Rescuing a Peace Corps Volunteer in Sarh

Reflections

BY PETER HARDING

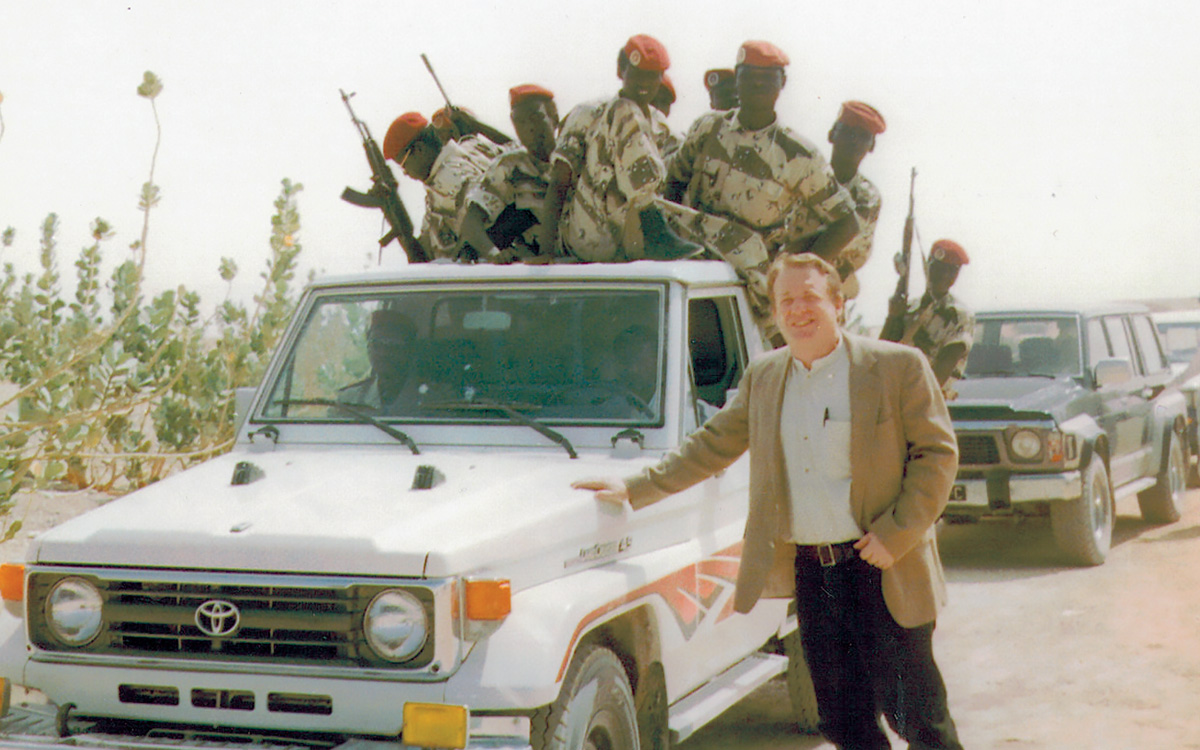

Peter Harding, the U.S. political-economic-commercial-consular officer in N’Djamena, during a political and economic reporting trip along the border with Nigeria in 1997—months after the incident recounted here. The Chadian government provided Harding with an armed escort because the area was (and still is) dangerous.

Courtesy of Peter Harding

Sometimes, it turns out that a diplomat has to choose between lying for his country to save a life and telling the straight and narrow truth, only to potentially suffer the consequences. The consular course at the Foreign Service Institute may hesitate to use an experience I had in Chad in 1997 as an example in the American Citizen Services’ “thinking on your feet” handbook, but I’d like to think there might be a hidden wink and an unspoken nudge in the hesitation.

I was stationed at Embassy N’Djamena from 1996 to 1998. The incident in question occurred almost precisely midway through my tour. Our embassy had a solid front office and country team, but was often gravely shorthanded. In my case, I had many hats to wear: I was the political officer, economic officer and commercial officer, as well as the sole consular officer. I had three separate offices in two different buildings and only one Foreign Service National assistant.

Always busy multitasking (as the saying now goes) but always coming up a day late and a dollar short, I would come in on the weekends to catch up and read correspondence. One Sunday near the end of my first year, there was a handwritten note on my desk from the ambassador that read: “I need to see you right away.”

I walked over to the residence, which was in the same compound as the chancery, to meet with him. As soon as I arrived, the ambassador said: “We have a ‘situation’ down south, which I need you to help resolve immediately. It seems that a Peace Corps volunteer was involved in some kind of accident and has been arrested. The PCV has apparently been charged with manslaughter, and the victim’s family is threatening to lynch him.”

I made some calls in my capacity as commercial officer and discovered the Esso-led oil consortium in country had a small Twin Otter aircraft that flew daily to the southern oil fields near Sarh, where the incident in question had occurred. Foolishly dressed in a grey pin-striped wool suit, I met up at the airstrip with the Peace Corps nurse, a Cameroonian named Dorothy, to fly down to Sarh, about 500 kilometers south of N’Djamena.

Dorothy and I were the only passengers on board. The pilot, a Pakistani from Rawalpindi, informed me that he could drop us off in Sarh around 11 a.m. and would be returning at about 2 p.m. He told us that if we weren’t at the airstrip at 2 o’clock sharp, he would take off directly for a return flight to N’Djamena regardless.

On arrival, we grabbed a local taxi and asked where the governor’s office was. “The governor is not here,” the driver replied. “A relative of his was recently killed in a bicycle accident, and he is out of town attending the funeral.” (Uh-oh!)

“So who is in charge?” I asked.

“The attorney general,” he said, cautioning that the man was notoriously corrupt.

When we arrived at the AG’s office, I asked for an immediate audience.

The meeting included the attorney general himself, his assistant, nurse Dorothy, me and the frightened-looking Peace Corps volunteer, who had been released from jail (at our insistence) with a bandage on his head.

The attorney general’s assistant then told us the story:

A village chief, a close relative of the governor, possibly drunk on palm wine, was coming down a hill on his bicycle. Riding up the hill was this young PCV wearing a helmet. Improbably, neither one saw the other, and they collided.

As fate would have it, the front tires of the bicycles perfectly touched each other, and both riders went over the handlebars and conked heads. The PCV survived because he was wearing a helmet, but the village chief died. The village chief left behind four wives and as many as 25 children.

The young man was formally charged with manslaughter. In addition, as is the custom in this part of Chad, his family and friends were demanding either revenge or compensation.

Once his assistant had finished, the AG promptly asked me, “So, which will it be?”

“Well, he’s an American citizen, so we intend on taking him back to N’Djamena as soon as possible for medical treatment.”

“You can do that under one condition: that you sign a piece of paper I’ve prepared, which will ensure financial support for the village chief’s wives and children as long as they live.”

“I’m afraid I don’t have the authority to do that, even as a consular officer.”

“Well, I strongly advise you to sign this piece of paper because if not, once the funeral is over, a large crowd will gather here, and we will be unable to prevent the lynching of this young man.”

I asked the AG if I could use his telephone to call the presidential palace. In those days, it took at least 20 minutes to place a long-distance call from Sarh to the capital. I was finally able to get hold of one of President Idriss Déby’s closest advisers, with whom I had a good working relationship.

I explained the situation and asked if he or the president could intercede on our behalf. He told me that the way they ran things in the capital was to not, repeat, not interfere in local affairs, and that there was nothing he could do to help me. Luckily enough, there were no speaker phones back then, and I was the only one who heard this.

Deciding to take advantage of that fact, I told the presidential adviser, in a voice that was probably louder than strictly necessary: “Hey, that’s great! Thank you very much. We’ll have him on the next plane headed north. I’m greatly indebted for your help on this. My best regards to the president.” I then hung up the phone.

The AG looked shocked. I grabbed the PCV’s hand and signaled to Dorothy to hurry down the stairs immediately and into the waiting taxicab. We beelined to the dirt airstrip. As I looked at the sky, I thanked God that the red Twin Otter was circling and ready to land. Still, it would be a close call.

Once the plane touched down and taxied to a stop, I ran up to the pilot and asked how long he planned to be on the ground. He said, “No more than 20 minutes to refuel.”

“How about two minutes?! And skip the refueling,” I said, pointing down the road to two army Toyota pickup-type trucks with soldiers clustered in the back. They were wearing red berets, carrying rifles and heading our way pell-mell in a cloud of dust.

The pilot was able to take off in the nick of time, just as the trucks loaded with soldiers arrived on the scene. I prayed the soldiers would not open fire and bring the plane down in an explosion of flames.

Once airborne, out of reach of gunfire and safely on our way to N’Djamena, my heart went from thumping wildly back down to normal. We radioed ahead so that the embassy folks could meet us at the airport and whisk us back to the compound.

After hearing the story, the ambassador was concerned that I, as a U.S. Foreign Service officer, had essentially lied to a high-level Chadian official. Nonetheless, we got the PCV on an Air France flight out of the country early that same evening.

I fully expected to be “PNGed”—expelled from the country by the host government, persona non grata—as soon as the next day. In the morning, I received the dreaded call from my friend, the presidential adviser at the palace.

“Pete, you have no idea what a beehive you kicked down there in Sarh,” he said. “It really caused a firestorm!”

I waited for the fateful words and began mentally preparing to pack my bags. Instead, he let out a loud laugh.

“Mon Dieu, c’est quelque chose que nous aimerions même faire! (My God, that’s something we would have liked to have done!),” he said and hung up the phone, still chuckling.

The African Affairs Bureau in the State Department (AF) was also concerned about the episode, at first. Eventually, though, the storm blew over. It was not the first time AF had encountered an unorthodox case in which an overly rigid adherence to rules and regulations might have played out in counterproductive fashion in the real world.

(Note: The bureau has a good reputation among “Africa hands” for being quite understanding about such things. The embassy country team, together with the Peace Corps director, also discussed ways in which Mission Chad might compensate the village for the loss of its chief.)

In the end, I was paid one of the best compliments I’d ever received. It was from Dorothy, the Peace Corps nurse from Cameroon, who said to me with a smile, “Eh bien, Monsieur Harding, vous êtes un vrai diplomate! (Well, Mr. Harding, you are a real diplomat!)”