020

- “Get Me Out of Here! American Diplomat Episode with Consular Officers Gabriel Kaypaghian and Ian Hayward,” American Diplomat, May 15, 2020

- “Amb. Mike Fitzpatrick Visits the Airport.” U.S. Embassy Ecuador, Facebook