A Victory Against McCarthy—The Bohlen Confirmation

Nominated as U.S. ambassador to Moscow by President Eisenhower, Charles E. Bohlen met resistance head-on from Republican senators during the Red Scare.

BY AVIS BOHLEN

A portrait of Charles E. Bohlen, circa 1951.

Ullstein Bild / Getty

When President Dwight D. Eisenhower took office on Jan. 20, 1953, Charles E. (Chip) Bohlen was at the peak of his Foreign Service career. Only George Kennan could rival his reputation as a Soviet expert. After interpreting for President Franklin D. Roosevelt at Tehran and Yalta, he had served with distinction under President Harry Truman, earning a promotion to counselor of the State Department in 1948 and participating actively in all major events of this seminal period, including the Marshall Plan, the Berlin blockade and the creation of NATO. Endowed with good looks, an easy sociability and an irreverent wit, Bohlen had a wide circle of friends in Washington and was popular with his colleagues and the press alike.

But as a charter member of what the Republican right was calling Truman’s “architects of disaster,” Bohlen expected little from the new Republican administration. He was surprised, therefore, when John Foster Dulles, the new Secretary of State, informed him on Jan. 23 that the president personally had chosen him to be U.S. ambassador to Moscow. Eisenhower in his memoirs judged Bohlen “one of the ablest foreign policy officers I had ever met.” The two men had known each other and played golf together in Paris when Eisenhower was supreme allied commander in Europe and Bohlen was minister in the Paris embassy.

Bohlen would certainly not have been Dulles’ first choice, however. Their close association at various international conferences during the early postwar years had bred a mutual antipathy. Put off by Dulles’ ponderous, moralizing anti-communism (a favorite phrase of Bohlen and his friends was “dull, duller, Dulles”), Bohlen never hesitated to disagree with him publicly.

He became even more critical when Dulles, shedding any pretense of bipartisanship, became a strident critic of Truman’s foreign policy after 1948 to curry favor with the Republican right wing. Dulles, for his part, openly admitted, as State Department security chief Scott McLeod recorded in his diary, that he personally disliked Bohlen for having “repeatedly undercut him” in the past and “did not consider [Bohlen] the type of individual who should be named ambassador to Russia.” But of necessity Dulles bowed to the president’s wishes.

Though naturally pleased, Bohlen accepted “with misgivings, given the political climate of the times,” he recalled. He worried that his long association with the Democrats, and in particular his role at Yalta, would prove a liability for the president, whom he deeply respected. He warned the Secretary that, if asked, he would give the version of what happened at Yalta, “which I knew to be correct and which would by no means tally with [that of] the Republican National Committee.” Dulles, slightly taken aback, suggested he downplay his role. Bohlen declined to come across as “the village idiot.”

Partisanship and Anti-Communist Hysteria

Bohlen’s fears were well founded. The Republicans had returned to power in a poisonous atmosphere of vicious partisanship and anti-communist hysteria. “A miasma of fear and suspicion infected America,” Bohlen would write. Senator Joseph McCarthy (R-Wis.) was at the height of his popularity and power, peddling to an anxious public a welter of false charges about communist spies in government, and enabled by a Republican Party that dared not criticize him. Multiple security investigations during the Truman administration had effectively rooted out any communist agents, but McCarthy’s witch hunts would continue unabated under Eisenhower.

In 1953 McLeod, a rabidly anti-communist former Senate staffer with close personal ties to McCarthy, had been named security chief at the State Department where, according to Dulles’ biographer Townsend Hoopes, he zealously pursued suspected “drunkards, homosexuals, incompetents or incompatibles” (real spies being in short supply). In a few short weeks, he fired several hundred Foreign Service officers.

Dulles personally reinforced his message: Assembling his senior officials on the front steps of the State Department in a chill January wind, he told them in “words as cold and raw as the weather,” Bohlen recalled, that the new administration expected not just their loyalty but “positive loyalty.” Morale in the State Department sank to a new low.

Bohlen’s nomination was forwarded to the Senate on Feb. 26, 1953. On March 2, he testified before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. The Republican senators—particularly Homer Ferguson of Michigan, whose campaign slogan had been “betrayal at Yalta”—pressed him hard on the wartime conference.

At stake now was not just Bohlen’s nomination, but also the president’s ability to run his own foreign policy and choose his own appointees.

Bohlen held his ground, however, giving detailed, factual answers and refusing to admit wrongdoing. The Yalta agreements had failed, he argued, because the Russians had not lived up to their commitments; moreover, the effort to cooperate with the Russians was a political necessity of wartime. After the hearing was over, Bohlen felt it had gone fairly well and didn’t “anticipate trouble.”

He was spectacularly wrong. His defense of Yalta, which made headlines the next day, came as an unwelcome surprise to the Republicans; overnight, his nomination became an issue. The big guns of the Republican right—Senators Styles Bridges of New Hampshire, William Knowland of California and, most ominously, Joseph McCarthy—came out in full revolt. Dulles was deluged with demands that the nomination be withdrawn.

Simultaneously, rumors began to circulate that derogatory information about Bohlen’s personal life had been found during his FBI background security check (astonishingly, the first of Bohlen’s career). Never a strong supporter of Bohlen, Dulles favored withdrawing the nomination. Eisenhower, however, as noted in the State Department’s Foreign Relations of the United States series, told Dulles firmly in a phone call that “he had not the slightest intention of withdrawing Bohlen’s name,” and instructed him to pass the message to Senate Majority Leader Robert Taft.

At stake now was not just Bohlen’s nomination, but also the president’s ability to run his own foreign policy and choose his own appointees. Meanwhile, a quick check with Bohlen’s Foreign Service colleagues put to rest any doubts about his moral character. Unsettling matters still further, the death of Joseph Stalin on March 5, 1953, was creating new uncertainty on the international scene and redoubled the urgency of getting Bohlen to Moscow as quickly as possible.

Bohlen, who was then inopportunely quarantined with German measles (“Lucky it wasn’t the red variety,” he quipped to friends and family), offered to withdraw. Dulles not only assured him of the president’s continued support, Bohlen recalled, but for reasons that would soon become clear, Dulles asked Bohlen to promise that “no matter what happened or might be revealed,” he would not quit and leave the president in the lurch. Bohlen gave his solemn word.

When, later that same day, Dulles read the summary of the completed FBI background check, he dismissed the personal allegations against Bohlen as “spotty and unsubstantiated” hearsay, according to Hoopes. (To give just one example of the flimsy charges used to destroy careers in the early 1950s: One openly gay source, who claimed to have an infallible sixth sense for spotting “queers,” is quoted in Bohlen’s FBI file as saying that he “walks, acts and talks like a homosexual” and believed him to be one.)

Charles Bohlen attended various international conferences, such as the Potsdam conference in Germany in July 1945. Left to right: Soviet leader Josef Stalin, Bohlen (interpreter for President Truman), V.N. Pavlov (interpreter for Stalin), President Harry S Truman, Soviet Ambassador Andrei Gromyko, Press Secretary Charles Ross, Secretary of State James Byrnes and Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov.

U.S. National Archives and Records Administration

Quid Pro Quo

On March 18, both Dulles and Bohlen were scheduled to testify before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. Dulles told Bohlen it would be better if they rode separately to Capitol Hill and were not photographed together. Bohlen, astonished and offended, wondered whether Dulles would have the guts to stand up to the senators. But, in fact, the Secretary of State gave strong and decisive support to the nomination. In a private meeting, he reassured the Republican senators that nothing in Bohlen’s FBI report put into question his loyalty to the United States or his personal character.

Before the full committee, Dulles lauded Bohlen’s qualifications and Soviet expertise, and emphasized the urgency of getting him to Moscow in this critical period after Stalin’s death. He reassured the doubters that the ambassadorship to Moscow was not a policymaking role. Bohlen then testified again, going over much the same ground, after which the committee voted 15–0 to send the nomination to the full Senate. The following day President Eisenhower gave Bohlen a ringing endorsement in a press conference.

Bohlen’s confirmation was henceforth assured, but not without several bumps along the way. Unlike Dulles, after reading Bohlen’s FBI file, Scott McLeod had concluded that he was a grave security risk. Miffed at being overruled by Dulles in his Senate testimony, McLeod, according to his diary, went over the Secretary’s head to complain to a top White House aide that Bohlen was “the keystone son of a bitch” of the Foreign Service, and the president should know he was a grave security risk.

Dulles and the White House were furious at this act of open insubordination, but after several frantic rounds of consultations, they decided, according to Hoopes, that firing McLeod would cause a “firestorm” on the right and was therefore too dangerous. But then the Dulles-McLeod dispute leaked to the press, leading to further uproar in the Senate.

By this time, McLeod was feeling somewhat abashed at the problems he was creating for the president and promised Dulles he would toe the line and support the president. Like some cloak-and-dagger spy drama, while Dulles publicly denied there was anything derogatory in Bohlen’s file, McLeod was spirited secretly out of the State Department with a staff member assigned to keep him out of reach of a subpoena from McCarthy, who was hot on his trail. He was kept overnight in an undisclosed location until he could be transported to his home in New Hampshire.

With the Senate in an uproar over his FBI file, Bohlen now found out why Dulles had extracted his solemn promise not to withdraw “no matter what happened”: His brother-in-law Charles Thayer, consul general in Munich, was about to be dismissed from the Foreign Service on the baseless charge—thrice disproven under Truman, but now revived—that he was, in the commonly used parlance, a “homosexual security risk.” Bohlen confronted Dulles, who confirmed that this was, indeed, why he had made Bohlen solemnly promise not to resign. Angry and disgusted, Bohlen agonized over whether to withdraw his name. But in the end, he felt bound by his promise to the president.

Cloak and Dagger

A Note on Sources

All quotations from Charles E. Bohlen are from his memoir, Witness to History, 1929-1969 (Norton, 1973), unless otherwise noted. Quotes from Charles Thayer are from his diary or letters, housed in the archives at the Harry S Truman Library and Museum. The material on Dulles can be found in The Devil and John Foster Dulles by Townsend Hoopes (Little, Brown, 1973). Quotations from Scott McLeod came from his diary, portions of which are in my possession.

—A.B.

By this time, Bohlen’s confirmation had become a national cause célèbre, with daily, largely favorable, press coverage and letters of support from all over. The final Senate debate on March 23, with the FBI file now a central issue, was “long, angry, sometimes eloquent, sometimes quite personal,” according to Hoopes, pitting Republican against Republican.

McCarthy, the loudest and most long-winded, infuriated Taft by implying Dulles had lied when asserting that there was nothing derogatory in Bohlen’s FBI file. McCarthy claimed, falsely, on the Senate floor, to have certain knowledge that there was something “so derogatory” in the file that “we cannot discuss it [here].” At the end of many hours of debate, Taft postponed further discussion.

Simultaneously, at the other end of town, Charlie Thayer, sitting incognito in Bohlen’s office at the State Department, was facing the unpleasant realization that his career was at an end. He had arrived secretly in the United States and made his way “as inconspicuously as possible” to the State Department, he recorded in his diary. It became clear that the State Department had withdrawn “its protection.” Fighting the charges would be futile, Bohlen said, since the president and Dulles were bent on “‘getting along’ with McCarthy.”

Thayer agreed to sign a letter of resignation, but then had to fight hard to exclude any mention of the unproven “morals charges” (i.e., homosexuality). As Thayer recalled, only when Bohlen “got mad, his hands and his face twitching with anger,” and threatened to withdraw his name did the State Department agree. All the while, the teletype in the next room continued to clatter out reports of the Senate debate on Bohlen. Bohlen’s wife, Avis, called to ask her husband if he knew where her brother, Charlie, was; Bohlen, sure his phone was bugged, lied that he had no idea.

That night, after seven hours in the United States, Thayer flew back to Munich in great secrecy “like a fugitive criminal.” He felt, he would write later in a letter to a friend, that he “was in a cross between a madhouse and a gangsters’ hideout. Everyone was looking over his shoulder, whispering, sighing and groaning as though the devil was about to get them.”

On March 24, Taft, after overnight consultations with the Foreign Relations Committee and the administration, proposed to the Senate that two senators, himself and Democratic Senator John Sparkman from Alabama, be authorized to read the file in Dulles’ office. The next day, they were able to report back to the full Senate that Bohlen was a “completely good security risk in every respect.” Though McCarthy and others continued to denounce the nomination, on March 25, 1953, the Senate voted to confirm Bohlen 74–13. When Dulles called Taft to thank him for his efforts, according to Hoopes, Taft replied curtly, “No more Bohlens.”

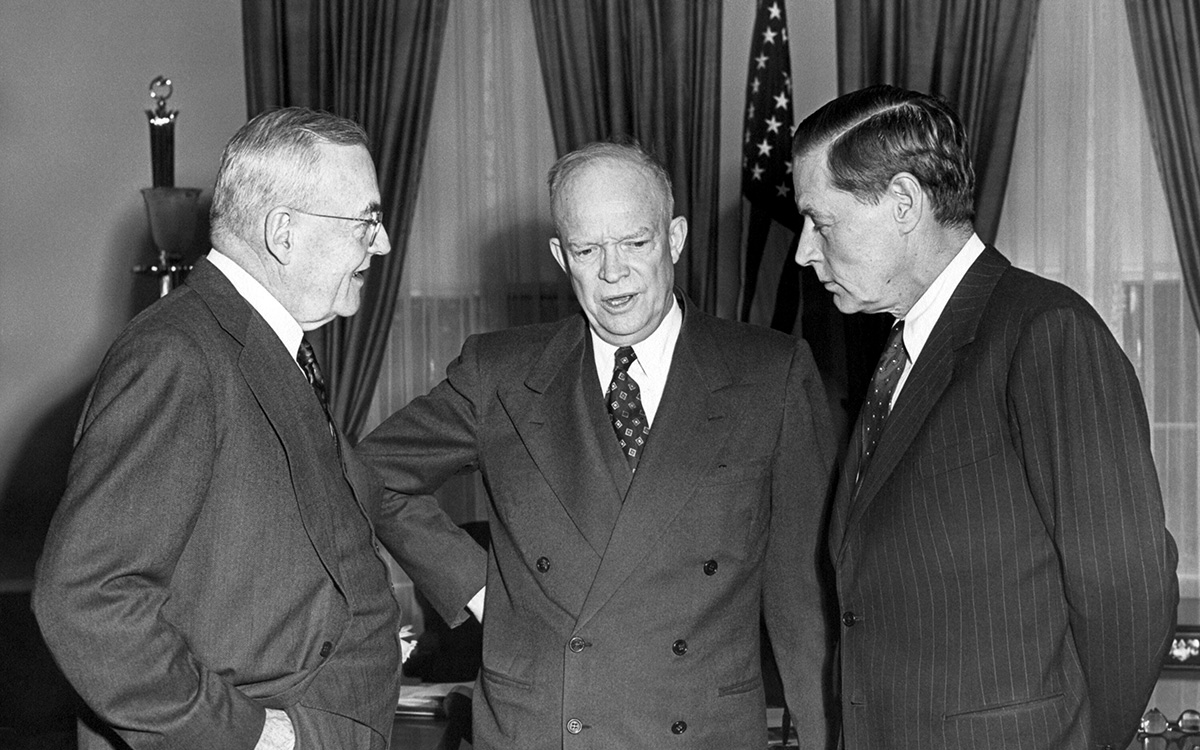

President Dwight D. Eisenhower in conversation with Secretary of State John Foster Dulles and Charles Bohlen, shortly after his confirmation, on April 2, 1953.

Everett Collection

Standing Up for State

“Hurray, huzzah and hosanna,” wrote one of Bohlen’s supporters. He was quietly elated: “I do not deny the feeling of triumph that possessed me,” Bohlen would write. He had not only “won the battle to occupy the position I trained for [for] nearly 25 years,” but also scored a victory for “the nonpolitical career Foreign Service [drawing] a line beyond which the witch hunters like McCarthy and McCarran could not pass.” This established “that Dulles and Eisenhower, not McCarthy or McLeod, would control State Department functions” and “preserved the President’s right to choose his representatives overseas.”

Bohlen would always be proud that his nomination, McCarthy’s first serious defeat, had played a role in stopping the demagogue. He himself had come through his ordeal with flying colors, winning high praise for his unwillingness to compromise his principles.

But the battle left many scars and was far from won. The Foreign Service continued to be ravaged by McLeod’s purges. During his farewell call on President Eisenhower, Bohlen, in his capacity as president of the American Foreign Service Association, described frankly the damage being done by the endless security checks and loyalty investigations, and the pervasive fear it had inspired in the State Department.

Eisenhower in effect shrugged, conceding Scott McLeod’s appointment had been a mistake, but he could not be removed “without a great big stink,” Bohlen recalled. Still less did Dulles, always afraid of angering the Republican right, stand up for the State Department or the Foreign Service. Bohlen’s confirmation was a setback for McCarthy, but more than a year would pass before the Senate summoned the courage to censure the senator from Wisconsin—demonstrating, not for the last time in American history, how a demagogue can manipulate a backlash from his loyal supporters to intimidate his party into silence.

Before his departure, Bohlen met with Dulles, who advised with his habitual tactlessness that it would be “wiser for you and your wife to travel together,” Bohlen recalled. Dumbfounded, he asked why. “Well,” Dulles replied, “you know there were rumors in some of your files about immoral behavior, and it would look better if your wife was with you.” Bohlen, outraged, replied frostily that he did not intend to change his plans.

Read More...

- “A Time of Great Malaise,” by Felicity Yost, The Foreign Service Journal, October 2020

- “The Exile of a China Hand: John Carter Vincent in Tangier,” by Gerald Loftus, The Foreign Service Journal, October 2020

- FSJ Special Collection on Loyalty Boards and McCarthyism